We live in a world of manifest phenomena. Yet, ever since the beginning of time, man has intuitively sensed the existence of another world: a non-manifest world whose presence underlies – and makes endurable – the one we experience every day.

The principal vehicles through which we explore and communicate our notions of this non-manifest world are religion, philosophy and the arts. Like these, architecture too is myth-based, expressing the presence of a reality more profound than the manifest world in which it exists.

As the centuries progress, the myths change. New ones come into being, are absorbed, ingested, internalised – and nally transformed into a new architecture. Each time this metamorphosis occurs, a new era – a vistāra – opens up to our sensibilities. To classical Indian musicians, singers and dancers, the expansion outward into space is also, simultaneously, a journey inward into our own selves. Experiencing these expansions, these vistāras, heightens our consciousness.

The history of Indian architecture has been an extraordinary progression of such vistāras.

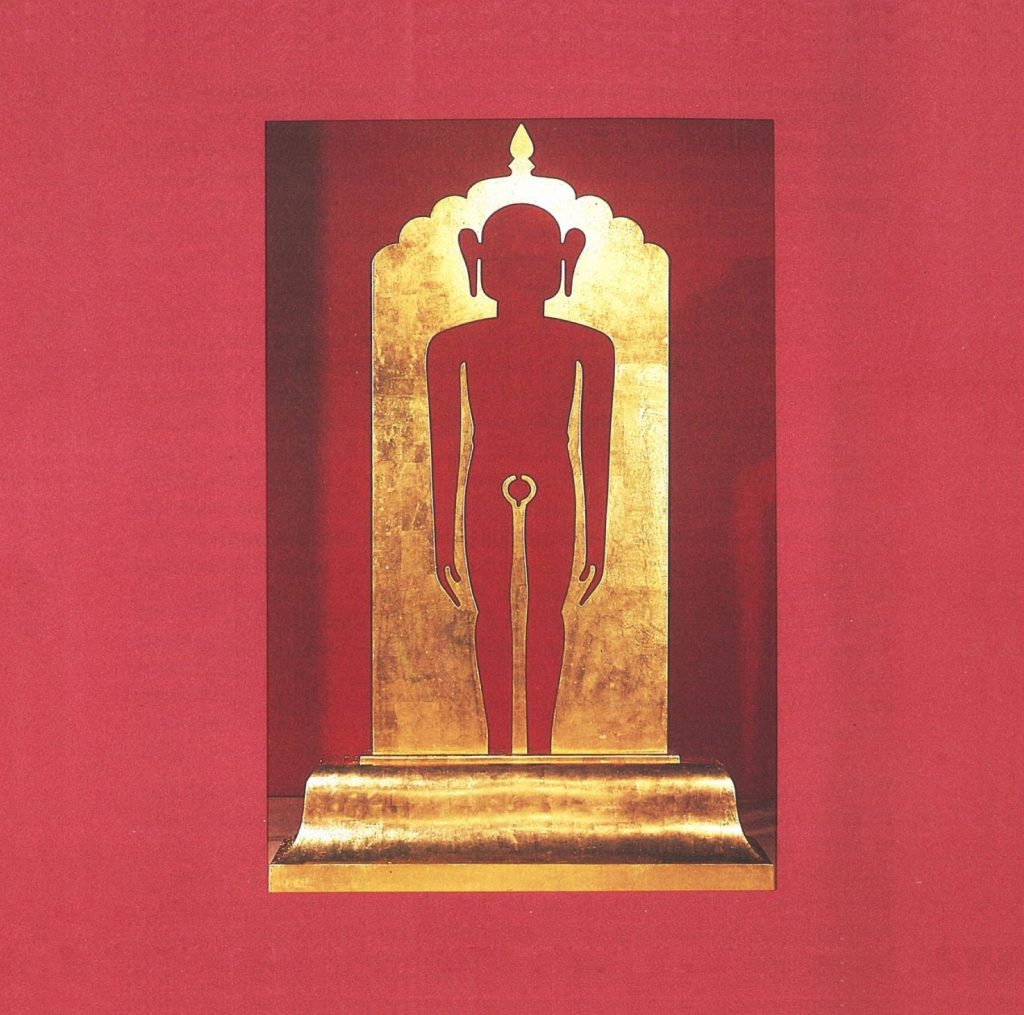

Central to all these vistāras – and to our exhibition – stands Purusha, a large-scale replica of an ancient Jain icon representing man in his two principal aspects: human and cosmic. For this is how, thousands of years ago, man perceived himself and his context.

