The 50s generation had brands like Bata, Binaca, Dalda, Lifebuoy, Sunlight and Vicks. In the early 60s, I was intimately involved in promoting two: Lifebuoy began my child-model career and Dalda ended it.

Modelling as a child gave me two insights that served me well as an architect:

- The Process is as important as the Product (The Lifebuoy advert).

- Form and Function ought to have a healthy relationship. (The Dalda advert).

Lifebuoy

Unilever’s Royal Disinfectant Soap entered India in 1895 and became famous as Lifebuoy. Its advertising over a century centred on its ability to kill germs—an argument reinforced by its distinct carbolic aroma. Unilever’s advertising wing was Lintas in Bombay, where my father was the Art Director.

One weekend morning, my father drove home from the office, saying I should pack my swimming trunks as we were going to Juhu Beach. I jump up and jump in, no questions asked. There was another boy of my age in the car and a photographer. The boy was a child model for Lifebuoy Soap, and they were going for a photo shoot in the sea with him frolicking in the water. The photographer suggested that my father bring me along to be the boy’s playmate to increase the chances of the model frolicking. I am told none of this.

All I did at the beach was run into the waves with the child model trying to keep up. We had a spectacular time, splashing in the water and ripping into incoming waves. I was oblivious to adults lurking at the periphery. In the studio, the photographer realizes that the joy on my face far exceeded the child model’s. That was expected as he was conscious of being photographed for an advertisement while I was only conscious of our fun with incoming waves. One was aware of the product, and the other, being oblivious, was steeped in the joyous process.

The modelling world is ruthless; the other child was dropped, and I became the new favourite. Soon, I was featured in nationwide dailies in several languages with my eyebrows shaped in my photoshopped face before Photoshop existed.

Lifebuoy hai jahan, tandarusti hai vahan! But that red soap was nowhere in sight that wonderful morning we frolicked at sea.

Dalda

Desi Ghee (clarified butter) was expensive, so Hussein Dada imported a cheaper synthetic vanaspati into India in the 1930s. He called it Dada Vanaspati. When Hindustan Lever began manufacturing it in India, they requested L be added to the name. Dalda was born in India and Pakistan in 1937.

Kishorlal Mashruwala, an ardent opponent of Dalda, wanted it banned. The day Gandhi died, he mailed a letter to Jawaharlal Nehru to conduct a National Opinion Poll to appease Dalda’s opponents. The results were inconclusive, so Nehru set up a committee (a government ploy to take no decision). The year Mashruwala died, I was born: a Dalda-promoting repeat child model.

