Contributed by Durganand Balsavar, Artes Roots Collaborative

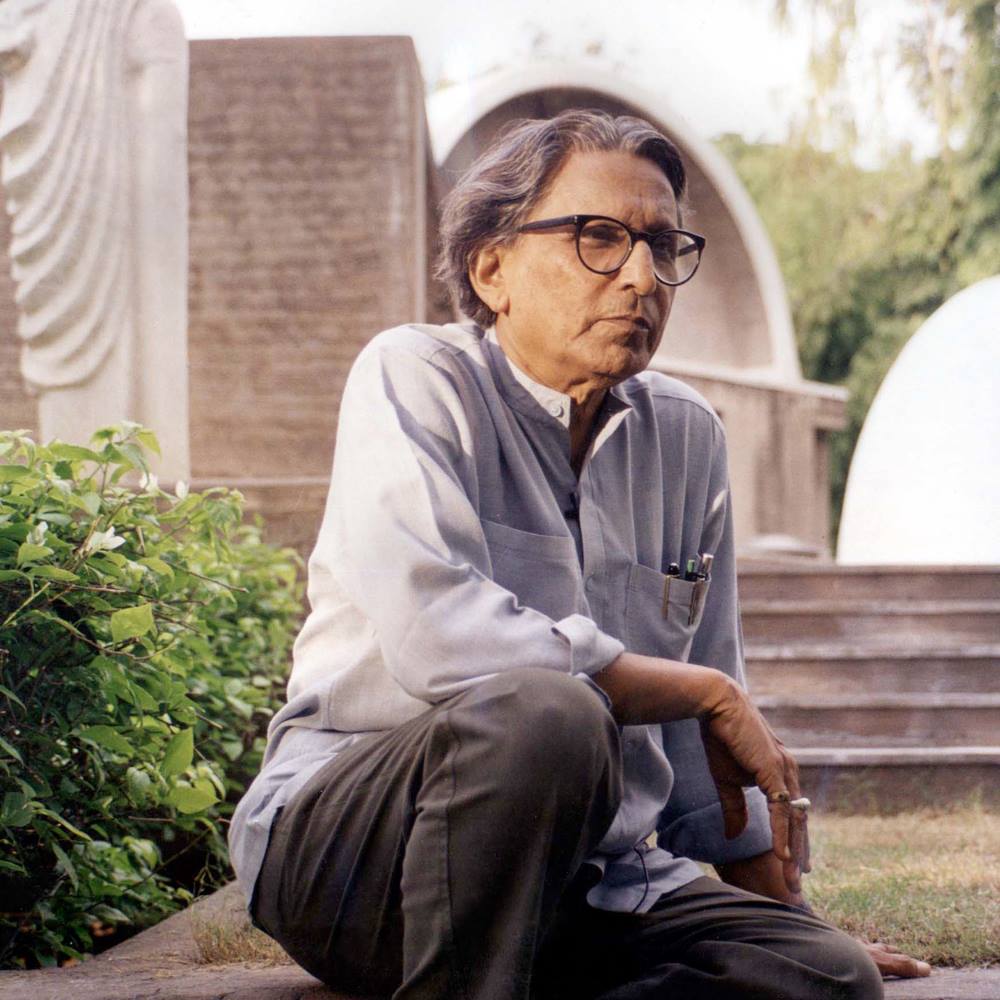

Internationally acclaimed architect, educationist, institution builder, B.V. Doshi turned 90 in August 2017, a huge milestone for one of the most prolific architects in the world today. Over the past seven decades, Doshi has received several prestigious international and national awards, among them the Padma Shri, and France’s highest civilian honour, Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and an honorary doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania.

We meet at Sangath, Doshi’s atelier in Ahmedabad, recently nominated as one of the best designs of the last century. Despite a harsh June sun, the atelier is cool inside, a testimony to the nonagenarian architect’s pragmatic understanding of Indian weather. Students from Venice have arrived to document the evocative vaulted studio. Doshi at 90 looks the same as he did 30 years ago—filled with pragmatism, relentless energy, alertness, and a passion for life and architecture. “My family enriches my life,” he tells me, pointing to a photograph of five generations celebrating Utran, the kite festival in Gujarat.

