Remember the campaign – Architecture Disconnected, where we talked about how architectural profession today is totally disconnected and doesn’t really serve the society? The above campaign kicked off with a short note by Swati Janu, where she said,

Within India, a staggering 95% of the population does not have access to designers or cannot afford design.

We architects need to rethink how we can be relevant to our society. This requires thinking outside the silos of our professions and collaborating with other disciplines ranging from urban development, economics to sociology.

(CLICK HERE to read more views from architects on the state of the profession today in India.)

In this post we present the ModSkool, where Swati Janu and Nidhi Sohane worked closely with the community and helped locals with not only building their own school, but also raise the required funds.

Context:

Yamuna Khadar is a settlement of farmers by the floodplains of the river Yamuna in Delhi. It is a rural community nestled within the city but set away from the rest of it, connected only by a dirt road to the nearest main road. For a farmer there, public transport is neither accessible nor affordable, and they have either cycles or just their feet serving the last mile.

Since 1993, a school by the name of Van Phool has been educating young children and serving as a crucial bridge to a formal education system which they can’t access till they are old enough to travel to the nearest secondary school on their own. In 2011, DDA razed the entire settlement due to its ‘illegal’ status, leaving a pile of rubble in place of the school which used to run out of an old brick building. The school had since been operating under a temporary shelter made of tarpaulin sheets pulled over a thin bamboo framework.

On filing a PIL, the community representatives obtained permission to rebuild the school as long as it was ‘temporary’. This led to the evolution of a design brief for the two architects who decided to take up the project to build a school that could be dismantled in order to protect it from demolitions, ensuring its existence on the fringes of legality. The brief was carved out of the urban and political setting of the place, which required it to provide a protected space conducive to learning while fulfilling the legal criteria of how temporary or permanent it was allowed to be. At the same time, it needed to be affordable, easy to maintain and develop as a part of the community for them to take ownership of the space.

ModSkool emerged out of this need to provide for a community that survives with tenacity in a place they are not allowed to. It is also representative of a space that asserts the rights of a community to sustain and grow. ‘Van Phool’, the name was coined by the school’s Founder G.S. Labana to symbolise how a wildflower often manages to grow even in a hostile environment. The school, then, needed to be a sight of beauty and respite, growing in and despite hostile conditions.

Design Approach:

