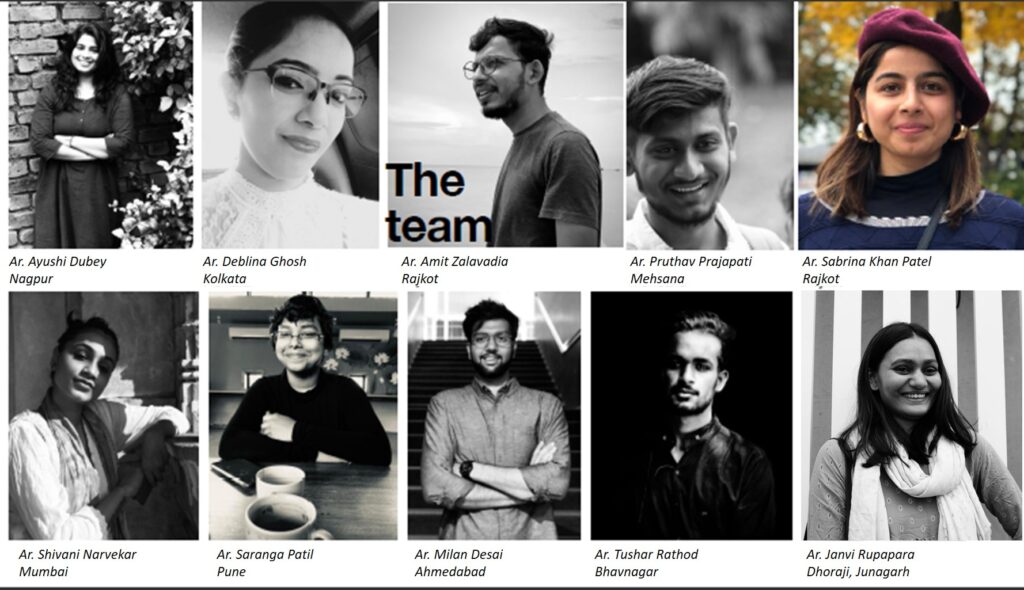

With endless cups of tea from the owners, who were now their hosts, the team documented each wall and corner of the historic structures using a series of processes and techniques.

How a Young Architect led team documented a complex morphology

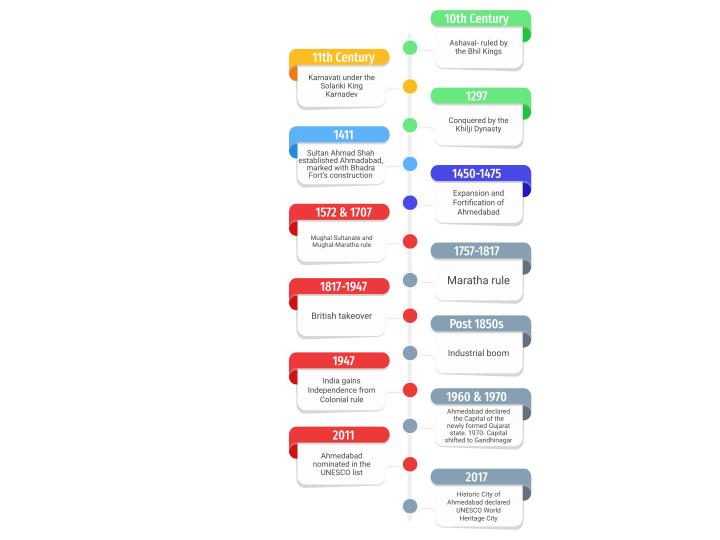

Nestled in the state of Gujarat is a city where the past harmoniously intertwines with the dynamic energy of the modern world. From the origin Ashaval (other disputed names- Ashapalli or Yashoval)1 to Solanki’s Karnavati to Colloquial Amdavad, and eventually, Sultan Ahmad’s Ahmadabad (or Ahmedabad, as it is more widely known)- this collection of vibrant culture has been christened multiple times and ruled over by more- preserving an imprint of each.

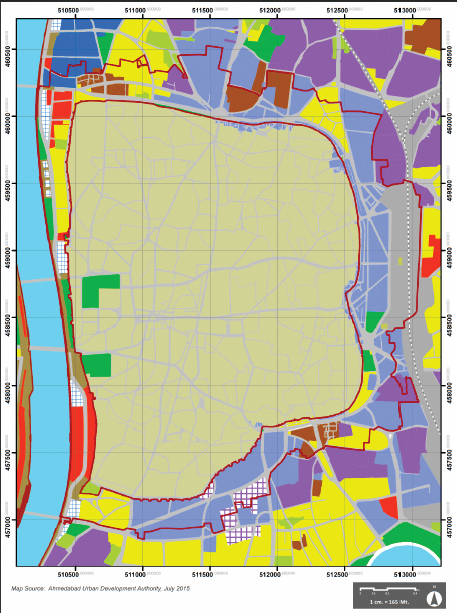

Today, the former Gujarat Capital is an example of the co-existence of centuries-old culture and modern lifestyle. With over 600 years of preserved history, a part of the city- the Walled City of Ahmedabad became the country’s first city (and, as of 2023, the only one, along with Jaipur) to get the status of UNESCO World Heritage City on July 08, 2017.

The walled city of Ahmadabad… presents a rich architectural heritage from the sultanate period… The urban fabric is made up of densely-packed traditional houses (pols) in gated traditional streets (puras) with characteristic features such as bird feeders, public wells and religious institutions.

Historic City of Ahmadabad, UNESCO World Heritage Convention

A regularly updated list, this World Heritage status requires sustenance through constant conservation and upkeep of the designated site- a challenge for a social settlement inhabited for centuries, a complex morphology comprising several structures which gradually decayed over time and the conservation of which vitally calls out for community engagement.

For Ahmedabad, these challenges are preceded by another major challenge impeding conservation and safe-guarding efforts- the absence of an updated database- primarily for the heart of the World Heritage City, where tight-knit communities bound by social ties continue to thrive in the form of Pols.