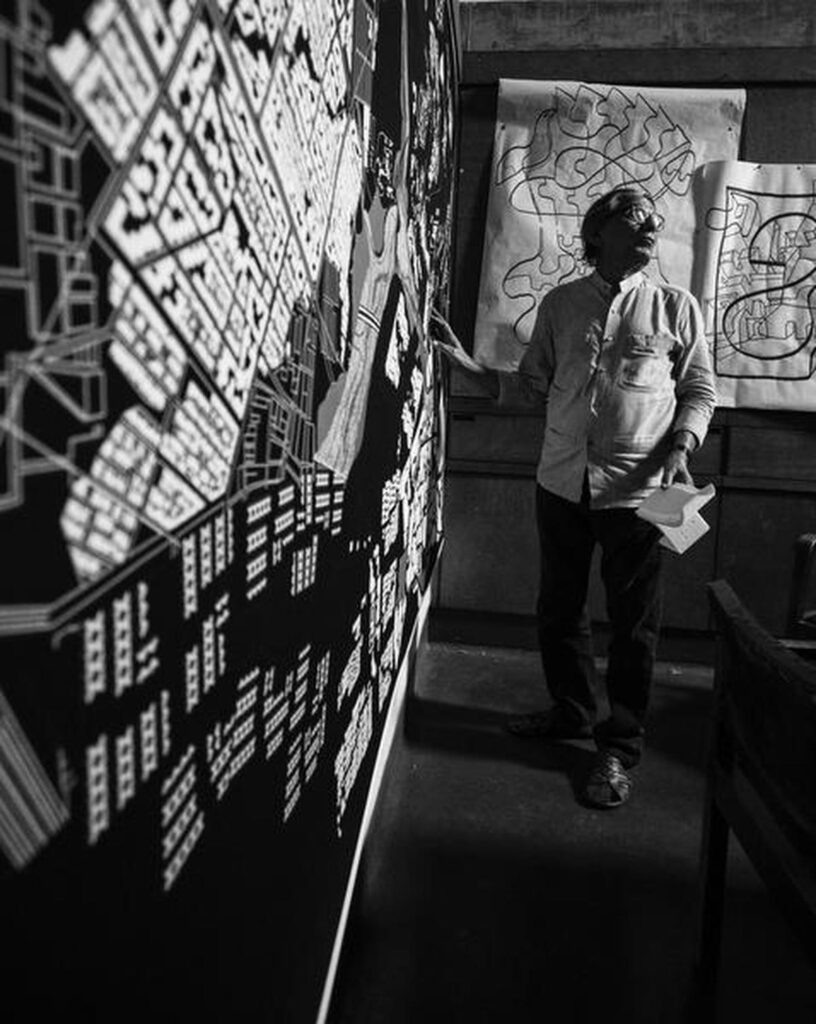

Doshi is contemplative, preparing for a journey to Shanghai with curator-granddaughter Khushnu Panthaki Hoof. ‘Celebrating Habitat—The Real, the Virtual and the Imaginary’, a retrospective of his oeuvre spanning seven decades, is to be exhibited at the Power Station of Art in July. “It’s probably the first retrospective of an Indian architect in an art gallery museum in China,” says Hoof.

The exhibition will include life-sized images of Aranya, an affordable housing colony in Indore for which Doshi conjured up Lego-like blocks to play with, illusive models of atelier Sangath and his home, of Amdavad ni Gufa, and several other projects. “The full-scale models create a new way for visitors to experience reality and illusion, like a theatre of memories and ideas,” says Hoof. “Apart from drawings and large-scale photographic installations, several finely-crafted wooden architectural models, furniture, miniature paintings, and brass hardware designed by Doshi will be on display.”

Also Read:

