The early decades of the 19th century saw the beginning of the art of photography. Taking forward this revolutionary invention, as the world neared the 20th century, cameras, photo printing, and photography continued to evolve- by the mid-1800s, cameras had replaced the brush, as photo studios and travelling photographers emerged.

The early decades of the camera found its way to Asia- a land known for its diverse landscapes and architecture.

From hand-coloured photographs of Imperial Calcutta, India by Frederick Fiebig (in the mid-19th century) to black and white photographs of Kandahar, Afghanistan by Benjamin Simpson to coloured street photography by Raghubir Singh (who would often cite Bengal as the place where modernism first amalgamated with the vernacular), since the region’s introduction to camera, the art of photography in South Asia stayed in tandem with the development of the West.

Ruins of the old Kandahar Citadel, by Benjamin Simpson, 1881 (Source: Sir Benjamin Simpson (1831-1923), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Along with this rapid development in photo-printing technology, a parallel occurrence was the growing sense of nationalism in an entire region of the Asian Continent- the coming century was to observe the Independence of all the colonised South Asian countries.

And together with the decades that were to follow their independence, these instances were to become the muse of innumerable photographers worldwide. Along with the independence struggle, the camera became a medium to document the journey of the newly-independent nations. From mega-scale plans of new cities to structures of power to the challenges of a region that was, until recently, accustomed to being governed by colonisers, photography captured the trajectory of different South Asian countries establishing their new identity. As new nations emerged, photography would present the contrasting views of colonial and nationalist.

For a country like India, which had a literacy rate of 12% post-Independence in 1947, visual mediums also became the most widely used approach for disseminating information.

As the country’s architecture saw trifurcation into three different ideologies in search of this identity, its documentation brought a new perspective towards architectural photography; where colonial India focussed on capturing traditional architecture and its elements, the grandeur of palaces and forts, the mid-20th century observed a major change for two countries that were once part of one empire, in the form of one of the World’s largest refugee crisis and the rapid shift in infrastructure it called for.

