Architecture admissions this year, after a prolonged extension, have ended, and anecdotes of uncertainty are trickling in. Many colleges struggled to meet 50% enrolment figures. Post-graduate admissions have been bleaker than undergraduate admissions, and there are reports that a few colleges witnessed admissions in single digits and had to shut down. Some argue that reduced undergraduate admissions have been recurring while severe reductions in postgraduate admissions were waiting to happen. What is the actual extent of the problem? What lies beyond the anecdotes?

In this article, we analyse the enrolment figures, the number of colleges that have applied for closure, and registration data to determine the current state. We ask whether the situation is a case of concern. If it is, what should be done?

Our analysis of the undergraduate enrolment data shows that the problem is far more serious than one would imagine. The problems have been accumulating, and the diagnosis has been misplaced. While the numbers have been calling for immediate changes, the actions on the ground are yet to measure up to the urgency. This study argues for radical changes to the regulatory framework, providing autonomy to institutions, placing the onus of ensuring quality entirely on them and re-examining the profession’s role.

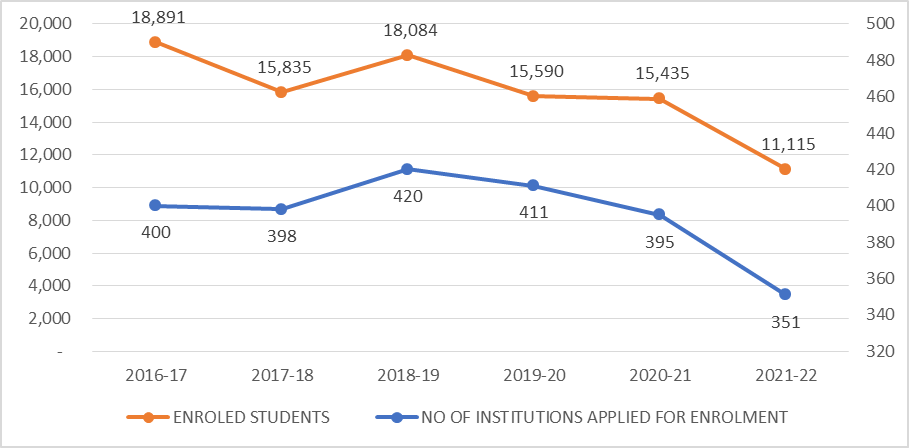

First, the enrolment numbers This study analysed the number of colleges offering architecture programmes using the data available in the various annual reports from 2016-17 to 2022-23, published on the CoA website. Over the last six years, enrolment in the B.Arch programme has reduced from 18,891 students to 11,115 students, about 41 per cent. Correspondingly, the number of colleges that have applied for enrolment has reduced from 400 to 351, a 12 per cent reduction, indicating the number of colleges that have either shut down or applied for closure has increased (Council of Architecture Annual Report 2021-22– coa.gov.in. Pg. 31. Last accessed October 2023). More of this later.

Fig 1: B ARCH ENROLMENT AND NUMBER OF INSTITUTES

Source: Council of Architecture Annual Report 2021-22– coa.gov.in. Pg. 31, (Last accessed October 2023)

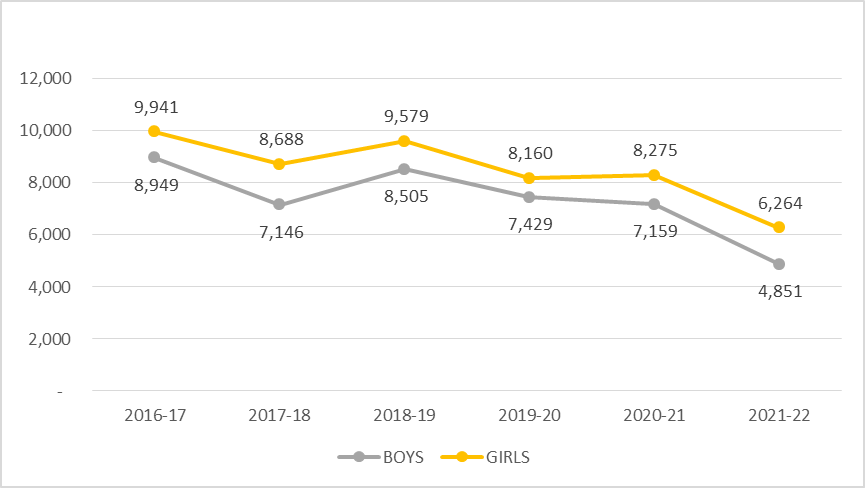

The gender distribution of student enrolment points to a changing pattern (Fig 2). The number of male students enrolling in B.Arch has declined more than that of female students. Between 2020 and 21, the number of female students declined by 2000, while in the case of male students, it was about 3308. (Council of Architecture Annual Report 2021-22– coa.gov.in. Pg. 31, Last accessed October 2023). Whether this indicates any shift in preference or perception on gender lines is too early to tell and would also require further surveys.

