With rapid urbanization and population growth, there is a growing demand for land, leading to increased pressure on existing urban areas and surrounding rural land. In this context, the practice of bulldozer urbanism, with its potential for rapid evacuation of extensive tracts of land, has gained prominence as a means of meeting this demand.

Mehar Deep Kaur

Urban development has been a contentious issue for decades, with different approaches generating divergent opinions and experiences. One such approach that has been in use for over half a century is bulldozer urbanism.

The photograph below provides a vivid illustration of bulldozer urbanism in practice, capturing the demolition of a house that has become a familiar sight in urban areas worldwide. The image depicts a recent incident that took place on May 18, 2022, in Khichdipur village, situated in the eastern region of New Delhi, India. The DDA initiated an anti-encroachment drive that required clearing the area, citing the village’s unauthorized occupancy of government property as the primary reason for action.

What is Bulldozer Urbanism?

Bulldozer urbanism is a term used to describe the culture of rapid clearance of large land parcels for urban redevelopment, resulting in the alteration of existing landscapes. This process can be carried out through various techniques; however, the utilization of heavy machinery is prevalent, with bulldozers being the equipment most frequently deployed.

Bulldozer urbanism has emerged as a critical issue in today’s dynamics of urban development. With rapid urbanization and population growth, there is a growing demand for land, leading to increased pressure on existing urban areas and surrounding rural land. In this context, the practice of bulldozer urbanism, with its potential for rapid evacuation of extensive tracts of land, has gained prominence as a means of meeting this demand.

However, it also raises questions about the costs and consequences of such development, particularly with regard to social equity and environmental sustainability.

While proponents argue that it can revitalize urban areas and spur economic growth, critics point to its detrimental effects on communities and cultural heritage. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of bulldozer urbanism, encompassing its historical and contemporary background and the diverse ramifications it carries.

The Emergence of Bulldozer Urbanism

The history of bulldozer urbanism can be traced back to the 1950s when it was first used in London as part of an effort to clear slums and make way for modernist architecture. This method was later adopted by other European cities such as Paris, Hamburg, Amsterdam and Frankfurt, where it was used alongside other forms of urban development such as high-rise housing projects and public housing estates. However, it was the reconstruction of Warsaw after World War II that marked the first use of bulldozers in urban development.

Eventually, bulldozer urbanism became a popular approach to urban development in the mid-20th century, particularly in North America and Europe, as city planners sought to revitalize urban areas by removing older, dilapidated buildings and replacing them with modern infrastructure.

However, the practice was often implemented without much consultation with local communities and involved demolishing large swaths of urban areas deemed “blighted” or “slum-ridden”. This approach led to the displacement of residents and the destruction of cultural heritage, which resulted in the term “bulldozer urbanism” being coined in the 1960s to describe this widespread practice.

Although bulldozer urbanism was initially celebrated as a necessary step towards urban renewal, it soon became a controversial and divisive approach to urban planning, as the displaced communities were often neglected and deprived of adequate housing or support services.

One of the earliest examples of bulldozer urbanism was the St. Louis Pruitt-Igoe housing project, which was built in 1954 as a solution to the city’s housing shortage but quickly became known for its poor living conditions and high crime rates.

The project was eventually demolished on March 16 1972, marking a turning point in public opinion on urban renewal through demolition. While this obliteration was seen by some as a necessary step in revitalizing the area and removing blight on the city, others criticized the decision as an example of the negative effects of bulldozer urbanism, arguing that the demolition erased a significant piece of the city’s history and displaced thousands of residents who had called the complex home. Despite the controversy surrounding its demolition, there were both positive and negative effects of the Pruitt-Igoe housing project’s removal.

On the one hand, the removal of the project helped to reduce crime and improve the overall safety of the area. On the other hand, the demolition also left behind a vacant lot and displaced thousands of residents, many of whom were forced to move to other low-income areas with similar problems.

Another prime example of bulldozer urbanism is the construction of the Interstate Highway System in the United States during the 1950s and 60s. While this project aimed to improve transportation and connect different regions of the country, it resulted in the displacement of numerous Black communities.

The highway system was built through many urban areas, destroying low-income neighbourhoods and displacing thousands of residents, most of whom were African Americans. For instance, the construction of the I-94 expressway in Detroit displaced over 4,000 Black residents from the Black Bottom and Paradise Valley neighbourhoods. Similarly, the construction of I-5 in Seattle caused the displacement of the predominantly Black Central District community.

The displacement of these communities was rooted in racism and discriminatory policies, including redlining and restrictive policies, which limited Black people’s access to desirable housing options.

