Aakrati Akar in conversation with Jinu Kurien, Principal Architect at DesignWorks, on the design of Euro School, Jodhpur.

AA: According to you, are there any changes required in the Educational Governing Body school building guidelines?

JK: Governing bodies define spatial guidelines in broad terms, and are usually not prescriptive in nature. So, that by itself may not be limiting. However, besides the governing body guidelines for projects in India, we are also expected to follow the National Building Code and local building regulations. There are conflicting positions and also ambiguity between these guidelines.

It will be good to have them clarified and reconciled. Guidelines should also aim to be more inclusive and sensitive to gender concerns and neurodiversity

AA: In the project brief or on the site, what challenges led to significant design considerations?

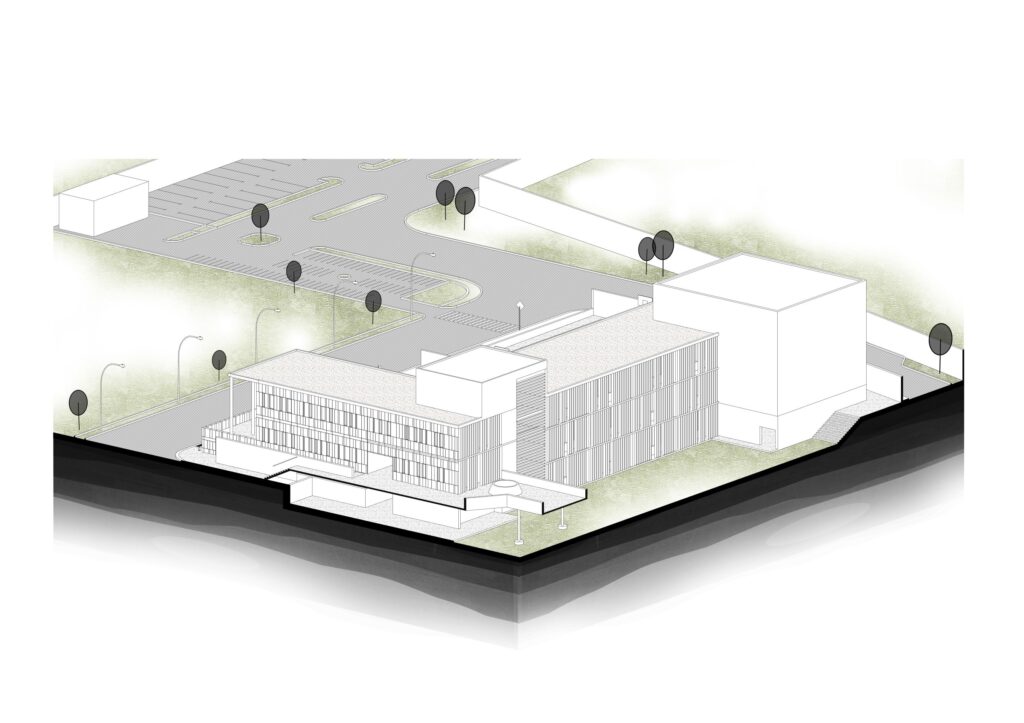

JK: This high school campus is located in Uchiyarda, just outside the city limits of Jodhpur. The school has a small kindergarten-primary campus located in the city which we designed in 2009, and this is a larger extension of that. The site is about 3.5 acres and can be accessed through a small connector from the Jaipur Highway. The connector then leads to the larger expanse of the site which is largely rectangular, even terrain and devoid of any vegetation.

The project brief had several dimensions but there were four broad intentions that we defined. First, to design a school that would bring delight to students and teachers. Second, to create a good balance of academic, sports and co-curricular amenities. Third, to design a campus that could develop in phases and fourth, to ensure that the school is responsive to the local climate.