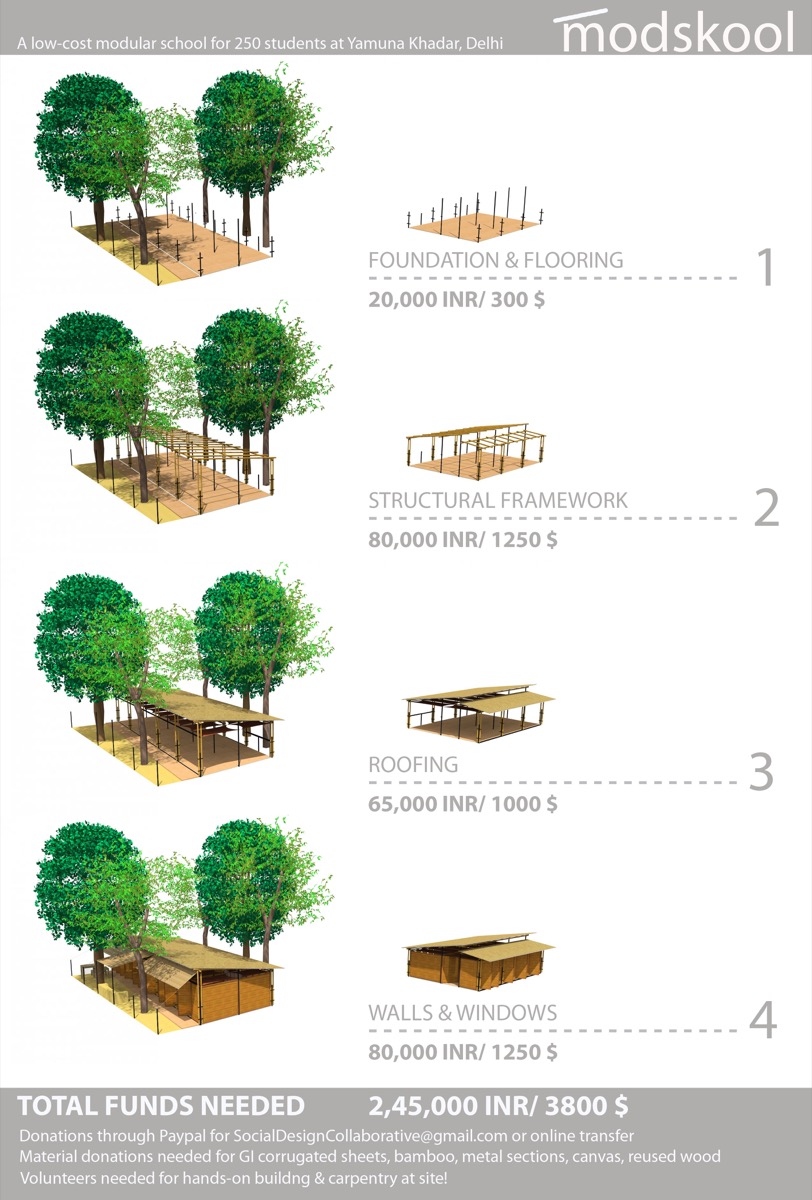

There are two facets to the design approach taken over a period that spanned almost two years. One is the design of the physical space that architects typically take up. And the second is the multitude of things, small and big, that went on to make the project, encompassing project management, fundraising, community mobilisation and site management. The architects took up the project on a voluntary basis due to its socio-economic context. During the course of the interactions with the community over a year, they realised that they also needed to take up fund-raising since the community was unable to raise adequate funds. Through social media and word of mouth, they were able to collect required funds from friends and family within a few weeks. They also decided to come up with a design that was DIY and could thus save the cost of labor by building it themselves and with the help of other volunteers.

A context that is as volatile and informal, as it is inaccessible, comes with the many challenges of provisioning for even basic infrastructure at site from food and water for the builders to fuel for operating power tools. The process of construction was fraught with limitations such as the cost and difficulty of transporting materials from the main road to the far removed site, absence of electricity for light and running welding and drilling tools, exposure to elements of nature and the whims of Delhi weather. Site planning, thus, became an important task for the two project architects along with coordination of volunteers who got in touch to help build the school. A large part of their work also involved community mobilisation in building, first, the trust with the local residents and only then, the physical structure of the school. It also required constant monitoring of the building process due to insecurity in the community around the definition of a ‘temporary’ structure and pacifying conflicts to do with the sensitive volatility of ownership of land. Thus, the architects found themselves transcending beyond the typical hierarchies of architecture, becoming the laborers, contractors, project managers, community mobilisers and social media promoters all at once!

Building Process and Design:

The school had to be made of temporary materials and its structure had to be designed such that it could be disassembled in a matter of a few hours. The original design had used bamboo screwed together with simple metal joints but due to the generous donation and engineering advice by Vinod Jain, Director of the engineering firm Vintech Consultants, the entire structure was built in metal sections screwed together through welded plates. The walls were built by volunteers through hands on work with reused wood for frames and bamboo mats as infill which were woven by the students themselves. This involved on-site experimentation and consultation with the local bamboo craftsman to develop the final weaving patterns. Bamboo mats that the residents bought from the local market and used to build walls of their homes were used in the school as well. Bamboo was used due to its ready availability, affordability, lightness, ease in working with as well as due to the sense of belonging it helped create for the students, being a natural material that they were used to living with. It also requires little maintenance and can be repaired or repaired easily, being locally available.

The school comprised of two blocks with 5 classrooms in all. The partitions between the classroom were made of light wooden frames with bamboo mats as infill that can be unscrewed open to create a larger hall when required. Pivoted doors and windows made of split bamboo within reused wood frames help create airy and open classrooms with adequate light and ventilation, with wax coated canvas screens inside that can be rolled down to insulate during winters.

The roofing is in decked metal sheets with local thatch on top for insulation and canvas hung below to create an insulating pocket of air flow. The school was built in a matter of three weeks with about 50 volunteers helping out. With bamboo walls that can be repaired and modified, the design of the school allows for it to change and evolve with time. The next steps for the project are to come up with ways to make the modular design of the school replicable across locations for those with similar needs for a low-cost, temporary school.

About the Architects:

Swati Janu is a 33 year old community architect and artist, who has been working to bring design to those who do not have access to it. Her architectural practice combines community art & engagement with practice based urban research on issues of migration and urban informality. She is the Creative Director at mHS CITY LAB & the co-ordinator of talks on social change called ‘Barsati’. A graduate of School of Planning & Architecture, Delhi, she also holds an MSc Sustainable Urban Development from University of Oxford, UK.

Swati Janu is a 33 year old community architect and artist, who has been working to bring design to those who do not have access to it. Her architectural practice combines community art & engagement with practice based urban research on issues of migration and urban informality. She is the Creative Director at mHS CITY LAB & the co-ordinator of talks on social change called ‘Barsati’. A graduate of School of Planning & Architecture, Delhi, she also holds an MSc Sustainable Urban Development from University of Oxford, UK.

Nidhi Sohane is a 25 year old community architect who believes in design that catalyses social change. Her interests lie in affecting urban issues through an interdisciplinary lens and creating an informed discourse around them that is accessible to the public. Project coordinator at mHS City Lab and part of the ‘Barsati’ core team, she is a graduate from School of Planning and Architecture, Delhi.

2 Responses

How to contact them

We too need such school for children of slum area.

Hello,

You can reach them on socialdesigncollaborative@gmail.com

Thank you.