The shiny, monolithic skyscrapers of Gurgaon cannot possibly look any more out of place than when viewed from the unique vantage point that Aya Nagar offers.

“For me, it has been a big learning experience to come and live in a slum. When I came here 15-16 years ago, it was a village of about 15,000 population which has grown into 1,50,000 in this time. And I point out to these people – my neighbours – that this city has been made by you. It’s outside of the jurisdiction and has been set up entirely by the people. You cut up the plots as you saw fit, made roads, and arranged for electricity… you can tell that our carbon footprint is about 1/50th of Gurgaon – you can see those office buildings from here, by the way – and the quality of life here isn’t bad; they have access to electronics and education and medical care… This is what people come to the city for – so that our children can get a better future.”

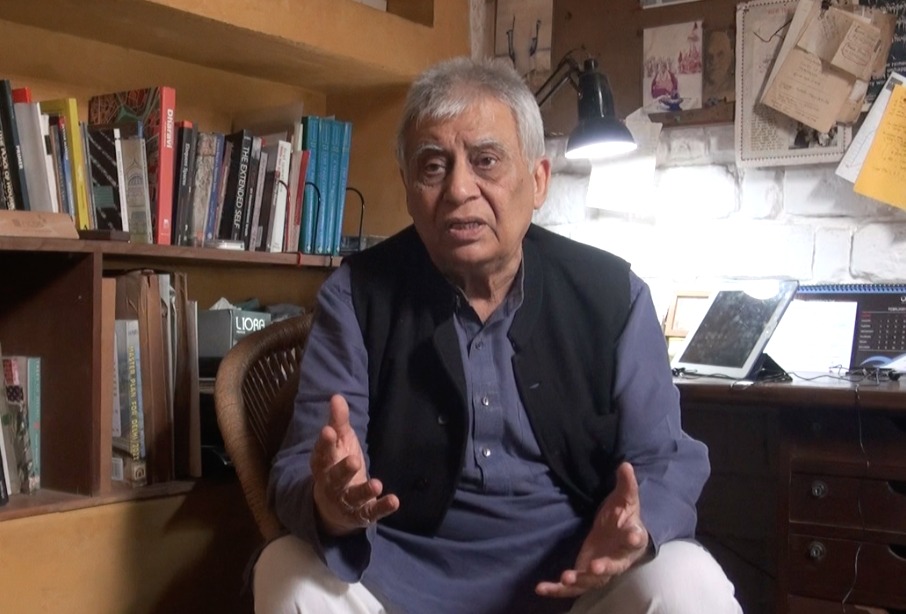

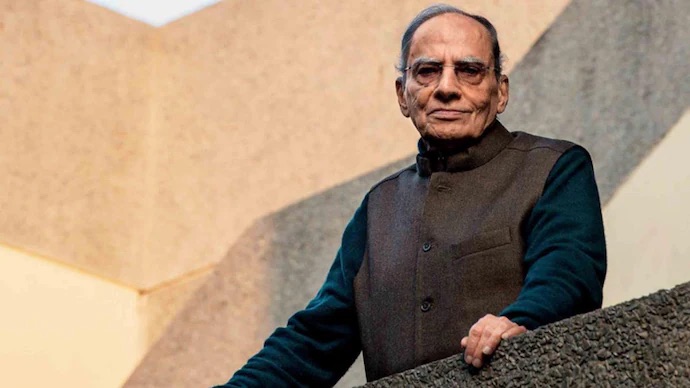

It is this statement – more than his impressive career and decades of academic research and community building initiatives – that reveals exactly how, and how well, Ar. M. N. Ashish Ganju understands the role of an architect in the society – one of an educator and an enabler; a part he has been playing as he works hand in hand – quite literally, in fact – with the residents of this area, most of whom come from economically and socially marginalized sections of the society.

