My great great grandfather & Lord Byron’s granddaughter

H Masud Taj

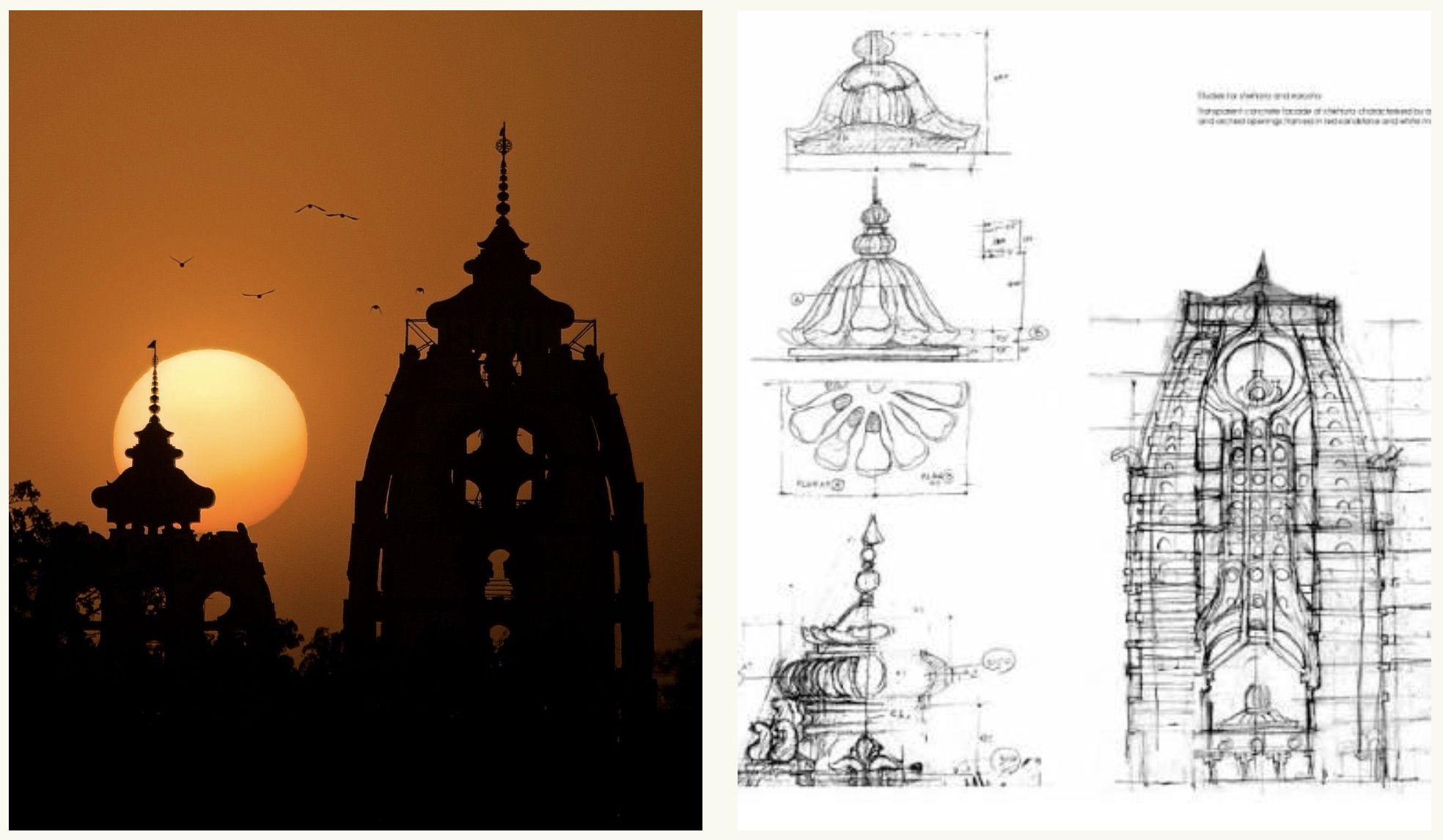

Moradabad, established in 1625 AD, was named after Prince Murad, the son of Shah Jahan, and became the most important city in that area. Eleven years later at the orders of Shah Jahan, on a high mound in the city, overlooking Ramganga, a grand tributary of the river Ganges, was founded the main congregation Mosque of Moradabad.

Adjacent to the commanding mosque, before the hillock’s descent, was the sprawling house of my grandfather, Nawab Ahmad Shuja-ud-Din Farooqui. As was the custom, my mother had come to the house of her parents for the birth of her child. In the bedroom that flanked the wall of the grand mosque, I was born. The house no longer exists, as it was engulfed by the ever-expanding mosque.

My mother had no memory of her father as he died when she was very young. From the library in the house, she knew he was a lover of books. His grandfather was the Nawab that had ruled Moradabad.

