Anyone who does not attempt to change the future will stay a captive of the past.

Sheikh Mohammed al-Maktoum, Ruler of Dubai

As the host of the FIFA World Cup, Qatar continues to grab the globe’s attention; the country has heavily invested in its infrastructure to accommodate what is arguably the most followed tournament globally. In a show of massive infrastructure, Qatar is trying to outdo its neighbour, Dubai, that in turn, tries to outdo the biggest and the best in the world in a massive display of urban eye candy. But there is a dark side. The Dubai Dream, by H Masud Taj, introduces us to this dark side.

As a student of architecture, I took a break from my studies in India to work in a furniture factory in Sharjah/Dubai. A decade later I returned to Dubai as an architect in 1988 and again in 2008 to write on Dubai for an edition on Future Cities (arguably the earliest published essay that was sceptical of Dubai’s boom).

H Masud Taj

The following essay was previously published in Civil Society’s 5th Anniversary Issue on Future Cities Sept-Oct 2008, p.31-32 and is being republished after due permission from the author.

The Dubai Dream, by H Masud Taj

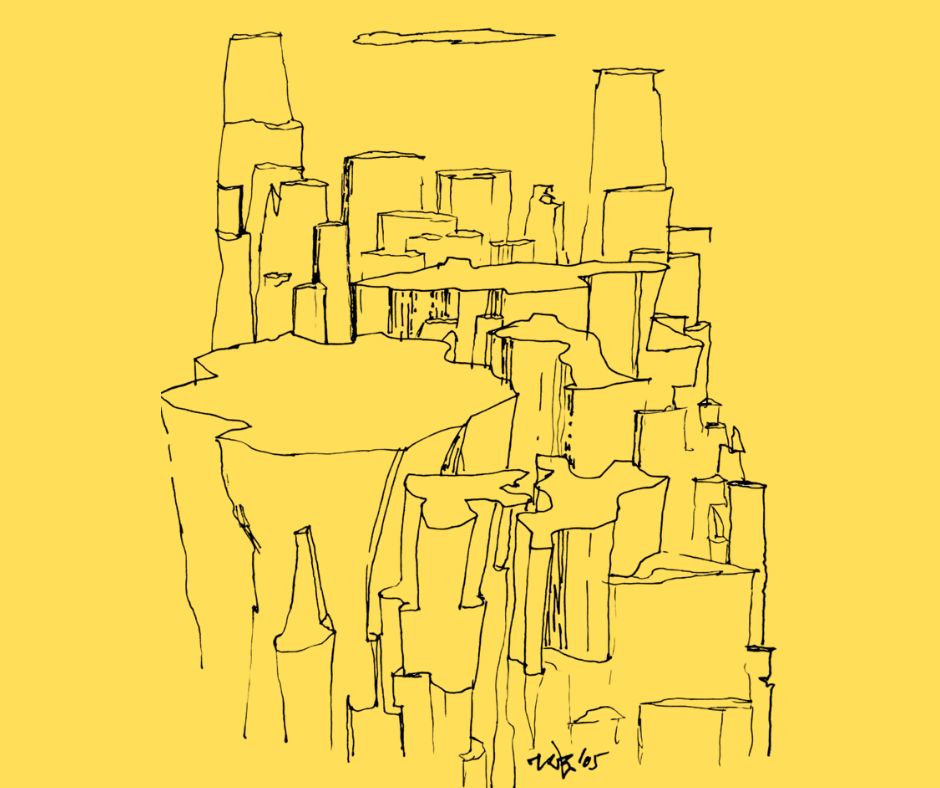

The president of the International Advertising Association, Joseph Ghossoub, missed the point when he recently said that the real estate adverts in Dubai are mediocre because images of the project dominate the company’s brand. In Dubai, the project is the brand. In SimCity as in Google Earth, you fly in from aerial views of the city you build. Dubai is playing clicks with bricks, their spectacular projects that brand Dubai can only be read while flying into the city – giant Palm Trees, Map of the World, Falcons. By 2010 they are slated to attract 15 million visitors to the city (Emirates Airlines has accordingly become the biggest purchaser of aircrafts in the world – $37 billion worth of Boeings and Airbuses).