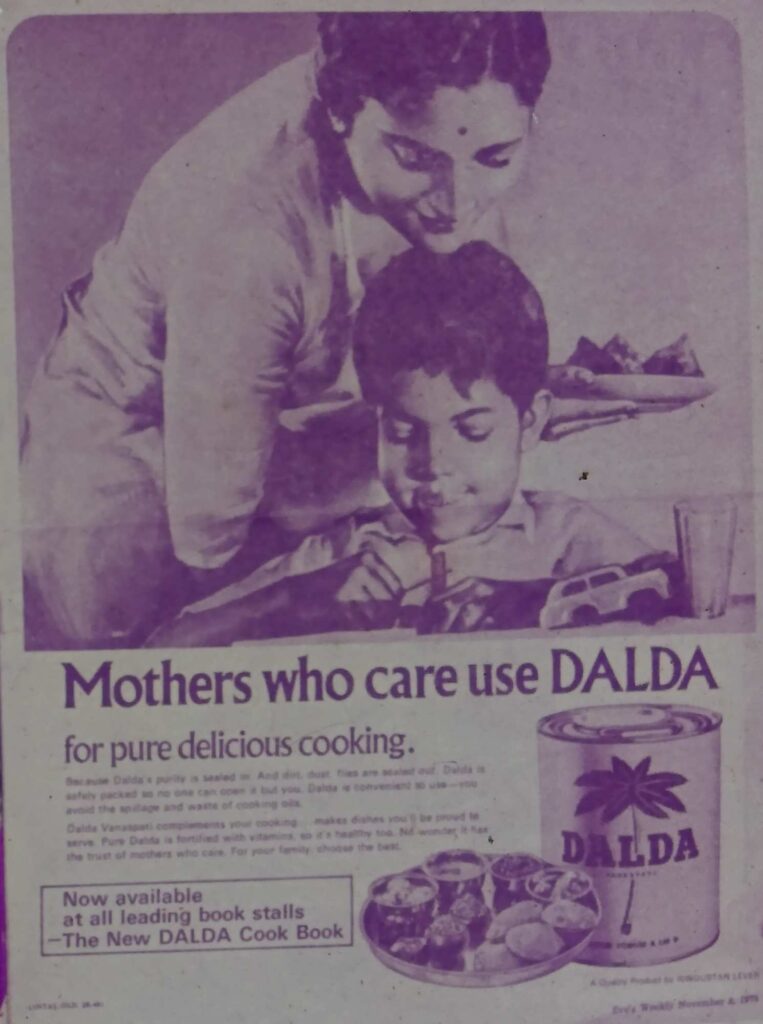

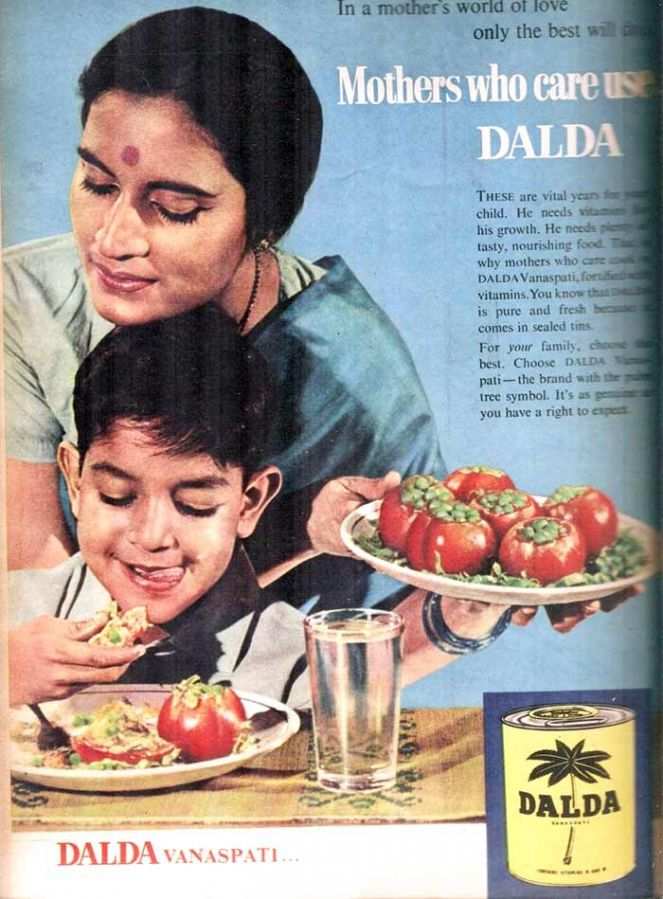

Lintas would give me a Meccano set to play with, and soon, the future architect would be so engrossed that he would be the photographer’s delight. After several iterations, someone noticed that I had a habit of sticking my tongue out, and hence, a plate of food supposedly cooked with Dalda ought to be in front of me.

But I spoiled that photoshoot. I was asked to gaze at a morsel in my hand, with the rest of the delicacy artfully arranged on a plate. I could ignore the lady’s chin resting on my head, a photogenic stranger posing as my mother as artfully as the tomato was posing on my plate. The only person not posing was me, as the tomato truly transfixed me. It was irresistible. Though not in the script, I decided to take a bite. As the tomato touched my lips, all hell broke loose. People rushed to prevent me from eating, spoiling my meal, wiping my lips. I insisted on eating it, unaware that the tomato had been coated with petroleum jelly to glisten (3-D photoshopping) and was inedible.

The form of the seductive tomatoes was not serving the function of satiating your appetite but instead instigating it. The target organ was not the mouth but the eyes to make you drool for Dalda. The function of propaganda had replaced the natural function. The form-function disjunction has made me impervious to Iconic reproductions in glossy magazines.

