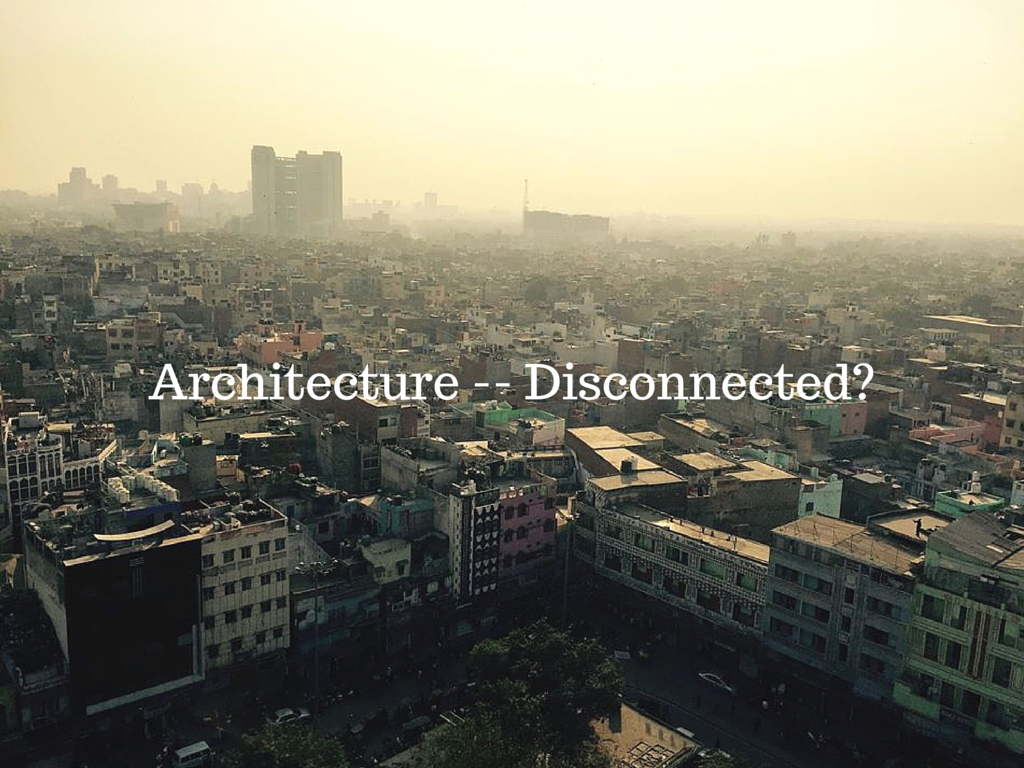

Third in the series of ‘Architecture — Disconnected?’ – Thoughts by architects and educators in India, on the relevance of architecture today in the society.. Suprio Bhattacharjee talks about where has the profession failed..

