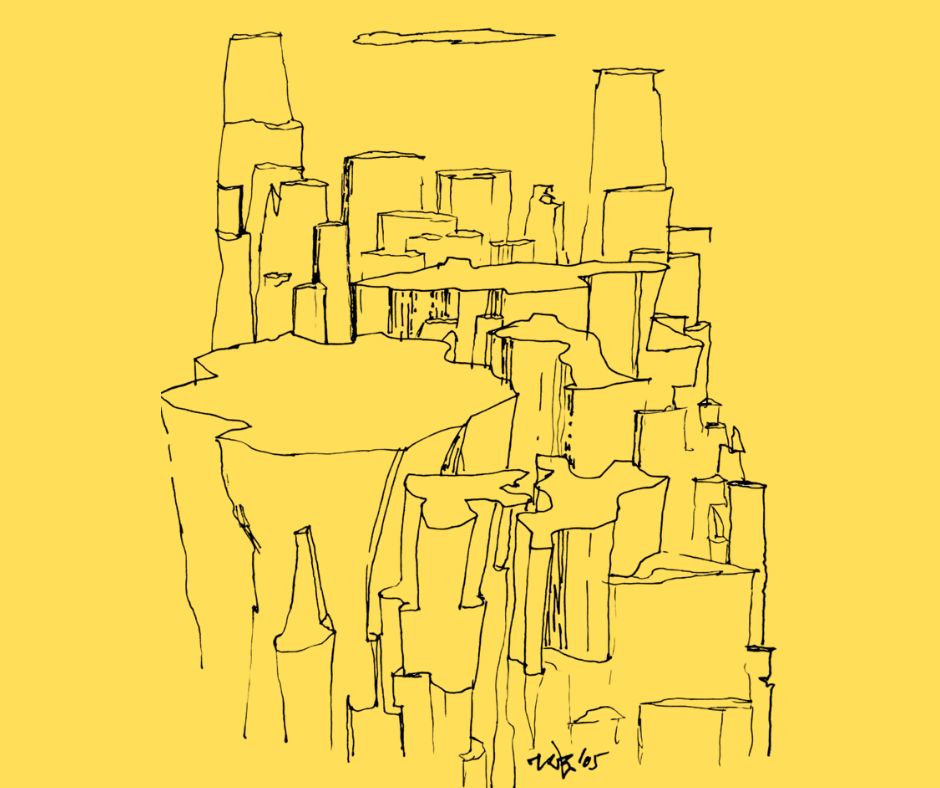

Much has been said about ITPO’s decision to raze the iconic Hall of Nations in Pragati Maidan, before as well as after the fateful 23rd of April; there has been shock, disbelief, disapproval, outrage, and grief, but there has also been acceptance and even apathy. We met with eminent Indian architect Raj Rewal to talk about the erstwhile landmark – often regarded his magnum opus – in an attempt to learn more about this structure, and the significance and symbolism associated with it.

When asked about what one can do in times such as this – when the actions of government bodies in the urban environs become impervious to public opinion that inhabit these spaces – he raised a pertinent point about the need to make concerted, diligent efforts to protect and preserve built icons of our city. “Architects should take the lead,” he said, when asked what could be done to channel this dismay to constructive ends, “we can create a lobby which collects and collates these ideas and grievances, and we should involve the general public as well; these collective feelings should be made heard, maybe given the form of a demonstration or a peaceful protest.”