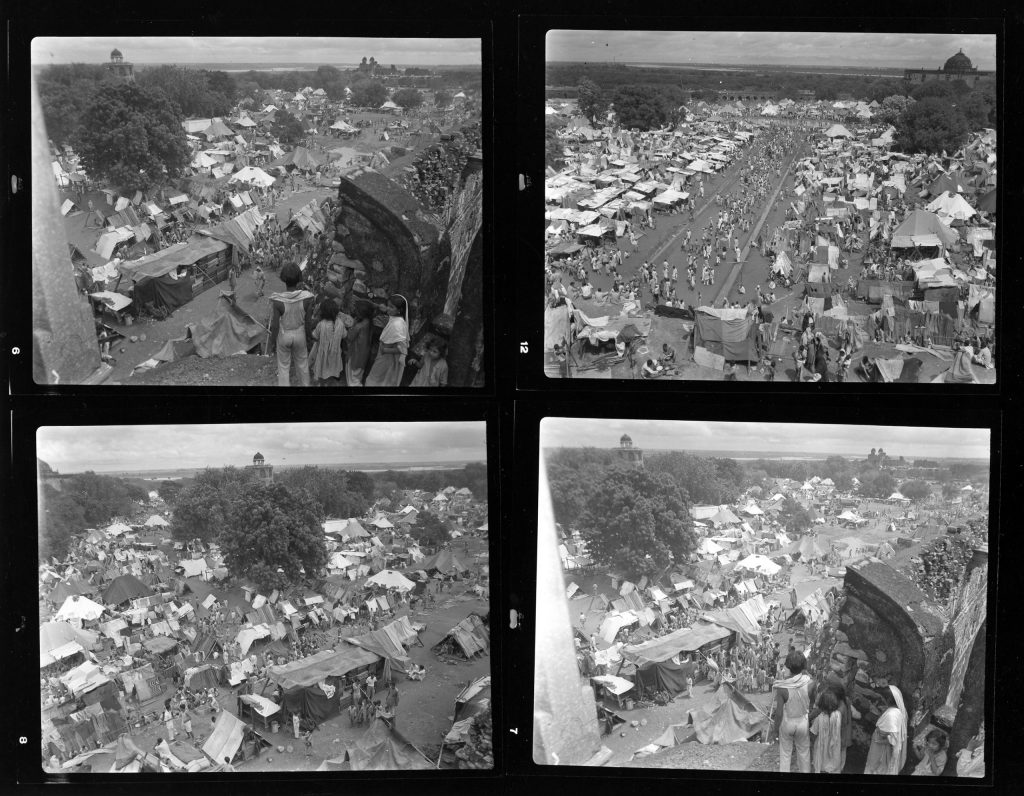

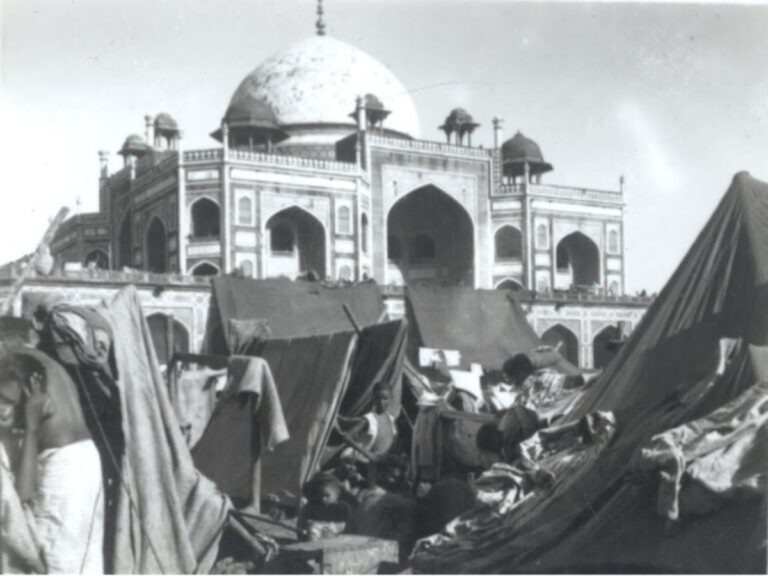

Inundated with temporary shelters, the tombs that were once captured because of their architecture were now being documented for the usage of space. Along with the compulsive need to make a mark, the urgency to accommodate the migrated population led to a rapid infrastructure boom in India and Pakistan. Whether the continuity of the British introduced Indo-Sarcenic Architecture, revisiting the region’s Pre-colonial Architecture or shifting towards the then-global trend of Modernism- photographers engaging with the built managed to capture this landmark moment and the evolution that followed.

While the British departed, several photographers from the West came to document the refugee crisis. Amongst these was American Photographer Margaret Bourke-White, a pioneer in her own way. In her collection of images capturing the refugee crisis for LIFE magazine, one can see the transformation of the places of religion, forts and tombs as they became temporary homes to millions of displaced.

