Public buildings are not autonomous universes. Publicness and urban intent, often rooted in, but not confined to architecture, can shape the lives of neighbourhoods and cities. In this essay, we analyze two recent public buildings in Bangalore – Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) by Mathew and Ghosh Architects (MGA), which opened in 2023, and Bangalore International Centre (BIC) by Hundredhands, inaugurated in 2019. The two buildings, MAP and BIC, have a comparable footprint (of 44,000 sq. ft. and 48,000 sq. ft., respectively); both negotiate tight, urban plots with intense programmatic requirements. Yet, both projects also encapsulate a conceptual excitement and a resultant architectural exuberance, positively contributing to the critical discourse on contemporary architecture in India. The buildings will be analyzed for public intent and architectonic qualities.

Museum of Art and Photography (MAP) is located in a dense, urban neighbourhood, occupying a corner plot. On the north-east, the shorter dimension of the building is experienced largely from motorized vehicles as it faces a busy road, studded with museums. On the north-west, the longer dimension of the building overlooks an upscale residential neighbourhood, registered by predominantly pedestrians. MAP negotiates these contextual cues, along with two seemingly paradoxical demands of creating a porous yet secure museum.

On the motorized roadside, the building becomes a public marker, identifiable in a fleeting glance as a faceted, relatively small, yet bold metal box hoisted by a mushroom column. A scooped-out volume below notionally indicates an entrance, delineating a gentle threshold between the outside and the inside. A digital display on the exterior allows for engaging briefly without entering the building. Principal entrance into the building, on the residential neighbourhood side, requires traversing the barrier of a grilled compound wall. Here, the building starts interacting with a Milan Kundera-ish slowness, all the while with an un-self-conscious contemporaneity, a trademark of MGA. The other two sides (SE and SW) are forbiddingly urbane contexts, blanked out by MAP.

Having arrived at the raised plinth, the entrance to the building affords a visual connection to and from the outside. The outdoor sculpture gallery, on the extended plinth, appears like a quiet tribute to Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion – complete with a palette of glass, steel, and stone (sans the pool) with life-size sculptures territorializing the outside. Experienced from within and outside, this is the most layered and scaled space, connecting to the context sensorially, yet allowing for immediacy with the art.

Ground floor, with the double-height reception, souvenir shop, and a non-ticketed gallery, is relatively more accessible by virtue of the program. The gallery on the first floor, a residual space overlooking the double height with limited viewing distance, along with the auditorium, washrooms, and storage facilities complete the first floor. The 2nd floor hosts a private conservatory, board room, and office, while the 3rd and 4th floors contain the main galleries and library space. There is an attempt to combine the private programs with the galleries so as to not render any floor completely cut off from public presence. However, food as a program, which could have served as a potential activator of public space, is relegated to an easy-to-miss basement and the terrace of the building.

While the floor plates are not discernable from the outside owing to the strategy of a monolithic metal box, the internal volumes are squat, with each floor measuring around 10’, a scale not becoming of an institutional building. The squatness, not to be mistaken for intimacy, is an obvious response to a programmatically loaded brief on a tight site and crippling municipal byelaws.

The material strategy negotiates an industrial aesthetic, with a distinct structure and skin. While the structural system in steel bares its bones on the inside, the girth of the steel stanchions and girders is not commensurate with the scale of the internal volumes. The origami-like, faceted metal skin adorns the outside, making the metal box an identifiable icon. The architects are eloquent of the subversion at the semantic level, having made the façade panels resemble a water tank, alluding to the museum’s role as a ‘container’, literally and figuratively. The opaque facade, meant to keep out the UV rays detrimental to the artworks, hermetically wraps the structure on south-east and south-west.

In contrast, the north-west is transparent, connecting with the immediate neighborhood, especially the large banyan tree. The light from the tinted glass has a psychedelic quality, filtering into the staircase and lobby area, with its tenor changing with the passage of time. The light which enlivens the mute boxes of the galleries, hoisted by the corporeal steel structure, is neither treated like a sensuous material (as in House of Stories, Bangalore, by MGA) nor with austerity (as in the War Memorial, Bangalore, by MGA). It is almost a libertine fantasy, changing with the bellowing wind on the trees, titillating the onlooker from outside—as much a dynamic pop exhibit from the outside as a (rose) tinted connection to the world from within.