Source: Council of Architecture Annual Report 2021-22– coa.gov.in. Pg. 31 (Last accessed October 2023)

Impact

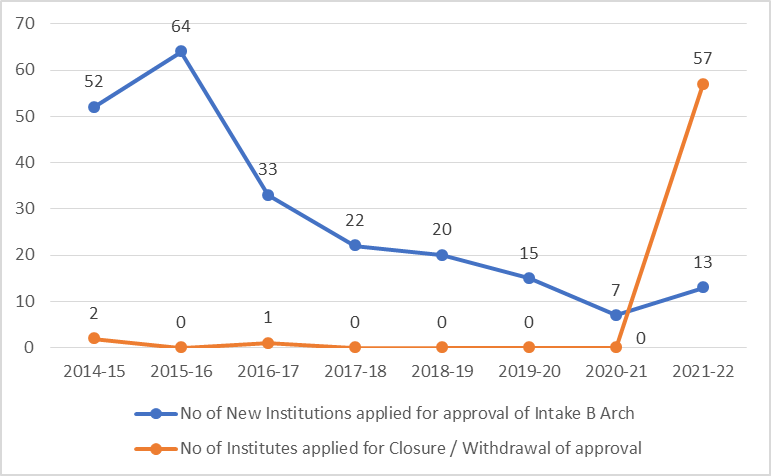

The lowering enrolment figures have had a serious impact. Colleges have struggled to sustain, and about 57 have applied to CoA for closure. Though this appears to be a logical conclusion of falling enrolment numbers, it is intriguing that the new colleges were also opened during this time. About 13 new colleges applied for CoA approval to start B.Arch in 2021-22 Council of Architecture Annual Report 2021-22– coa.gov.in. Pg. 31 (Last accessed October 2023). Though the number of new colleges may have come down from the levels witnessed in 2015-16, the current applications to start new colleges defy any simplistic correlation between lower intake and the shutting down of colleges.

Source: Council of Architecture Annual Report 2021-22– coa.gov.in. Pg. 31 (Last accessed October 2023)

Wrong Diagnosis

How do we understand these figures? A hurried diagnosis will blame the supply: there are more colleges and seats than what we need, will be the argument. To those who hold this view, a fall in enrolment numbers is a market correction and not much to worry about since we are heading to a magical balance. This view is not well founded and distracts from the real problems.

The strong economic fundamentals suggest a growing demand for architects. India needs skilled professionals with increasing urbanisation, extensive infrastructure development, robust economic growth, increasing investments, and climbing per capita earnings. This is further reinforced by the recent Knight Frank-RICS report on the construction sector, which states that the outputs from the real estate sector `is estimated to grow to USD 1 Trillion by 2030 from the current USD 650 Billion’.[1] As the CoA Perspective Report of 2020 notes, only two of every 100 buildings constructed are designed by architects. This indicates that the problem is not entirely a demand shrinkage but that of market penetration and further need to demonstrate the value of architectural design. Lower salaries are also an issue. More of it later.

Returning to the drop in enrolment, it is imperative to correlate the figures with the college locations, quality of teaching, industry perception of employability, and their willingness to pay for architecture graduates.

While many colleges could be falling in enrolment, some have consistently done well. If it is a market correction, they have been spared. Studying them carefully would indicate that more issues are at play and that quality of education is the key determining factor. A related issue that calls for scrutiny is the difference between colleges in large cities that enjoy professional support and face fewer faculty hiring issues and colleges in smaller places with poor industry connections and difficulties in hiring competent faculty.