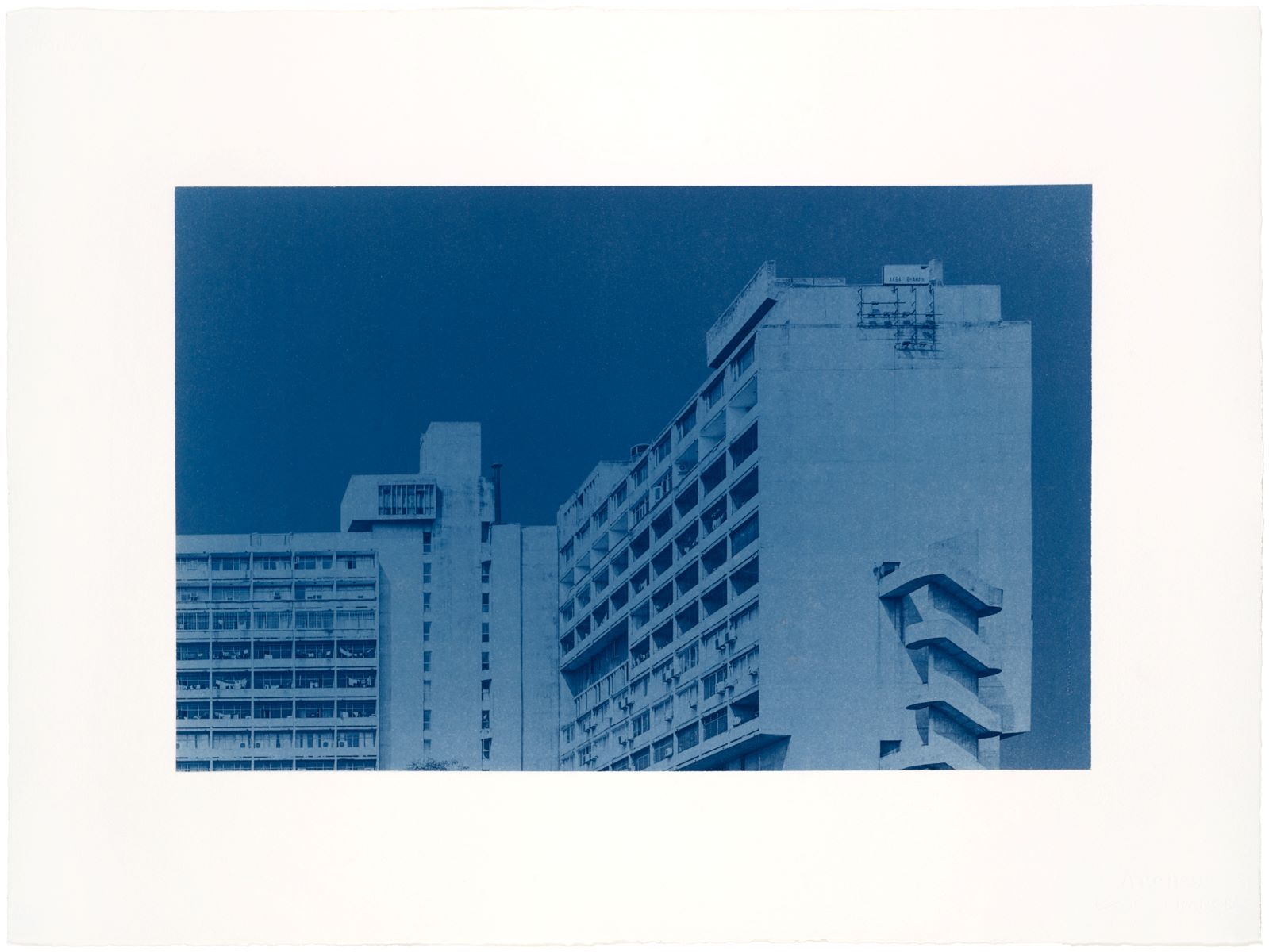

Architecture is found not in photogenic images but in memorable visits.

The enticing tomato was not edible, just as the lady was neither my mother nor Dalda ghee. Dalda is hydrogenated fat. Oils are forcibly hydrogenated to increase their shelf life, forming trans fats and manufactured fats that are bad for health. The US FDA had ordered removing trans fats from all processed foods. Vanaspati is only wannabe-ghee. We didn’t know then, but Gandhi was right, and Nehru was wrong.

Me disrupting the photoshoot and insisting I eat that seductive tomato and not the unvarnished substitute they offered me deemed me unmanageable. It ended my child-modelling career. However, in the 70s, Lintas revived my Dalda advertisement and reran it. I guess they ran out of child models who were as entranced by tomatoes as I was. There is no redness as red as the memory of that redness (recalling William Carlos Williams).