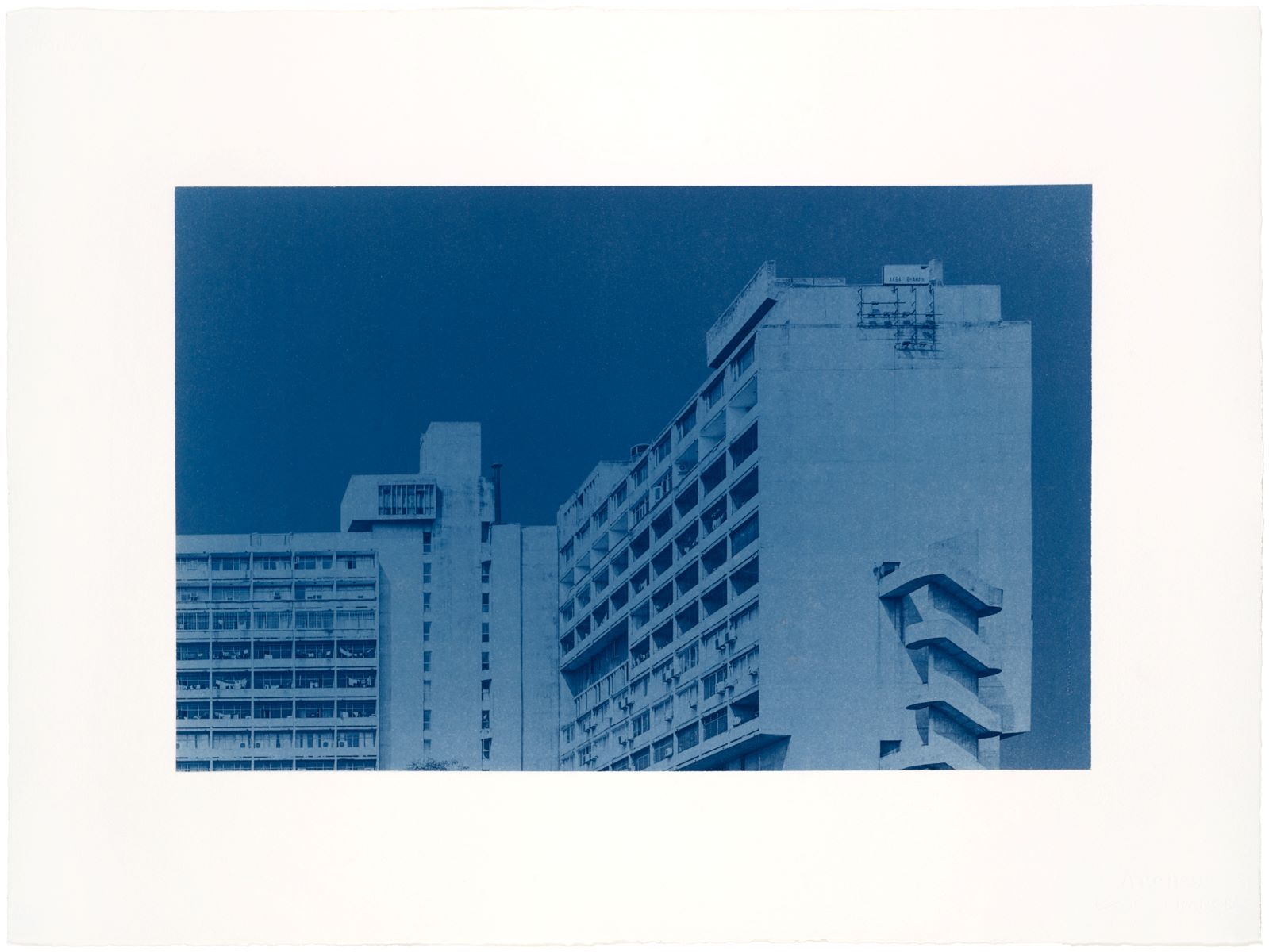

If we restrict our geography to India, the answer would be a resounding yes. Currently we exist in a crisis of production, as not only are we building less and less (if at all) for the people, the projects that are indeed supposed to be public in nature are being built without true public participation – for instance there are almost no open design competitions that value design merit over turnover-measured competence. And most of the funding dynamics are also such that the Government itself spends less, and instead there is a reliance (pun intended) on private capital. The moment the Government abdicates its role and responsibility as a provider for spaces and (places) for people, architecture for the public good dies right there – and instead is absorbed into the capitalist game of architecture for profit. And thus the much celebrated new ‘museum’ in Mumbai is not a freely accessible public building, but the arrivals and departure lounges of the city’s fancy new airport – the Terminal 2 as it is called – where an exploding economy allows for the polarisation of wealth to create a new class of people who can afford air travel – a new elite – for whom these works of art are no different than a temporary visual relief from the monotony and drudgery of a large building with an endless repetition of modular spatial and structural bays. Thus the art becomes less an appreciation of craft, technique and intellectual engagement, and becomes akin to a billboard or advertisement professing the airport to be more than what it really is – an airport. In most cases – the artworks – many of which are of a grand scale and as works in themselves extremely meticulously crafted – are barely visible or readable in their entirety – placed awkwardly in light wells and inaccessible or placed along travelators where one is unable to appreciate the work itself as there is no opportunity for pause and reflection. So the building takes us back to the museum-as-cabinet-of -curiosities – although here for the paying air traveller – and to be seen as glimpses of ‘an exotic India’.

