Charles Correa firmly believed that architecture and urban design were instruments for social change. A tribute by Durganand Balsavar.

Charles Correa had the rare ability to combine pragmatic complexity with wit and humour — not only in his writings, but also in his architecture. The architect who passed away recently was widely recognised as one of the most distinguished architects of our times, the visionary revered the notion of ‘open-to-sky’ spaces — be it the courtyard, the kund (tank), or the chattris (umbrellas) on the open terrace. With a scholarly understanding of politics and history, Correa engaged fearlessly with the polemics of the city, urban space and architecture. The quintessential Renaissance architect was an activist, urbanist, theoretician and thinker, engaged in an impatient yet rigorous search. In a distinguished career spanning over five decades, Correa believed that architecture and urban design were instruments for social change. Charles Correa, B. V. Doshi, Raj Rewal, Raje, Stein and Kanvinde, each charted a new trajectory in architecture. It’s no wonder that Correa received a gamut of national and international awards, including the Padma Vibhushan.

Setting up his practice in 1958 after returning from MIT, a young Correa was assigned to design the Gandhi Smarak in Ahmedabad. In the early years of Independence, the nation was discovering its own destiny with the Socialist credo — ‘simple living, high thinking’. In response, he designed with a rare simplicity, deploying exposed bricks, clay tiles, exposed concrete and wooden louvers. It was a combination of square modules, carefully proportioned and placed at a reverential distance from Gandhiji’s ashram. An inclusive and egalitarian space, the Gandhi Memorial is open to village communities and urbanites, making no distinction between them.

Correa had the ability to convey his ideas with simplicity, but beneath the veneers resided layers of complexity and a questioning mind.