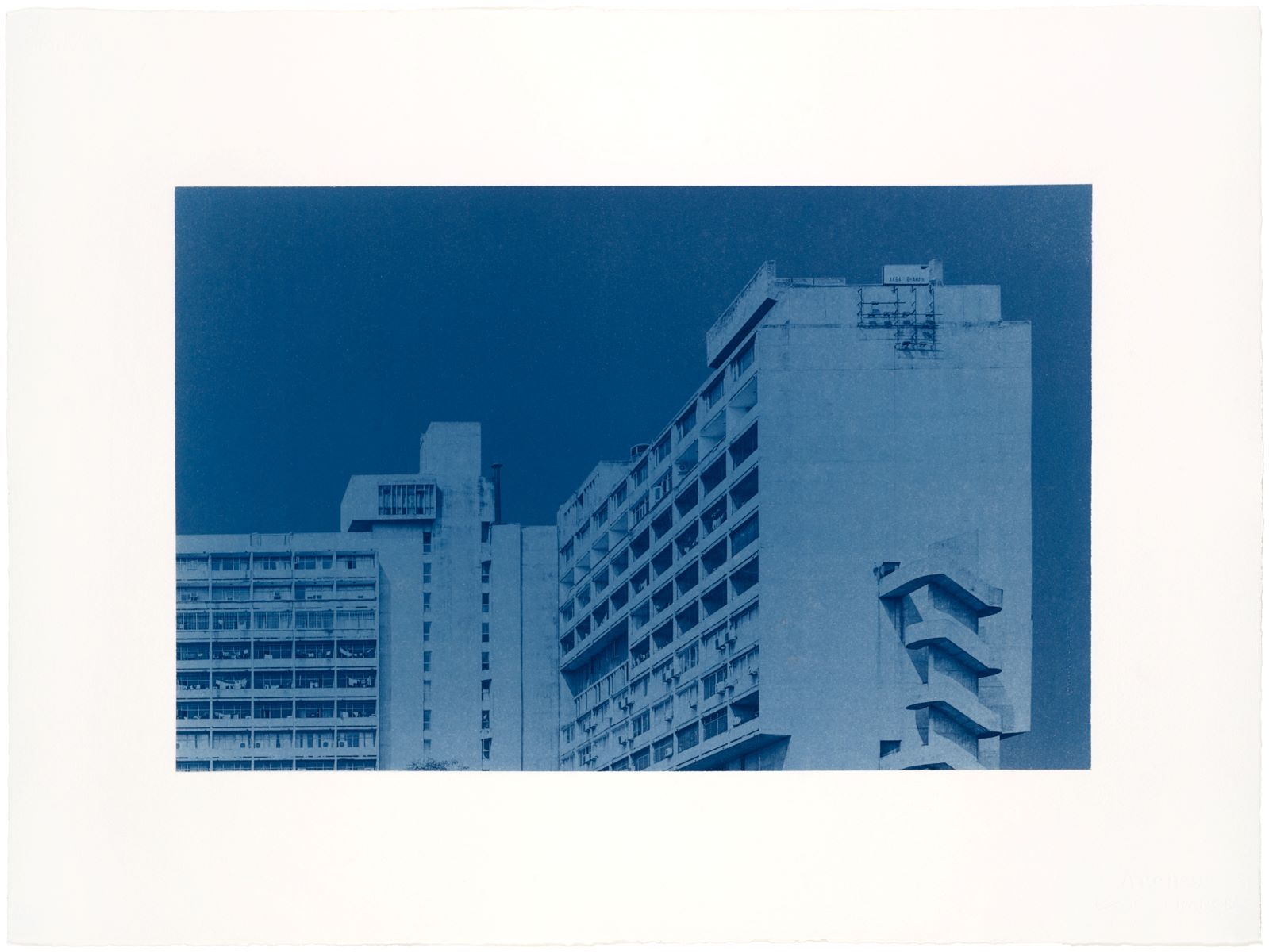

The exhibition complex had been built to commemorate 25 years of the country’s independence, and had provided ample space and natural light for large-scale events

He further expounds on how restitution is in order, as well – as much to conserve an icon, as to set an example, “It should be reconstituted, ideally at the same spot. We can do it by today’s means, and add to it as needed. As we know, the new design is earmarked at 2500 crore rupees; 100 crore rupees is enough to rebuild just the Hall of Nations, and the total complex would not cost more than 250 crores, in my opinion.”

“The design can be revamped, with air conditioning and all… I think this part at least should be rebuilt, if not there then somewhere else. Of course there will be divergent views about it – even I have reservations about it, it would be difficult to build this again – but it can be, and it should be, to ensure that it’s not wiped out totally.”

The idea of reconstitution of the structure finds resonance in a historical precedent – the one of Les Halles of Paris. Popular as the ‘belly of Paris’, this traditional fresh foods market was dismantled in 1971 after it fell into disrepair and was deemed inadequate for the city’s needs. With the market itself shifted to the suburbs, one of the glass-and-cast-iron pavilions from the original design were reinstated in Nogent-sur-Marne in memoriam. Another was reinstated in Yokohama, Japan, as an acknowledgement of the architectural significance of the original.