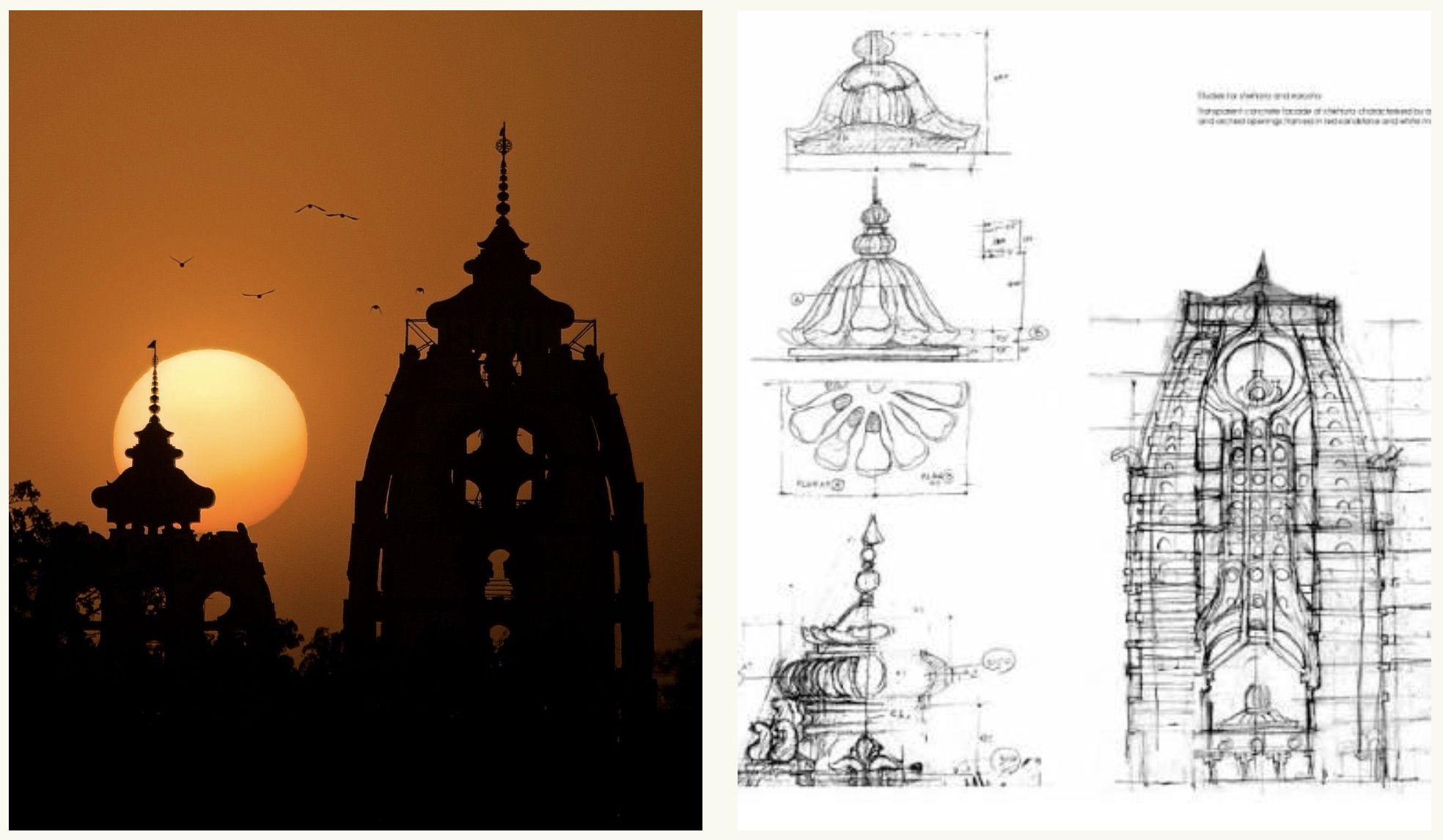

“Celebration is an integral part of our life in India,” Doshi says, “You will discover there are festivals all through the year—there is music, singing, dancing, people gather on the streets, there are processions, colourful clothes and sweets, we visit the shrine and have social gatherings and much more. It creates a community bond and a feeling of togetherness. But over the past few years, I see that this is not happening as often. Public spaces and city streets are getting congested with cars. Modern life is becoming more hectic and busy. Are we losing our connection with nature and our shared community values? If we look at our history, spaces like verandahs, inner courtyards, under the trees, pedestrian streets, plinths and terraces were the spaces for community gatherings. We need to connect with nature again and inhabit these kinds of informal porous spaces. Buildings are the background and containers for celebration and need to be sensitively designed to resonate this spirit.”

Stories and myths

A young architect walks in to discuss a drawing. It’s a reimagined streetscape of colourful bazaar streets of Jaipur. It depicts a biodiversity of life on the street, a few camels, trees, and a few cars. “I was brought up with stories and myths, which continue to dominate my life. As a child, walking through mixed-use streets in Pune, I learnt cooperation, tolerance, interdependence and patience. My grandfather’s home grew organically, first one floor, then more floors and rooms added over time. It was like a maze with a courtyard at the centre and many staircases. Buildings to me are living beings and extensions to life. I lived in a joint family, with birth, celebration, death and marriages happening simultaneously. I realised that any creative process is one of sarjan and visarjan . It is a constant cycle of creation, dissolution and renewal.”