Traditional settlements, sectors and roads do not work like the other planned areas in the City Masterplan. They are very fluid, with no documentation available nor asked.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

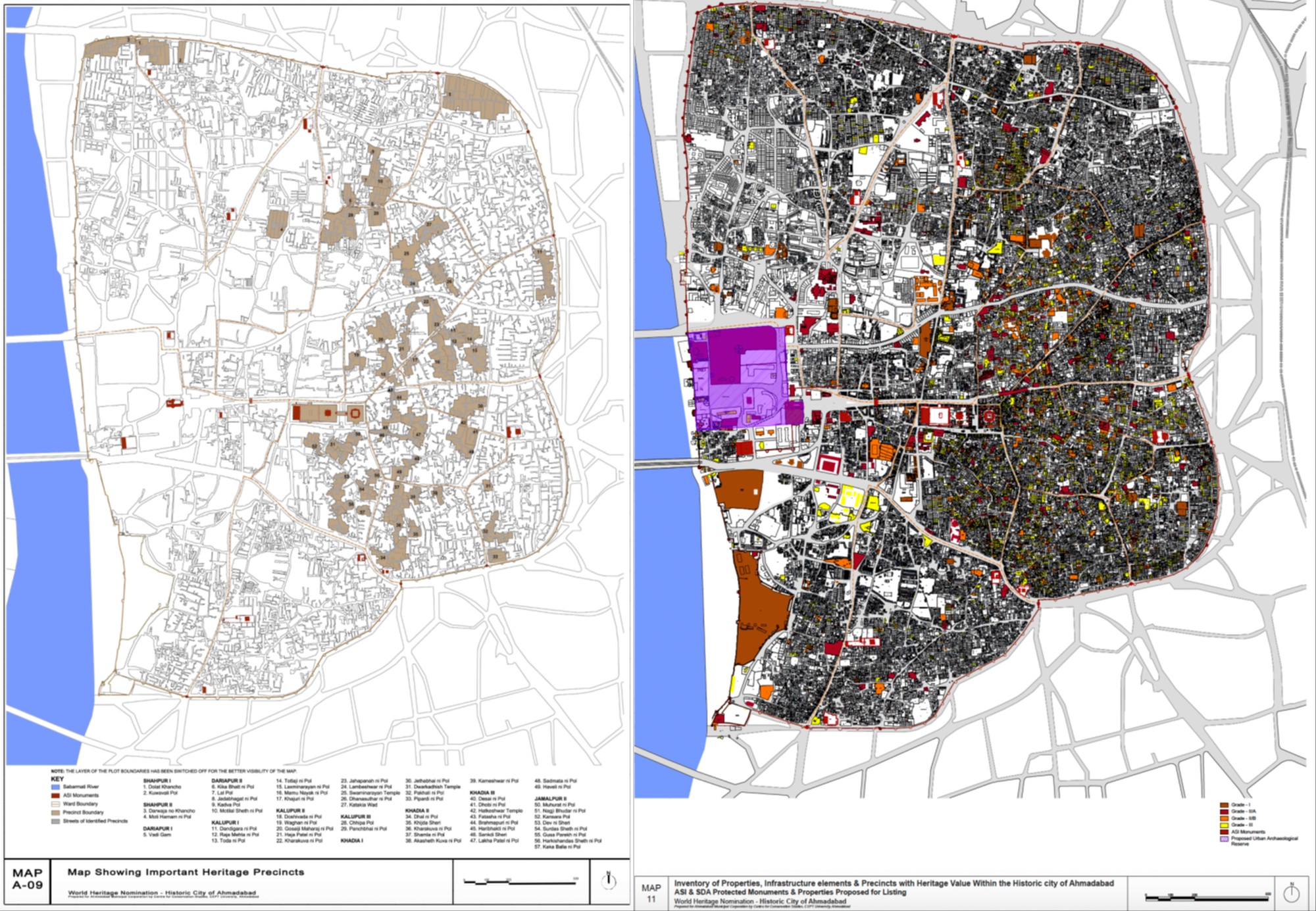

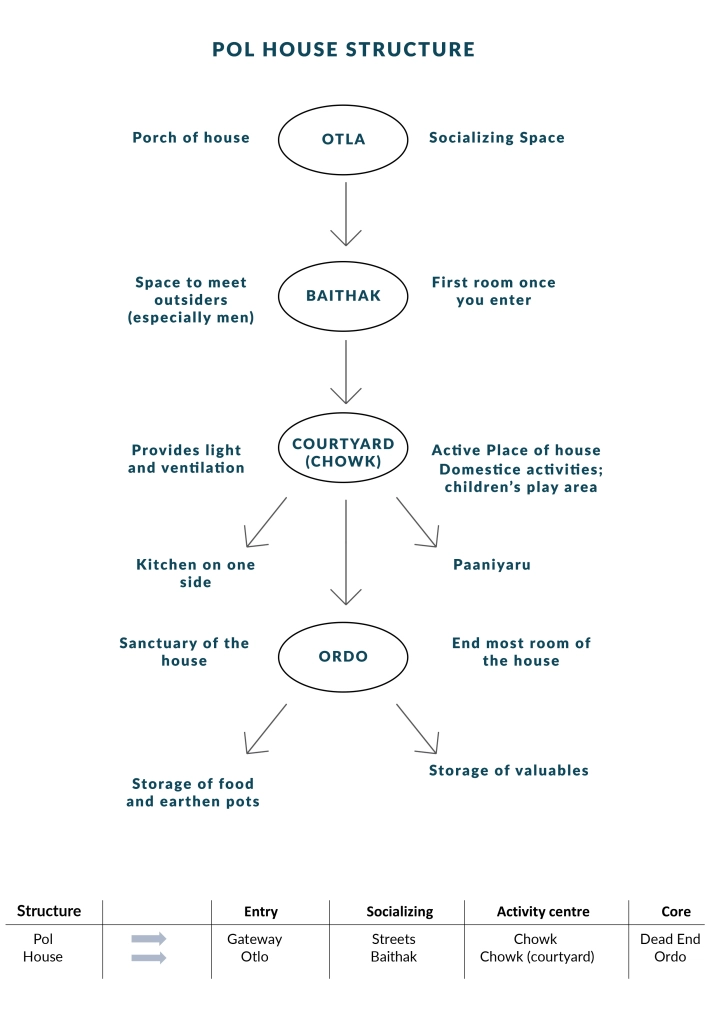

The Pols are the divisions of the traditional Puras (demarcated clusters of neighbourhoods) based on the occupants’ caste, occupation etc.

