If truth be told, we don’t really want a place in the sun.

Neither, it seems, do we want a place in the shade. With the urban populace increasingly opting for glitzy, air-conditioned glass boxes, the idea of a public place – especially one that exists on the cusp of the built and the unbuilt – is rapidly devolving into a somewhat post-modern statement of exclusivity and affluence. When one can stand in the atrium inside a shopping mall, why would one choose to sit in the garden right outside it?

Somewhere between consumers who balk at the sun and producers who choose to shut it out, the relevance of deliberate spatial transition is eroding – at great cost to our resources as well our cultural ethos. It is clear that we either do not understand the importance of this deliberation, or are unable to implement it. On Charles Correa’s 87th birth anniversary, we turn to one of his most profound essays to rediscover this elusive element.

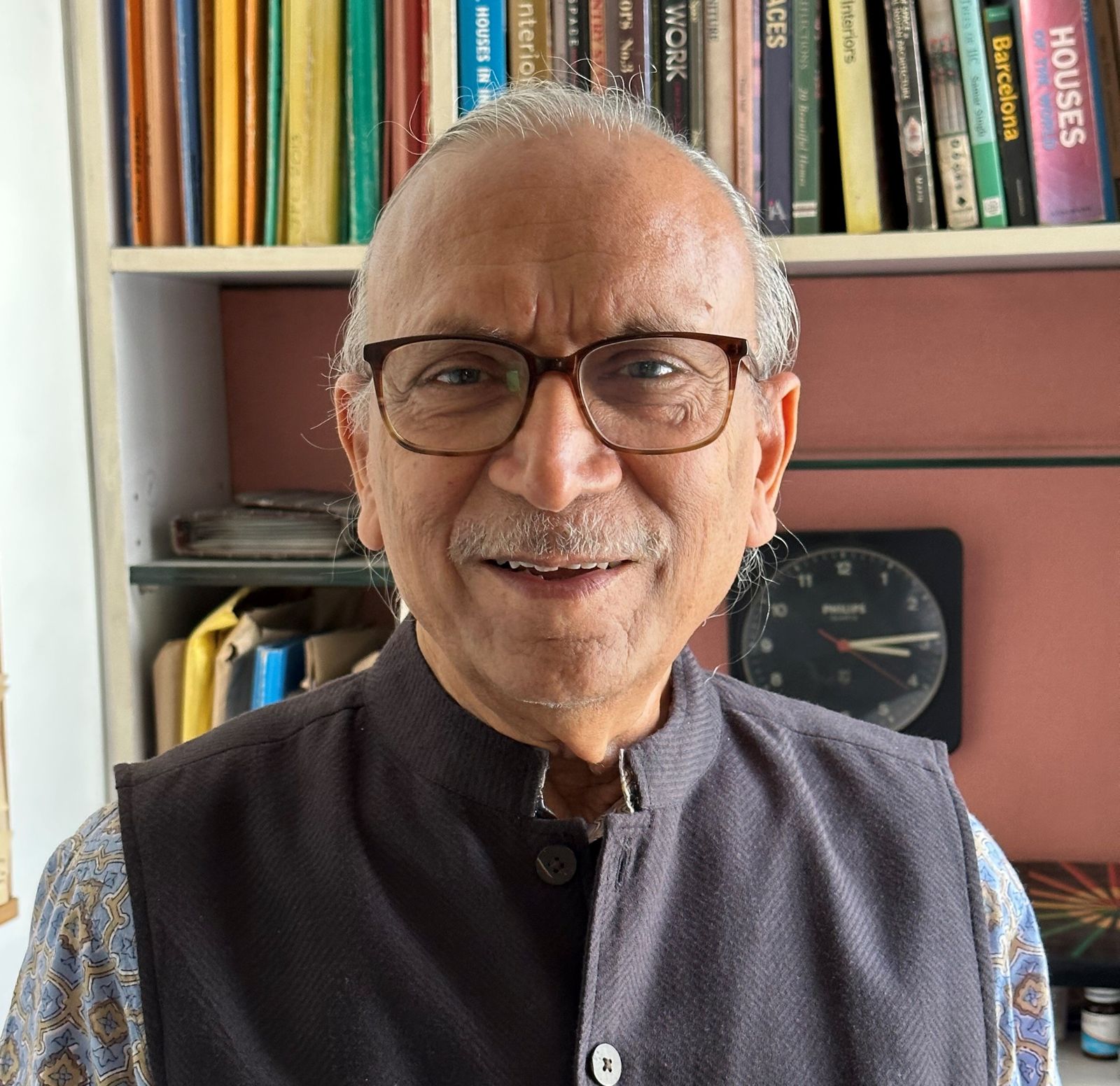

Charles Correa’s work took careful consideration of transitional spaces and their impact on Place-Making