My memories of Madurai, Ajanta-Ellora, Fatehpur Sikri, Sarkhej and the cities of Rajasthan continue to guide me.

In 1952, a young Doshi ventured across the seas to apprentice with legendary architect Le Corbusier in Paris and later collaborate with him for projects in Ahmedabad.

“I had no formal training in architecture. Looking back, it gave me freedom from the rules and dogmas ingrained in universities. I recall boarding a ship to London and then to Le Corbusier’s office in Paris. Working on projects at 35 Rue de Sevres, I understood what Corbusier meant when he spoke of a pact with nature and the spirit of diversity and porosity. These are the principles I learnt. Yet, my work is different, and based on my childhood experiences and journeys to different parts of the world.”

Like a yogi

“My memories of Madurai, Ajanta-Ellora, Fatehpur Sikri, Sarkhej and the cities of Rajasthan continue to guide me. Later, in contrast, working with Louis Kahn on the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, I observed his monastic spirit to search for the essence and the sacred, like an Indian yogi. Both Le Corbusier and Kahn, though with different approaches, were significant influences in my life, while my childhood remains the grounding from which many of my ideas and references emerged.”

A large poster of the retrospective adorns the wall in front of me. Looking at well-crafted fragments of models placed randomly on the table, Doshi explains the motivation behind the retrospective. “When we are sensitised, we become more aware of our environment, with all our senses. In the Shanghai exhibition, architecture is brought into the gallery. It creates a new awareness of how we inhabit spaces and buildings, light and sound. The retrospective is not really about me or my projects—it is about conveying my vision and ideas of what a city or a village or a home can be. I do hope the retrospective becomes an occasion to raise fundamental questions.”

“When I started the School of Architecture in Ahmedabad in 1962, the idea was to question these aspects. At the Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology (CEPT), we created an inter-disciplinary curriculum, suited to our climate, ethos, people and circumstances. We learn from travels to ancient cities. It creates deep-rooted understanding. Progress, however, implies we have to discover afresh, we cannot blindly imitate the past.”

Buildings are the background and containers for celebration and need to be designed to resonate this spirit.

Founded by Doshi with a few of his colleagues, CEPT has since become one of the premier institutions for environmental planning and design. The campus, designed by Doshi, has hosted some of the most respected thinkers and architects. “The design was inspired by the philosophy of Santiniketan and Rabindranath Tagore,” Doshi says. “The idea was to create a campus for learning with no doors, to celebrate the spirit of openness. The studios have natural light and ventilation and students of different disciplines work together. It was with similar ideas that I designed IIM-Bengaluru too.”

Smart cities

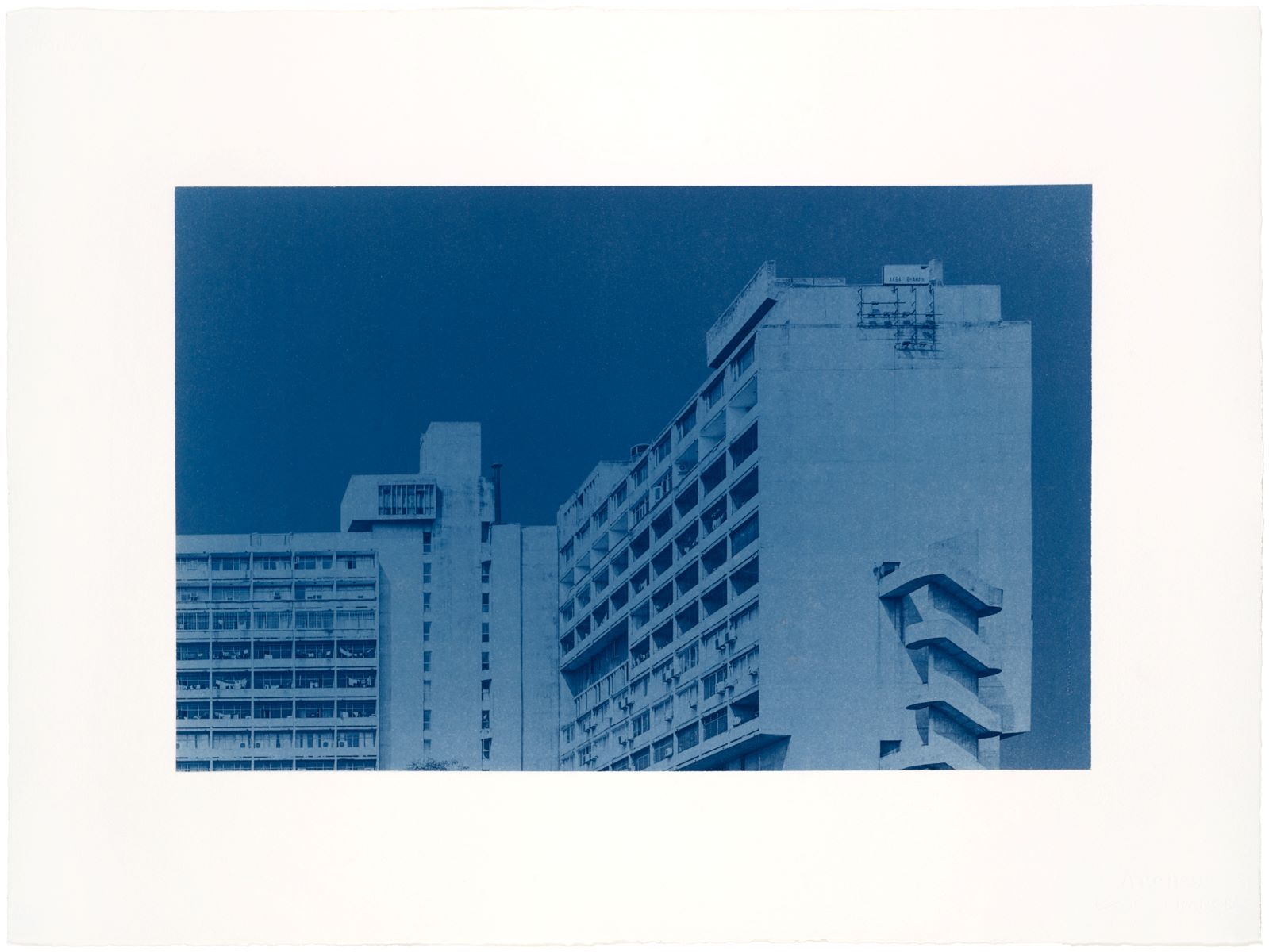

We discuss the contemporary predicament of Indian cities, with so much talk about smart cities. “The core of the city is its public spaces for citizen participation. Another important challenge is housing that is affordable to all. When I was working on Aranya, we evolved an incremental concept, like my grandfather’s house in Pune. Families could build and grow their houses in accordance with their needs and budget. It gave them a sense of belonging and identity. Each house was different.” The project received the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 1995.

“Similarly, while planning New Jaipur-Vidhyadhar Nagar city, the emphasis was on creating walkable neighbourhoods with vibrant public spaces for community participation. I think energy is the most important aspect for sustainable cities. Energy and inertia are in everything when we build a city. How can a city energise life? Does the city fulfil our aspirations? The next question is what kind of a place would you like it to be? Diversity is very important. And one has to feel secure and comfortable. Technology needs to facilitate these aspirations,” he says, referring to smart cities that appear more technological than human-centric.

It’s late in the evening and the Ahmedabad dusk transforms the shadows at Sangath as we prepare to leave. “Life is full of unexpected events, which do not fit into a norm. Architecture is a living energy-force that constantly evolves, taking deeper roots responding to the ecosystem,” Doshi says. “My life has been a journey with different kinds of experiences. I do not like rigid rules. Architecture should express diversity and the immeasurable. There are so many different ways of looking at things, infinite ways to enjoy and infinite ways to create. Celebration means that you create your own reality. My reality is about diversity and heterogeneous homogeneity. I realise that life is intangible.”

—Born in Pune in 1927, Doshi studied at J.J. School of Architecture in Mumbai

—His studio Vastu-Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design is known for designing low-cost housing, and city planning

—Fellow of Royal Institute of British Architects, and has been on the selection committee for the Pritzker Prize, regarded as the Nobel Prize of architecture

—He makes an appearance in the Tamil film O Kadhal Kanmani (2015) and its Hindi remake Ok Jaanu (2017), as the heroine’s mentor

Also see:

Artes-Roots Collaborative is a think tank of architects, environmentalists , and artists based near Vedanthangal, Tamil Nadu, and South Goa. Roots is engaged in research, advocacy, and community-participatory sustainable projects that explore ecological landscapes of the future, war refugees, and climate change.

2 Responses

so true the tangible and the intangible the abstract and detail