A month and a half ago, we asked you – our beloved readers – to send us your views and opinions about the internship issue.

An internship, in the architectural profession, is both an academic obligation as well as a professional precursor. Even more so, it is a rite of passage, the one shared experience that ties everyone together. A time fraught with uncertainty and self-doubt gives way to self-discovery and a renewal of one’s sense of purpose – a true metamorphosis that helps us find our place in the fraternity.

Of course, much like everything else that sounds so rosy, the reality of the situation is far from ideal.

The architectural workforce is ballooning; in the last 10 years alone, 297 new schools of architecture have come up in the country, with the CoA website boasting of about 531 institutions in total (their downloadable list shows 423 institutions). It is also worth noting that the intake of the newly minted schools far exceeds those of their predecessors – while the ‘old’ schools (commenced operating before 2006) have a total annual intake of about 8237 students, the new institutions alone have available seats numbering 15490.

This translates to nearly 3 times the number of students entering the workforce each year as compared to just 11 years ago – but has the market even expanded to this extent?

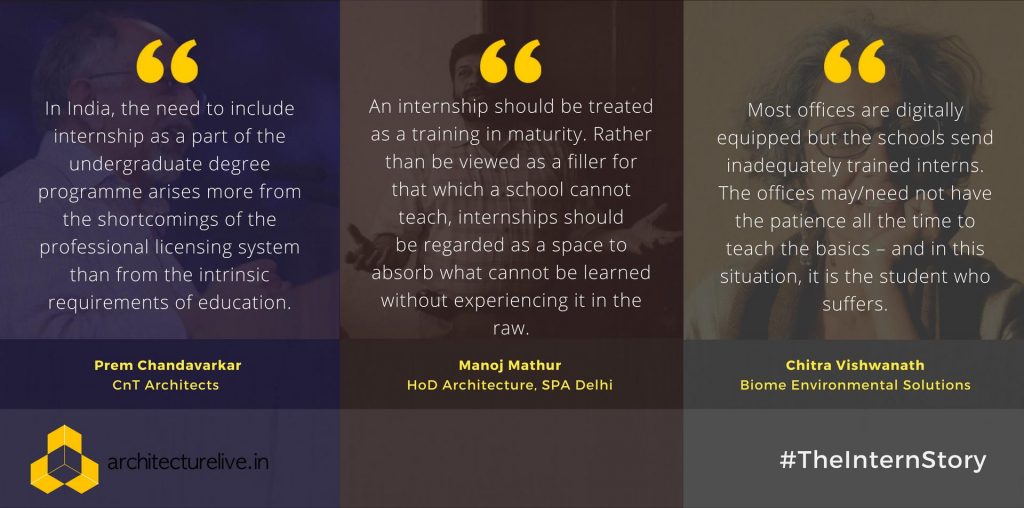

As Prof. Manoj Mathur points out, not every holder of a Bachelor’s degree in architecture will choose to practice in the conventional sense; even fewer will stay in the field a few years past graduation. However, as an internship is an academic requirement more than anything else, each of these 23,000-odd students need to – nay, are mandated to – acquire a spot in an internship program in one firm or another. It is important to note here that an Internship Program is a misnomer in most cases – very few firms, if any, have a cohesive agenda set down for initiation and training of the incumbent interns. While no firms are actually required to have such a well-defined program in place – especially since internships, largely, are an unregulated affair – it also translates to several thousands of students each year going to different cities and unfamiliar workplaces only to be disappointed at the lack of exposure given to them.

But of course, sub-par exposure and less-than-ideal internship scenarios will crop up no matter what the size of the student body or the intent of the firms – what stands out the most painfully in this situation is the fact that the students are left with little autonomy in terms of choice of workplace and discernment. Students – more often than not – have to accept whatever offer comes their way, and with it comes the issue of accepting the conditions of that offer.