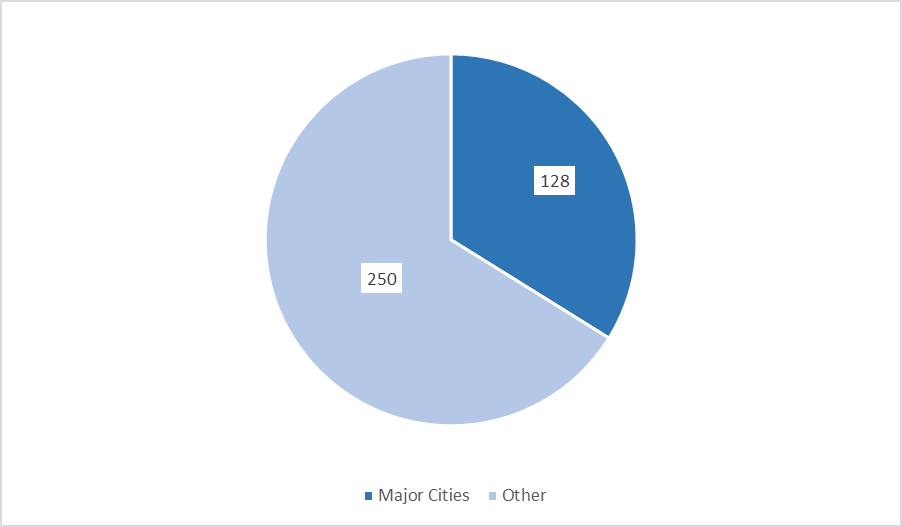

Institutes in Major Cities

Source: Institutes approved for enrolment in UG Programs 2022-23– coa.gov.in. (Last accessed October 2023)

Of the 378 institutes offering B. Arch programs, seven major cities of New Delhi, Mumbai, Pune, Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Chennai, and Coimbatore have ten or more institutes each. Together, they have 128 institutes, or about 34%. Almost half of the 148 institutes with greater than 40 intake are located in these seven cities. Urban centres offer more opportunities to practice and for the teachers’ partners, which are becoming important considerations in hiring. They also offer students better industry connections, making it easier for practitioners to teach as visiting faculty. There could be a few institutes in major cities that have struggled with enrolment, but the probability of survival seems higher, due to availability of teaching talent pool.

CoA’s Perspective Plan

Policymakers seldom understand these enrolment and supply-side nuances, and, as a result, their recommendations have been misdirected and, at times, harmful. The CoA’s `Perspective Plan for Growth in Architectural Education,’ published in 2020, is a case in point.[2] The Perspective Plan is meant to understand the demand for architectural education and improve delivery.

While it agreed that the country needed more architects, almost twice the size in 2020, the report identified a different supply problem. It blamed the imbalanced distribution of colleges and registered architects as the problem.

Drawing from the study on the number of colleges and architect registration data in every state, the CoA report observed that in states such as Bihar, there is one architect per 2 lakh population and one B.Arch seat for every 29 Lakh population. Orissa has one architect for every 52,000 people and one B.Arch seat for every 1.56 lakh. In contrast, Tamil Nadu has one architect for every 9,503 people and one B.Arch seat for every 18,500 (Diu (Perspective Plan for Growth of Architectural Education. CoA, August 2020. Pp 6-7. Last accessed December 2023). Hence, the CoA concluded that the main problem is the distribution of colleges and seats and divided the country into green, yellow, orange, and red states based on the number of colleges and architects.

There are 14 green states (Category I ), such as Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar and West Bengal, where new colleges are needed and will be encouraged. About four yellow states (Category II), such as Andhra Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, where colleges will be permitted but on a low priority. The 12 orange states (Category III), such as Punjab, Parts of Maharashtra, Parts of Karnataka, Haryana and Goa, are low-priority areas where the admissions are controlled. New colleges will not be considered in the red areas (Category IV) such as Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and large cities in Maharashtra, Lakshadweep Islands, Daman and Diu (Perspective Plan for Growth of Architectural Education. CoA, August 2020. Pg 33. Last accessed December 2023). These recommendations are in force. The CoA – Approval Process Handbooks (2022-23 and 2023-24) have mandated them.

For now, let us sidestep the question of the legal basis of such decisions and instead focus on the rationale and efficacy of the recommendations. Population number, which CoA has relied upon, cannot be the sole determining factor. Economic factors and the professional opportunities each state or city offers are influential. Also, access to practising architects to support teaching and improve education is another critical point to consider.