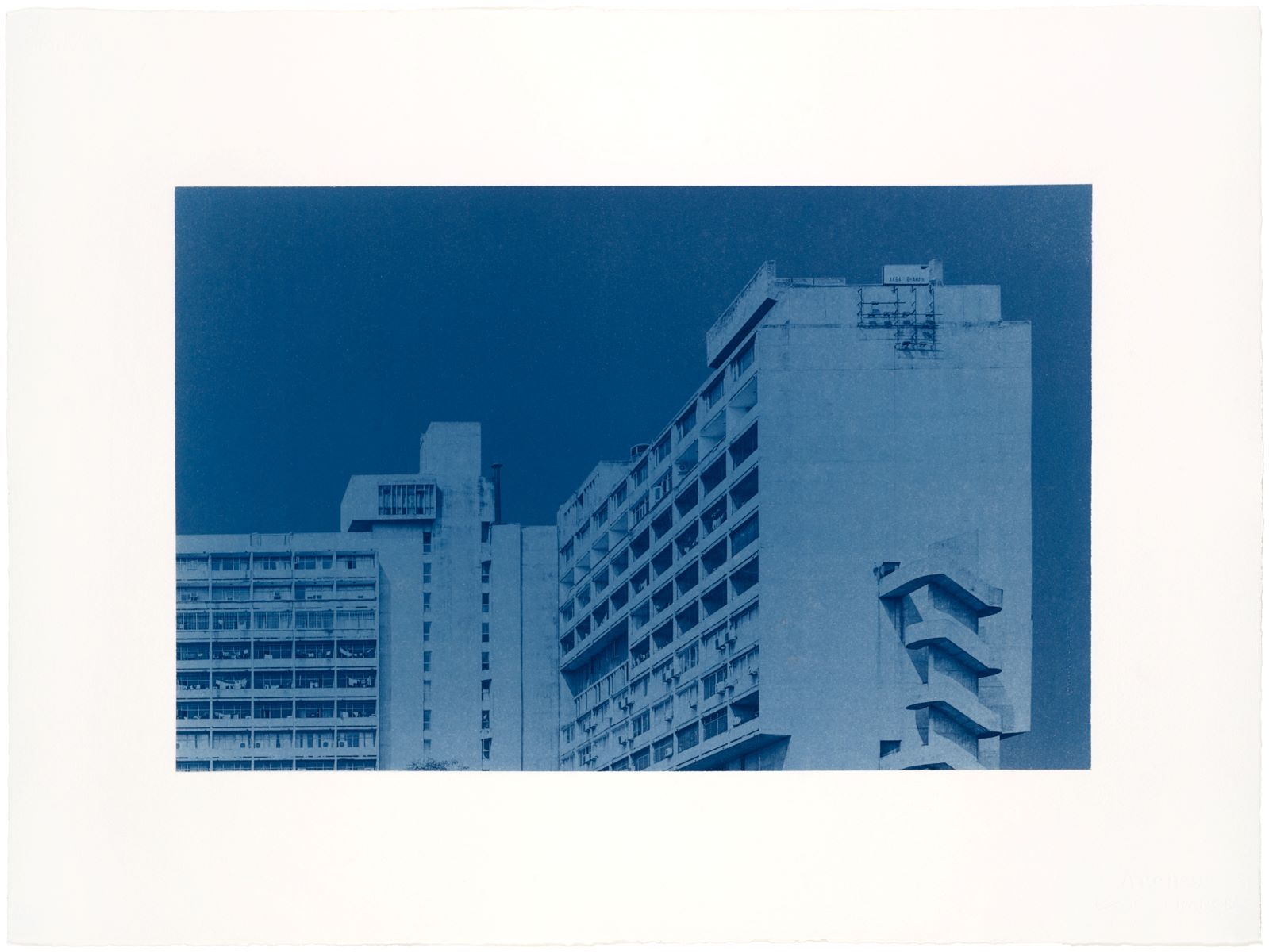

If developers could envisage a dream city it would be Dubai (native population of 1.5 million), the second largest construction site in the world after Shangai (pop. 15 million). When developers turn into planners, the market (whether existing or envisaged) determines the scale of operations and profit becomes the prime motive. But what developers primarily sell is not buildings but planning itself.