The community-based clusters of the residential units are a distinctive feature of the Walled City of Ahmedabad’s Settlement Pattern. As the city developed, successive phases of development wrote over existing footprints; such planning enabled better community functioning resulting in stronger associations.

Sabrina Khan Patel

The form of the pols came up during a period of tension due to the constant raids by the Maratha Empire to provide food, shelter, climate protection and water security for a sufficient period.2

Each pol was self-sufficient- with elements such as a pol gate, common well, instruction boards and courtyards as meeting points.

Described as an outstanding example of a traditional human settlement which is representative of a culture in the UNESCO nomination, the settlement pattern continues to witness community living through its self-sufficient houses and community-driven public spaces and forms an integral part of Ahmedabad’s identity as a World Heritage City- a status which relies on the consistent protection, preservation and maintenance of the City Heritage. To ensure this safeguarding of the Heritage and work towards a comprehensive Heritage Management Plan, the Ahmedabad Municipal Cooperation established a separate trust- the Ahmedabad World Heritage City Trust (AWHCT).

AWHCT’s Documentation of the Walled City

With the strife to make informed decisions regarding conservation, the AWHCT implemented extensive documentation of the Walled City in collaboration with several consultants comprising architecture schools, practising architects and heritage conservationists. The objective of the exercise was to comprehensively and accurately document property within the Walled City, particularly the privately-owned timber houses, following internationally acceptable standards while meeting the conditions of authenticity.

The documentation of Timber architecture granted access to knowledge that was otherwise not covered in formal architectural education.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

Adhering to UNESCO’s requirements, the intent of the documentation was to provide material that would, in turn, ensure sensitive, informed decisions and effectively manage changes.

By making informed decisions, it is possible to opt for restoration instead of solely relying on the demolition-reconstruction approach when dealing with dilapidated traditional structures.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

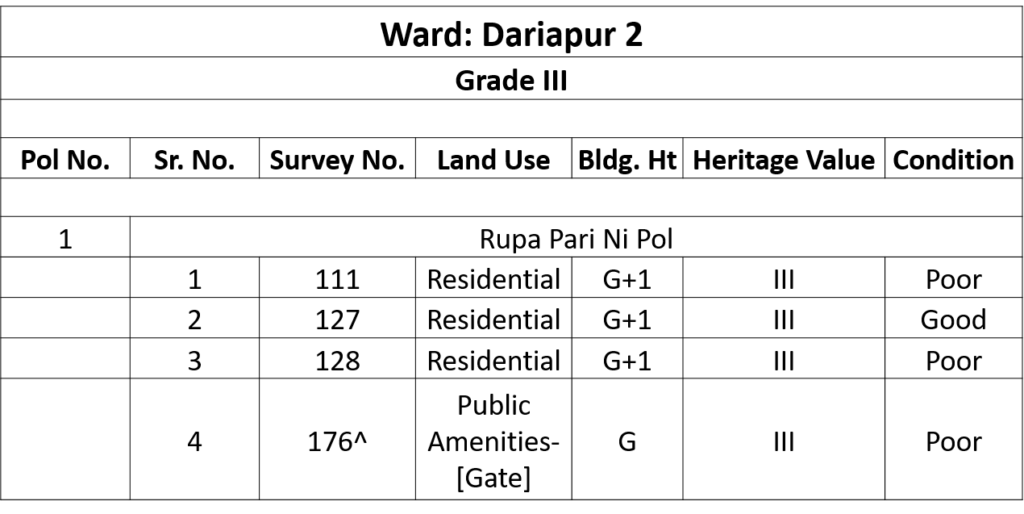

The initial stages focused on listed private buildings and institutions (2692 number), categorized under different grades- Grade I (52), Grade II A (258), Grade II B (702) and Grade III (1680), based on their architectural and historical significance.