The highway system’s construction perpetuated these policies by effectively cutting off Black neighbourhoods from the rest of the city and leaving them isolated.

The Contemporary Era of Bulldozer Urbanism

In the present times of urban development, there exist various advanced techniques that can be employed for demolition. Therefore, it is important to recognize that the term “bulldozer” serves as a symbolic representation of the broader practice of demolishing structures, as other techniques like explosives and wrecking balls can also be utilized for these purposes.

One of the defining characteristics of the modern era of Bulldozer Urbanism is the continuance of the top-down decision-making process, with an absolute lack of consultation and participation from residents and communities. This has led to various negative social and cultural impacts, including displacement of long-time residents, loss of cultural heritage, increased social and economic inequality, erasure of community identity and the homogenization of urban landscapes.

The following sections provide a glimpse into recent case studies that exemplify the consequences of bulldozer urbanism.

The Razing of Khori Gaon, India

Khori Gaon, a 50-year-old settlement located on the outskirts of Delhi, India, has become a symbol of bulldozer urbanism. During the months of July and August 2021, amidst the Covid-19 pandemic and monsoon season, the settlement suffered a violent demolition, which impacted nearly one lakh residents who called the area their home.

The local authorities claimed that the residents of Khori Gaon had illegally occupied government land, which led to their order to demolish more than 10,000 houses in the area. They justified the eviction and destruction as necessary to clear encroachments on government land and to create a green zone. However, activists and residents argue that the government failed to provide adequate notice or compensation for the residents, leaving many without a means to support them after their homes were dismantled. The government also failed to offer alternative housing or job opportunities for the displaced residents. Despite the demolition of nearly 90% of the settlement, only 50% of the population could find accommodation in the nearby Satsang, leaving a considerable number of people without a place to live.

The situation in Khori Gaon highlights the complexities and injustices of Bulldozer Urbanism, in which vulnerable communities become soft targets and their livelihoods are destroyed in the name of development.

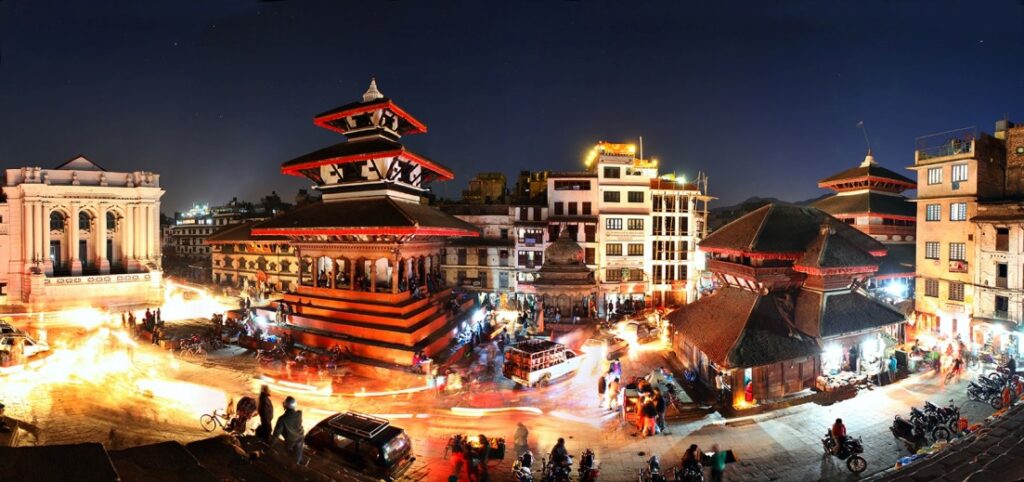

Bulldozed Heritage of Basantapur Durbar Square, Nepal

Basantapur Durbar Square, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Kathmandu, Nepal, is another prime example where government officials and developers forcefully demolished historical and cultural sites for economic development purposes.

The area was once the seat of the Nepalese monarchy and is home to numerous palaces, temples, and other historical structures dating back to the 12th century. The square was also an important centre of trade and commerce, and its significance has only grown over the centuries.

However, in the aftermath of the devastating 2015 earthquake that struck Nepal, the government initiated a reconstruction effort with the help of international donors to restore Basantapur Durbar Square. While the rebuilding of the square was necessary, the process has been heavily criticized for its lack of community involvement and consultation with heritage experts, which has resulted in the destruction of historical buildings and the replacement of traditional architecture with modern concrete structures that are not consistent with the square’s historical character.