A month and a half ago, when we asked you – our beloved readers – to send us your views and opinions about the internship issue, we were overwhelmed with your numerous and cogent responses. More so, we were disheartened to hear of so many accounts of disillusionment, dissatisfaction, and even exploitation.

From several eminent architects weighing in about how disappointed they are at the probable plagiarism and evident deception prevalent in the applications received during the time of selection to several reports by students about mistreatment and abuse at the hands of employers, there is little that hasn’t been discussed as part of The Intern Story. The underlying theme of it all is one of urgency – and may we say it – desperation. Knowing that an internship is necessary to validate five years of tuition, it is not surprising to see students resorting to unseemly tactics to secure an internship, neither is it surprising to see many firms tap into this urgency by hiring interns under sub-optimal conditions. The demand and supply imbalance – that has been the core of our premise from the very start – only makes it abundantly easier for unethical workplace practices to sprout, with little to no provisions for regulation or redress.

Is this where we wish to head as a professional community?

Of course, not everyone shares in this bleak outlook. Prof. Prasad Shetty and Prof. Rupali Gupte make an excellent point about how market forces tend to balance all discrepancies of demand and supply over time, and it is evident that an overabundance in the labour market will be met with diversification of occupation among graduates as well as a steering away from the course by prospective students. Similarly, Ar. Prem Chandavarkar notes that a degree in architecture does not equip one fully to practice right after graduation. Further, a degree in architecture does not limit one’s scope to the building industry alone; given its comprehensive nature and broad scope, architectural education – in fact – provides one a solid foundation to build a career in one of several allied fields. To regard a B. Arch as a pipeline process only serves to blindside the students.

However, until the situation stabilizes itself – whether through adjustments of the market or through diversification of trade – it is evident that we need to do something. Intervention is the need for the hour – but where does this intervention start?

Let us recapitulate the suggestions we have received, so far:

- A good place to start would be through asking what an internship really means – and whether the terminology even fits our requirements. As Prof. Tapan Chakravarty notes, we tend to use Internship, Training, and Apprenticeship interchangeably, which is symptomatic of – as well as contributes to – the lack of clarity on the issue. We cannot, as a professional community, reach a consensus about Internships unless we are on the same page regarding what the program actually entails.

- To question whether we need internships at all – especially in their existing iteration – would be the second step. As has been pointed out before, an architectural education alone does not fully equip one to practice. The delinking of education from licensing is an extremely important step that will help both curricular learning and on-field experience to play their parts in full. Mandatory internships are often used as a stand-in for actual professional experience to justify getting a license directly upon graduation, and need to be outmoded.

- While mandatory internships shouldn’t be the norm, voluntary internships should definitely be encouraged. Further, the primary objective of an internship should not be to produce work that can be used for evaluation by the school, but to gain exposure and experience; as such, internship should not be limited to traditional architectural firms alone, but include a wide variety of workplaces and organizations across various allied fields. This would reduce the burden on the existing firms to accommodate interns each year as well as allow students to diversify their skill-set and find their professional calling.

- Meanwhile, the firms that do provide internships must question their own approach towards it. As Ar. Samar Ramachandra elucidates, an internship must involve conscious mentorship as well as a constant exchange of ideas, and not just rely upon the intern being given instructions to complete tasks as necessary.

- Students must also take responsibility for honing their skills and ensure that they have value to offer to the firms that keep them. Ar Gita Balakrishnan and Ar. Vidhya Gopal provide excellent guidance and resources to help prospective interns put their best foot forward while looking for suitable opportunities.