But if we investigate this death of the public building and thus the absence of an architecture-for-all, one realises, that architecture in the independent country rarely ever had a public or social agenda. Our most celebrated public buildings are still the ones that were built by the British, and in sporadic incidents, rare flashes of exalting public architecture in the few decades after independence. Our railway stations, other than the stupendous creations that were the (British-built) terminal buildings such as those in Chennai, Kolkata or Mumbai – were mostly utilitarian sheds, devoid of even the most basic necessities or facilities. As such they were not even utilitarian. And oh, since they are meant to serve the poor masses, as such, they were deemed just enough. There is no dignity in poverty, no dignity in the remote, no dignity in the rural.

Our schools – supposedly public buildings that shape the early years of an individual – are no different. The grandest school buildings are still the ones that the British built (and thus are fetishized by film-makers) – most of which are convents and run by missionaries – while the administration run schools are none other than strictly functional containers meant to execute their specific instructional aims. A school building can be transformative, as can the exposure to public space. Today public space is controlled and rationed – in Mumbai available only for a few hours in the wee hours of the morning and a few hours in the evening (the municipal gardens are shut during the day) – and thus only the new elites in gated residential communities have 24×7 access to parks and gardens within their confined surrounds – a privilege that comes at a hefty price. Perhaps there is a collusion to wrench public space out of the purview of being a right – that it is supposed to be – such that it can be absorbed by market economics into a commodity – to be sold at a premium. Haves and Have-nots of public space. Even in the other great outpost of capitalism – the United States, there is a dedicated focus on the creation of public parks – and thus a healthy and evolved discipline of urban landscapes – however here even this is an elitist commodity.

Thus of course architecture in India serves today only the economic elite. And with an administration that is increasingly tilted towards private capital, without adequate safeguards to protect the interests of the people – one can only assume the situation will worsen.

