On the 28th of May, 2023, the prime Minister of India inaugurated the new Indian Parliament building in New Delhi. Anyone watching the event and the hype preceding the day will have been wondering if it was the institution of the parliament or the edifice that was inaugurated; there seemed to be a concerted effort to blur the distinction.

As a legislative institution, the present parliament came into being in May of 2019 and will remain active until it is dissolved just before the next general election in 2024. Thus, the institution has a transient life and is periodically reconstituted and re-inaugurated after every election with a new mandate to debate, deliberate and legislate (not to rule) on behalf of ‘we the people’. The edifice, on the other hand, is the physical entity, a building identified with this institution and acquires an iconic stature as the symbolic representation of this institution and is relatively permanent. Relative because, though all public architectures are expected to have a long life, like all physical entities spanning centuries, these, too, are susceptible to decay. Also, all human institutions are also subject to change and evolution, requiring new accommodations. As these events are, by nature, infrequent, a celebratory inauguration may be an appropriate occasion for a reminder and restatement of the nature and purpose of the institutions they house.

On the 28th of May, 2023, it was the new edifice that was inaugurated and not the new institution. There have been differing opinions about whether a new building was really needed, costing a massive sum of money. The existing parliament building, built during the colonial period but still transcending its colonial association, has been well-etched in the popular psyche as a symbol of the new democratic India. Could we not have given it a new life? Could we not have appropriated a colonial legacy by adding a new layer of our own at much less cost to us? No doubt these questions will occupy future historians trying to interpret the motives, benevolent or otherwise, of the present powers that be. It is not my intention to wade into these waters. Nor is it my intention to critique the architectural merit or demerit of the new building as may be expected from an architectural critic like me.

The new building is a reality, fait accompli, and such critique can have only academic value.

What I do want to bring to the notice is an aspect of architecture not often understood by architects. Architecture is more than its functional, commercial or aesthetic self; it is a cultural construct. As such, it invariably gets entangled in the politics of culture, wherein the dominant culture often assumes itself to be the repository of truth. Our own colonial history itself is replete with numerous examples of architecture being appropriated for the purpose of defining imperial selfhood. Architecture and space, more than any other super-structural manifestation of a culture, have provided the site upon which such acts of identity formation have been played out. As Ian Baucom has noted;

Englishness has consistently been defined through appeals to the identity-endowing properties of place….as a Gothic cathedral, The Victoria Terminus, the Residency at Lucknow, a cricket field, a ruined country house, and a zone of riot…Englishness has been generally understood to reside within some type of imaginary, abstract or actual locale…to control, possess, order, and dis-order the nation’s and the empire’s spaces.[1]

What is crucial to remember is that while it did involve defining the “otherness” of the other in order to relegate it to a lower level of cultural hierarchy, it also involved, and more crucially so, defining the terrain for elaborating strategies for selfhood of the defining culture itself: the West. It is in this light that I want to view the new Parliament House and the rituals surrounding its inauguration as a possible projection of a cultural identity of the ruling dispensation that I find problematic on several counts.

One, elaborate rituals have been performed to indicate that there has been a transfer of power. Transfer of power from whom to who? Under the Indian constitution, the power to rule rests with the head of State, the President, who is also periodically elected. And no such transfer is in the offing yet. And when that happens, it will involve the new President, not the Prime Minister, as the recipient of the symbols of authority. Of course, the Prime Minister has all the right to preside over the inauguration of the edifice – the building- as he often inaugurates many important public facilities and other infrastructural projects. Yes! The edifice of the parliament may be more significant than an opera house or a dam. But the religious rituals involving spiritual symbolism blur the distinction between the edifice and the institution.

Two, an ancient tradition from the past has been harvested to lend the authenticity of the traditions to the projected self-image of the government. The Dharma-danda (sceptre) is a symbolic object associated with ancient India’s monarchical form of governance and was always used at the time of the coronation of the new ruler, but not as a symbol of authority to be passed on to the newly coronated ruler, as is done in the Western monarchies. The legend has it that after the coronation, the new king will loudly proclaim his sovereignty. But the Rajguru, the traditional repository of the spiritual, ethical and moral authority, would tap the sceptre on his head to remind him of the limits of his power. While in the Western tradition, where the Bishop hands the sceptre to the new monarch, it connotes that the power the king receives is divinely ordained. There is an implicit religious sanction to the authority so received.

The dharmic traditions of India, on the other hand, rightly recognised the dangers of absolute power and had built into the act of the transfer of power an element of warning to the sovereign that his power has limits and that he should at all times consult the Rajguru about the ethical, moral and spiritual consequences of all his decisions. All temporal power has limits. Historical evidence shows that all benevolent rulers accepted that. For example, my grandfather was a high-ranking official in the court of the Maharaja of Baroda, Sir Sayajirao Gaekwad. Once, when asked to report to the office at 7:30 in the morning for urgent consultation, he refused, saying that, at that time, he had to attend to a higher authority – his daily puja, which he shall not miss. The benevolent Maharaja immediately agreed and passed a note that Shree Mehta should never be disturbed at this time.