Many colleges in locations with less or no access to practising professionals have struggled to keep up the quality of training. According to the CoA’s data on registered architects, the number of professionals is higher in what the CoA would call red states or areas, and understandably so. The state of Maharashtra has 33,419 architects with active registration with the council, and in comparison, the state of Jharkhand has 630 (Council of Architecture Annual Report 2022-23– coa.gov.in. Pg. 24, Last accessed December 2023). Many of the 33,000 architects in Maharashtra would have completed their studies in other states and then moved there in search of better professional and practice opportunities. Demand for architectural services is market-dependent and varies. Any intrusive regulation or quota system will fail and may not be the right way forward. The quality of education is at stake, and improving it is the solution.

Issues and Way Forward

Structural issues

Some of the problems with architectural education are structural, and they can be fixed if there is will. The first issue is that of organising academic programme.

The five-year undergraduate course is among the longest professional programmes. Architects end up studying longer and paying more for education. More importantly, the current structure restricts choice and impedes specialisations, leading colleges to produce cookie-cutter programmes that reduce employability.

Many countries also take a five-year education as the minimum for professional licensing. However, they divide it into two manageable parts, offering students choices and a post-graduate degree after five years. For example, the UK system divides five-year education into three plus two years, where the first three years are at the undergraduate level, which is broad-based. After three years, students can choose an area of specialisation or do an intense domain-specific programme. After two years of work experience, if they choose to, students can take a licensing exam to become practising professionals.

The advantage of the three-year-plus two-year model is that it helps students to make clear choices. After completing three years of undergraduate programme, they are not only ready to work in offices at a junior level, but after some work experience, they can enrol in two-year programmes and take a well-defined professional route. Alternatively, it enables interested students to choose research paths or career shifts. There is no such choice currently in India, leading to less diversity in academic programmes and a limited scope for innovation.

The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 offers an opportunity to course-correct. It prescribes a reduced undergraduate period, increases choices and gives institutions more autonomy. This means fewer centralised regulations and more responsibility for colleges. However, CoA has yet to embrace the opportunity fully. Some fear that the reduced undergraduate education will impede professional competence. They overlook that there is no dilution in professional training in the three plus two models. Instead, there is more focus, enhancement in mandatory professional experience and the scope for a rigorous licensing exam. Furthermore, five years of education leads to a post-graduate degree with more choices.

Another structural issue that needs to be fixed is the overloading of subjects and unreasonable credit demand, which severely affects the quality of teaching. Many colleges, on average, teach 260 to 300 credits. This translates into seven or more subjects a semester, beyond a manageable workload for students and teachers. A survey of international best practices would indicate that anything more than 20 credits and four to five subjects a semester is not advisable. It is impossible to teach everything under the sky. And it is not needed too.

Institutions perform only a part in making an architect; the rest is completed in practice or research. The institutions must admit to their limited role, define it and perform well.

Education Quality

Professionals and recruiters have regularly raised concerns about low employability and how much time they spend upskilling fresh graduates in their offices. In defence, academics explain that they do not train students for first employers but aim toward the student’s long-term growth. Hence, fresh graduates’ inability to meet their immediate employers’ expectations is not a serious issue in their view. This is not a helpful position to take.

One must recognise that students’ long-term development will be impaired without basic skills and comprehension. Furthermore, many fresh graduates seek immediate employment, and their low employability will not help.

Where does the problem lie? Is it in the content of what is taught, how it is taught or in the absence of opportunities to self-learn? Colleges quickly point out that they follow CoA norms and syllabi and are not to be blamed. At one level, this is true. CoA minimum standards prescribe credits, contact hours, student-faculty ratio, and a detailed syllabus. CoA Inspections try to ensure colleges follow the prescriptions. However, this arrangement produces a false sense of quality since the outcomes are never audited.

It is important to recall that CoA’s mandate is to improve professional standards, and its power to regulate education emerges from that context. Without reviewing this connection, merely regulating education is bound to fail. As in the case of many architectural registration boards worldwide, defined graduate attributes should be tied to the licensing requirements. They leave it to individual colleges to find their ways to achieve them. In such an arrangement, colleges take full responsibility for the quality of the graduates. They either articulate the professional licensing route or alternative streams, such as research and policy studies, based on their strengths and aspirations. This is not the case in India. Current measures of regulating architectural education are based on stand-alone input features such as teaching hours, infrastructure, etc. Only recently, for the first time, CoA circulated a draft document briefly defining graduate attributes. However, more work needs to be done in this direction to ensure better quality education in line with the spirit of the NEP.