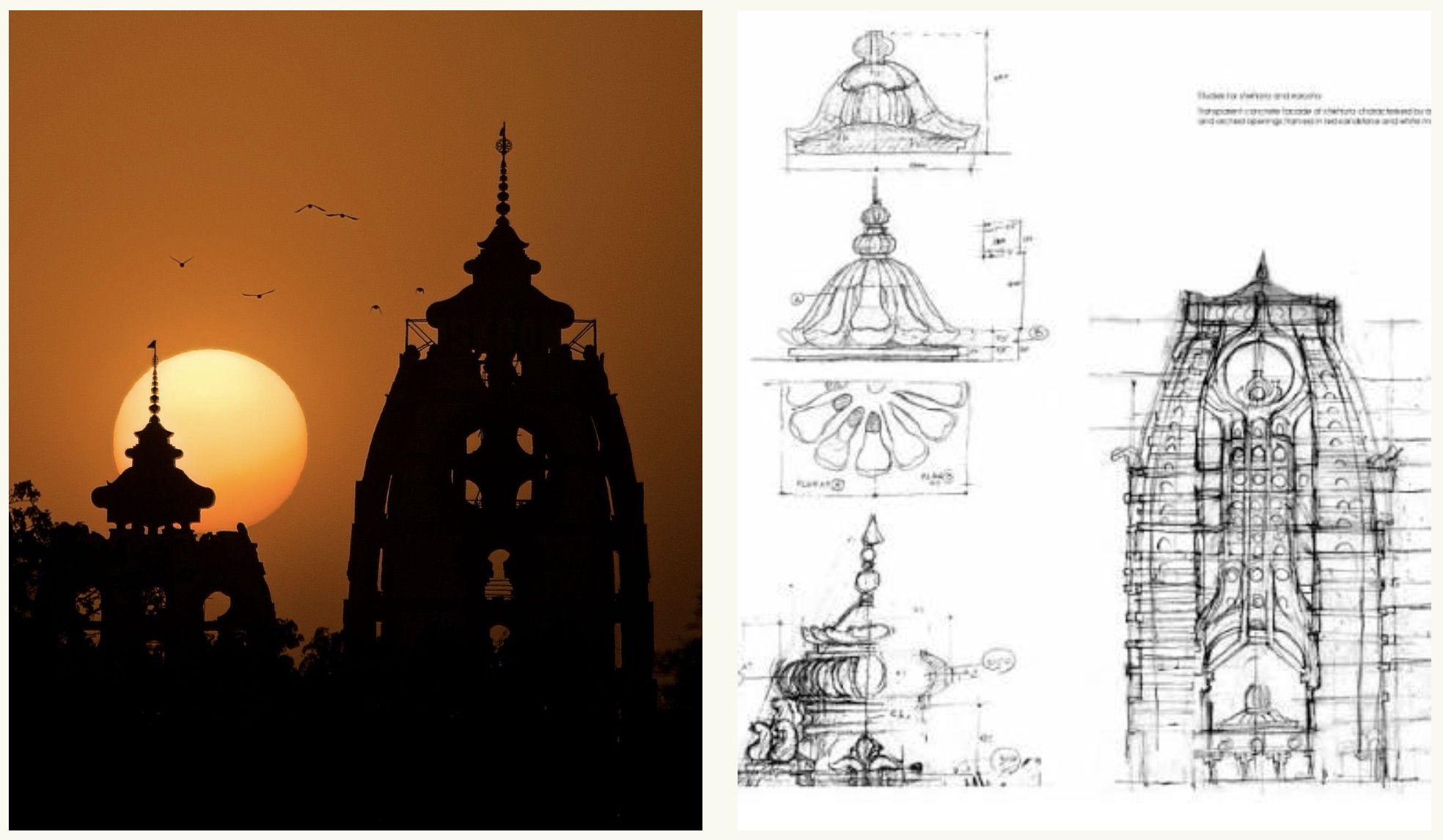

Are practitioners to blame? Yes of course. As are our institutions. Our architecture schools – that have not developed a culture of inquiry and building for the public good. Architecture is still seen in most schools as an esoteric activity – far removed from the reality of our situations, and in schools exercised as fancied escapades from the challenge of responding ingeniously to the harsh realities around us. As much for the faculty for whom this becomes either a joyride into the realms of the fantastical – although purportedly sold to the students as ‘real’ – and perhaps projections of a reality – or they otherwise become banal excursions into the ‘so-called-practical’ and thus sold as another version of a reality . As such unless there is an ardent and urgent inquiry into what kind of urban or spatial future we would like to have for ourselves, our schools of architecture will continue to produce professionals who have no faith and willingness in reinstating the public back into the centre of discourse and architectural production. Maybe everyone should be reading Henri Lefebvre. But that too is a distant dream, considering the lack of intellectual enquiry in our schools.

Suprio is a Principal Architect and Founder of award winning firm – S|BAU

Suprio is a Principal Architect and Founder of award winning firm – S|BAU

In addition to architectural practice, he is deeply involved into Independent Writing & Research. He is a guest writer at DOMUS India Magazine and Professor of Architectural Design, Theory and History at Rizvi College of Architecture, Mumbai.

6 Responses

Architect Prof. . Suprio jee A very absorbing relevant article. With you all the way. It is it just India but all over the Globe. But I still see a spark. It will ignite Ar

Nd set lives ablaze. But time must bide.

This auto spell check is like today s architecture. It intervenes with no sense of comprehension. Makes one look like an idiot.

Mass production is crass production, whether professional or academic. The sense of enquiry, practicality, affordability, and innovation in thinking with materials and structure has rarely been part of educational institutions. These qualities were and are restricted to individuals. The economic elite doesn’t want any of these qualities.

Our architectural education is also to blame.is there an exercise in any part of five years to build a hutments for under priveleged sections a part of design Studio.or was it a part of syllabus.a poor man with simple needs does not become a client in school days.students who are future architects are not sensitised to this issue.prof.suprio a good thought provoking article

Architecture (historical) has always served the point of power and even now its doing the same (and may be also in the future), it is high time we should start accepting this. India is not a Socialist economy hence excepting a truly socialist project of architecture is like living is a fake dream. I do not think architects or architecture education is to be blamed for this because they are not the once who call the shots and frankly we are just a very tiny (not so relevant) part of the larger system, Architects are used to thinking of themselves as game changers and much being relevant then what they actually are and such romanticised ideas about ” the Social , the Public ” are never accepted as a outcome of a capitalist regime but thought of as a primary agenda (which it never is) only once we start accepting this is when architecture scene of India would have a critical and important opinion.

And about being “sensitive”, we talk about this a lot but what being sensitive achieves are solutions which are super subjective and work on certain established premise (which is not a bad thing) but i think rather than being sensitive what architects and student should be encouraged is to be critical.

Agree. Architects have almost no role to play when the client decides to have his way. Architects only serve their clients. If a client wants a private building, the architect will design private building. Architect works to efficiently achieve clients objectives. Architect cant change clients objectives.