Frank Gehry, one of the most influential architects whose sculptural designs redefined what was possible in modern design, died Friday. Meaghan Lloyd, Gehry’s chief of staff, confirmed his death, marking the end of an extraordinary career that spanned more than six decades.

Frank Gehry was one of the first architects to grasp the potential of computer designs. His provocatively adventurous buildings were among those that liberated modernist architecture from its conventions, expanding the boundaries of what buildings could be and how they could make people feel. His death marks the end of an era for one of the most celebrated and influential architects of the past half-century.

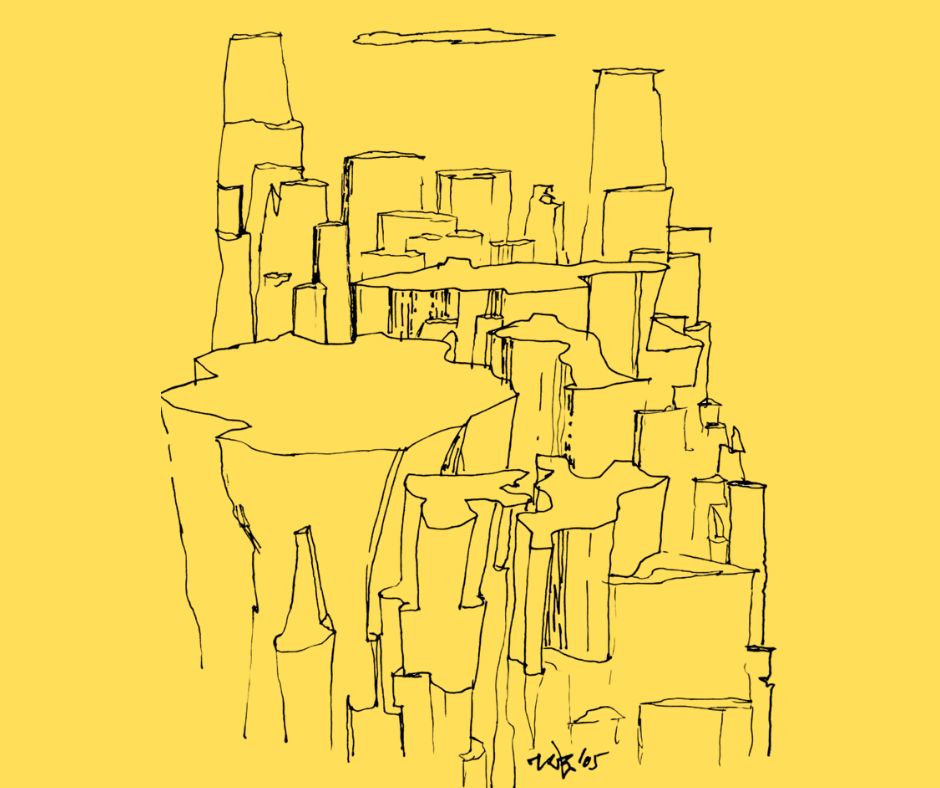

Born Frank Owen Goldberg on February 28, 1929, in Toronto to Polish immigrant parents, Gehry’s creative journey began in his grandmother’s company. He was encouraged by his grandmother, Leah Caplan, with whom he built little cities out of scraps of wood from her husband’s hardware store.

After studying architecture at the University of Southern California and urban planning at Harvard, Gehry established his Los Angeles practice in 1962. His breakthrough came in 1978 when he renovated his own Santa Monica home using unconventional materials, including chain-link fencing, corrugated metal, and plywood—a project that announced his departure from traditional architectural conventions.

Gehry was in his late 60s when he received the commission for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, perhaps the most critically acclaimed and renowned building of his career. When it opened in 1997, the titanium-clad museum became an instant sensation, transforming the struggling industrial city into a major cultural destination and generating what became known as the “Bilbao Effect”—the transformative economic and cultural impact a single iconic building can have on a community.

“I was rebelling against everything,” Gehry said in an interview with The Times in 2012, explaining his antipathy toward the dominant architectural movements of the time.

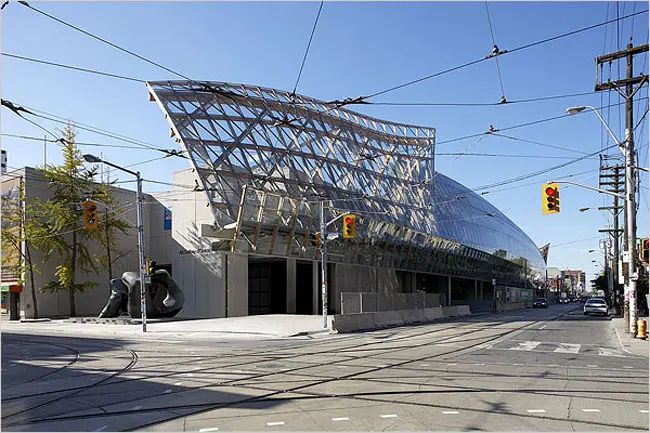

Gehry’s other most celebrated works include Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles (2003), Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris (2014), Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto (2008), Biomuseo, Panama City, Panama (2014), Neuer Zollhof, Düsseldorf, Gehry House, Santa Monica, Loyola Law School, California, Dancing House, Prague (1996), Olympic Fish Pavilion, Barcelona, Spain, Jay Pritzker Pavilion, Chicago, Cinémathèque Française, Paris, and Marta Herford, Herford, Germany, to list a few.

He received the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1989, the National Medal of Arts, and the Royal Institute of British Architects gold medal. His native Canada honoured him as a Companion of the Order of Canada. The 2010 World Architecture Survey ranked his works among contemporary architecture’s most significant, with Vanity Fair declaring him “the most important architect of our age.” In 2016, he was honoured with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by former President Barack Obama.

His influence extended far beyond individual buildings. Gehry fundamentally changed how cities think about architecture’s power to transform communities, inspire civic pride, and attract global attention. He is survived by his wife, Berta, and three children. Frank Gehry leaves behind a portfolio of buildings that will continue to inspire architects and delight visitors for generations to come.

“You go into architecture to make the world a better place. A better place to live, to work, whatever. You don’t go into it as an ego trip.” Gehry said in 2012. He added, “That comes later, with the press and all that stuff. In the beginning, it’s pretty innocent.”