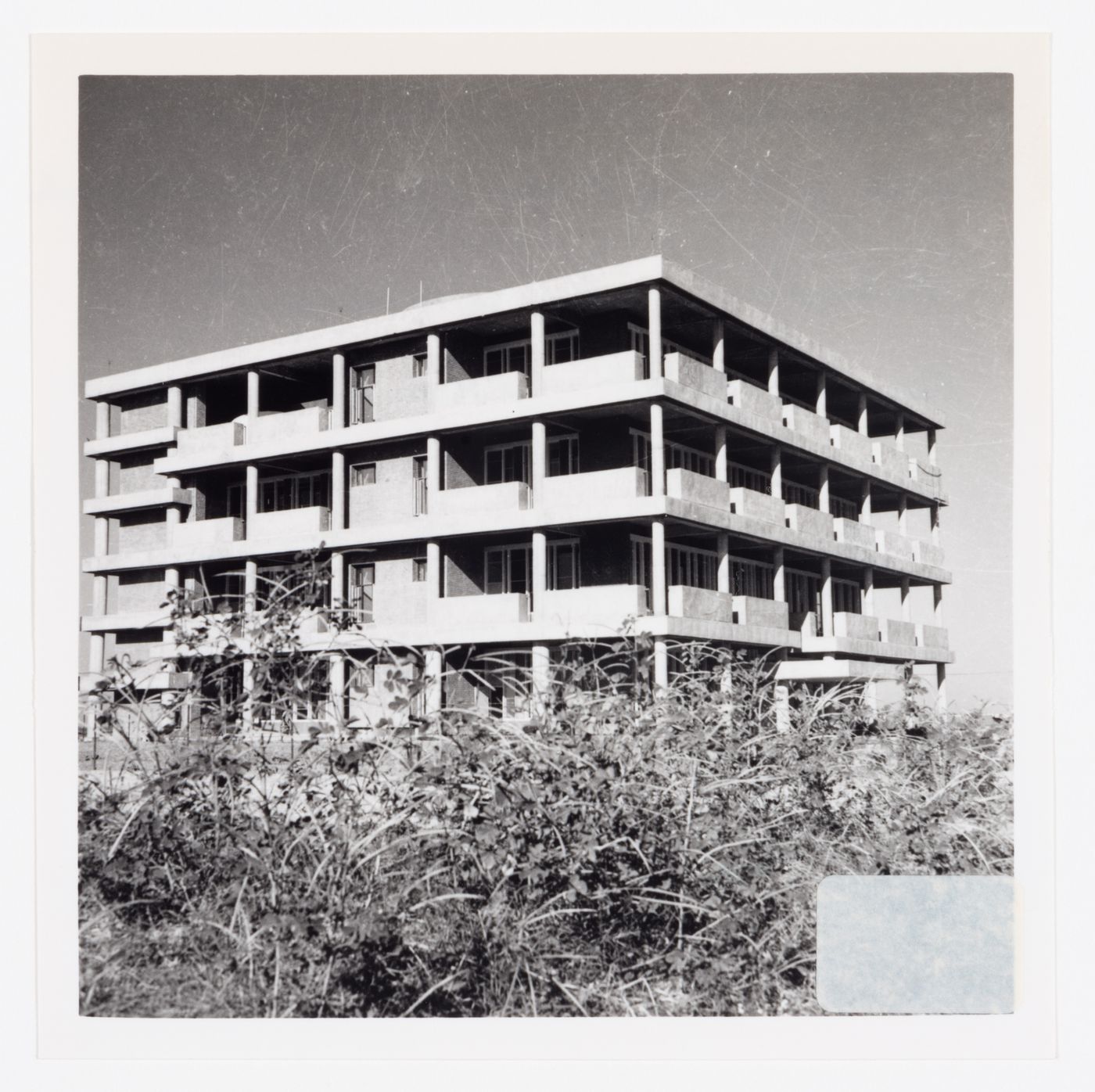

To accommodate this large population, both nations struggled with their existing infrastructure- new refugee colonies, railway network development, and cities came up; where India had Chandigarh, Pakistan planned its new capital- Islamabad.

Perhaps the crowning jewel of the nation’s Infrastructure roadmap, the Indian state of Punjab’s new capital Chandigarh was India’s method of establishing itself in the global phenomenon of modernism. Its process was closely documented by several photography enthusiasts, including one of the project’s architects (cum photographer)- Jeet Malhotra.

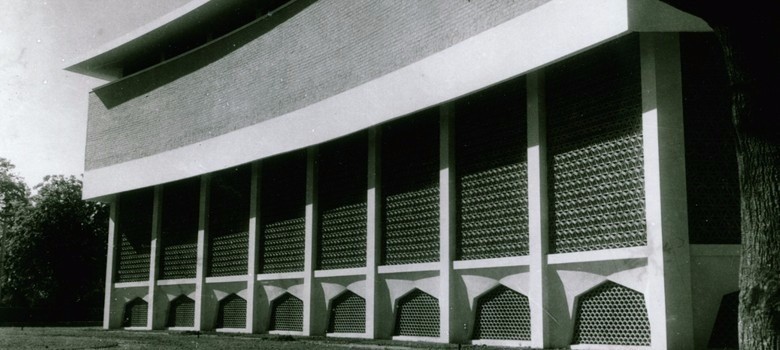

While India had Chandigarh, Pakistan built Islamabad- the country’s new capital. Documenting the city’s architecture- an amalgam of modernity and Islamic architecture were the commissioned photographers of the government departments.