More importantly, the institutions must be empowered to take full responsibility for delivering quality education and be held responsible. Intrusive or overreaching regulations will not help.

Institutional Capacity

Careful faculty recruitment and infrastructure creation, among many others, are critical to improving institutional capacity and, thus, quality of training. Creating an institutional environment to work with possibilities of intellectual growth and career advancement is essential to retaining talents. It is a positive loop: supportive institutions get better faculty, better faculty improves institutional capacity, and good institutions attract better professionals to teach. The bar can only be raised if the institution’s vision and management invest in this. Only a few institutions have managed to achieve it.

The current regulatory framework is yet to help in this. Regulations impose stiff norms and inadequately recognise professionals who teach on flexible terms as full faculty equivalents. This discourages healthy recruitment and impacts the economics of education. CoA, at the least, must enable flexible terms for recruitment and extensively encourage industry experts to teach. Despite all these changes, there can still be a mixed bag of institutions. But that is a manageable problem. The objective is to increase the average quality and not just produce a few centres of excellence.

The CoA can also be more proactive and supportive in building institutional capacity. A national-level mentoring programme must be put in place. It can create a resource-sharing network to enhance capacity by roping in institutions with resources and capacity. This can be achieved through a combination of grant-making and incentives to both mentoring and mentee colleges. Our analysis of the CoA budget from the data published for 2022-23 shows that their annual revenue is about Rs. 25 crore, and their recurring expenses are about Rs. 7 crore. A part of the surplus (Rs. 18 cr) can be dedicated to mentoring institutes.[3] Furthermore, CoA can pursue the proposed National Research Foundation, which has an outlay of Rs. 50,000 crore (2023-28), and seek a part of the grant for architectural education and research projects.

Economics of Education

A critical but less discussed factor that has led to the closure of colleges is the mismatch between the fee collected and the cost of running a B.Arch programme. Most institutions offering architecture programs are private institutions dependent on fees to meet operational expenses. Some colleges, particularly private universities, have the advantage of fixing their fees and meeting operational expenses. At the same time, colleges affiliated with a government university are bound by state-level fee regulatory authorities that prescribe fees. For instance, institutes such as the Manipal School of Architecture, charge as much as Rs. 4.16 lakh a year.[4] Symbiosis Nagpur Rs. 4.24 Lakhs[5] ; SRM Institute of Science and Technology Chennai charges Rs. 2.75 Lakhs[6] Not all colleges can charge fees at this level. For many colleges, the state fixes fees through the Fee Regulatory Authority, and it can be crushingly low. For instance, at Vaishnavi School of Architecture and Planning in Hyderabad and a few others in the state, the government has fixed fees at Rs. 75,000 per annum[7] Fee Regulating Authority in Maharashtra has fixed Rs 95,000 annually for the Vasantdada Patil Pratishthan’s Manohar Phalke College of Architecture.[8]

What is the cost of imparting quality architectural education, and how do we know whether the fee is adequate? One way to find out is to examine how the state funds their colleges, particularly the centrally funded Schools of Planning and Architecture (SPA). The assumption is SPAs offer reasonably good quality, and fees are closer to what it would cost to achieve it since they do not plan to generate profits or surplus. We know from the National Institute Ranking Framework (NIRF) records [9] that in 2020-21, the average annual cost of architectural education at SPA Delhi was Rs. 6 Lakhs. If SPA invests Rs 6 lakhs per year per student, how do colleges that charge less manage? They probably manage through higher student intake. In such a situation, a drop in enrolment beyond 15 to 25 per cent would put a financial strain, and a continued drop in enrolment would lead to closure.

The fee-based revenue model is precarious. As the costs increase, fees need to be increased. The ever-increasing regulations add to the burden, which also increases the cost. Increasing the fee beyond a point will make architectural education less affordable and less attractive. This can only be managed if grants, corpus funds, or other means support institutions.

The problem is not only fees; salaries for architects are also crushingly low. Fresh graduates’ pay is as low as Rs. 15,000 per month. If educating an architect costs about Rs 35 to 40 lakhs, including fees and other expenses, a low entry-level salary makes architecture less attractive. Practising architects are unwilling to pay higher, citing lower fees they receive, but they are rendering the whole discipline unviable. Professionals must value their work better and support fresh graduates with reasonable pay and working conditions. For its part, the CoA must get an empirically sound understanding of the economics of education and profession and review its approach. Reforms are imperative and urgent.