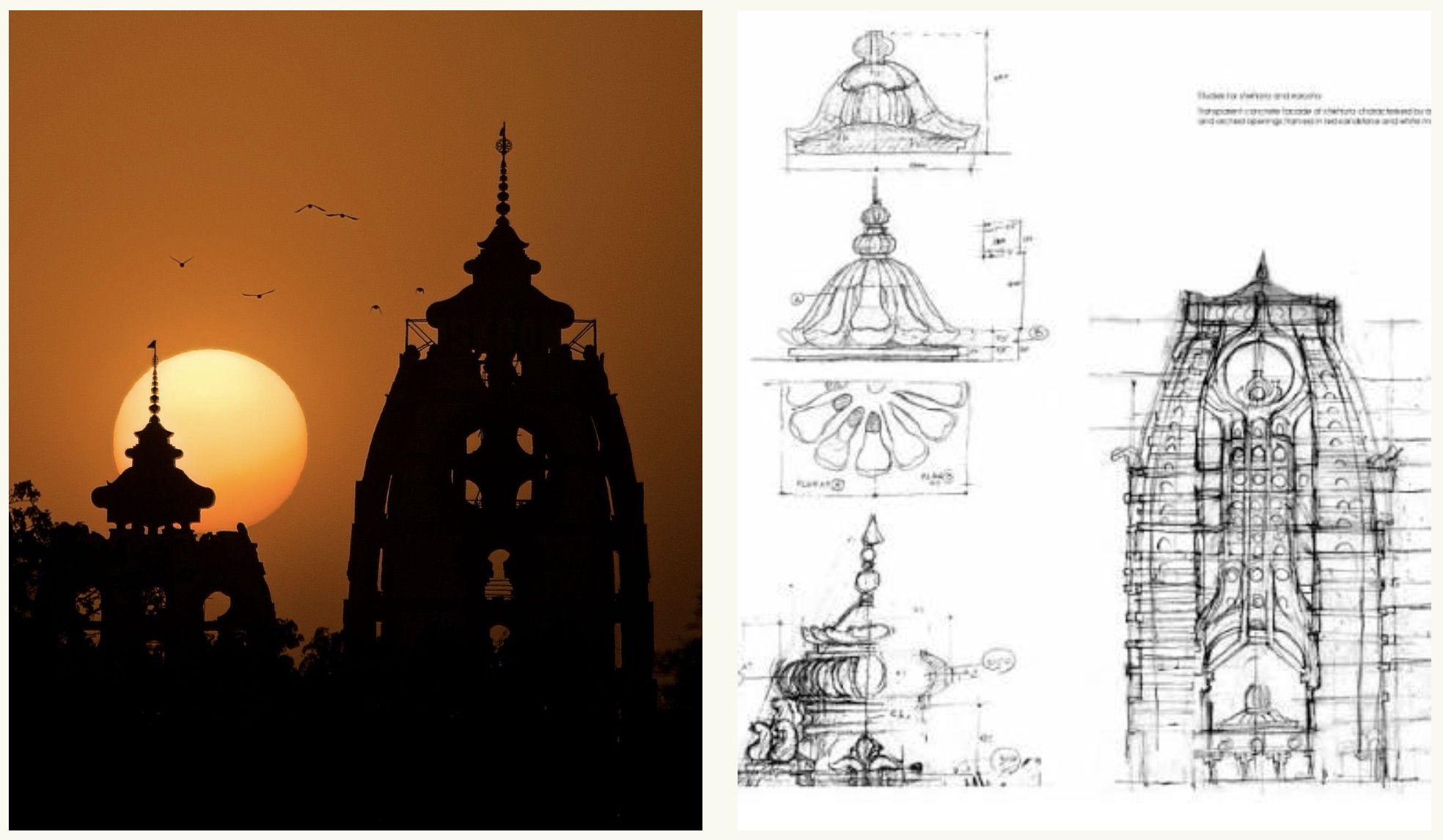

They (developers) sell dreams of a good life, the stuff of their adverts. Thus Dubai’s constitution is the Guinness Book of World Records as it builds the largest theme park in the world double the size of Disneyland, throwing in the Pyramids of Egypt, an Eiffel tower that is taller than the original tower, the Taj Mahal that is one-and-a-half times bigger, and the Leaning Tower of Pisa that duplicates the defect.