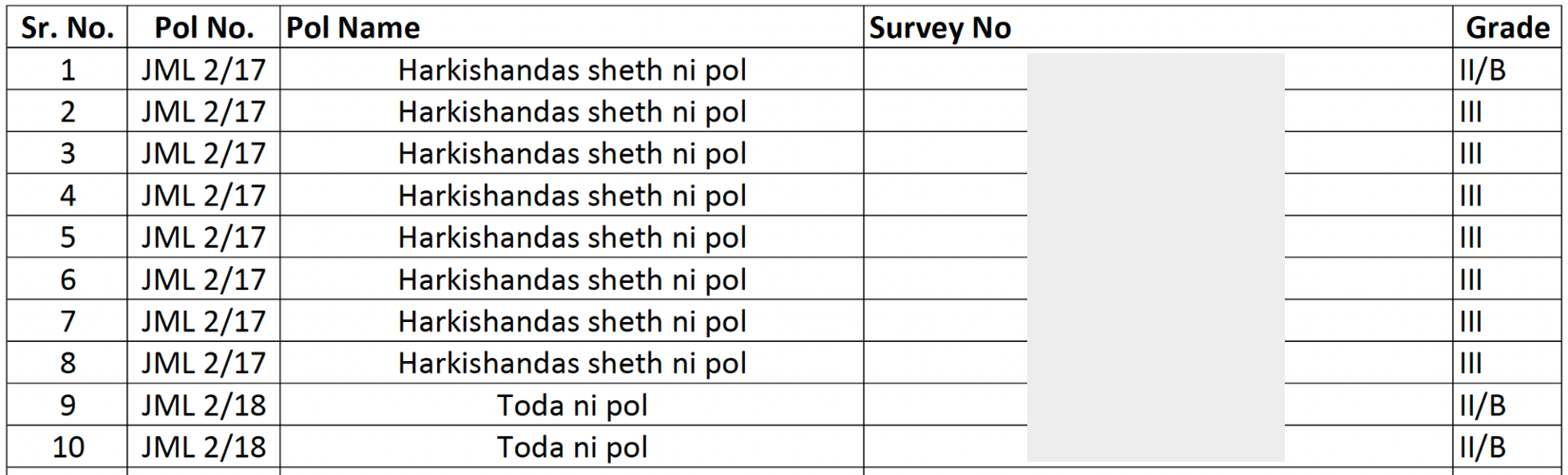

17 project teams collaborated with the AWHCT for this documentation, of which 14 proceeded with the collaboration, which was announced through an EOI (Expression of Interest).

The qualifying criteria were made to encourage young architects and freshers who had the required infrastructure backup to participate in the documentation process. There were no financial requirements, such as a minimum turnover; the only criteria were an architect registered with the Council of Architecture and their ability to produce the required output. Before closing on the association, each team was to produce three samples.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

With qualifying pre-conditions conducive to the participation of younger professionals, young architect Sabrina Khan Patel led one of these project teams.

The project looked potent with experiences of learning, exploring and experimenting with how documentation could be operationalised in living heritage environments. So the initial interest in the work was engaging at the hands-on level with the people who constitute the Walled City while documenting their architectural heritage.

Sabrina Khan Patel

The Rajkot-based architect is a partner at ATKP of Smita and Habeeb Khan Architects. Sabrina established the MM Collective to focus on conservation endeavours and took up this project in consortium with CRCI, Delhi- an organization she was already collaborating with on several work fronts in urban conservation, as the mentor.

Through those prolonged dialogues, sharing of lived experiences and continued professional development in urban conservation, I felt prepared to contribute meaningfully to this documentation effort by the AWHCT.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Documentation by MM Collective and CRCI | One Place, Many Lives: Capturing Inheritances

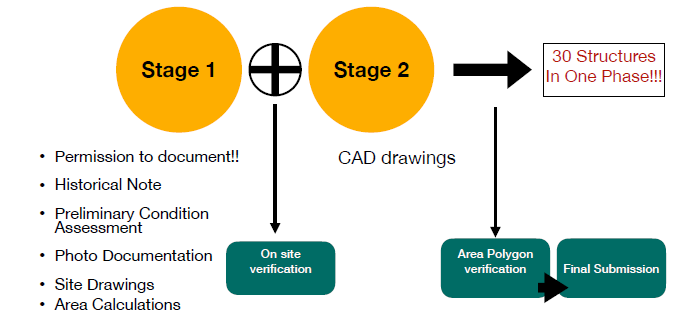

Sabrina led a team of young architects who followed a rigorous procedure to document 30 structures in the first phase.

These structures were all privately owned residences- the documentation of which came with its share of challenges, starting from the first step itself- seeking permission to document. According to Sabrina, obtaining the owner’s permission was the toughest challenge, as the documentation required them to look beyond the external perspective and consider the Heritage’s custody and ownership.

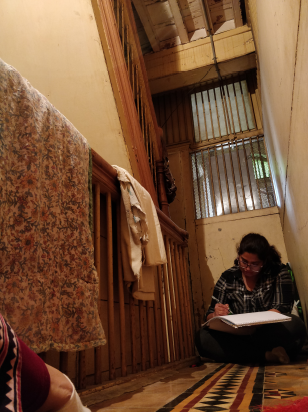

The first step for the team was to garner the community’s trust and engage with them throughout the process. To foster this relationship, a critical aspect was understanding their perspective regarding the heritage they inhabited.

This is where the documentation effort started, at the grassroots level of engagement with the communities which are the custodians of this heritage which we intend to study and record! What matters here is how the people who live here see their heritage and how they see themselves with respect to it. Understanding this relationship and then holding a dialogue with the owners where we discuss the intent of documentation forms the foundation of our relationship with them.

Sabrina Khan Patel

An additional challenge was faced with some of the inhabitants- tenants who did not belong to the local community and had no association with the place.

Reaching out to situations of multiple ownerships, tracing down current ownerships, negotiating with sceptic members of the communities, conveying the need for the effort and so on – the complex and extensive process had its share of challenges.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Process

As community engagement grew, the first “paani ka glass” (a glass of water) marked the beginning of the documentation.