The use of modern materials and techniques has also caused damage to the area’s cultural heritage and resulted in the loss of traditional building methods and materials, diminishing the local community’s historical identity, which further led to a decline in economic opportunities for them. Compounding these issues, the decision-making process did not involve the local community, leading to the inability to protect their cultural heritage, and no compensation or alternative housing was provided to those displaced by the demolition of their homes.

Though bulldozer urbanism is infamous for often being driven by the interests of real estate developers and urban renewal agencies to make way for new projects, there are also some cases in which the approach was employed for safety and legal reasons.

Regulating Urban Development through Bulldozer Urbanism- A Case of Noida

On 28th August 2022, the Supertech Twin Towers- Apex and Ceyane, situated in Noida, Uttar Pradesh, were demolished following a court order. The court claimed that the twin towers were built in defiance of the UP Apartments Act of 2010. Real estate regulations mandate that the space between two buildings must be 16 meters, and structures over 18 meters must be 16 meters apart; this spatial gap is essential for fire safety. However, the distance between the two towers was only 9 meters, thus violating fire safety norms. Approximately 3,700 kilograms of explosive material was utilized for the implosion of the structures.

This particular case study illustrates the paradox of bulldozer urbanism, which entails both regulation and destruction of spaces. However, it also emphasizes that the utilization of this approach is essential to safeguard public safety.

The Human Cost of Bulldozer Urbanism- A Case of Mehrauli

On February 10 2023, DDA initiated an anti-encroachment drive in Ladha Sarai village, a precinct that lies in the Mehrauli Archaeological Park, claiming that the land belongs to the government.

The authority demolished two shanties and an unoccupied five-storey building. As the drive continued, residents from eight housing complexes, each containing 15-25 flats, gathered on the road to prevent further demolition. They later approached a court seeking relief on account of being punished unfairly as the construction has taken place over the last five years in close proximity to the administration’s oversight.

Though this led to an almost immediate halt order on the demolition drive by LG VK Saxena, the individuals whose houses were already razed in the past week struggled to find both shelter and sustenance. Additionally, the locals reported a significant increase in rental rates for single rooms in the Mehrauli area following the demolition drive.

This case study presents how imperative it is for policymakers and authorities to consider the impact of their decisions on people’s lives before implementing such drastic measures. The bulldozer urbanism approach should not be used as a means of regulating and destroying spaces without taking into account the human cost.

The Politics of Bulldozer Urbanism

The above case studies raise broader questions about the complex relationship between bulldozer urbanism and politics – the role of government in managing urban development.

The debatable nature of bulldozer urbanism stems from various reasons, including its potential harm to vulnerable communities and the environment, as well as the possible infringement of legal and human rights. In particular, the approach of bulldozer urbanism is viewed as a direct violation of the fundamental constitutional rights of citizens.

This approach is often used to selectively punish members of marginalized groups while violating municipal and urban planning laws, which has a significant impact on the minority community. In recent protests against the Agnipath scheme in India, violence broke out across the country, causing damage to both public and private properties. However, the protestors, mostly belonging to the majority community, did not have to face any action.

The right to housing is recognized under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, while Article 300 A prohibits any person from being deprived of their property by the authority of law. As a result, the courts have a crucial role in using international law to counter nationalist-populist discourse and safeguard constitutional rights.

Any justification for demolition drives as a penal consequence of a criminal act goes against established criminal justice canons. Therefore, the law can be used to counter bulldozer urbanism by holding authorities accountable for violating the constitutional and human rights of vulnerable communities.

It is crucial for governments to prioritize the needs of local communities and consider the social, economic, and cultural implications of urban development projects.

The Multi-faceted Impacts of Bulldozer Urbanism

Despite its negative impacts, Bulldozer Urbanism has also led to technological innovations and advances in urban design and planning, making urban areas more efficient, sustainable, and livable, such as in the case of Songdo International Business District, South Korea. The area was built from scratch on a reclaimed land site in the early 2000s, using advanced urban planning tools, such as computer modelling and simulation, to optimize the layout and design of the city. While the development of Songdo involved bulldozing large swathes of land, it also demonstrates how such urban renewal projects can be leveraged to drive innovation and advance sustainable urban design and planning.

However, the benefits of these advancements have not always been evenly distributed, and the negative impacts of Bulldozer Urbanism continue to be felt in many urban areas around the world. In terms of the environmental impact of bulldozer urbanism, on one hand, it has helped reduce air pollution by reducing reliance on cars for transportation (through the creation of dense and walkable neighbourhoods), while on the other hand, it has led to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions due to increased construction activity. Bulldozer urbanism also has economic implications: it can help reduce unemployment by creating jobs for those who work in construction industries or related fields like architecture and engineering; however, it can also lead to higher costs of living because these new buildings tend not only be more expensive but also require more materials than older ones did.