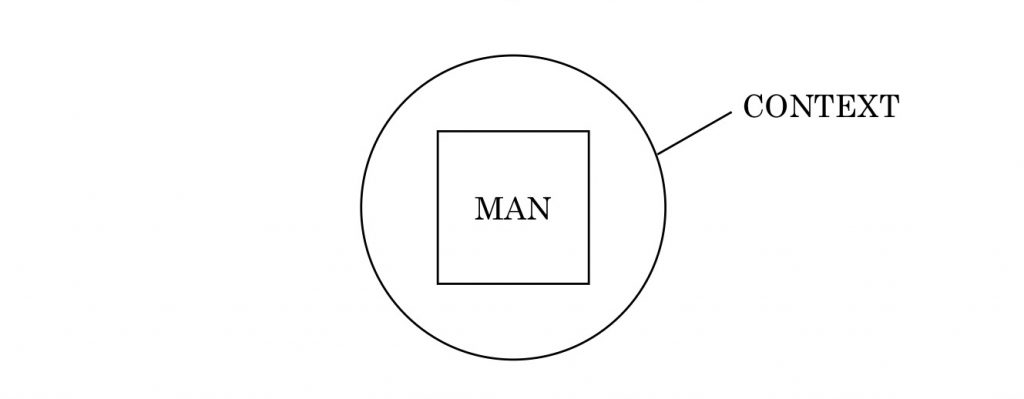

Down the centuries (and perhaps across the globe as well) man does not change. But the context in which he perceives himself to exist varies considerably. The qure of Purusha here is thus being used to represent not only man human and cosmic, but the more generalised condition of man and his context (i.e. the encompassing circle).

Down the centuries (and perhaps across the globe as well) man does not change. But the context in which he perceives himself to exist varies considerably. The qure of Purusha here is thus being used to represent not only man human and cosmic, but the more generalised condition of man and his context (i.e. the encompassing circle).

In Vedic times, that circle is the cosmos itself – and man’s central concern is to de ne himself and his actions in relation to it. Thus even the buildings he constructs are models of the cosmos – no less. They are generated by magic diagrams called Vastu-Purusha Mandalas. These represent energy- elds, the centre of which is simultaneously both shunya (nothing) and bindu (the source of all energy) – a truly mind-blowing concept, astonishingly similar to the black holes of contemporary physics.

In Vedic times, that circle is the cosmos itself – and man’s central concern is to de ne himself and his actions in relation to it. Thus even the buildings he constructs are models of the cosmos – no less. They are generated by magic diagrams called Vastu-Purusha Mandalas. These represent energy- elds, the centre of which is simultaneously both shunya (nothing) and bindu (the source of all energy) – a truly mind-blowing concept, astonishingly similar to the black holes of contemporary physics.

With the coming of Islam, the circle changes: man’s context is seen to be in part a judgemental relationship with an all-powerful Divinity, and in part a social contract (as in the Christian precept: Love thy neighbour). The central mythic images underlying architecture change too – as one can see by comparing the metaphysical landscape of a Jain cosmograph with the sensuous delights of the char-bagh of Islam.

Later, with the arrival of Europeans, the context changes yet again. The circle becomes the Age of Reason – and its concomitants: Rationality, Science, Technology. Perhaps today, as we reach the end of the 20th century, the circle is changing once more. In the West, the myths of technology and progress are being replaced by a concern for environment, for ecology. Man’s thoughts, actions – and architecture – will change to re ect this, and a new vistāra will open up.