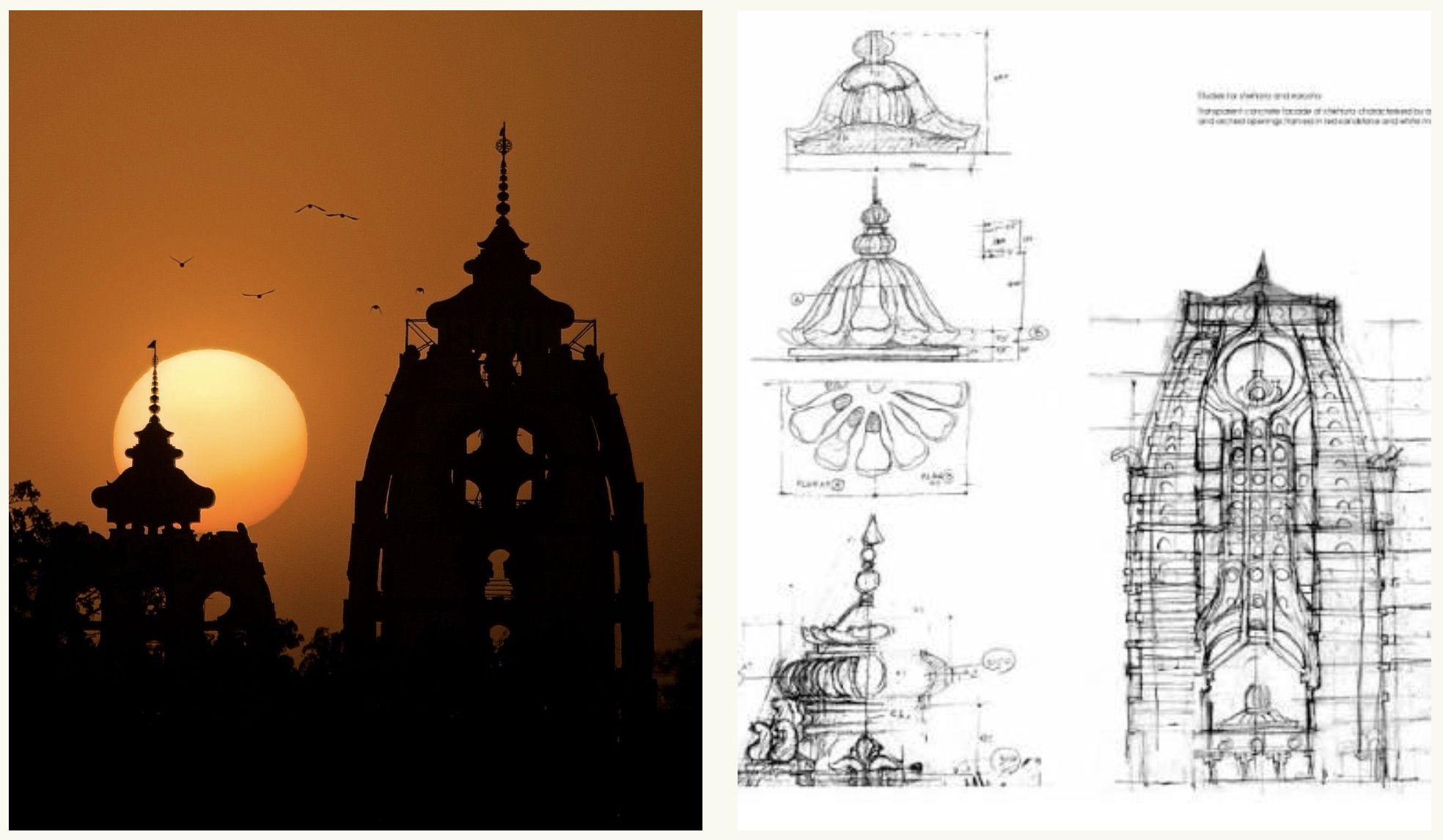

Jawahar Kala Kendra, Jaipur

With each project, Correa had begun excavation of the principles in history. “We cannot comically imitate history,” he would impatiently remark, “History is a profound repository of space and time. It is the abstract principles we discover in history that we imbibe and learn from.”