The Way Forward

Bulldozer urbanism provides an important historical context for understanding contemporary debates about urban development, gentrification, and the displacement of marginalized communities. Though, bulldozer urbanism is frequently associated with the interests of real estate developers and urban renewal agencies, and the demolition of structures to make way for new projects, there are instances where its implementation is justified for reasons related to safety and legal compliance, as evidenced in the case studies of Noida and Mehrauli. However, while the approach has the potential to be an effective tool for urban renewal, it must be implemented with sensitivity and care for the needs of the affected communities.

As cities continue to grow and evolve, it is imperative that we learn from the mistakes of the past and embrace alternative models to Bulldozer Urbanism for future urban development.

One alternative approach is participatory urbanism, which involves the active involvement of citizens in the planning and decision-making process of urban development.

Giving citizens a voice in the planning and design process ensures that the development is inclusive and caters to the needs of all members of society, regardless of their socio-economic status or legal status.

Technology can be leveraged to streamline this process and increase citizen engagement, and participation in urban development projects.

Another approach that emphasizes environmental sustainability, social equity, and economic viability is sustainable urbanism. This approach prioritizes the use of renewable energy, the reduction of waste and pollution, and the promotion of public transportation and green spaces.

Moreover, the preservation and restoration of historic and cultural landmarks in the city can be prioritized, which promotes a sense of community and a connection to the city’s heritage.

These alternatives can help create cities that are not only livable but also sustainable and inclusive for all sections of society. As a matter of fact, it would be prudent to endeavour towards the adoption of a comprehensive synthesis of all these approaches as the optimal means of achieving holistic development.

However, these models face challenges in implementation, such as political resistance and lack of resources. It is crucial that we continue to advocate for these approaches and hold governments accountable for their impact on marginalized communities.

Ultimately, the success of any urban development project should be measured not just by its aesthetic appeal or personal benefits, but also by its impact on the lives of those who inhabit the cities.

Bibliography

- Bulldozer-Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape, by Francesca Russello Ammon

- https://thewire.in/rights/the-bulldozer-is-reshaping-our-cities-and-our-imaginations

- Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, by Kenneth T Jackson

- https://thewire.in/rights/the-bulldozer-is-reshaping-our-cities-and-our-imaginations

- https://www.archdaily.com/870685/ad-classics-pruitt-igoe-housing-project-minoru-yamasaki-st-louis-usa-modernism

- https://www.greyscape.com/modernism-was-framed-the-truth-about-pruitt-igoe/

- https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/pruittigoe?utm_medium=website&utm_source=archdaily.com

- https://www.latimes.com/homeless-housing/story/2021-11-11/the-racist-history-of-americas-interstate-highway-boom

- https://www.vox.com/2015/5/14/8605917/highways-interstate-cities-history

- https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/khori-gaon-demolition-rehabilitation-displaced-sc-haryana-7437948/

- https://www.outlookindia.com/national/how-bulldozers-dehumanise-the-urban-poor-news-195958

- https://www.thelongestwayhome.com/blog/nepal/kathmandu-durbar-square-is-an-atrocious-shameful-mess/

- Prospects and Problems Of Cultural Tourism: A Study Of Kathmandu Durbar Square Kathmandu, Nepal, Thesis of Kiran Dangol

- SHRESTHA, Suresh Suras. “HANUMANDHOKA DURBAR SQUARE: Post Earthquake Renovation and Rehabilitation of Cultural Heritage.”

- https://arunachaltimes.in/index.php/2022/06/20/courts-should-use-international-law-to-counter-bulldozer-politics/

- https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2009/05/the-suburban-bulldozer/17244/

- https://www.cnbctv18.com/india/noida-twin-towers-demolition-land-residential-project-supertech-explains-14636281.htm

- https://www.outlookindia.com/business/from-nine-years-to-nine-seconds-all-you-need-to-know-about-noida-twin-tower-demolition-news-219099

- https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/as-bulldozers-roll-in-mehrauli-residents-question-why-now/articleshow/97808818.cms?slideshow=97855106&slide=97855744#13

One Response

Shakespeare birth place building in a village of 20000 inhabitants attracts 6 million visitor annually. Building is preserved and yielding global economic returns. Bulldozer urbanism is spatial and justified on accounts that are seldom universal.