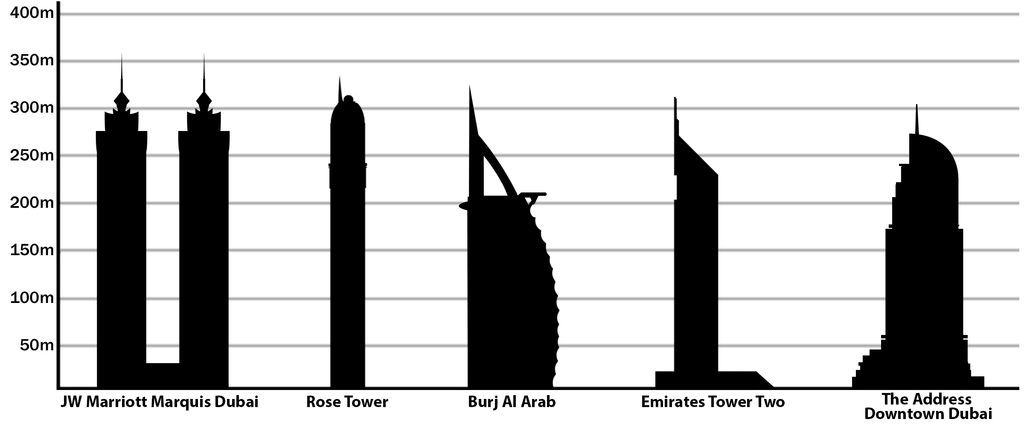

Also, the biggest mall in the world containing the largest aquarium in the world, the tallest building in the world, the tallest hotel in the world, the largest international airport in the world, the biggest artificial island in the world with the longest artificial beachfront in the world (1500 kilometres as against its natural 45 km beach), the first underwater hotel in the world. One in every five cranes in the world is swinging in Dubai, dubbed by the BBC as the world’s fastest-growing urban area.

When I first visited Dubai as a student in 1978 its downtown was Bur Dubai. The discussion then was that Dubai was foolhardy in making the largest man-made port in the world. But Jebel Ali opened as a free trade zone that proved all the sceptics wrong and became a precursor to its present urban strategy. Dubai now owns over 50 terminals in Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Australia apart from UAE. Thus the city is a node of a far-flung trade empire in the making. For instance, it is poised to rule the Indian container industry owning three major container terminals: Nhava Sheva, Mumbai; Chennai Container Terminal, Chennai; and Mundra International Container Terminal, Gujarat; along with the development of Vallarpadam Container Terminal in Kochi and a share in the Vishaka Container Terminal at Vishakapatnam. Dubai is also USA Navy’s busiest foreign port of call but UAE’s Minister of Information, Sheikh ‘Abdullah bin Zayid Al Nahyan does not shy away from asserting “The United States, which issues an annual list of states it labels as supporters of terrorism, must not forget to classify itself at the forefront of these states along with Israel”.

In 1988 I visited Dubai as an architect and saw its first office hi-rise Dubai World Trade Centre. Since 1998 that lone tower has been engulfed by a spate of tall buildings on the new downtown along Sheikh Zayed Road (named after the late Shaikh Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, recognized nabati poet and the founder president of UAE). This summer I saw Dubai’s 15 storeys Arc de Triomphe framing the World Trade Centre, the inhabited gate serving as a portal to Dubai International Financial Centre (DIFC), a stock market headquarters meant to match those of Hong Kong, London and New York. The other two sprawling industrial parks that followed Jebel Ali’s success are the Internet City to make Dubai the Arab world’s IT hub and Media City which seeks to replace Cairo as the Middle East’s media capital. A gated community space is political. The spatial distribution of Dubai’s enclaves is strategic; each catering to the thematic needs of its expatriate population and expatriate capital. Thus Media city has minimal press censorship, unlike elsewhere in Dubai, and internet access is unregulated in Internet City. DIFC with its Swiss-like financial secrecy and efficiency attracts money laundering by militants which paradoxically ensures Dubai from becoming a target of terrorism. (Little wonder that the doyen of Indian gangsters Dawood Ibrahim shifted his D-Company to Dubai, to operate from and not on, before himself moving on to Karachi).

The Financial Centre asserts its centrality with the tallest building in the world – the Burg Dubai, making history at the rate of one floor in three days, racing to double the height of its iconic structural predecessor: Sears Towers. The tallest building in the world shows no sign of halting. You cannot miss it on arriving on an early morning flight, but you will miss it during the day as the city gets engulfed in a haze of sand. The lean tower reappears as a fluorescent-lit apparition reaching impossibly high into the night sky. Pre-sales of its apartments command the highest price in the world at US$3540 per square foot. When the developer dreams up the city, irrational exuberance is the norm.

Swirling around this act of will on a former military base is the rest of the 20 billion dollar project (equivalent to UAE’s annual income) of its developer Emaar. The new Burj Dubai Downtown seeks to single-handedly shift the action away from Sheikh Zayed Road and anchor it to the downtown of the globe. With an artificial island in an artificial lake and an artificial Old Town, the biggest mall in the world (12 million square feet) with 16000 underground car parking, 30000 homes, 55 residential towers, 9 hotels and 6 acres of parkland. Mohamed Ali Alabbar is both the Chairman of Emaar properties as well as the Director General of Dubai Economic Development. The state controls 51% of Emaar shares and the private-public collaboration is reflected in Alabbar’s close relationship with Sheikh al-Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai. There is no conflict of interest because all land belongs to the Maktoum dynasty, and the only interest that prevails is al-Maktoum’s, CEO of Dubai Inc. In this state of breathtaking feudalism, with a single landlord, taxes can be minimal as the single beneficiary is the ultimate recipient of all rents and leases. The Sheikh owns the sand. In Dubai, it is the body of the land, and not what is beneath it that is traded.