Thus far from a symbol of power, the sceptre symbolises the limits to power.

And finally, we are not a monarchy any more. A representative government is not a ruler whose power flows from heavenly divinity, nor do we have a Rajguru to place guards of limits against the absolute exercise of power. Instead, the authority (let us not use the word power) is given to the government, flows from the people, and is to be renewed every five years, never in perpetuity. The collective wisdom of the institution of the parliament replaces the wisdom of the Rajguru. The only similarity is that, like the king to the Rajguru, the government is also expected to consult the parliament at all times. Parliament – the institution – provides the guard rails and the checks and balances against the always possible encroachments of the government on the rights of civil society.

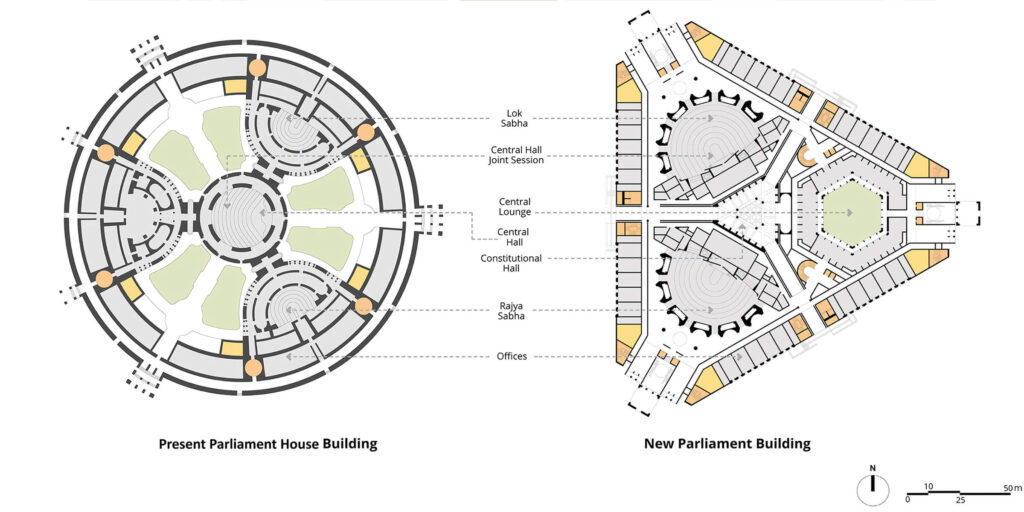

Our parliament did perform reasonably well during the first couple of decades after independence. And nobody can doubt that recently, it has not been functioning as it ideally should. Nevertheless, the potential is there and is embodied in the neutral circular form designed by architects Herbert Baker and Edwin Lutyens. The nation’s collective imagination connects the architecture of this edifice with the institution it embodies.

One cannot escape the nagging feeling that the events of the 28th of May, 2023 were designed to not only replace the old building with the new but also, in the process, fundamentally alter the popular imagination of what it represents.

Why was the symbol associated with the transfer of power, an event of spiritual significance, brought in to embellish the transfer of location, an occasion of mere temporal import? Is there a subliminal suggestion here that the real, more consequential transfer of power happens now and not in 1947? Are we to erase from our memory all history of the last 75 years and begin anew? Was this purpose built into the very conception of the new building? Is the occasion to inaugurate a new building -architecture – turned into a weapon in this war of cultures?

[1] Ian Boucom. Out of Place: Englishness, Empire, and the Locations of Identity. As quoted in Imperial Co-Histories. Ed. Julie F. Codell. 2003.

Featured Image: ANI

4 Responses

Jaimini Mehta has overlooked the fact parliament has two houses and that the Rajya Sabha, the upper house, continues without being dissolved.

No doubt the motive from the conception added by two egoistic individuals associated was to bring about change of culture as a hidden weaponry by one in power and for the other to disregard the ethics for personal gain.

इमारतों को बदलने से इतिहास नहीं बदलते.

Apart from exposing ignorance of the writer on the psychological and henceforth cultural impact in the long term of colonization(s) on the societies/nations/people (for that one needs an independent mind and not a mind that of a post colonial era colonial slave, irrational comparison/examples, but knowledge of his/her own culture and haritage, history of geopolitics and relation to/impacts on domestic politics – which includes regional politics- etc. and also all of this’s influence on architecture), this article, if read between the lines, throws light on “the frustration” of some other colleague’s work/talent appreciated by the democratically elected government/institution and his disapproval to it and the fact that it doesn’t matter at all.. in general it’s waste of time to read this article which has no honesty whatsoever.