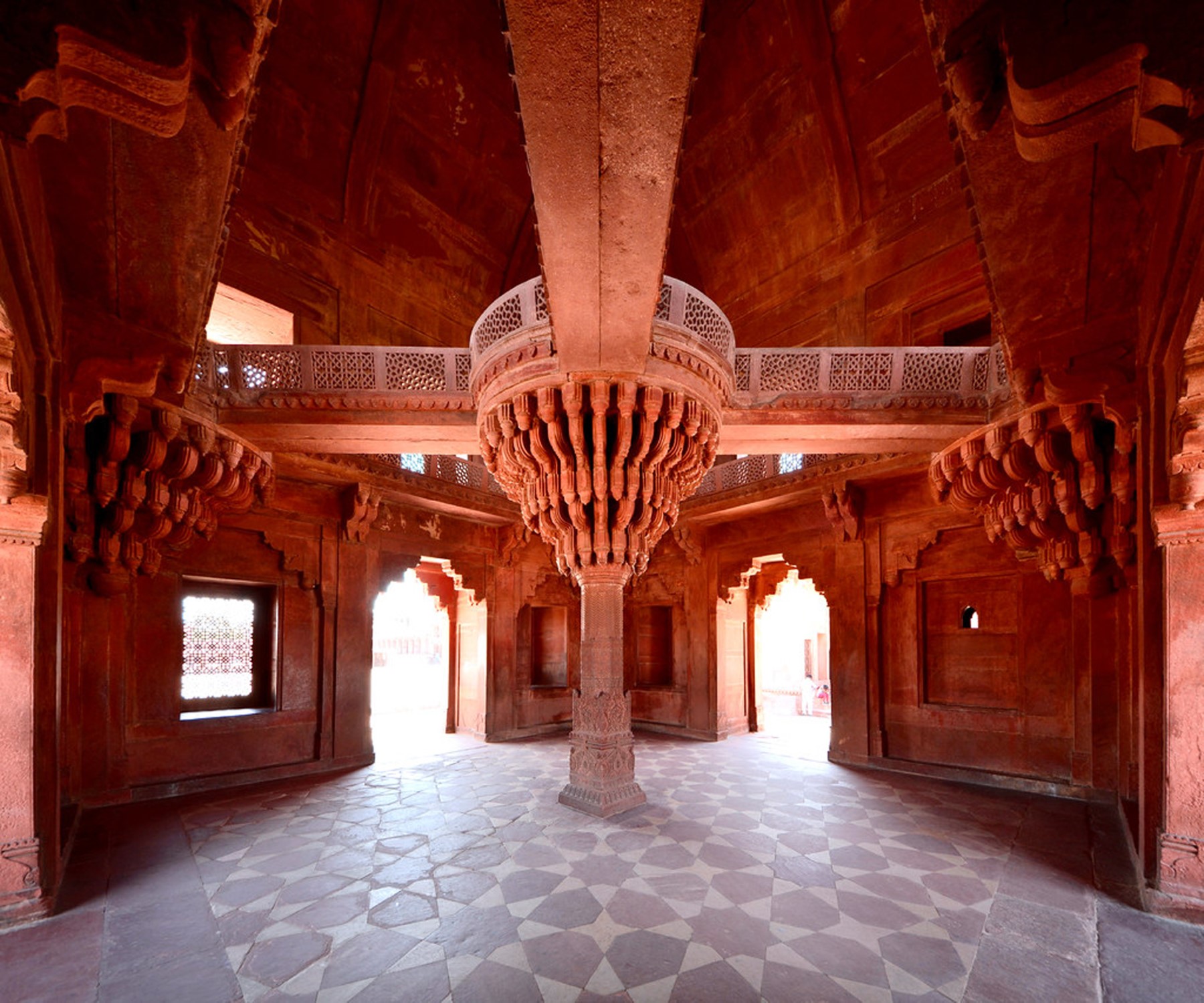

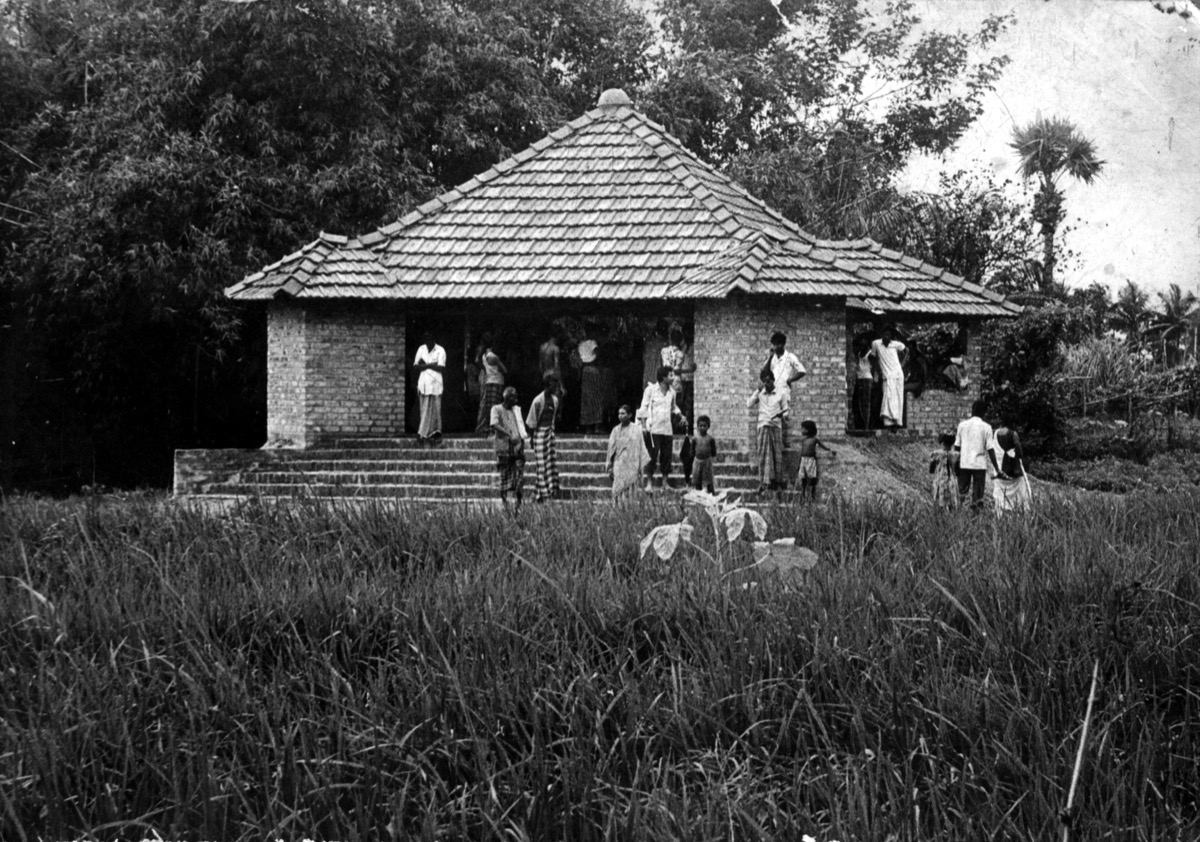

We have discussed at length the disconnect between the architectural community and the general society in the past few weeks – discussing the impact of polity and economy, the role of academia in dissemination of the right values, and the self-propagation of the practice – but Ar. Ganju emphasizes instead on how architecture needs to be inherently decentralized instead for it to reclaim its importance in the social sphere – empowering the people to create their own communities is the best tool we have of establishing and retaining our cultural relevance. “When I came back after studying abroad, I taught in SPA. I was aware of the fact that 80% of the population lived in the rural areas, but nobody in the college knew what we dealt with in these areas, or what these areas were, at all… I could not understand how we could practice architecture when it could not connect to the people… The bulk of architecture is based on a hands-on approach. We are one and a quarter billion, and everyone is busy building something – and they’re not going to the formal sector, it’s being done by hand… I teach a lot, and not just people in the profession. Over the years I’ve been working with the public – like small communities and refugees such as the ones in Dharamshala – and I’ve been teaching them how to build. In Dharamshala, they built a nunnery of over 100000 sq. feet without contractors, and it’s a dry space. And they’re very happy with it.” he says, referring to the Dolma Ling Nunnery and Institute in Sidhpur, Himachal Pradesh.

His aspirations are backed by solid action not just on an individual level but on a more broad-based, fraternal level, especially through his work with and through Greha, a society of architects – of which he is a founding member – who have been working towards overcoming the aforementioned disconnect by culling through architectural discourse tailored to our nation’s unique context – in addition to their work in Aya Nagar – through Architecture Collegium, a forum which fosters intellectual awareness within the profession, and through their discussion series ‘Architecture and Society’, which attempts to make this academic discourse accessible to the public by engaging directly with them,