The cool marble floor of the adjacent mosque was my playground. The mosque had a still pool of water for ablutions that, for a toddler, extended forever. In it, there were aquatic plants and goldfish. From the ramparts of the giant mosque, I could gaze at the gigantic Ramganga. A wide-eyed growing child could not ask for anything more.

My grandmother’s house, spread out on different levels as the hillside topography lent itself, had a central courtyard in which there was a multipurpose platform open to the sky and a well with a hand pump. If you worked the cast iron lever handle, sparking water gushed forth in abundance splashing sonorously on levelled rock, splintering sunshine. The house was so large that once my father, on a surprise visit from Bombay, had to spend the chilly night huddled in the entrance verandah because all his thumping at the door and calls could not be heard by anyone asleep inside.

This sprawling house was small, my mother told me, compared to their previous house in which she was born, also in Moradabad. Her palatial mansion had so many doors that the last thing she recalls each night as a child was to spend a good half hour accompanying the maid with a ring of large keys, as they went from door to door, padlocking each in a jingling nightly ritual. The family had to move out of the monumental house as their fortune was on a downward spiral ever since her great grandfather, Nawab Majeed Uddin Ahmad Khan, affectionately called Nawab Majju Khan, was tortured and killed by the British.

The Great Uprising of 1857 was deemed a Muslim conspiracy by British military commander James Outram. It created fear in the imperial mind, hence Muslims faced the brunt of the British ferocious response that included blowing men with canons. The rebels, both Muslims and Hindus, chose the titular Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah, as their leader. The whole population of Delhi was driven out by the British, and thousands were killed after perfunctory trials or no trials at all. In Moradabad, north of Delhi, without trial, Nawab Majju Khan was killed on April 25, 1858. His estate was usurped, his sons imprisoned and his family left to fend for themselves. His palatial house was encroached on and dismantled. A crossroad in Moradabad still remains named in his memory: Shaheed Aazam Majeed-Uddin urf Nawab Majju Khan Chowk.

Growing up as a child, I didn’t know what to make of this story. No one mentioned the incident except my mother and her tales of torture involved elephants! Perhaps the fertile imagination of a princess deprived? The last I heard of it was in grade six as after that I chose to leave home to study in a boarding school in the hill station of Panchgani.