The essay – which was originally delivered as a lecture in 1983 at the Royal Society of Arts, London – is somewhat metaphorically named A Place In The Sun, a misnomer that Correa acknowledges even as he prefaces his speech. Pondering over the unique challenges that practicing architecture in the Indian subcontinent poses – including, but not limited to, climatic constraints and cultural demands – Correa proceeded in this lecture to identify the three key issues that accompany the practice of architecture in the country, “The first concerns our relationship with built form; the second energy-passive architecture; and the third, housing the urban poor”.

“I shall try to relate them, one to the other, and set them in the context of a fourth issue,” he writes, “one that is crucial to India (indeed, to the entire developing world) – and that is, the nature of change.”

Correa speaks about this relationship to built form with great gusto – emphasizing the role that built spaces play in the Indian way of life, and how the adaptation to the tropical climate manifests itself through blurring the lines between built and unbuilt. He compares, even, the role that buildings play in popular iconography – describing how little red brick-boxes signify a schoolroom in the West, while a guru with his pupils sitting under a tree conveys the same to Indian sensibilities instead.

He further comments on how this marked difference in typological perceptions has always existed; indeed, the colonnades of the Greek temples lose their significance beyond an ornamental screen as we move northwards – their ability to create a leisurely atmosphere in a place of pause lost in the cold winds, where nothing but ‘boxes’ can comfortably thrive.

“This, of course, makes for a difference in our perception of what is architecturally desirable and significant. If one lives in a cold climate and is continuously involved in the production of boxes (and mutants thereof), then one becomes obsessed with the surface-patterning, the coding, the tattooing of those boxes.” he says, “and architectural photography, in journals and books, reinforces this obsession – since the printed image dramatizes two-dimensional patterns, but is quite incapable of communicating any sense of the ambient air.”

He puts special emphasis on this disconnect between the East and the West – and especially on the need of understanding the role that this ‘ambient air’ plays. His stance is clear – in a country like ours, with its balmy weather and abundant sunshine, it is inadvisable (if not completely illogical) to follow the conventions set down in snow-ravaged places. While the ‘tattooed two-dimensional patterns’ in journals and magazines look immensely appealing, they have little relevance to the physical space we inhabit.