“I think this distance of the architectural profession from the public is a major issue. Eight years ago, Greha started this group, where we sit together and debate how we can become more relevant to the society and reach out to the public… We came to the conclusion that architects were only talking among themselves, and that was taking us nowhere. So we spoke to the IHC administration and got their permission to run this program every month. We’ve had 13 talks in that series; we started in July of 2015… We have general public coming in these events. Next month we are having a panel discussion on Mehrauli and Urban Renewal – we’re trying to show that as architects we can work with people. People want their environment to grow – which is where we come in and help them work towards tangible change.”

However, this methodology of working on the ground beside the common man is at odds with the aspirational ideas that most young architects harbour these days – ambitions that invariably involve corporate comfort and financial gain. Ar. Ganju is firm about how these two motives should not be at the forefront of an architect’s mind for him or her to make a meaningful contribution to the profession and the society at large “I made it my primary interest to use my practice – because it’s not an office really – for primarily helping other people. And I’ve noticed that unless you chose helping others over yourself, you cannot grow. I feel this is how self-proliferation works; my office shouldn’t have worked, logically, but it did grow and it did expand… Architects are very fundamental to our living, especially to urban living. However, our education pattern is at variance with our ground reality, therefore the kind of architects we are producing are becoming fodder to these multinational realtors, which produce multi-storey towers and are one of the largest contributors to adverse climate change. These buildings are spoiling the climate – but for many new architects this is the ideal, because their focus is now only a good income. People are learning to earn – but at what price? What I see in all our cities is a proliferation of towers, which is an unsustainable pattern which adds to adverse climate change. And we haven’t produced any other model that we can aspire to. We need more students, but they must be serious architects, not just people who are interested in making profits. Because while earning is important, it should not be at the cost of the ecosystem.”