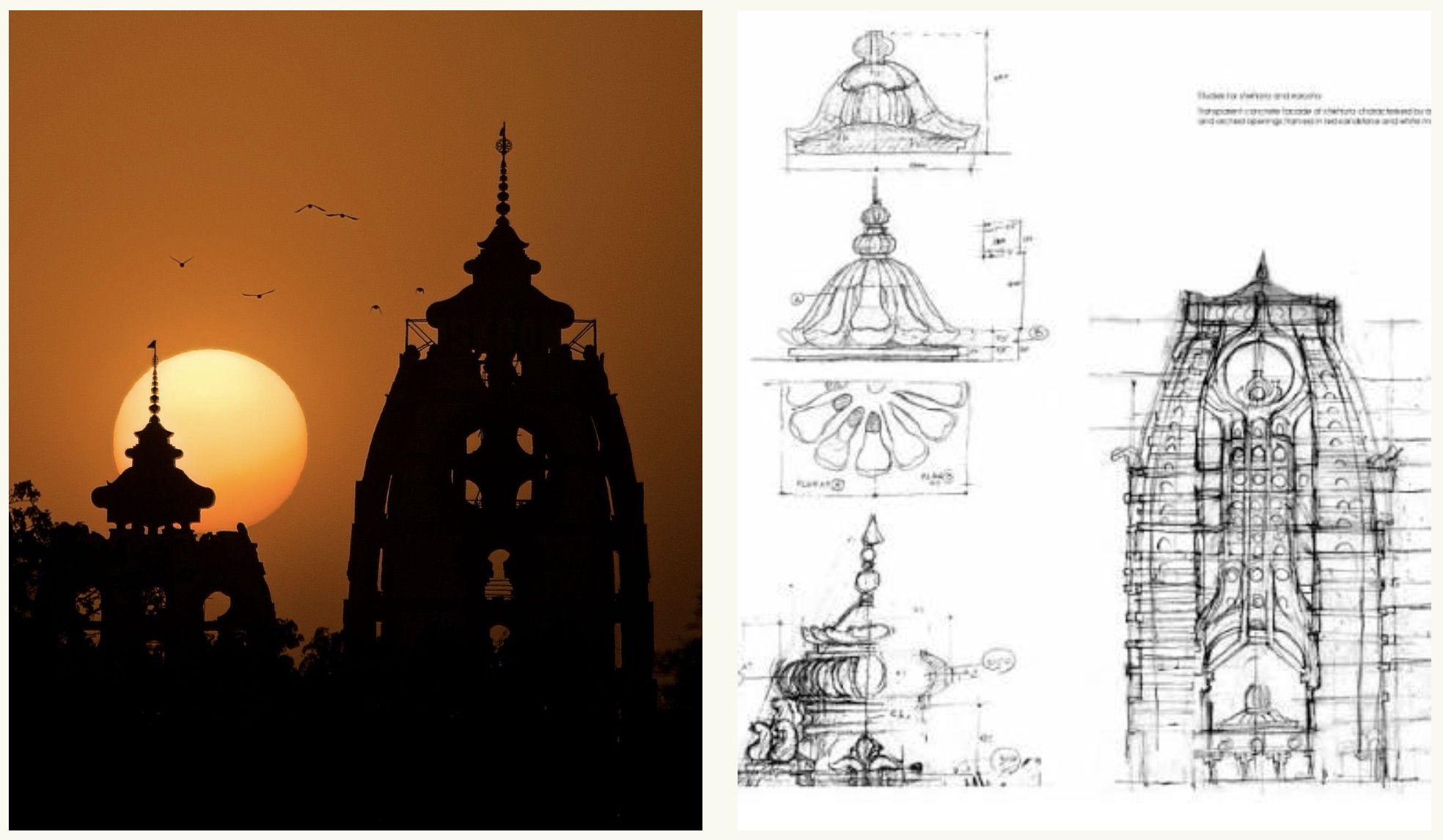

The pseudo-ghee carries on. In Pakistan, with the Eid jingle jahan mamta wahan Dalda (I can still feel the weight of my pseudo-mother’s chin on my dishevelled head) and in India, with Bhajan se Bhojan Tak Jagannath Rath Yatra prasad being distributed in Dalda bottles as devotees hold Dalda fans. They are thoughtfully provided with Divya Darshan: telescopic Dalda bottles to catch a glimpse of their gods. Images are closer than they appear; trans fats speed your journey into the afterlife.

Author’s Note: One Dalda advert shows a love of making things and the other of food. Little wonder the child grew up to author a series on Alimentative Architecture (An Architect Eats…) that resumes this year.

One Response

Very interesting and informative article.

Wonderful.