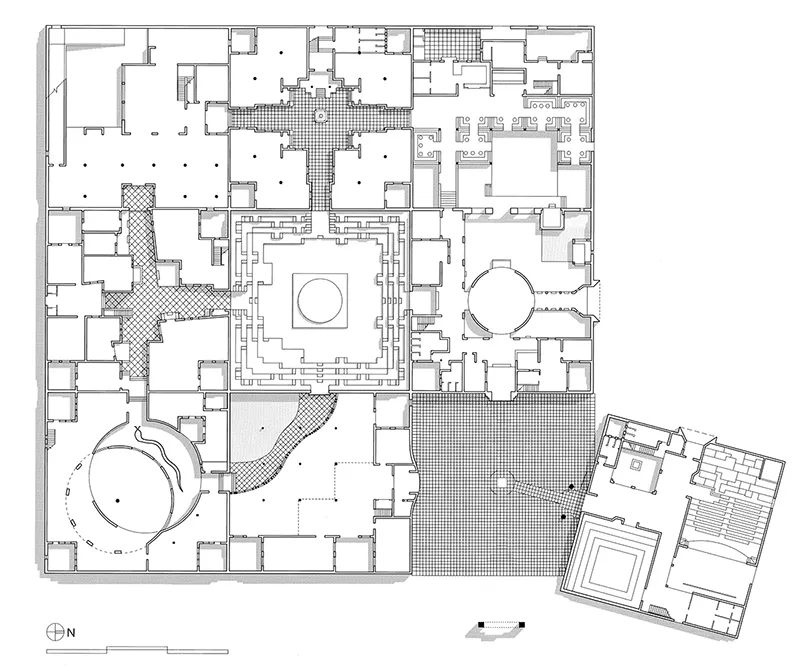

Correa continues, in his essay, to speak about understanding the nuance of this physical space, and harnessing what it offers us in greatest abundance – the sun. His discourse mentions the ritualistic role that sunlight plays in traditional eastern architecture – both as a constraint and as a design element – while also speaking about its mitigating effect in resource-strapped nations. His notion of providing even the poorest of the poor the sort of shelter that not only provides refuge from the elements, but derives tranquility from them, has been amply manifested in his various housing projects.

The housing projects undertaken by Charles Correa focused heavily on the livability of outdoor spaces and their potential for promoting social interaction

In fact, what we generally hold as his ‘signature’ elements – the brick-and-plaster materiality, the shaded courtyards, the occasional whimsical pop of colour – are not really his signatures at all. His architecture transcends mere elements, and embraces a philosophy instead – a philosophy that is rooted in asking the right questions, that aspires to a higher truth; the material expression and transitive nature are only a yield of it. When he speaks about the ‘two crucial roles that an architect must play’, he stresses upon the necessity of establishing an order and stimulating growth – although he refers specifically to the provision of housing, in this context, it is not difficult to see that these must become the guiding principles of all architectural endeavors in the country if we are to transcend the role of mere plan-makers.

Correa’s sensitivity towards context and culture has created a cohesive body of work that is its own identity and endorsement, and has gained a timeless quality despite its modernist origins. His buildings, in fact, embody the modernist revolution on the continent far more prominently than most contemporary steel and glass boxes in the metropolitans ever have, despite the former’s purported traditionalism. One must note, at this juncture, that modernism necessitates the fulfillment of function – which a blatant disregard of environmental exigencies cannot achieve.

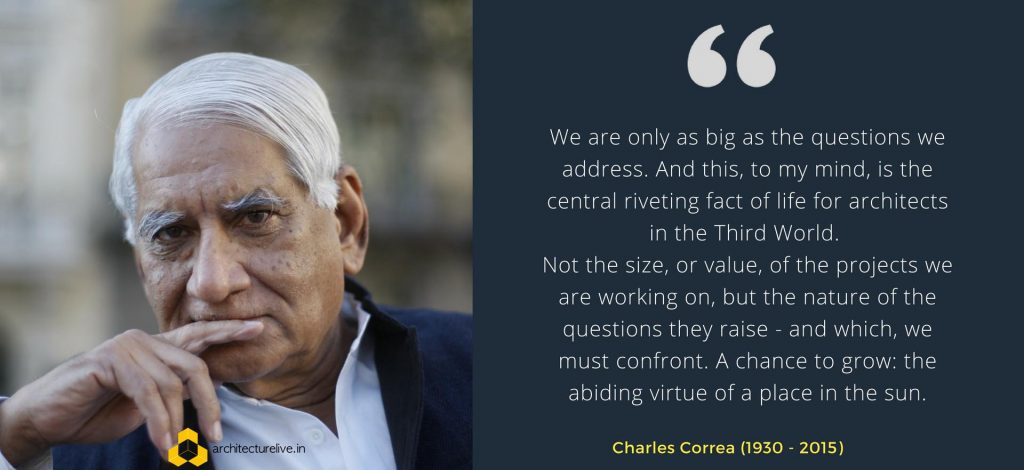

“‘There are no great men’, said Stendhal apropos of Napoleon, ‘there are merely great events.’ And, one could perhaps go further and say: there are great issues. For we are only as big as the questions we address. And this, to my mind, is the central riveting fact of life for architects in the Third World”, Correa wrote as a parting note, “Not the size, or value, of the projects we are working on, but the nature of the questions they raise – and which, we must confront. A chance to grow: the abiding virtue of a place in the sun.”

Now, more than ever, we must heed his words and strive to create this place in the sun – or shade, as it may be – independent of typical influences, determined in our own sense of purpose.

You can read A Place In The Sun and other essays by Charles Correa in his book A Place in the Shade published by Penguin Books.