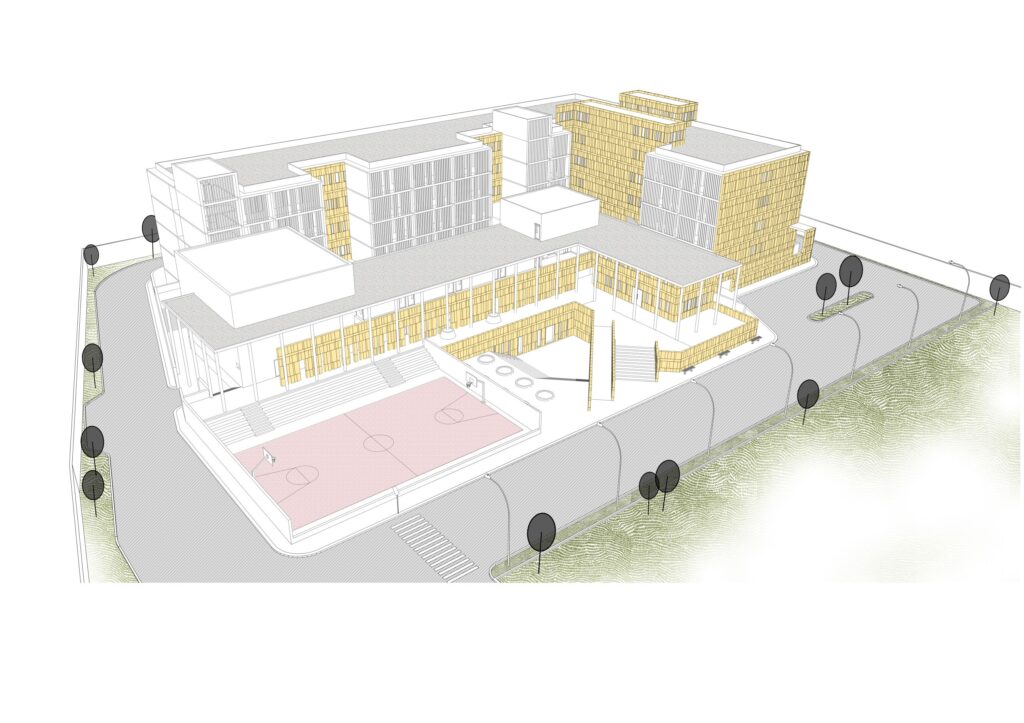

Our first move was to locate the playground on the site. An ideal playground occupies 2 acres, which in this case would reduce the buildability of the site. So, based on the limits of size and the ideal north-south orientation for a playground, we aligned it to the northeast corner of the site. This position also helped us define clear means of access and also helped us define the buildable portion of the site. It also meant that the arrival experience at the school passed through all the sports facilities. This was a gesture that we wanted to make.

