THE ARCHITECT AS A CRAFTSPERSON

An article I read recently made me think again about the obsession with creative freedom among architects. Among other things, the writer asked why architects chafe so much at the constraints on form making that environmental concerns impose. After all, more severe limits are placed on design by cost, plot size, and client taste.

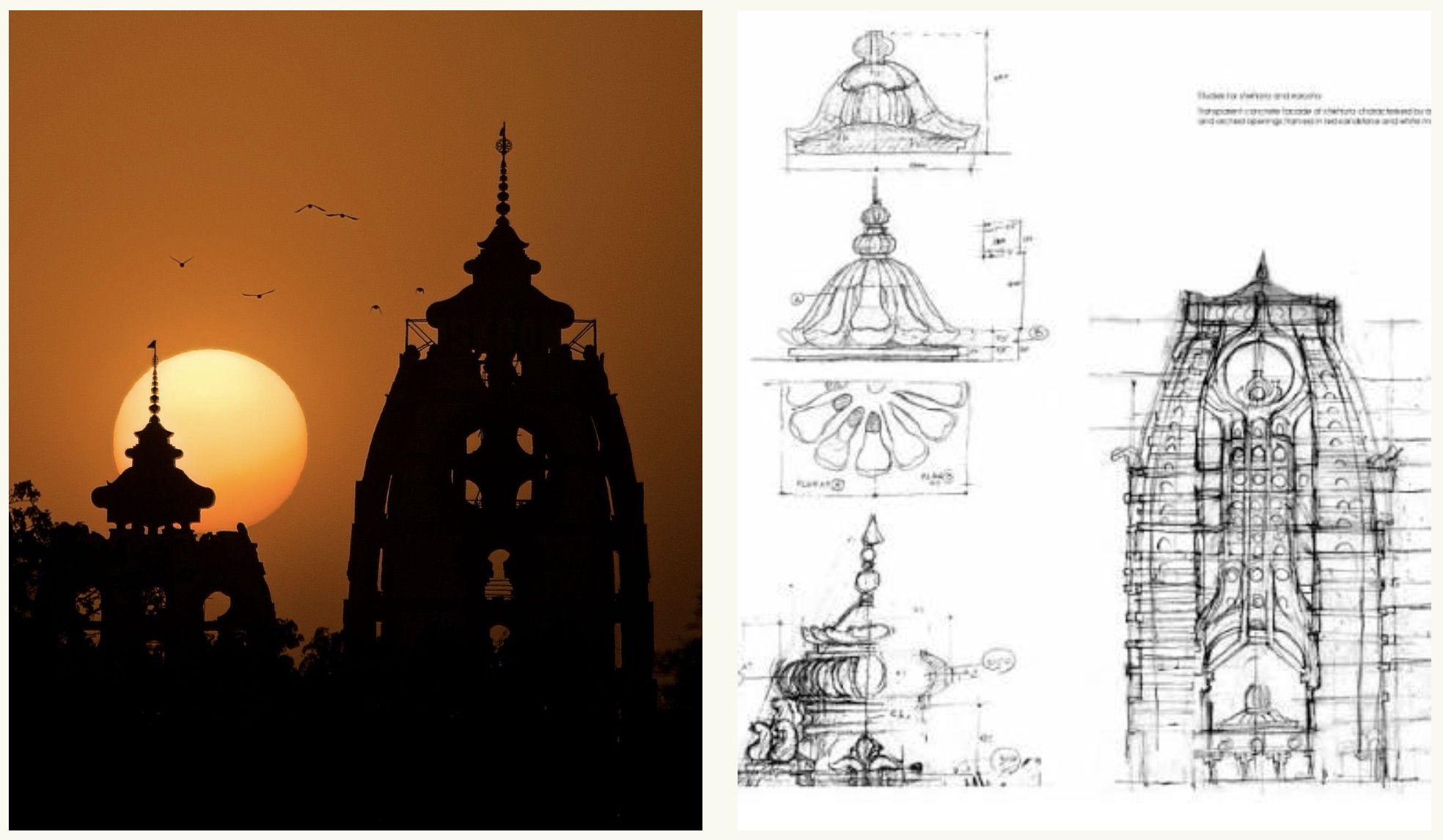

I feel that it will benefit everyone tremendously if we begin by thinking of architecture as a craft (in the traditional sense) before we think of it as an art. Creativity is central to craft. But craft the way it has been practiced traditionally is accepting of the everyday reality it is embedded in. In fact, the reason for its existence is clearly understood to be the everyday reality around it. The craftsperson takes it for granted that his or her skill and vision have emerged out of people’s real needs for clothes, products, shelter. The craftsperson does not need to see himself or herself standing outside society to feel legitimate as a creative person.

By contrast, the modern architect is conditioned to think that a blank slate and a blank cheque (in terms of money, creative decision making power, ecological footprint) are necessary for true creativity. No wonder architects complain such a lot about the constraints of reality in private and in public, crudely or with sophistication. Funnily, the complaints can be that their budgets are too small, but also that people have too much money and too little taste. They are also often that environmental regulations are such a pain: how beautiful that house would have looked on that steep slope (or ‘floating’ over the river on stilts)!