MAP subscribes to the quintessential white box museum aesthetic from within while treading edgily on modernist constructs. Given the typological warrant for multiple secure volumes, MAP approaches place making, not as a radical re-imagination of the program but as an iconic image, subverting boundaries less physically and more visually.

The Bangalore International Centre (BIC) is a public institution conceptualized as an organization to promote culturally and socially relevant dialogues, modelled on India International Centre (IIC), in Delhi. BIC is located on an unenviable site, flanked by a sewage stream on the west, in a low-rise, residential neighborhood. Hunderhands, architects of the winning proposal of the design competition state, “Central to the scheme was a public space elevated to the second floor and visible from the street. The extension and elevation of this public space announced the agenda of BIC to be a democratic institution, where public participation was its core concern.” Refreshingly radical as it was, the proposal was eventually abandoned due to emergent exigencies of the site and the municipal byelaws. The essay explores the BIC building as it stands today.

With a large programmatic ask to fit an auditorium, restaurant, café, galleries, conference rooms, and allied facilities, the architects were mindful of becoming a behemoth, bursting to the seams. The design tackles this challenge with an interplay of solid and void on the inside and a façade strategy on the outside. Central to the building is the interiorized, double-height volume with receding floor planes. Not unlike many institutional projects of Hundredhands such as the Neev School, in BIC too, the schema is full of suggestions and possibilities to interact across the building section with floating boxes, architecturally legible as containers, releasing into dynamic, verandah-like volumes. These containers make up the gallery, lecture halls, and similar programs warranting insulation. The axis mundi of the institution is conceptualized at the core of the semi-open like spaces, enlivened ever so organically by double heights, cantilevered planes and referenced by a somewhat redundant “oculus”. These nebulous transitions are potent spillover spaces for exhibitions and pop-ups, scaled further by the textured granularity of exposed brick infill walls. The transition spaces subsequently reduce in area and role on higher floors as the programs become more administrative.

While the building gives primacy to the plan, the section and principal elevation play a pivotal role in activating the central space and modulating perception of scale. Free plan with the east-road-facing façade detached from the floor plates, allows for an independent exploration of the elevation of the building which interacts, albeit visually, with the neighbourhood. A staircase is wedged between the internal volume and the façade. The façade comprises of glass panels in an aluminium framework recuring between exposed concrete fins. The syncopated rhythm of the concrete fins breaks the linearity of the building while the modules of transparent panels, are so composed to simultaneously admit light, scale the internal double-height volume while not giving away the three stories behind, when viewed from the context.

The site of BIC contrasts with the context of IIC, where Joseph Allen Stein was allowed to choose a large verdant site near Lodhi Gardens. BIC had to contend with overcoming its context rather than engaging with it, by blanking out the nala and maintaining a transparent, distant façade within a walled compound. The built is decisively juxtaposed against the unbuilt and the edge conditions do not facilitate incidental interactions with the public domain. This lack of “extensional penetrability”1 as Himanshu Burte calls it, is perhaps a manifestation of the corporate and bureaucratic intent of the donor-driven organization. While the events are non-ticketed, the publicness is more administrative and less architectural.

Given this, BIC strives to fulfill the manifesto of the patron while simultaneously contributing a stately institution to the public domain.

Conservative yet complimentary material palette of exposed brick, concrete, wood, and glass; literal transparency of the façade; light as an ambient reality; wooden panels accentuating the structure in the interiors deployed for treatment of light and acoustics; treatment of the edge condition—all create a corporate modernist idiom for BIC. The project is a softened take on modernism—coherent, rigorous, and moderate at all scales.

Bangalore International Centre and Museum of Art and Photography are significant additions to the contemporary, high-culture landscape to serve the appetite of Bangalore’s burgeoning cosmopolitan population.

Both have unequivocally taken on challenging sites and immense programs, yet making a case for uncompromised rigour in tectonic articulation. Both designs have in common, high attention to articulating the transitional spaces while the containers which serve specific programmatic asks—be it the galleries, auditoriums, or lecture halls, are muted, well-functioning, insular boxes.