References

- https://www.knightfrank.co.in/research/skilled-employment-in-construction-sector-in-india-2023-10450.aspx. (Last accessed Dec 2023)

- https://www.coa.gov.in/app/myauth/notification/COA%20Perspective%20Plan%20for%20Growth%20of%20Architectural%20Education%20(Amended)-rev_11zon%20(1).pdf (Last accessed Dec 2023)

- (https://coa.gov.in/app/myauth/report/Annual%20report%2022-23%20gazetted.pdf Last accessed on Dec 2023)

- (https://manipal.edu/content/dam/manipal/mu/documents/Admissions/adm2023/2023_MAHE_Manipal_General_Category_Program_Fees.pdf. Last accessed December 2023)

- (https://www.sspad.edu.in/pdf/Revised_SSPAD_Nag_2nd_&_Subsequesnt_year_fee_approval_0002_0001_(1)_2023.pdf. Last accessed December 2023)

- (https://www.srmist.edu.in/program/b-arch-bachelor-of-architecture . Last Accessed December 2023)

- (https://www.vaishnavi.ac.in/hyderabad/fees. Last accessed December 2023)

- (https://ay23-24.mahafraportal.org/ssi_prp_22/outer.php?q=fee_search_report. Last accessed December 2023)

- (https://ay23-24.mahafraportal.org/ssi_prp_22/outer.php?q=fee_search_report. Last accessed December 2023)

AUTHORS

A. Srivathsan currently heads the Centre for Research on Architecture and Urbanism at CEPT University. Previously, he was the Academic Director of CEPT, worked as a senior journalist, and taught for a decade in Chennai. His research and writings include themes of Indian cities and contemporary architectural practices. His publications include the co-authored paper titled The long-arc history of Chennai’s unaffordable housing’ and the co-edited book titledThe Contemporary Hindu Temple- Fragments for a History.’

Chirayu Bhatt is a seasoned academic administrator and urbanist. He serves as Professor and Deputy Provost (Academics) at CEPT University, where he set up the Teaching and Learning Centre and led the transition to online learning during COVID91. He has worked at the confluence of urban planning, urban design, and public policy on many projects in the USA, the Middle East and Asia Pacific. He completed the one-year Accelerated General Management Program from the IIMA. He holds a Master’s Degree in City and Regional Planning from Georgia Tech and a Bachelor in Architecture from CEPT.

10 Responses

Good to read through such an insightful and research based writeup of an architectural education plague of sorts. This article could be the start of many more dialogues that ALive has with academicians and professionals in our field. We need more commentary on this subject

This is a good analysis of what ails architectural education and educational institutions, essentially an insiders view. But there is a passing reference to the problem that outsiders perceive – the poor salaries that architects get. Architecture has become a very unattractive profession, however noble and creative it might be.

Thanks for this incisive eye opener study. We see many distressed fresh graduates who say their choice of architecture for career was wrong. Many have left their fields and opted for careers in IT and banking by reskilling themselves. This is a serious waste of talent and resources. Indeed, reforms are imperative and urgent.

– Prakash Almeida

Srivathsan and Chirayu,

The article has great ideas on how to improve the architectural education. The pay disparity is also highlighted quite well. Your thoughts on improvement in curriculum and it’s delivery to enhance quality of education are quite applicative. Yet the research presented in the article is quite pretentious since the data analysis could lead to just the explanation of dwindling number of students and architecture colleges. Therefore the questions are not very clear. In absence of clarity on questions the criticism to CoA perspective plan is misplaced since the perspective plan intended to bring regional parity in availability of education centers. Perspective plan enacted the geopolitics of architecture education rather than enhancement of quality. Since the questions were not clear your suggestions to improve the quality appeared more of a hunch. Several example from architecture colleges were cited to support fee insufficiency and employability of students, even SPA was proved but nothing said about CEPT. In absence of wider sample and non existent methods, the research appears to be a promotion to CEPT way of education (which is very relevant and I support it) rather than making suggestions from an introspection.

1. Change name of CoA to Indian Council of Architecture

2. Open Architecture Depts in every municipality and employ Dip. Arch and B. Arch graduates for building plan scrutiny

3. Run awareness campaign on national TV about benefits of taking guidance of an architect for any Building project

4. Civil Engineering deals with Design -Approval-Construction of All types of Civil Works (roads, dams, tunnels, canals, bridges, culverts)

Architecture deals with Design -Approval-Construction of all types of Building Works (houses, stadiums, bus stands, hospitals, offices, schools..)