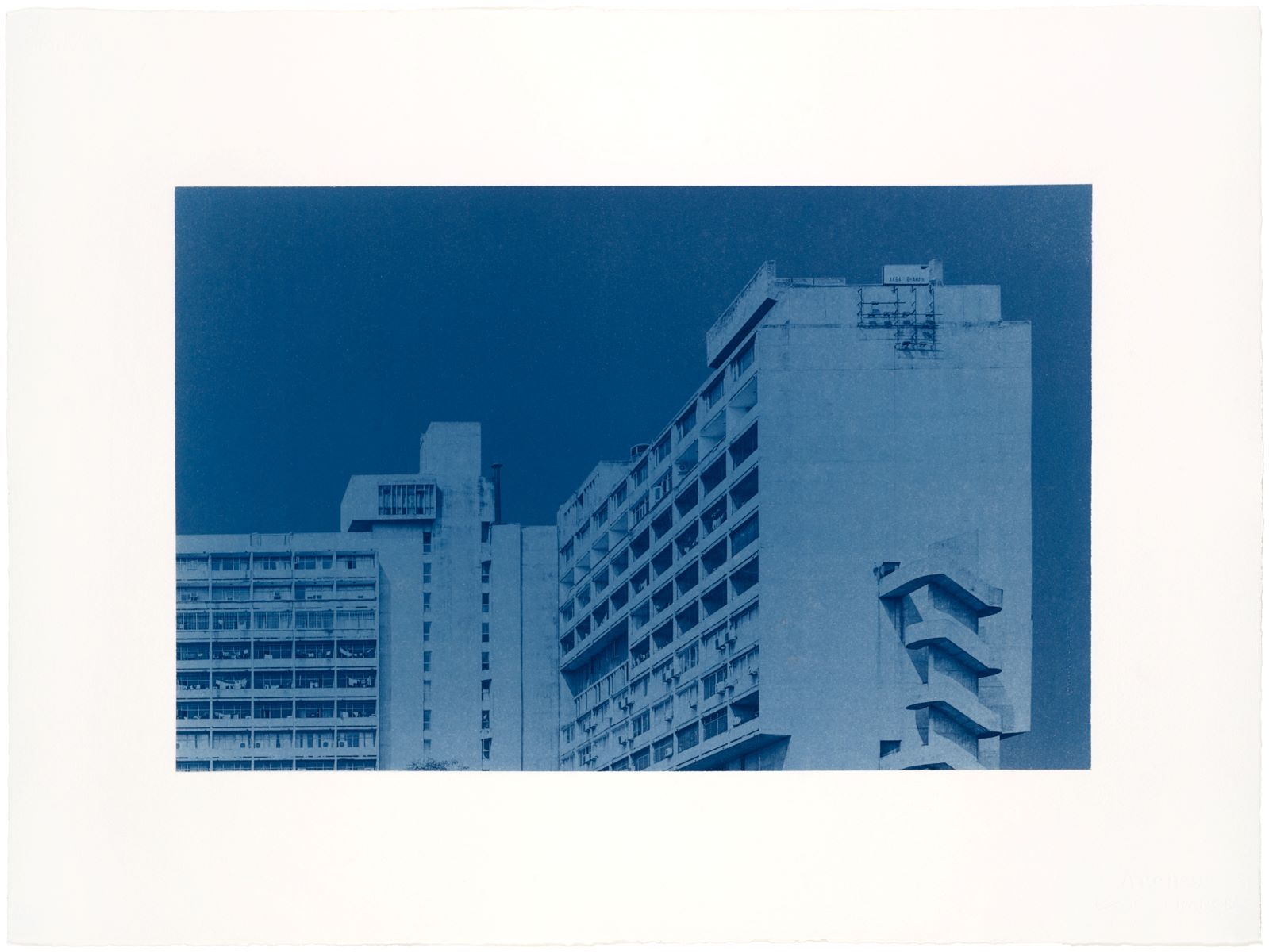

If the architect works like an eternal outsider, it is no surprise that architecture is blamed for failing to create a sense of place, and for being careless about its own environmental impact. Both problems are related. Creating a sense of place requires a sense of empathy with what people need to feel good in public or private. Caring about the ecological impact of your decisions also implies feeling like you are part of a team of people, other living beings and natural processes that dwell on the planet. Neither empathy with others nor feeling like a team member is possible if your training orients you towards standing out. Approached like this, the architect’s obsession with personal creativity (and glory) is much like that of the gifted forwards who compete with each other for personal glory in the hockey flick, Chak De. The team suffers, till the charismatic coach gets the ‘artists’ on track. Only, Team Earth has no Kabir Shah Rukh Khan in charge. (Of course, from a completely different perspective that may be a good thing, ultimately. But leave that for another time).