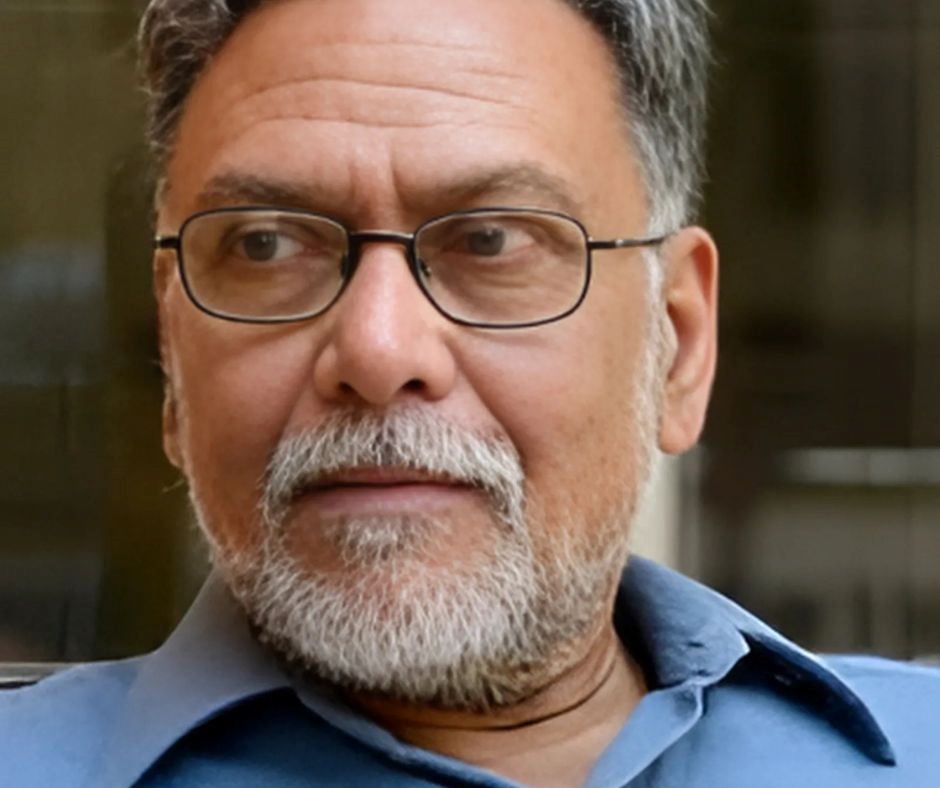

His concerns about how architectural education has failed to instil the right mind-set in young professional resonates in Prof. Nalini’s Mathur’s statement – and it is clear that this alienation of the academia from the ground reality is a major contributor to the disengagement between the society and the architect. He talks about how our primary aim – as a step towards the proliferation of the community as well as a social goal – should be towards creating better urban ecosystems, the poor understanding of which is what is causing the disintegration of our cities. “When we say F.A.R., we have no idea of how that correlates to the congestion in the city. In town planning, there is no mention of public areas; we have built up areas for various uses and private ownership, but the byelaws only go upto the plot boundary. There is no control and regulation beyond the plot boundary, so we have no tool to measure public spaces and areas in the city. As a result the cities are hopelessly congested, and yet we are talking about increasing F.A.R. based on patterns followed by other cities of the world.”

“No building stands alone – every building is part of a neighbourhood, and these neighbourhoods constitute an urban reality. And yet there are no modern urban theories and planning models that are tailored to our needs, because our condition is unprecedented in human history – never before have people moved into towns at such a high rate. And despite all the smart facilities and technological advancement, the city comes to a standstill within 10 minutes during rains. Our urban population is increasing by 4% per annum, and the rate of growth of slums is at 8-10% per annum. As the city grows larger, our slums grow larger too, and more and more area is occupied by them. We don’t know how these slums operate and or how they sustain themselves – the morphology of slums is unknown to us.” he adds, emphasizing the need for the profession to cater especially to the urban masses which lack the means to access our services.

“I believe that architects are people of learning first and people of commerce second. We used to be the learned men and women, so people would come to us for our counsel, and then offer us remuneration when they were content with the counsel,” he muses,

“The biggest problems architects face these days is that people don’t recognize us anymore and we are only needed for creating drawings at most. So unless we come to that position where we can demonstrate to the public that we are beneficial to the society, we will become increasingly irrelevant.” – M.N. Ashish Ganju

Perhaps, if we were to return to our roles as humanists, the society might yet find a place for us after all.