The demolition of the overground structure of New York’s Penn Station resulted in civil outrage which spurred the local government to pass the Landmarks Preservation Act aimed at preserving the city’s architectural character

“[Hall of Nations] was a great feat of art and architecture… it was a symbol of what very ordinary people can do. 500 families worked on the site; there were no canteens, no crèches, no helmets, and the work went on for a very long time. The structure was built from hand-poured concrete, and was labour intensive; the credit does not only belong to the architects and the engineers, but also to these people – because it was their achievement, to have created something through such simple methods.”

There indeed is merit in the idea of reconstitution of the original; it can not only retrieve a symbol of Indian architectural excellence and technological self-sufficiency during an important period in our post-colonial history, but also – in light of recent events – become a statement of adaptability juxtaposed with resilience, of a will to preserve the best of what our past has to offer, even when the transient institutions of power fail to back it up. A reconstitution of the Hall of Nations could very well become an example of the people taking charge of their own urban habitats, and deciding by conscientious consensus what should be preserved for posterity. It is a daunting cause and an immense responsibility, but the collective cultural identity of a people is defined precisely by such initiatives.

“Personally, I think the Indian political institutions are architecturally illiterate.” notes Ar. Rewal, emphasizing the need for the community to take a stand against the actions of these transient forces, “Whether the motivation [behind the demolition] was political, or bureaucratic, or financial – these are questions that remain to be asked – it’s clear that the administrative establishments are philistines. Whether we consider the present government or the one before – it’s a question of good architecture and how to preserve it, and they may be good at doing what they do, but on this aspect they have no clue.”

Given the socio-political significance of the structure, it had been suggested that the Hall of Nations be retained in the new redevelopment scheme, and renovated and retrofitted as need be

Speaking about the direct consequences of the actions of the bureaucracy, he further comments on the 60-year criteria established by the Heritage Conservation Committee, “I think it’s not only arbitrary, it’s very silly. The idea of heritage does not concern itself with only a symbolic significance, but also how important a building is to a city, from an architectural, cultural as well as artistic point of view.”

“Hall of Nations was celebrated as one of two of the most important buildings built in India in the last century, and it was published very widely – it was considered by most as an important part of Indian heritage, and not only by architects within the country. Museums across the world acknowledged it as a part of India’s heritage, and eventually world heritage. If a building acquires that kind of significance, it should be considered heritage, even if it is not 60 years old. The world heritage committee doesn’t have such a time-based criterion.”

“And who should decide if a building constitutes heritage?” he continues, “The present rules and regulations dictate that it should be done by a governmental committee – in this case the HCC – but I think that a heritage committee should have experts from not within the government, who toe the line, but members from within the profession, such as eminent architects, historians etc. INTACH, for example, has done very significant work by compiling the list of buildings that should be considered modern heritage.”

Other than the Hall of Nations, Hall of Industries and the Nehru Pavilion, several other prominent works by Ar. Rewal featured on INTACH’s list

The issue, almost inevitably, devolves to the role of architects in the modern society – of the position they hold and the powers they wield, or don’t. This tussle of retaining relevance in a rapidly evolving economy without having to compromise with higher ideals of art and ethics is one that has plagued the architectural community for years. In times such as this, it becomes even more important for the fraternity to assert their autonomy in a field which only admits them after stringent qualifications. “I personally think that the architectural community is very isolated,” muses Ar. Rewal, “everybody is involved in their own work. I feel that we should make the Indian Institutes of Architects a more viable organization, and the Council of Architecture should also have more eminent members.

“Economists run the economy of the country no matter who’s in power, and it’s the politicians who take their cues from them. Similarly, lawyers don’t allow anyone else to come in their sphere of influence; the judiciary doesn’t let the government affect their working.”

“Ideally, architects should have a similar authority in their own fields.”

You can read the first part to this interview here.