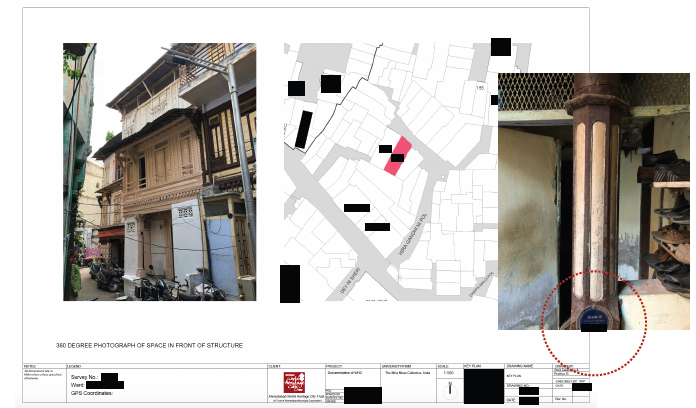

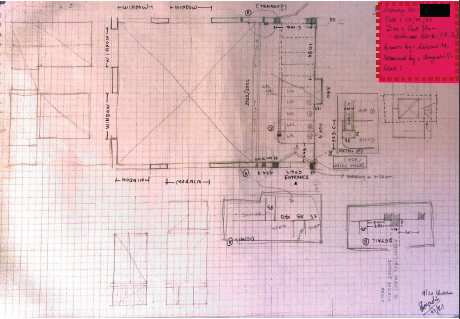

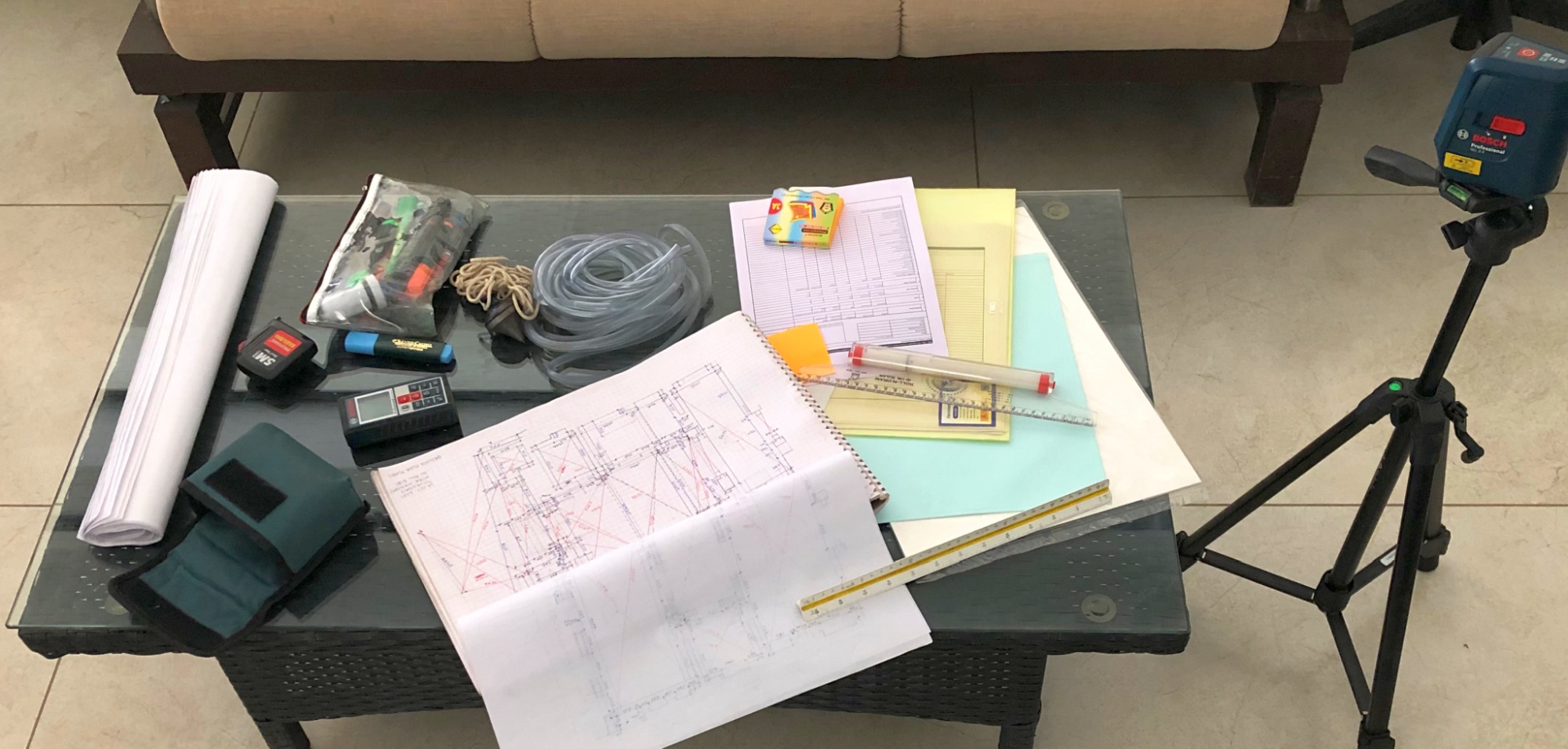

Once permissions were received, recurrent visits to each property followed, as the team relied on a stringent process comprising preliminary condition assessment, photo documentation, site drawings and area calculations.

Usually, our documentation effort starts with a reconnaissance survey wherein we survey the extent available for documentation and understanding of the site surroundings. The structure is understood for its usage patterns, listing status and heritage value, state of maintenance of its different parts, circulation layouts, the relationship of the structure to its extents, edge conditions with its varied physical surrounding contexts etc.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Before starting with the documentation process, the team framed a methodological directive guided by the fact that each structure was to be approached with a unique methodology. This strategy helped the assessment process, which assigned 2-3 days (for on-site measured drawings) to each structure.

When documenting vernacular built heritage, it becomes important to not just map for the architectural details and physicality of the structures but to document in a manner that best represents the embedded knowledge of traditional building systems. This is a significant inheritance and cultural memory of the inhabitants/ community, and documentation presents a tool to hold it in the institutional memory for the Trust as well.

Sabrina Khan Patel

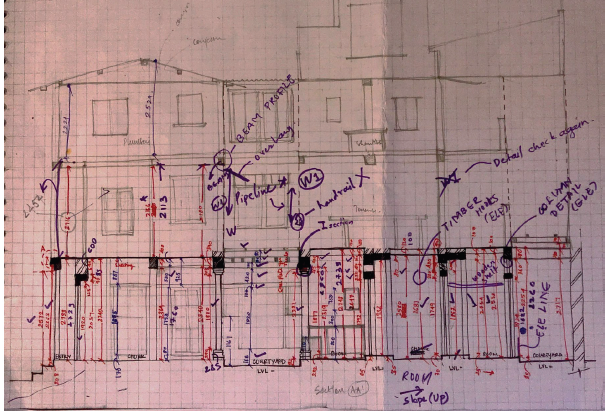

The next crucial step in the documentation was to analyse the structure architecturally and visually, from the scale of the entire structure into its constitutive components, in terms of its material and joineries, smaller elements and decorative motifs.