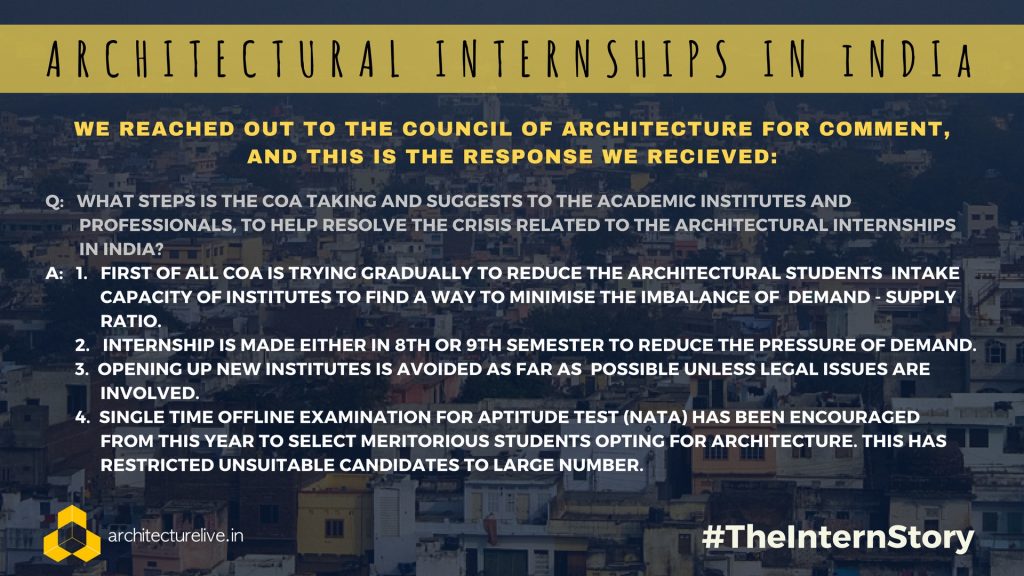

But none of these would work if we do not address the two core problems that have been pointed out time and again – irresponsibility of the Council, and apathy of the Institutions.

As irreverent as it sounds, the Council’s decision to grant affiliations to such a large amount of schools in such a small time-frame is the biggest culprit – inflating the pool of eligible candidates, lowering the quality of the talent, and causing wages to nosedive (especially for entry-level positions). Further still, it made firms even more wary of employing fresh graduates – given their purported lack of skills – lowering the ease of mobility among those who did manage to get jobs. This situation percolated down to internships as well, with many firms opting out of hosting interns due to their incumbent costs to the organization, and still others using interns as cheap labour or demanding ‘security deposits’ from them for securing a position. The damage caused will obviously take quite some time to remedy itself; in the interim, the students will continue to suffer the most.

The Council has also failed to provide a framework for ensuring ethical treatment of all employees – including, but not limited to, provisions regarding minimum remuneration – and also not provided a channel for lodging complaints against unethical treatment. Even though the statutory body is responsible for regulating both education and practice of the profession, their involvement in the task goes little beyond a few clauses in the Architects (Professional Conduct) Regulation. Even these, in fact, do not define any fixed parameters for control, or provide a pathway for restitution.

The institutions are equally responsible in this debacle. As stated before, internships are educational obligations. However, despite the student being enrolled at the time of training (and also being made to pay the fees for a full semester, as well as be mandated to bring back their work for academic evaluation), the institutions does little to ensure either the student’s preparedness for the process or the authenticity of his/her work. Further still, most tales of exploitation of interns are accompanied by the common refrain that their ‘institutions refused to get involved’. If, at this time, the Council doesn’t provide a platform for resolving issues nor do the institutions provide any support, what is a student to do?

At this juncture, many of you might notice that our stance is markedly pro-student, above all else. However, this is a conscious decision – we understand that a student of architecture is a newly-minted adult and unfamiliar to the field at large. They are in direst need of support and guidance, and are easily cowed into silence. This particular demographic, however, is the future – how we initiate them into the profession will have a tremendous impact on design, whether ideological, professional, or academic. These are our future theorists, practitioners, planners, administrators, teachers and consultants – how we nourish this crop has a direct bearing on the world we will one day open our eyes to.

If we do not take the necessary steps now – bringing the issue to light, creating room for discussion, brainstorming possible solutions, and campaigning for reform – then there is little hope for the profession at large.

We’ve done our part by grabbing your attention – what happens next?

You can access the preceding articles on the #TheInternStory here