Show thie above difference to Indian Citizens by comparing syllabus of B.E. or B.Tech(Civil) and B.Arch. If possible remove building structures from civil engineering studies which they generally learn for just 1 sem. Whereas architects are learning buildings for 10 semesters. See the difference subsequently.

5. Hold primetime TV debates about role of architects

6. Provide service protection to teaching and practicing architects from denied or delayed payments

7. Create Working opportunities for architects in Urban Development Authorities

8. Put the executive committee of CoA on full-time payroll position during tenure

9. Set tracker for IIA for local activism

10. Make live projects in architecture colleges compulsory as part of curriculum

Ultimately the profession should benefit the people. Architecture has become totally fanciful in our society.Architectural design should be made more scientific in approach catering to the needs of the people. General public are scared to approach architects due to show and fees.

Ar. Srivathsan and Ar. Chirayu,

Appreciate the effort taken to gather the data and analyze it. I wish to add on some points.

1) In the last 1 month we visited around 50 plus PUC 2 colleges for promotional activity. The awareness of Architecture course and profession of architect is very low in a class of 60 on an average 2 to 4 students know about architect and the profession. We need to run awareness campaigns.

2) The qualifying exam NATA and JEE-2 is another glitch. not many know about it we get calls they want to join architecture but they have not appeared for NATA or any other qualifying exam. COA has to work on this, how to make it more accessible. From the day of its inception in 2006 till date it has never stabilized every year there is a change. The fees charged is also very high, students from smaller towns cannot afford it. Students who passed diploma Arch should be exempted from aptitude/qualifying test, for 3 years they have studied it. lateral entry should be allowed for diploma students.

3) In the practice and profession the signature of an architect must have some value as in other professions like CA’s, Lawyer’s, etc. the document is invalid without the signature of the respective professional.

4) I come from the era in which almost 80% of my mentors used to be practicing, visiting architects. same needs to be brought back. The mandate of number of full time faculties has to be reduced there needs to be more practicing architects mentoring the students.

5) My alternate proposal is that a candidate seeking to become an architect, should first join an architects office and start working. Each architect should be authorized to enroll a fixed number students every year to an architecture school. of the 6 days 3 days to be spent in office and 3 days for learning theory subjects and writing exams at architecture schools to get the required credits to graduate as an architect. The enrolling architect should get a fixed incentive from the schools based on the number of students enrolled by the respective architect.

I think it will be good Kickstart for the student persuing the architecture. And to validate themselves into the career.

Appreciate the effort and hardwork put towards the development of Architecture ferternity. Great applaude to both the professors.

1. It seems like you have valid concerns about the accessibility and stability of the NATA and JEE-2 qualifying exams for architecture. Your suggestions, such as exempting students who have completed a diploma in Architecture from aptitude/qualifying tests and allowing lateral entry, could be valuable improvements. Advocating for these changes through constructive feedback to the Council of Architecture (COA) or relevant authorities may help address these issues and make the process more inclusive.

2. Need awareness about the Qualification exam to pursue Architecture

3. We need to analyse about the multiple exit policy (NEP). 3rd year as Bsc, 4th Yr as B.Tech and 5th Yr as B.Arch

4. The signature of an architect holds significant value in the practice and profession. It serves as a mark of accountability, expertise, and authorization. Similar to other professions like Chartered Accountants (CA) and Lawyers, an architect’s signature on a document indicates their professional endorsement and renders the document valid within the context of architecture and building-related matters. This signature often signifies that the architect has reviewed, approved, or is responsible for the content of the document.

5. Need to give awareness and ehnace the opportunity available in the employability factor. Especially in government sector. Each municipality need on architect.

This is a very well written writeup with lot of study and awareness of latest developments in the field of Architecture. Being an Architect myself i can relate to the facts mentioned in the article. In profession like architecture one can not and should not spend 35-40 lakhs a year as the earning in not high. Tapping into the National scheme is a good idea. Also, while i do have concerns about the quality level of an undergraduate at 3 years but it is working very well in Europe so maybe its time we give it a shot too. Reducing credit courses will definately improve the time spent on mandatory and necessary courses elevating the quality of under graduate.