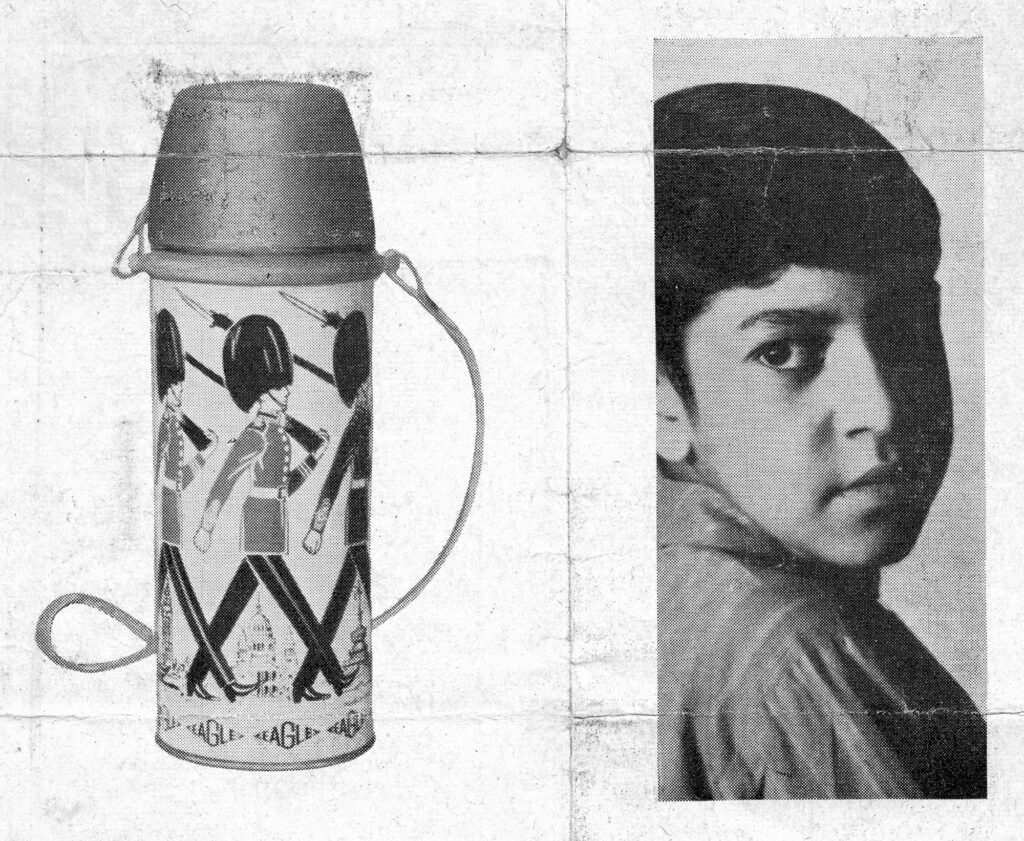

By high school, I was in Ooty, in the mountains of Southern India, far from home when, at age 13, my design appeared on Eagle Flask. My mother’s story had not dented a growing child’s fascination with the Queen’s ceremonial Foot Guards in their characteristic red tunics and bearskin hats, marching around a vacuum flask manufactured and sold in India, twenty-two years after the nation’s independence from the Empire. With imperial monuments in between their striding legs, the proto-architect was perhaps beginning to suspect the relationship of architecture to the pyramid of power, even while he and his fellow citizens remained insufficiently decolonized.

In my early 40s, I migrated to Canada but the Queen was the reason why I delayed, by several years, becoming a Canadian even when I had completed all formalities of residency. I had come to Canada to be a Canadian but the Oath Ceremony insisted I be a monarchist; a citizen who is also subject to an unelected, unaccountable, non-resident ruler. I did so when I realized it was less a personal allegiance and more an acceptance of the Canadian version of democracy and as a Canadian citizen, I would have the right to disown monarchism while continuing as a law-abiding Canadian. So it came to pass.

As a good Canadian, I have even protected the privacy of Queen Elizabeth II. The Foreign Affairs commissioned me to write a poem, render it in my calligraphy and design its permanent installation in India, the country of my birth. The Contract was between “Her Majesty the Queen in right of Canada (referred to herein as “Her Majesty”)” and I “(referred to herein as the “Contractor”).” Among the 35.1 clauses was one on “Confidential Information” which made me pause: “Any information of a character confidential to the affairs of Her Majesty [i.e. she] to which the Contractor [i.e. me]… becomes privy as a result of the Work to be performed under this Contract, shall be treated as confidential…” In other words, I was the Queen’s Accidental Confidant! All I can share is the book that resulted: Embassy of Liminal Spaces (freely accessible on Academia; your tax dollars at work).

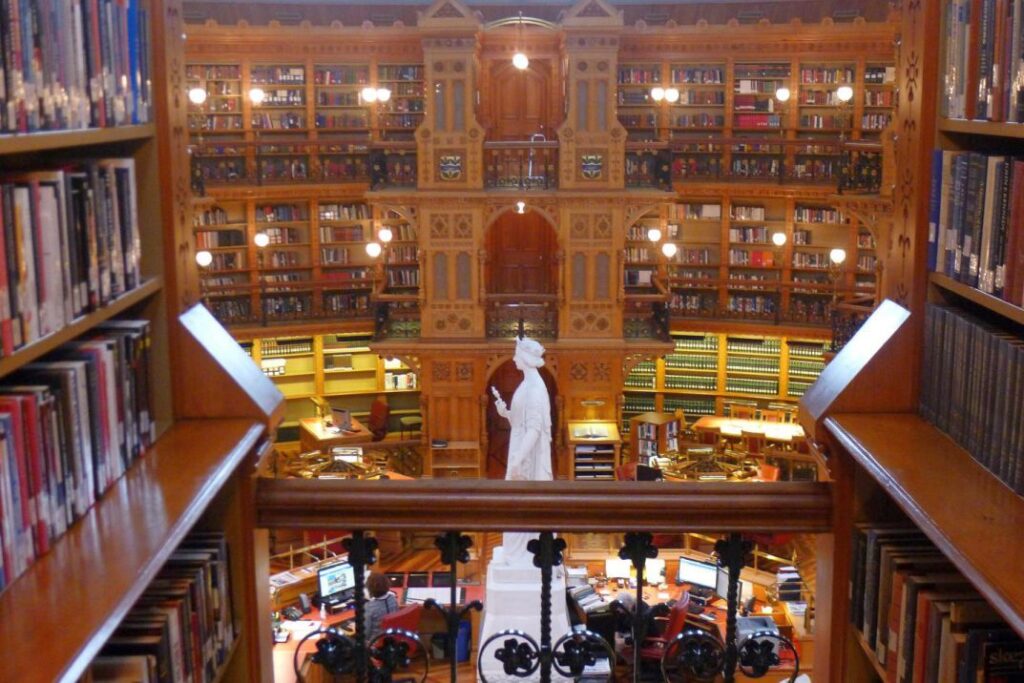

Embassy of Liminal Spaces was inducted into the Library of Parliament with its statue of Queen Victoria, the self-declared Empress of India, under whose reign Nawab Majju Khan was killed. It was Queen Victoria who decorated the man who ordered his execution, Sir John Cracroft Wilson, with the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India.