However, they both lack in an idealized public intent. As mentioned earlier, this could well be a case of the patrons’ polemic position and construct of what and who is public. Well-meaning as these institutions are, they are elitist, by program and hence by design.

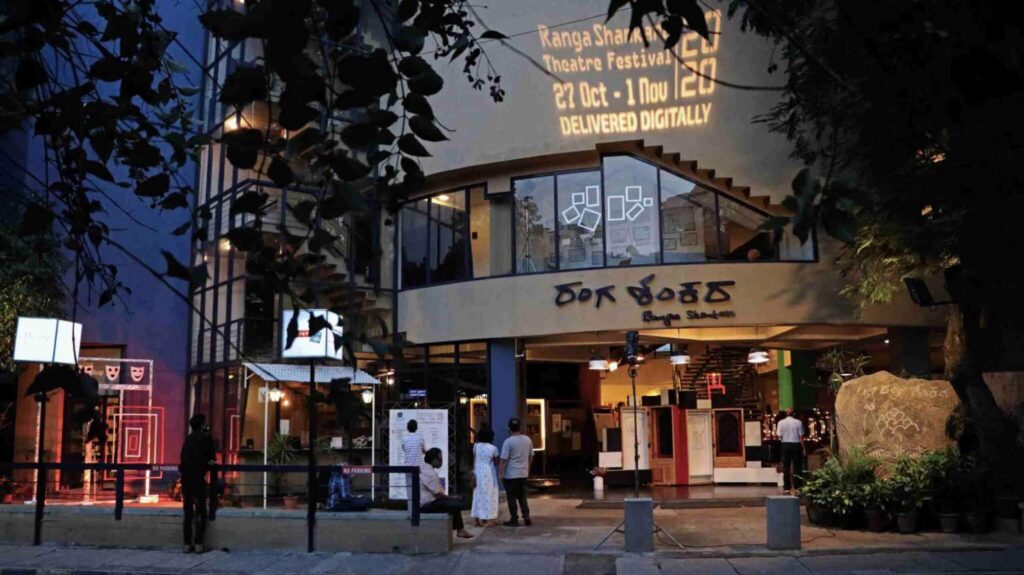

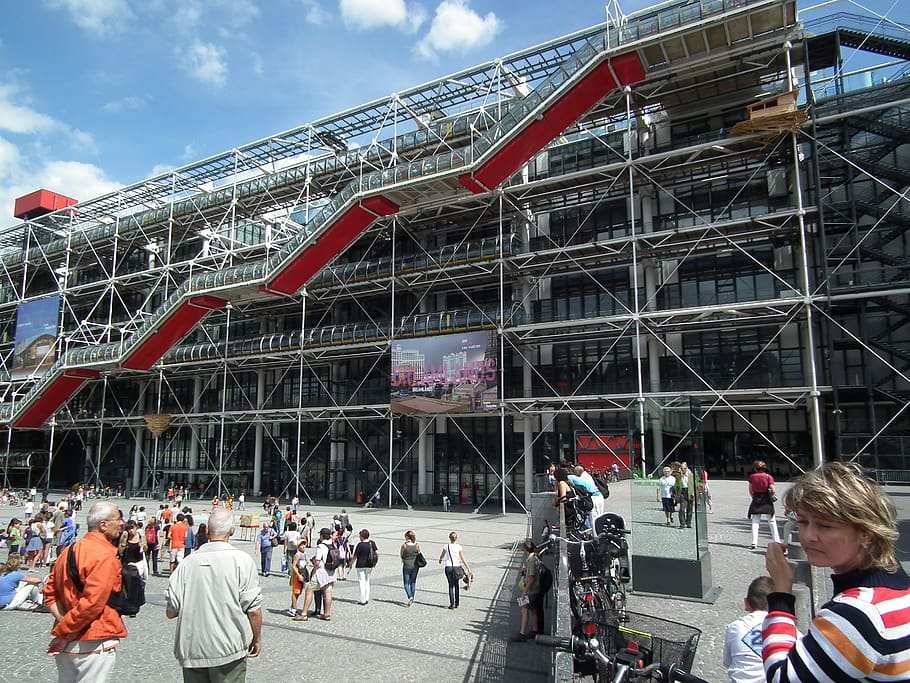

While museums and cultural centres are colonial constructs, its publicness has been widely explored architecturally. One of the most common strategies is the manipulation of ground plane for greater accessibility for passersby as well as itineraried visitors. With this strategy, the earthbound architecture of BIC and the hovering structure of MAP, both could have steered a wider spectrum of people towards the building. For instance, Rangashankara by Mistry Architects in Bangalore, with an uninhibited plinth extending to the road with accessible programs like bookstore and café at the ground level, encourages general public who may or may not intend to attend the cultural program in the auditorium above, to meander in. In another context, in the Deshpande Centre for Social Entrepreneurship by Praveen Bavadekar, Thirdspace Architecture Studio, the semi-open void scooped out under the cantilevered mass of the building allows for unchecked penetrability and loitering within the university campus. Steven Holl’s strategy of deploying an “exoskeleton” and Renzo Piano + Richard Rogers’s Pompidou Centre, with its famed foreground, create vibrant public spaces, drawing people in with an option to linger, participate or further penetrate the building. These gestures at the edge, break the barrier, physically and notionally, to arrive at the threshold of seemingly restrictive public buildings.

Yet another possibility in MAP and BIC was to re-imagine the program to serve as an activator of space, also proposed as ‘event space’ by Bernard Tschumi. For instance, in Seattle Central Library, Rem Koolhaas juxtaposed ‘stable programs’ (like book storage and administrative areas, which need to be contained and secure) with ‘unstable programs’ (like reading area and other spaces which witness public movement) to activate the whole library as a public space instead of the conventional stacking of zones. In many traditional Indian public spaces, a fixed program is not a finite determinant of built-form, like the celebrated 600-year-old Manek Chowk of Ahmedabad. Both MAP and BIC conformed to the program as a given and negotiated for more spillover spaces, rather than re-imagining the program itself. While there are logistical challenges to solve, an attempt in this direction could have layered these buildings spatially and temporally.