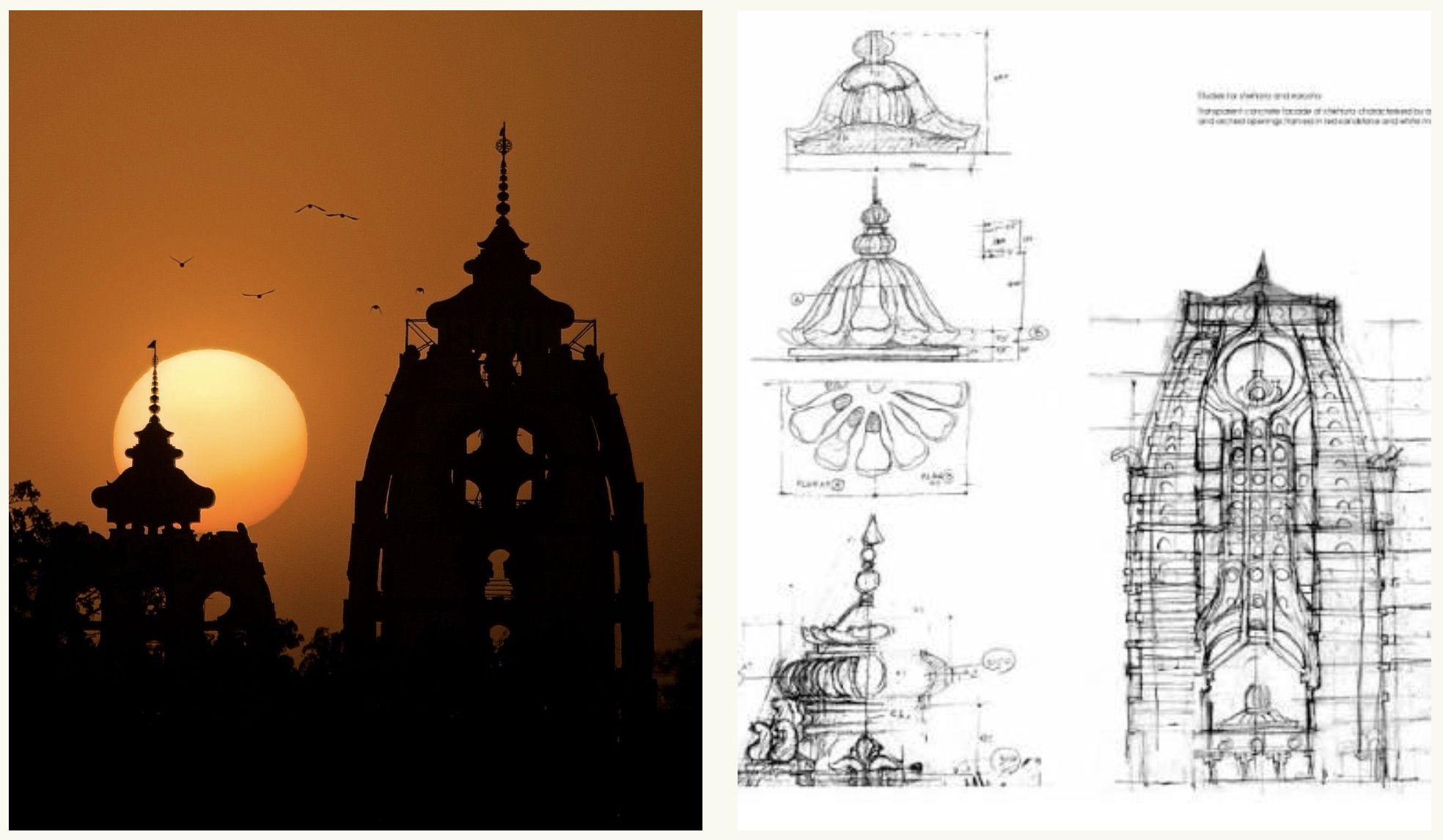

A distinguished doyen of architecture from India, Raj Rewal is recognized internationally for buildings that respond with sensitivity to the complex demands of rapid urbanization, climate and culture.Some of his creations include the Hall of Nations in Delhi, the Nehru Pavilion, Delhi, the Asian Games Village, Delhi, the Library for the Indian Parliament, the Lisbon Ismaili Centre, Portugal, the Indian Embassy in Beijing and the Visual Art University, Rohtak.

A distinguished doyen of architecture from India, Raj Rewal is recognized internationally for buildings that respond with sensitivity to the complex demands of rapid urbanization, climate and culture.Some of his creations include the Hall of Nations in Delhi, the Nehru Pavilion, Delhi, the Asian Games Village, Delhi, the Library for the Indian Parliament, the Lisbon Ismaili Centre, Portugal, the Indian Embassy in Beijing and the Visual Art University, Rohtak.

Rewal has received many honours, including the gold medal for the Indian Institute of Architects, the Robert Mathew award from the Commonwealth Association of Architects and Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres award from the French Government.

His works have been exhibited at the National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi and the Pompidou Museum, Paris.