The key lay in understanding how the structure was maintaining its integrity and finding that repetitive module of the structural system, which yielded the key to its proportions. We tried to focus on the inherent logic of symmetry, geometry, and repetition and work towards identifying an architectural periodisation or style – of which the system may be close to what we saw.

Sabrina Khan Patel

For this step, the AWHCT shared a Historical Note and Preliminary Condition Assessment with each of its consultants, which maintained a systematic record of each structure.

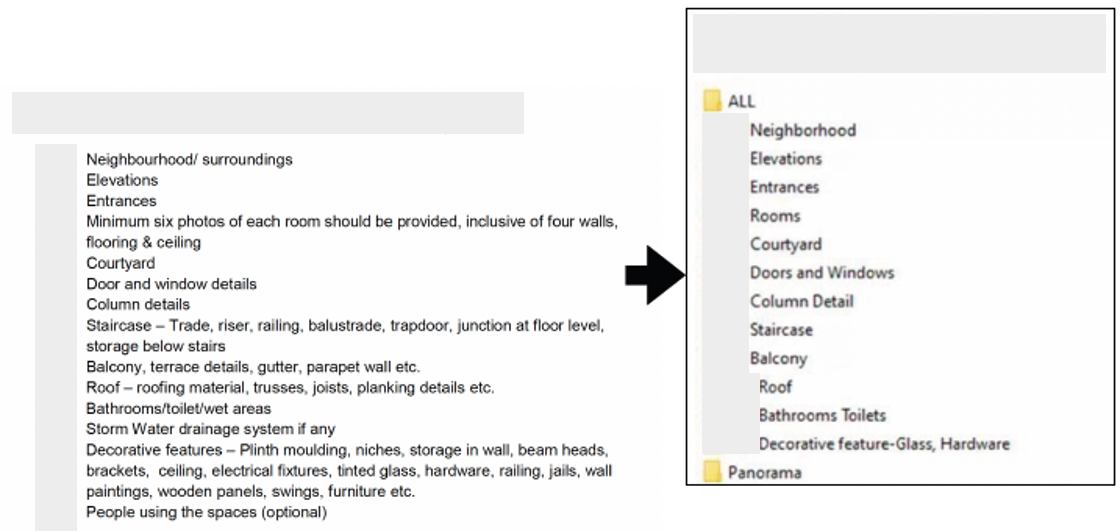

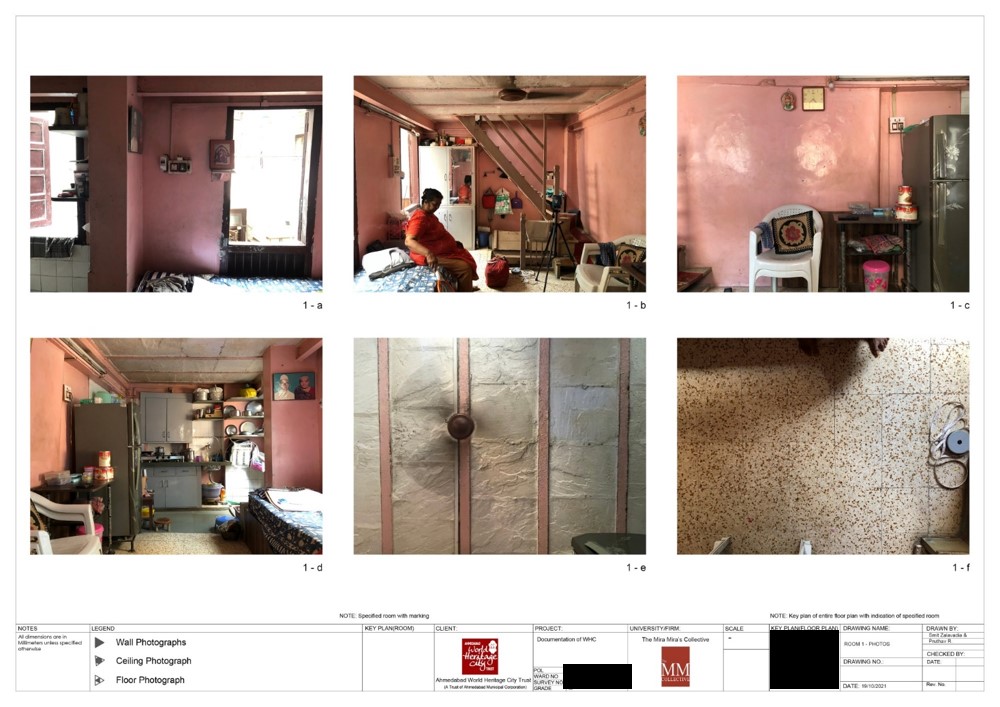

Post this- the team proceeded with extensive photographic documentation of each space within the residential unit.

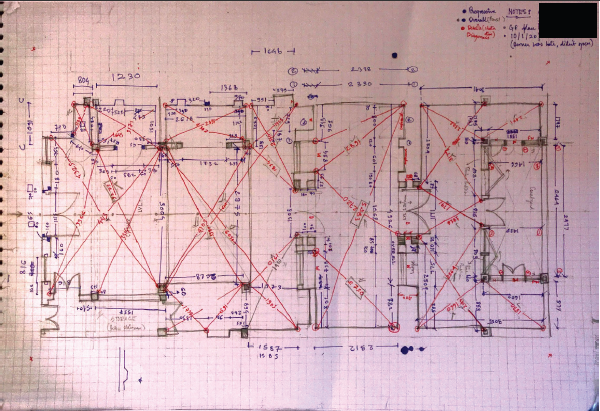

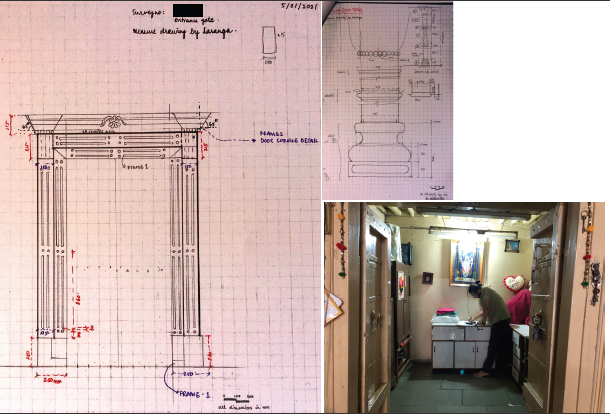

Detailed photograph documentation was followed by measuring and making precise sketches with dimensions, notes and other details.