Another possibility to increase the publicness is to go beyond the immediate physical and functional ask of the project and devise a robust urban strategy.

James Sterling’s gallery in Stuttgart, with a splicing thoroughfare, funnels the public through the building, becoming an urban experience. In another case, in the Maya Somaiya Library, Sameep Padora (sP+a) reimagines a children’s library in rural Maharashtra as an extended ground plane, wedged between other buildings. The sinuous Catalan vaulted structure becomes like landscape tentacles to be inhabited from within, through and over, offering multiple ways of engagement. While Maya Somaiya Library and Deshpande Centre are part of institutional sites, the architectural gestures have a public intent, allowing for incidental users to engage with the project. Yet another approach is to create identifiable markers in the city activating publicness through potent imageries, like the Bilbao Museum.

Regardless of the strategy – be it at the level of the building edge, program, or as an urban insert aspiring to activate the context, public buildings should, as Stanley Saitowitz states “… be seen as an apparatus rather than an object, as an instrument rather than monument… architecture as a support for dynamic human events rather than favoring programmatic norms and stasis.”2

Good public architecture not only serves its time and place but also becomes part of an enduring tradition of interpreting publicness. MAP and BIC, are welcome additions to the city’s, indeed the country’s, institutional landscape to moot for serious discourse on publicness as an architectural act.

References

- Burte, H. (2007). Space for Engagement: The Indian art place and a habitational approach to architecture (pp. 150). Calcutta: Seagull Books.

- Saitowitz, S. (2012). Simplicity and Synthesis. In K. Frampton, Five North American Architects: An Anthology (pp. 38). Zurich: Lars Muller Publishers.

One Response

The effort to discuss contemporary public architecture in India is commendable as such deliberations are much needed but not very common . The emphasis on ‘ increasing publicness’ by ‘ reimagining the program itself’ is very appropriate. We as Indians have very different notions of public spaces and it needs to be carried forward in contemporary Indian architecture. I congratulate the authors for generating a platform for deliberation on the subject of ‘public architecture’.