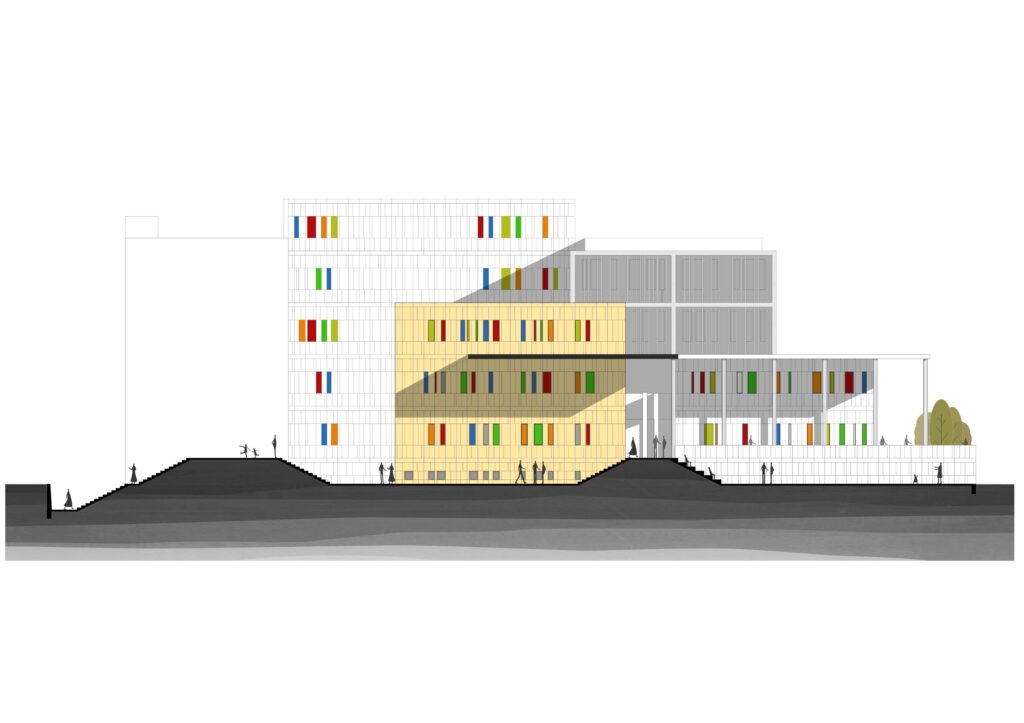

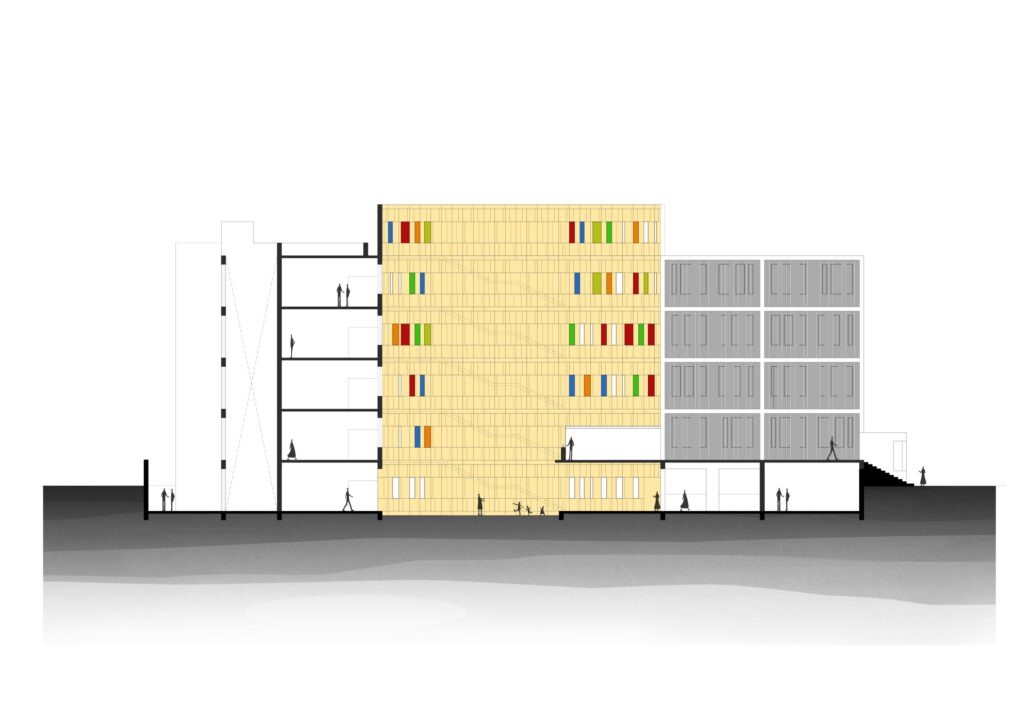

Having established this, the work extended to various forms of the organisation before we settled for two nested L-shape blocks. The block on the front is the first phase of the school and the two arms of the rear block become phases two and three. Since we intended to achieve a low-height but high-density organisation, we decided to stratify the building in its cross-section and created a lower ground floor with sunken courts and light wells. This helped us control the scale of the building and also enabled us to create social spaces like an amphitheatre and connectors by playing the level differences to our advantage.