Gradually, modernism became a part of much of South Asia’s architecture. From Ram Rahman’s early documentation of his architect father Habib Rahman’s buildings to one of India’s most revered and earliest formally trained architectural photographers- Madan Mahatta’s documentation of Delhi- India’s photographers captured the process of modernism becoming the sought-after vocabulary in the country.

While Delhi was exploring modernism, the island country Sri Lanka’s capital- Colombo, was witnessing an adapted style of it- tropical modernism. This could be witnessed in the works of architects Geoffrey Bawa and Minette de Silva. The latter’s first commissioned work in Colombo- Pieris House, photographed by photographer Lionel Wendt, incorporated design details that were eventually explored by Architect Geoffrey Bawa. As Bawa’s influence continued to increase in architecture, his works became a significant part of Sri Lanka’s architecture, being documented by several photographers such as Dominic Sansoni. Dominic went on to actively document the vernacular architecture of South India, along with the sacred spaces in Sri Lanka.

A unique perspective towards sacred spaces was put forth by Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam- a social activist and photographer. His photo series on the Bait Ur Rouf mosque in Dhaka was exhibited within the mosque itself.

Alam’s more recent capture of the Balukhali refugee camp immediately takes one back to the shelter tents of 1947 squeezed to inhabit a large number of displaced.

These photographic records point out not just the trajectory in architecture- but the similarities in the treatment of space by humans. Whether it was 1947’s Humayun’s Tomb in India or 2022’s Kot Diji in Pakistan- it takes one disaster to transform the usage of space and shift the lens’ focus from the structure.

Architectural Photography has been used for a variety of reasons- ranging from the depiction of historical moments to documenting heritage to showcasing modern buildings or promoting new designs.