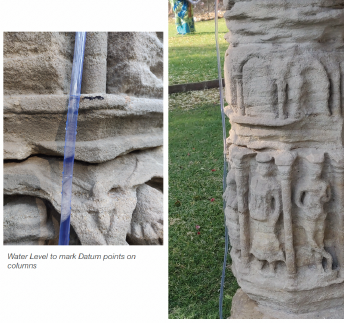

Post the photographic documentation- we moved towards establishing our datum points (for the measurement process) using water level apparatus. After safely establishing credible datum points, we started with measuring and sketching! This same datum was transferred to all the floors where documentation could be carried out.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Arriving at the Datum Point

A Datum Point is a reference point which serves as the base for measurements. These points were marked on columns and walls using water level apparatus and became the zero point for further measurements.

To ensure a smooth process, the team worked in groups of 2-3 architects, relying on detailed site sketches as comprehensive documents with observations, minor sketchings and notes duly dated and following mutually fixed systems. Each sketch was accompanied by a note which mentioned the survey number, the name of the Pol, the name of the drawing, the key plan (if required), the north mark, the date and time of recording, and the team members who worked on the structure. The sketches followed common colour coding- each signifying the axis of the dimension (horizontal/vertical/diagonal).

Diagonals were measured across all spaces, helping transfer the deflections on our digital drawings. You don’t see a deflection in a sketch! You see it emerging from the axes meeting point when you put everything together.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Despite dealing with structural issues, such as inaccessibility in certain areas and unorganized treatments, referring to a datum point ensured measurement accuracy.

Some of the Pol houses we documented were in severely deteriorated conditions where accessing certain parts of the structure was impossible. In many situations, the wall had horizontal and vertical deflections, which had to be documented as well since this was an effort to record the ‘existing conditions’ of the listed heritage structures.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Another challenge was documenting worn-out details. For some, the team relied on conversations with the inhabitants to document these unclear details.

Sometimes, obscured architectural spaces were understood through conversations on-site with the families living in the structures – where the custodians were residing themselves!

Sabrina Khan Patel

In other cases, they would climb surrounding structures to obtain photographs to capture indistinct details and motifs.

In detail, as for the whole structure, the part-to-whole and whole-to-part study, which revealed the structural logic behind the details/embellishment/decorative motifs etc., was the clarity of thought which made for good documentation.

Sabrina Khan Patel

While vague elevation details were cross-checked or obtained through conversations and different angles, for an incoherent structural relationship of components, decayed material was studied.

It is in sections that the construction system becomes visible in full beauty. In places where the structural relationship of components of the building was not easy to understand, we read using places where the material had decayed – leaving us a glimpse of the insides of the structural behaviour.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Surmounting these challenges, the team prepared accurate site sketches, which were then cross-checked by the Trust. The Trust officials re-measured each dimension using the same technique and equipment used for recording by the project team.

Tools and Equipment used by the Project team comprised water level pipes, distometers/ electronic tape, measuring tapes, plumb bobs, angle sections and protractors, DSLR camera, IPAD with sketching tools, tools such as ACAD and stationary such as portable drafting boards, rulers, graph paper etc.

Arriving at CAD drawings

The Site sketches and photographs were then translated into technical drawings. Detailed photographs were clicked of each detail, which was then rectified on image-correcting software, such as Photoshop, using outer profile dimensions to obtain the correct scale. With measurements from the sketch drawings as a reference, these photographs were rastered to produce CAD drawings.

All walls have undergone deflection, horizontally and vertically. So, we can’t assume the right angles anywhere!

Team MM Collective

The CAD drawings were accurate and detailed documentation of all the dimensions, projections, floor levels, door window schedule, inaccessible/unknown areas, architectural materials and materials variation.

Challenges, Learnings and Understanding Limitations

Precision and accuracy were the team’s primary objectives. However, they were also aware of the limitations that came from the fact that they were documenting heritage inhabited for several centuries. Encroachments, weathering, and structural deterioration were additional challenges throughout the documentation process.

The form of the settlement makes it difficult to isolate a structure from its surroundings. We have documents that convey neatly drawn lines of ownership, but it is while documenting that one gradually realises the full complexity and richness of spatial, structural, architectural, behavioural and human interdependencies.

Sabrina Khan Patel

Considering these limitations, the team decided on guidelines that gave them clarity on the level of precision required for various details. They prioritized exterior parts as the most important detail, given their contribution to OUV (Outstanding Universal Value). Traditional Furniture was to be documented in depth, while the interior parts- the newer additions, could be at a basic level.

Where weathered structure became a challenge, a newly constructed structure made the team speculate its listing. Narrating an amusing incident, Sabrina shares,

There are interesting instances where one wonders why a structure could have been listed at all. We came across a similar situation, where a 3-storeyed building had recently constructed storeys. We wondered what was expected out of this listing! As our understanding grew, we learnt that the structure was standing over a passage- a gateway into a small khadki. The passageway used by the community to cross over into other public areas was situated underneath private living quarters- this was where the historic value lay! It was one of the last surviving examples of this type of Pol housing! So again, the intent of documentation plays a crucial role in deciding the methodology which is pursued in order to document!

Sabrina Khan Patel

These revelations were exciting details for the team. However, they decided to refrain from expressing the significance of the Pol houses for the architectural community to its inhabitants, choosing against advocating this importance.