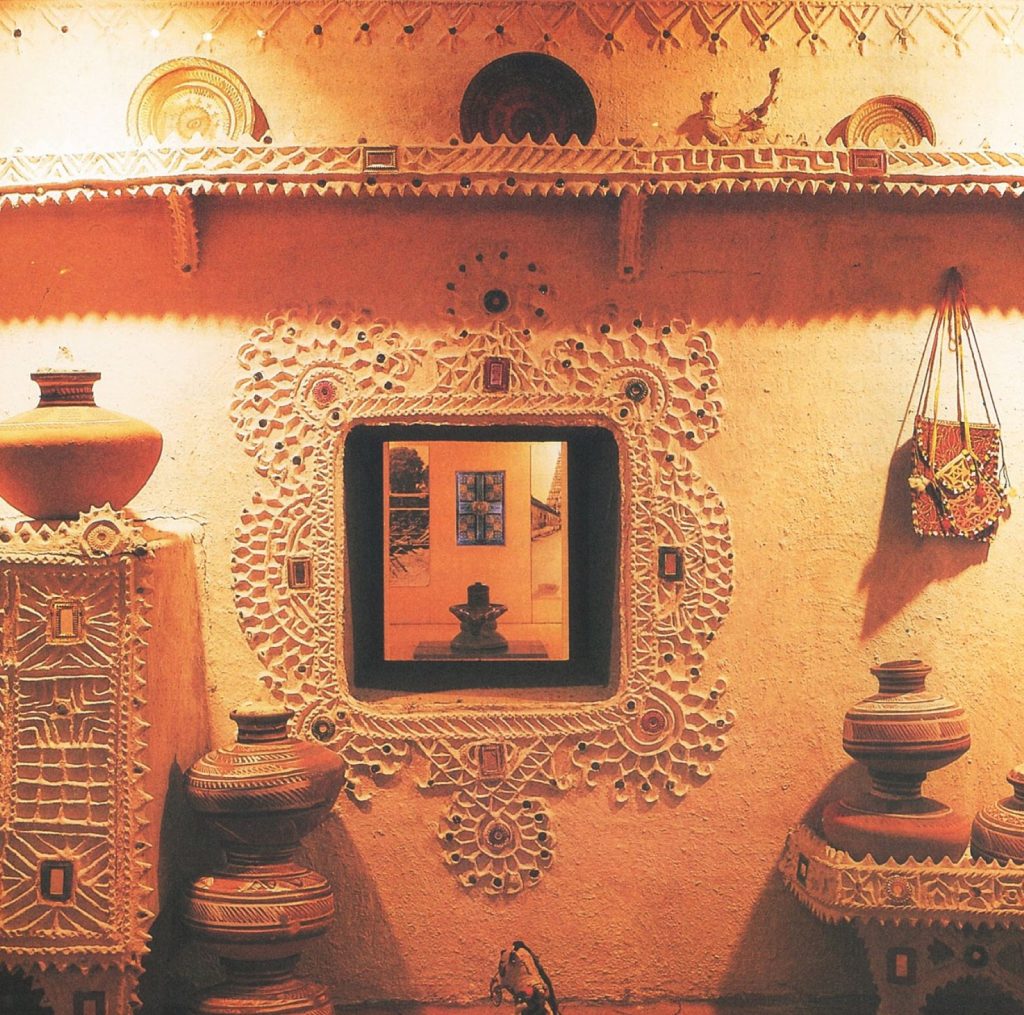

In each successive metamorphosis, the human aspect of Purusha seems to stay constant. This is vividly exempli ed in the habitat which he builds for himself, using a vocabulary and a syntax that seems immutable. Thus we have the mud houses of Banni, simultaneously both only a few years old – and a few thousand as well. In these building processes, as natural and organic as birds building nests, the mythic values seem implicit in human nature itself – hence the generic title Manusha (i.e., of man) for this section of the exhibition. Here we nd examples ranging from the fortress town of Jaisalmer to the squatter colonies of Bombay.

But even in these squatter colonies, generated by the brutal economic forces rampant on our urban scene today, we nd all of a sudden a gesture, an image – the rangoli before a front door, the butti on a sari, the bindu on a forehead – that makes us realise these patterns have been generated by an age-old deep-structure of more explicit myths: the yantra, the mandala, the char-bagh.

With time, of course the myths change – sometimes through outside interventions, sometimes re-surfacing from our own past. The resulting con ict, tension, churning, that then takes place, we have called Manthana. In this churning, it is crucial that we distinguish between a process as basic and structural as a Transformation, and one as super cial as a mere Transfer. Transformation involves as absorption, an internalisation – and ultimately a re-invention – of the myth. Hence Diwan-i-khas in Fatehpur-Sikri, where Akbar is sitting in the centre of a mandala on a column which clearly represents the mythic axis of the universe. Akbar has not only created an extraordinary piece of architecture, but also an incredibly powerful political statement. He is using the old myths to tell us that a new order has arrived. Compare this transformation with what Lutyens did three centuries later in New Delhi: a mere transfer of some imagery from Buddhist architecture without any care whatsoever for the profound mythic values from which it sprang.

What are the myths of today? It is dif cult for us to see the forces that move us in our own lives. But when we come across a glass skyscraper in some new city of the Arabian Gulf, it is possible to perceive how insidious (and lethal) are the myths of downtown America. Look around India today. How much of our lives does not also involve this kind of super cial transfer? Tragic, indeed, for this to happen in a land that once conceived of architecture as a model of the cosmos. Tragic, indeed, that students today are not told about these concepts in architectural schools – not even in the history classes. And certainly not in the design studios – where they rightfully belong.

What are the myths of today? It is dif cult for us to see the forces that move us in our own lives. But when we come across a glass skyscraper in some new city of the Arabian Gulf, it is possible to perceive how insidious (and lethal) are the myths of downtown America. Look around India today. How much of our lives does not also involve this kind of super cial transfer? Tragic, indeed, for this to happen in a land that once conceived of architecture as a model of the cosmos. Tragic, indeed, that students today are not told about these concepts in architectural schools – not even in the history classes. And certainly not in the design studios – where they rightfully belong.

For architecture is not created in a vacuum. It is the compulsive expression of beliefs (implicit or explicit) central to our lives. When we look at the architectural heritage of India, we nd an incredibly rich reservoir of mythic images and beliefs – all co-existing in an easy and natural pluralism. Each is like a transparent overlay – starting with the models of the cosmos, right down to this century. And it is their continuing presence in our lives that creates the pluralistic society of India today.

This then has been the purpose of this exhibition: to make explicit these overlays and their relationships, one to the other. For the architectural masterpieces from our past are not just wondrous pebbles which we as savages have found on our sea-shore. On the contrary. Each one is a crucial and decisive step in the successive vistāras that constitute our history.

Charles Correa

[newsletter-pack newsletter=”14013″ style=”style-1″ si_style=”t1-s4″ show_title=”0″][/newsletter-pack]