My mother’s tale resurfaced unexpectedly, far from Moradabad. While in Canada, researching poets, I came across an American doctoral dissertation by L M Lacy about the granddaughter of Lord Byron, “Lady Anne Blunt and the English Idea of Liberty: In Arabia, Egypt, India, and the Empire.”[1] In those pages was an account of Nawab Majju Khan’s death; a miscarriage of justice by a paranoid Empire

Lady Anne Blunt was travelling across the colonized world promoting the Empire. Leaving Egypt, she reached India, two decades after the Great Uprising. In her journal she noted, along with other injustices, the Nawab’s death, “In the aftermath of the execution of the noblemen, a British civilian, Mr Batten, made an effort to convince the government to provide some compensation or at least funds for maintenance of the children of the executed noblemen. His efforts were in vain …Sir A L said …that in times of mutiny and rebellion injustices must necessarily be committed in the haste of action.” Nawab Majju Khan’s case was not unique. Lady Anne began to lose her faith in the Empire and she wrote “It cannot with truth be said that the British Empire in India was ‘founded on justice’—and unless it repents and mends its ways while yet there is time surely the whirlwind must burst over it and shatter it.”[2]

With such grave injustices, Indians began to lose respect for British authority in their blatant disregard for their victims even though “it was afterwards admitted that they had done no wrong”[3] to continue victimising the victims’ families. The rulers did what rulers do: they indulged in cover-ups to absolve themselves of criminal injustice. The man who passed the death sentence without due process, and based on hearsay,[4] was the much-feted Sir John Cracroft Wilson. He went on to receive the highest award from Queen Victoria: the rank of Knight Commander of the Order of the Star of India. The civil servant was henceforth known as Nabob Wilson. The pseudo-nabob lived happily ever after. In the words of the acclaimed poet Jigar of Moradabad,

ab to ye bhī nahīñ rahā ehsās

dard hotā hai yā nahīñ hotā.

Now even this does not remain:

the feeling of pain or the absence of feeling

The whirlwind continued to gather and would finally shatter an unrepentant and inglorious Empire. Though I am five generations removed from the Nawab, the Queen’s death brings back those memories. While I can understand the outpouring of sentiments at her death, it is the eventual demise of the Empire that I will not mourn.

References

[1] Lacy, Lisa McCracken. Lady Anne Blunt and the English Idea of Liberty: In Arabia, Egypt, India, and the Empire. Diss. University of Texas at Austin 2012

[2] British Library, Wentworth Bequest, Lady Anne Blunt journals 53936 17 January 1884. Qt Lucy 2012 p. 186-187

[3] LAB journals, add mss 53936, 18 January 1884. Qt Lucy 2012 p. 187

[4] Lacy 2012 p.187

About the Author

H Masud Taj is the architect of the War memorial for the Indian Navy and Adjunct Professor at Azrieli School of Architecture & Urbanism, Carleton University. He was featured in both the Penguin Book’s “Reasons For Belonging: Fourteen Contemporary Indian Poets” edited by Ranjit Hoskote, as well as “Portraits of Canadian Writers” by Bruce Meyer.

3 Responses

Excellent Historical Information!!!!!

We are descendants Shaheed E Azam Nawab Majeed Uddin khan alias Nawab Majju Khan Of Moradabad,my grandfather Nawab Jamil Uddin Ahmad khan Son of Nawab Wazir Uddin Ahmad khan and My maternal grandfather Nawab yousuf Hassan khan son of Nawab Mohammad Hassan khan who was the son of Nawab Amir Uddin Ahmad khan .

Nawab Amir Uddin Ahmad Khan and Nawab Wazir Uddin Ahmad Khan was sons of Nawab Majju Khan.

Mohammad Saleem Uddin Ahmad (Farooqui )

Saleem.u.farooqui@gmail.com

Mob +919891957025

Assalamualaikum H Masud Taj sahab

Mein bhi Shaheed Nawab Majju khan ke grandson Nawab Jameel Uddin Ahmad khan ka Grandson hoon ,Nawab jameel uddin sahab ke bade bete Nawab Mohammad Rasheed Uddin jo Impirial Royal Air force mein Captain the doosre bete Nawab Razi Uddin mere Father the woh bhi Impirial Royal Aiir Force mein technical officer the , M Rashid Bombay mein Gulistan cuff preid mein rehte the aur Civil line Moradabad mein kothi Bano Bagh mein bhi rihaish thi.

Janab Shuja uddin sahab mere nana nawab yousuf Hassan khan aur hamare dada jameel uddin teseeldar ke cousin the .

M Saleem Uddin Ahmad ( Farooqui )