The trade impulse extends to bodies as well. If on the macro scale Dubai works on the body of the land, selling and manipulating infrastructure, then at a micro level it sells the body of the prostitute. It is now an established centre of sex tourism with a choice of all manners of sex workers, Chinese, Russian, Armenian, Indian and Iranian including gay bars and nightclubs. And with hookers come the attendant hawkers and the hawks, the transnational gangs of the red-light industry. If sex sells then you rope in sex symbols for tough sales. Dubai’s inhabitants generate one of the world’s highest amounts of waste, and the city is among the toppers in energy consumption. Hence to counteract, neighbouring Abu Dhabi has roped in celebrity sex symbol Pamela Anderson to be the hotelier of an eco-friendly hotel: “It’s built with no fossil fuel at all in Abu Dhabi where they have all that oil” she said. It was emulating Dubai in which Pam’s counterpart the male-sex symbol Brad Pitt (“…architecture is my passion.”) was appointed as the “design consultant” by Zabeel Properties to design a multi-million dollar environmentally friendly hotel development. Reality is as real as publicity. Hence the tallest building in the world Burj Dubai was not based on the 6-pointed desert flower that its website claims and the tallest hotel in the world Burj Al-Arab does not have a 7-star rating, they were only convincingly marketed as such.

Little wonder in the game of fabricating fantasies, only Dubai can beat Dubai. Nakheel Properties has announced a 4000 feet high hi-rise- The Burj, to out-Burj Burj Dubai. Is that an empty boast? Not really, as a hoarding on one of their current projects (designed by Rem Koolhaas, a cool surfer of capitalist enterprises,) asserts that it is, quite simply, twice the size of Hong Kong. Having gone horizontal with the largest man-made islands in the world (Palm Tree and World Map in the ocean: “Where the Vision of Dubai gets built”) they aspire for the mother-of-all verticals.

Trade has always been Dubai’s forte. Though bolstered by federal oil, Dubai’s growth is founded on its historical ties with South Asia. Little wonder that half the UAE population is South Asian. The South Asian presence predates oil, and even during the colonial era the Gulf region was administered by the British Raj from Bombay. It is this legacy of trade (and gold smuggling) that is the predecessor of Dubai’s sans-oil success in the global market (the non-oil share of GDP is over 94%). Post-Khomeini, it attracted Iranian investors and experts and post-911, Saudi money flowed into Dubai and away from the USA.

The Maktoum dynasty is aware that Dubai Inc.’s success is premised on cheap oil, cheap sand and cheap labour. But chiefly it is premised on investor confidence that the gated city is indeed the capitalist safe haven.

But while oil and sand are mute, labour’s muteness has to be enforced. Thus the exotic orient has an unattractive underbelly of unjust labour laws that apply to temporary labourers from India, Pakistan and Bangladesh that do all the heavy work (12 hours a day and a minimum of 6 days a week in blistering heat).

Recruitment agents confiscate their passports and their rights disappear. Although Article 63 of the 1980 UAE Labour Law explicitly requires the Ministry of Labour to institute a minimum wage, it has never been put into practice. The same law also does not recognize the right of workers to organize and form trade unions. It also forbids strikes. But they have begun to strike. Several thousand in 2004, seven thousand for three hours in 2005 (the largest protest in Dubai’s history) and in 2006 two and half thousand went on a rampage at the Burj Dubai over pay and conditions.

Ironically for all the frenetic activity, celebrity designers and star architects, Dubai is a culmination of a dated city model of the 20th century and not the emerging prototype of the 21st. Its car-dependent form of urban sprawl belongs to the 70s America (though it is introducing the monorail) and the scale of spectacle and energy consumption is of 90s Las Vegas, which it has long since surpassed. For all its faith in consumerism and tourism and its single-minded synthesis of entertainment, shopping and architectural spectacle, for all its frenetic construction activity, it has yet to break fresh ground. Meanwhile, the tallest building in the world- the declaration of Dubai’s arrival in the global arena, continues to grow. Burj Dubai’s website boasts that the tower weighs as much as 100,000 elephants. Whether they are white elephants, only time will tell.

Image Credits

[1] imran shahabuddin, CC BY 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

[2] Ali Zifan, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons