Rahoul B Singh, Partner at RLDA, New Delhi pens down his thoughts in response to Snehanshu Mukherjee’s article, which was published in the October 2017 issue of Indian Architect and Builder.

Dear Snehanshu,

As promised some thoughts that I would like to share with you after reading your article, “How Crafting Architecture Builds Economic Resilience in the Construction Industry.”

At the outset, I have to lay bear that economic resilience can only be achieved through education and so that’s where my vote lies.

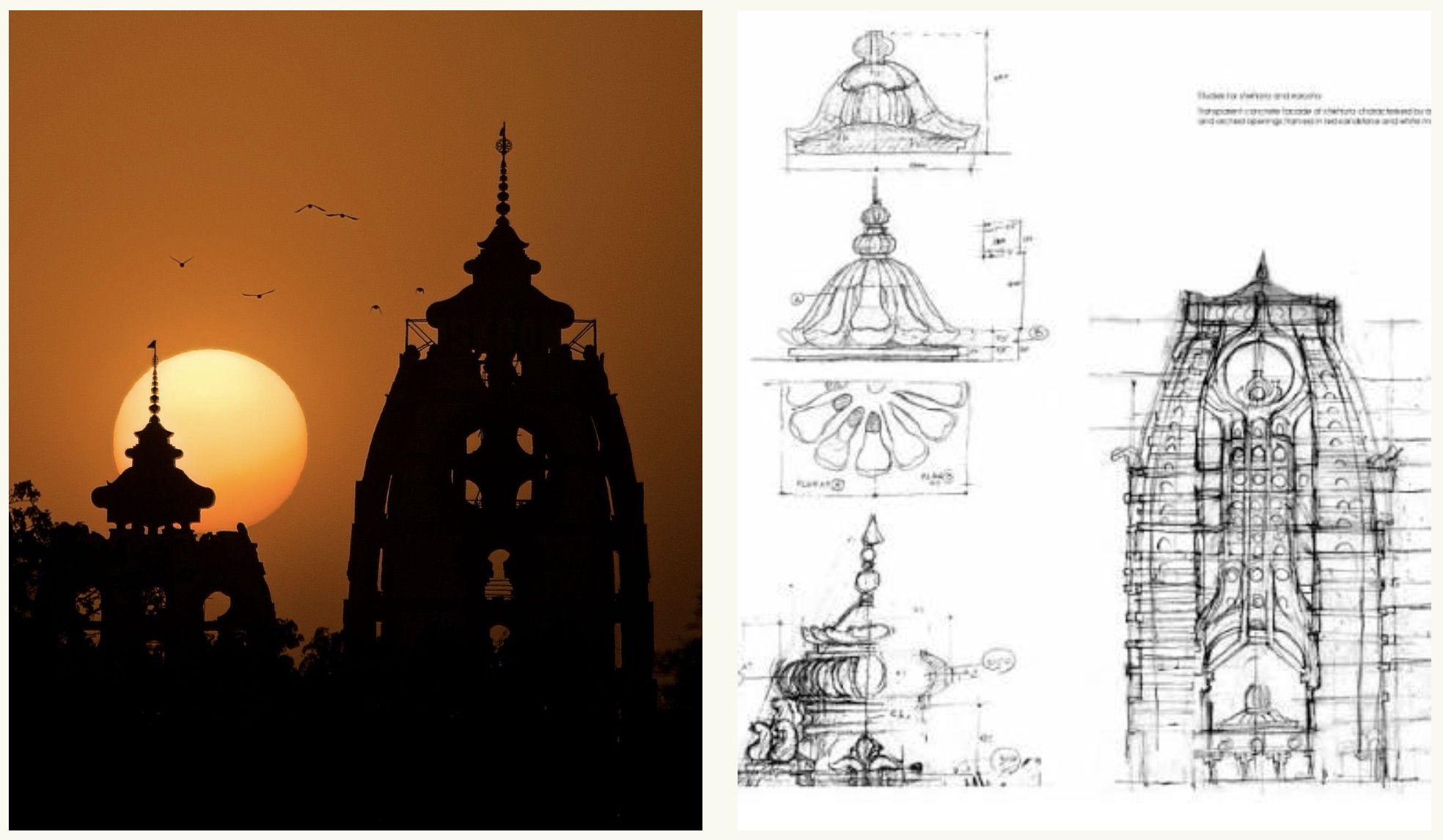

That said, you quite rightly point out Modern Architecture was an import and spread its wings over a highly developed crafts tradition.

It’s aesthetic traditions preceded the social construction that should have formed it, but the import served to give material form and aspiration to India’s Independence project. To that extent it served its role, and I think in hindsight, the Nehruvian project was not as bad as people have now made it out to be.

But craftsmanship, has a lot to do with making for the sake of making, the process is the purpose. The primordial relationship of eye, hand and material that through process has historically defined craftsmanship broke down after their inter relationship got segregated and dis-juncted. For example, historically, architecture was the largest “crafted” project. Painters, masons, sculptors all crafted the object. It’s not entirely accurate for example to describe Michelangelo as only an architect, sculptor or painter, he was all, other examples abound.

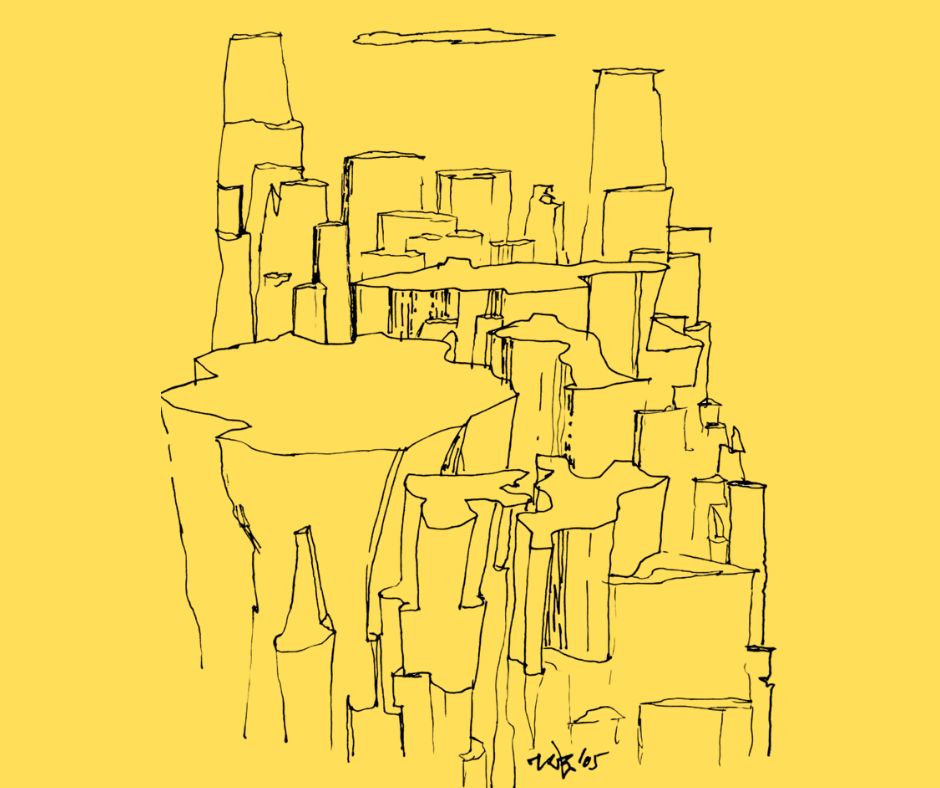

You can’t say the same about a modern day architect, who unlike musicians who make their music, no longer make their buildings, but at best represent them and specify them. The homogeneity of global practice and aspiration can in part be attributed to this development. The ease with which specifications can occur has transformed the act of making into one of designing and from there into one of specifying or better still curating.

The “dumbing down” of an architect’s ambition (yes, there are exceptions but they are far and few between) is only compounded by the comprehensibility associated with the transposition of global images. The architectural project as a constructed argument or point of view is fast ceasing to exist.

In fact, it’s a lost ground and the craftsman in the traditional sense of the word is the fall guy.

That said, I think there is a case that can be made for the role industrialisation and mass production have played in returning the act of making to the hands of the individual. The democratic impulse of technological development cannot be underestimated. What starts off in the hands of a select few percolates very quickly into the palms of many.

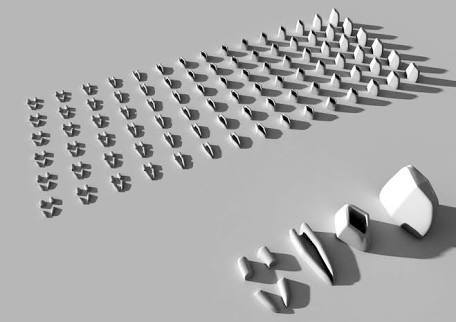

The digital craftsman as it were for lack of a better word is technologically enabled to design, fabricate and disseminate his / her craft from their desk. This has important ramifications for not only the profession of architecture, but also for the manner in which it is taught and practiced but, truth be told further alienates small craft communities who whose identity and livelihood depend on their craft.

I am not in a position to put value on which is a better or preferred mode but I will share with you three instances, two that I heard at talks at the recently concluded India Architecture Dialogues 2018 and one from the recently concluded exhibition of the Delhi Crafts Council that I visited.

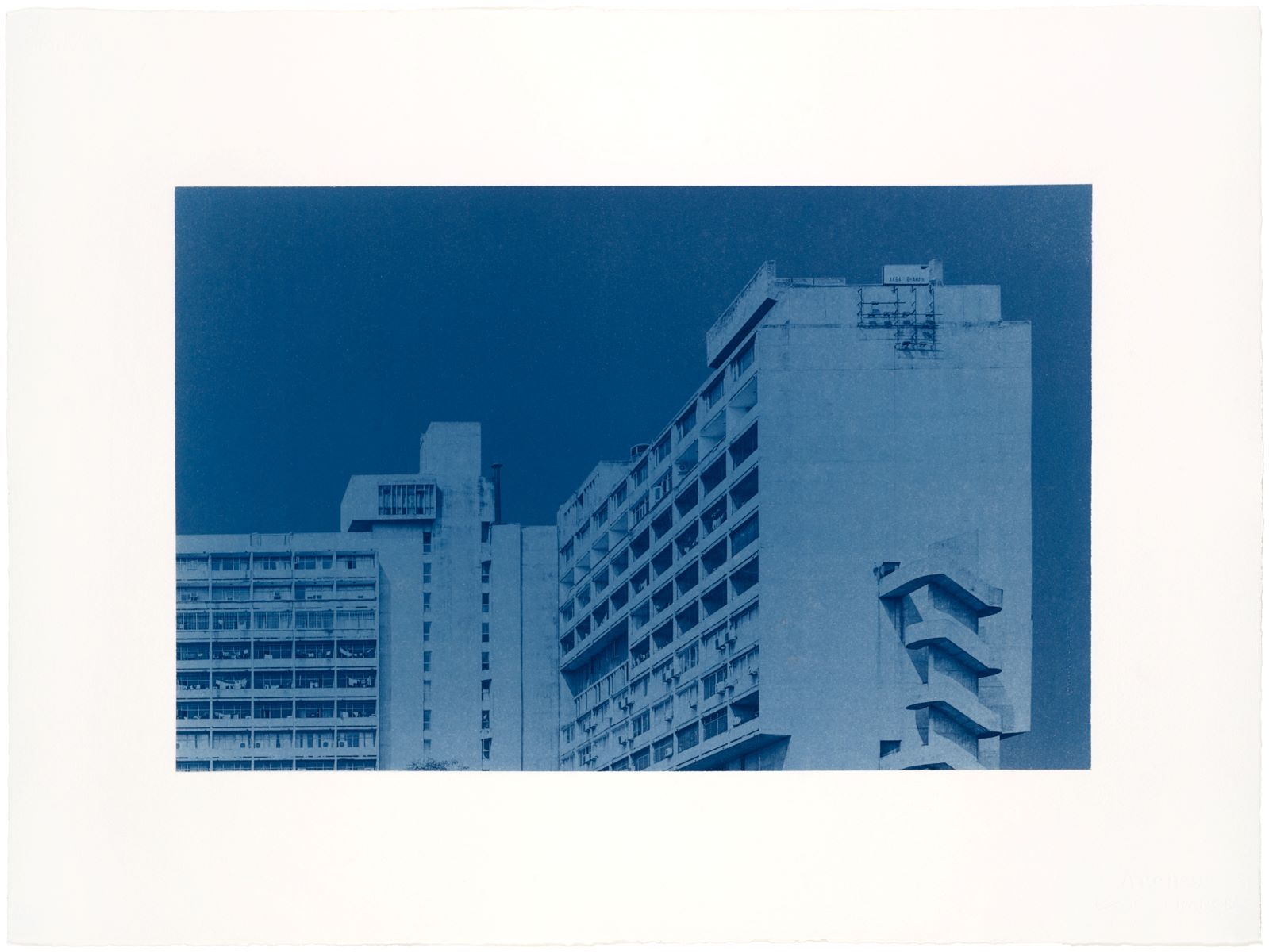

The first was by Helene Binet, the photographer – her photography is exquisite and I would encourage you to google her, however, she began her lecture with an apology for her work. She said that the photographs were not meant to be seen as projections, but rather as prints on the paper chosen by her and composed on the sheet by her. She said she sees herself as a craftsman where the tactile quality of the print is as much a part of the work as the image – it was very evident that she worked through her images, transposing a fleeting moment captured by her lens, printed in a darkroom (she shoots analogue) and subsequently materially manifest. Her work, is like that of the musician. She makes the image and through it gives it meaning.

Shajay Bhooshan, who heads a division of Zaha Hadid Architects, Zaha Hadid Code (ZHC) (you can google that too!) through computational analysis, parametric modelling and by focusing on architecture as it is consumed, represents the architectural object and that research in it will in time find either client or market. ZHC too are craftsman, they work through augmented reality and combine the tools of the hand and the machine to produce what they feel would best represent exigencies of the moment.

And lastly, the Delhi Crafts Council (DCC) just celebrated 50 years with an exhibition and sale of crafted objects at the India Habitat Center – designers, collaborated with craftsman to produce objects for use in contemporary living – some of the stuff was really quite exquisite! But this was an attempt to find a market for the traditional crafts of India through the an avatar that represent contemporary desires and aesthetics. Ironically, its very similar to what ZHC is doing – material and form research aimed at the growing needs of a market or community.

I am not sure what it means to dislocate the product of a craftsman from the specific geography of its making. It’s well known that largely, specific crafts were developed in specific regions of the country to address specific needs and were initially consumed by the craftsman themselves and their communities. But, the dislocation of craft from the broader region of its making infuses in it new meaning, takes away immediate comprehensibility and creates the space for new imaginations.

This arbitrage, if you like is where I believe the opportunity lies and I see it as a positive development. Here’s why-

Crafts constructed communities.

United by a common need people developed skills, honed after years of repetitive use, which gave them an identity and a livelihood. These skills were then pooled together whenever any member of the community needed to build a house for example and so a system of mutual support and inter- dependence developed and a high degree of resilience was embedded ion the system.

The “export” in the arbitrage process occurred either when local products were romanticised, objectified and transported for their aesthetic value or when through their material and making exhibited a property that an equivalent industrialised product does not or cannot.

In architecture, however, the case is slightly different and I think it would be worth dwelling (no pun intended!) on it, albeit briefly.

Architecture represents the crafts collective – a number of different craftsmen collectively contribute to the built work, each bearing the imprint of a particular trade. Unfortunately, seldom do they or their communities get acknowledged for their contribution. This, at the outset is the first step in eroding the identity of a people associated with a particular trade and by extension region, but it gets worse.

Value in architecture is more often than not understood in relation to something that represents the “gold standard” and here lies the tragedy or conundrum – in the quest for “perfection” the work of the craftsman is posited against the exactitude of the mechanical process, relegating the the cultural processes of historical continuity, value in site specific bespoke, or the cumulative wisdom of knowledge accrued by doing an act repeatedly over the centuries to the back burner in favour of the predictability and efficiency of industrial processes.

Industrialisation did bring with it building types that are suited to industrial processes – airports, skyscrapers etc. and in doing so the nature prof patronage changed, dramatically, begging the question that if architecture is to be (continue being) the largest employers of craftsman, how would it gain systematic acceptance? Industrialisation after all carved out its own processes – the CPWD, the lists of standard specifications, tendering processes etc.

I think the question of economic resilience for craftsman lies there, but more of that (potentially later!)

Warmly,

Rahoul B. Singh

One Response