The school unfolds in layers. A combination of ramps, steps, connectors and light wells create rich experiences of movement and play through the spaces. A set of walls and screens in sandstone, and thin fenestrations enable the layering of the facades.

The courts and light wells create an interplay of light and shadow. They all come together to create delightful and climate responsive spaces.

AA: From learners to teachers to support staff, the school building is home to a diverse set of users. How does the planning address the needs of the diverse set of user groups?

JK: The design brief and expectations for private schools are often set by individuals or organisations

that are outside the conventional definition of end users. The brief is often drafted by a charitable

trust and/or a developer and/or the school management. This brief is dominated by quantitative

parameters that include the following:

- School infrastructure requirements of the accredited board (CBSE/ICSE/state)

- Local building regulations and FSI computations

- Built-up area, phasing strategy, construction costs, long-term operating costs and

commercial sustainability of a school

These parameters are constants in the design brief of all schools and have an overarching impact on the planning and design of the school.

Qualitative parameters of the project brief include the following:

- Place: site, local climate, context and building practices

- People: learners, teachers, parents, support staff and school management

- Program: curricular, co-curricular, administrative and allied spaces, sports infrastructure.

The planning and design of Euroschool is a balancing act of all the above parameters and more.

Amongst the user groups, the position of the learners and the teachers took precedence over the others.

A good understanding of the modes of habitation and engagement of the learners and teachers is critical to the planning and design of the classrooms and the other enclosed spaces.

Every space is designed as a combination of the shell and a set of objects that enable the engagements envisaged within it. The design of these spaces and objects is defined by the number of learners and teachers in each space and the ergonomics, functional and operational parameters, and building services. Special attention was given to the quality of light (designed for digital and analogue learning) and thermal comfort in these spaces through the design of windows and louvred building skin.

The spaces outside these enclosures, what we call the ‘in-between’ spaces and the open spaces were as critical. They were designed to enable rich spatial and kinetic experiences, planned and unplanned encounters, play and delight.

Parents are also an important user group in any academic environment. They are crucial to the decision-making process for admissions. One parameter that drives this decision in favour of the school is its infrastructure. The school was planned such that the arrival experience showcased all the sports amenities and the amphitheatre to the parents before they got to the reception and the academic spaces.

The parent journey or experience was designed to instil comfort and confidence, and images of their child’s future in the school.

AA: Does the phased construction have any impact on the design of upcoming blocks?

JK: Developing schools in phases makes immense financial sense for the school developers since it enables the balancing of investment, revenue and operating costs. Conversely, developing the entire school infrastructure in a single phase can be taxing. Since a phased development was clearly defined in the project brief, we ensured that the master planning accounted for it. We adopted a horizontal phasing strategy such that each phase was an independent building that could be bridged by connecting spaces.

The phasing accommodated the sports infrastructure and the L-shaped block in the foreground in Phase 1. This meant that the public interface of the school would always look complete. The second and third phases were planned to the rear side of the block in the foreground such that construction activities in the future could be concealed and also executed with safety parameters. The organisation of the school with two nested L-shaped blocks is an outcome of the phasing strategy in the project brief.

AA: Over time, curriculum and pedagogy evolve, and how are these factors taken into account in school design and planning?

JK: With respect to school planning and design, our provisioning for future disruptions in technology,

curriculum and pedagogy included the following:

- Creating a structural grid with large spans that could allow easy expansion, contraction and

replanning of spaces. - Creating a series of ‘in-between’ spaces that enable multiple modes of community activities,

planned and unplanned encounters. - Provisioning for service shafts and routing networks for additions and modifications in

building service

Read more about Euro School, Jodhpur, here.