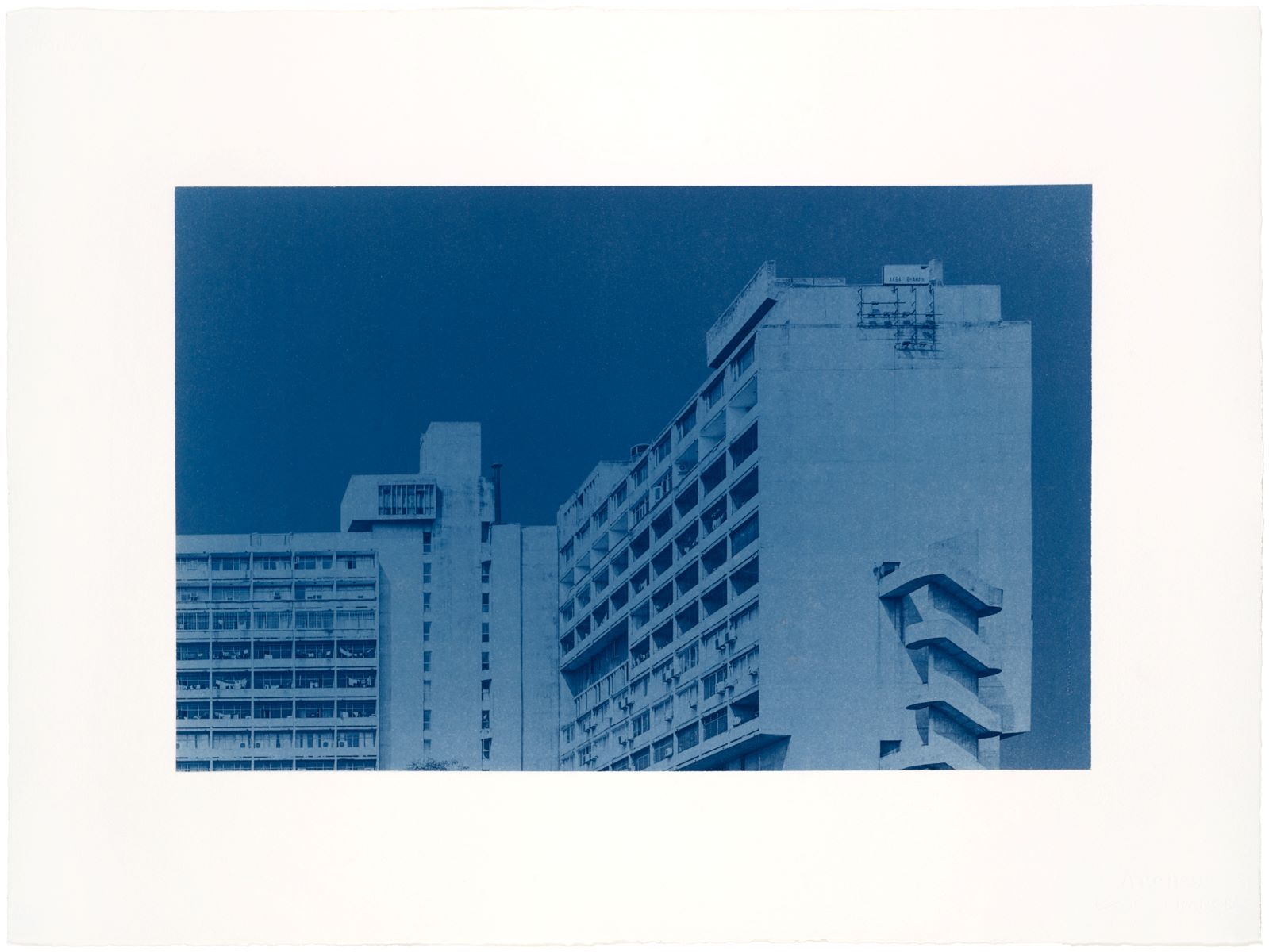

The stark exposed concrete of Le Corbusier in Chandigarh (1955) and Louis Kahn in Ahmedabad (1962) echoed a universal emancipatory tone. It was stoic and monastic. However, it did not respond to the diversity of expressions of an energetic new nation and its people.

Along with B. V. Doshi and Raj Rewal, Correa embarked on a process of imbibing memories of the past, while paradoxically looking into the future. Indian cities and the precincts of the past became the new references — Fatehpur Sikri, old Goa, Madgaon, Padmanabhapuram, the towns of Rajasthan, Thanjavur, Srirangam, Hampi, Agra, and Vijayanagara.

The pristine forms disintegrated, to allow the expression of fragmented mass, introverted courtyards open-to-sky, cascading steps, pergolas, vernacular colours, verandahs, natural light, shade and breeze, with informal spaces for gatherings. When Correa was commissioned to design the Jawahar Kala Kendra, an art and cultural centre in Jaipur, it was a project to express this vibrant juxtaposition of history and the promise of the future. Correa had been fascinated with the skies and the cosmos, similar to Sawai Jaisingh (18th Century), who had been provoked to build these gigantic instruments — Jantar Mantar to probe the skies. Despite its contradictions, Correa designed the plan of Jawahar Kala Kendra based on the nine-square Jaipur mandala representing the celestial mythical deities of the Navagraha. Correa’s project consists of nine squares with a corner square displaced, echoing the plan of the city.

A spirit of experimentation, allowed an organic union of colourful wall murals, collaborating with artists in the creation of space. The ‘awakened walls’ transformed the experience, bringing in a metaphorical interpretation through images.

Kala Kendra, Goa

The paintings of Chirico, sketches of the legendary Mario Miranda, in Kala Kendra (Goa) lend an illusory depth to plastered blank walls. The collaboration with artist Howard Hodgkin for the British Council in New Delhi created a surreal experience of the shadows of a tree symbolising India.

The culmination of this stage of experience was the Salt Lake City Centre at Kolkata, where the architect inverted conventional notions on their head with a vast expanse of steps and open-to-sky spaces. This is probably one of the most successful constructed public spaces in contemporary times.

Correa’s last three off-shore projects were the McGovern Institute of Brain Research (MIT), the Ismaili Centre (Toronto) and the Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown (Lisbon). This centre was an incredible, symbolic gesture for humanity’s quest to discover new frontiers.

Correa’s incredible oeuvre is more relevant than ever before, given the fact that millions continue to migrate to our cities, in search of a new beginning.

This article was first published as ‘A fascination with the sky’ in The Hindu on 17 November 2021.