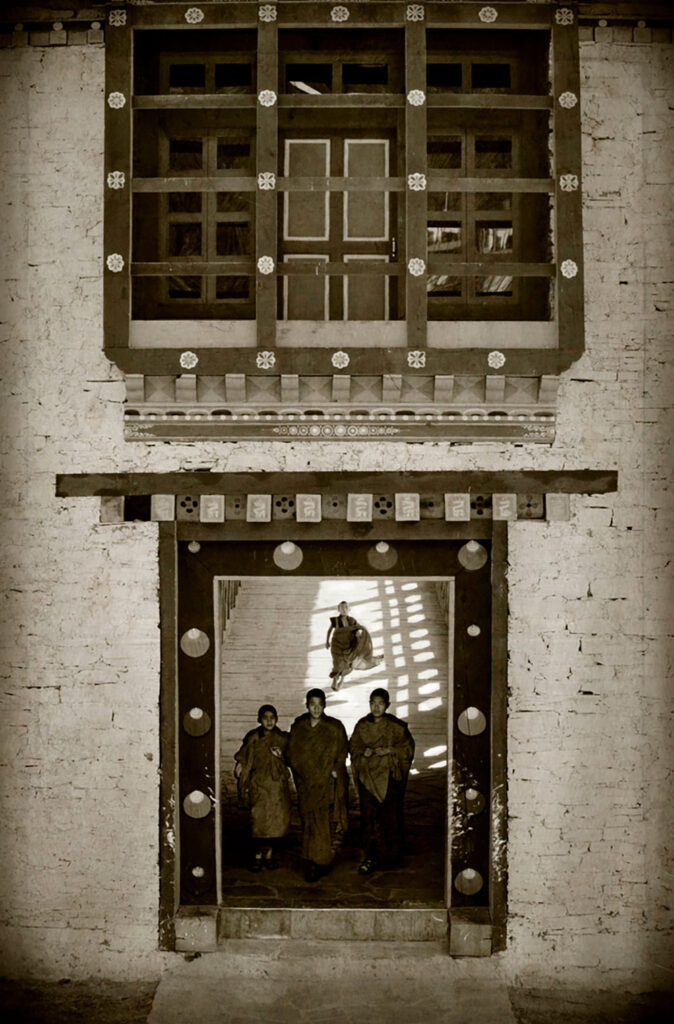

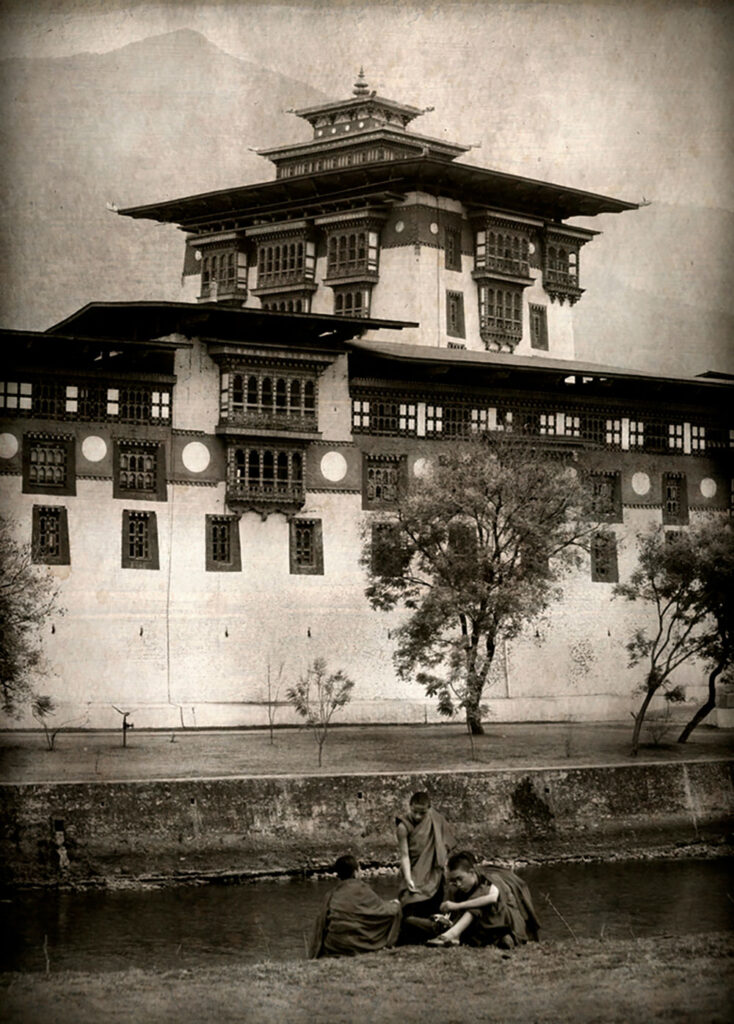

Since the early years of the invention of the camera, photography has played a role in documenting, presenting and celebrating the built environment. Whether through Nipun Prabhakar’s documentation of the Doors of Kathmandu or the birdhouses of Kutch, Raghu Rai’s documentation of Delhi or Richard Murai’s capture of the pagodas of Bhutan- the photographer manages to provide the audience with the experience of a space translated through their lens.

In South Asia, architectural photography has become more significant as the region has undergone a tremendous transformation in architecture and urban development. From the post-colonial era to the present day, when it is embracing new technologies and designs, architectural photographers have been constantly archiving this evolution.

This is where the significance of photography lies.

Through its ability to convey the essence and beauty of architecture to a diverse audience, a photograph can capture the mood, scale, and detail of the buildings and narrate a story written by the architect or the photographer!

Aakrati Akar, ArchitectureLive!

Featured Image: Bait Ur Rouf mosque in Dhaka (Source: Shahidul Alam via scroll.in/magazine)