What we are dealing with here is more than an object of evaluation and scientific assessment. We are dealing with material memory, personal history, their sense of self-identity and their aspirations for a future (which may or may not have this inheritance!). Except in situations where institutional intervention to advocate for conservation is necessary, the people who inherit the inheritance usually have their own systems to take care of what belongs to them. The question here is – who’s heritage are we talking about? And then, how (in what light) are we talking about it?

Sabrina Khan Patel

An accurate documentation of inhabited private property- the home and livelihood of its occupants, the extensive documentation of the Ahmedabad Pols is perhaps a first-of-its-kind attempt. By involving the local communities, its intimate nature extends beyond the inanimate heritage.

We cannot document the structure without engaging with its contents- here, the living culture and the people with all their activities! When the task at hand is to record the physicality of spaces of someone’s everyday life, the record, even though architectural in method and outcome, capture intimate details of their life! So, to ask permission to document their homes and assets is a tall and personal demand.

Sabrina Khan Patel

The documentation process reveals a story of associations, sentiments, scars, experiences, events and occasions. Keeping the nature of the required details in mind, the team set up boundaries to delineate what will be appropriate and what won’t. This agreement between the team and occupants was subjective, varying from home to home.

As each survey number on their list introduced them to a different structure and a home, the team’s attachment to the place grew. They managed to break down the bigger world of communities into individual worlds each home had created.

The documentation opened up ways of seeing the world- previously unknown to us and taught us to make our place in the world. These neighbourhoods are constituted based on community linkages, and there are close ties between members of the communities. Many of these communities still have a working stratification for collective decision-making. Oftentimes, in such situations, natural leadership may co-exist with formal leadership. This means there would be invisible systems of power and influence within communities leading to unanimous notions of what the community would be cooperative in.

Sabrina Khan Patel

While the process gave the architects their share of takeaways and learnings, they hope their interactions encouraged the inhabitants to reflect on their heritage- one of which they are a part of.

There are equal instances of heritage being perceived as a resource against being perceived as a liability. The factors which determine how custodians arrive at these are beyond our agency. But, I hope our small engagements with them made them pause and reflect, especially the younger generations.

Sabrina Khan Patel

With the documentation process proceeding, several owners have expressed their willingness to restore their property. The Trust will act as a support system for the inhabitants, providing them with precise drawings and consultation.

While handing over the drawings, we will encourage the owners to apply for restoration. This will lead to a transfer development rights certificate, thus providing them with financial aid. Restoration and partial reconstruction, in certain cases, will also generate more employment for traditional craftspersons.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

Sabrina’s association led to documenting 30 structures- a small part of the over 2000 structures marked in the Walled City. 13 other teams were involved in the documentation of the Walled City Heritage Structures.

Prior to this exercise, the database primarily consisted of structures that had been restored using various funding methods. On the other hand, while there are books available on the settlement’s architecture, they primarily focus on the form rather than emphasizing the extent of damage the structures have endured.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

The lack of an up-to-date database is continuously cited as one of the primary reasons obstructing informed decisions regarding the conservation of heritage, in particular, dilapidated and weathered. While the Walled City of Ahmedabad currently enjoys the World Heritage City tag, it is important to understand that this volatile status needs to be maintained. As per the recent meetings of the Heritage Conservation Committee, several loopholes, ranging from lack of funds to management of the committee issues to the lack of a revised database listing the heritage structures, possibly threaten this status⁴.

The Walled City Documentation comes across as a promising initiative catering to at least one of these issues. In addition to navigating through the challenges presented by the COVID period, the exercise encountered multiple obstacles, such as obtaining the consent of owners, effective management of resources in collaboration with consultants, and the difficulty of documenting deteriorated structures during rain and, to some extent, extreme heat.

Though this is a one of its kind initiative by a city towards its heritage, one suggestion would be to do the documentation through advanced digital techniques, which allow a faster, more accurate and more efficient method. The documentation effort would be more effective when tied up to a city-level drive focused on sharing an understanding of heritage documentation as a city-level resource accessible to all.

Sabrina Khan Patel

If successfully implemented, Ahmedabad- the first Indian City to become a UNESCO World Heritage City, might also emerge as a frontrunner in maintaining this recognition. It can play a pivotal role in inspiring other departments and regions to establish a stronger connection between their cultural heritage and local communities.

No city in India has regulations specifying the heritage elements. For our protected monuments and structures, we continue to have a no-touch policy, even for those that demand restoration. Restoration is considered Falsification. But, this cannot be followed for living heritage. This documentation could thus give birth to new policies in this direction.

Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

References

[1] Historical Glimpses, Welcome to Ahmedabad.com, A complete city guide by Dr Manek Patel ‘Setu’

[2] Second Session: Pols of Ahmedabad, Lecture – Life in the Pols by Neelkanth Chhaya, Monsoon Semester 2020, CEPT University, aht2020richa.wordpress

[3] The Gujarat Government Gazette, Vol. LVI] 29th June, 2016, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation

[4] Ahmedabad’s Unesco WHC status faces monumental challenges, Paul John, Times of India (April 06, 2023)

Bibliography

- World Heritage Nomination Dossier- Historic City of Ahmadabad

- Listing and Grading of Heritage Structures, Volume 1: Listing database of heritage structures in AMC jurisdiction, Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, December 2014, Prepared by Indian National Trust for Art and Culture (INTACH) Gujarat Chapter

- Ashish Trambadia, Director of AWHCT

- Sabrina Khan Patel

- The Criteria for Selection, UNESCO World Heritage Convention

- Historic City of Ahmadabad, UNESCO World Heritage Convention

- History, Amdavad Municipal Corporation, https://ahmedabadcity.gov.in/

All images courtesy (unless credited otherwise)- The MM Collective

One Response

Excellent work. Not only a very useful documentation but a true labour of love. I hope this work reaches the maximum number of people. Wish this team extend it’s scope to many other historic ,living cities.My warm regards and heartiest congratulations.keep going,all the best.