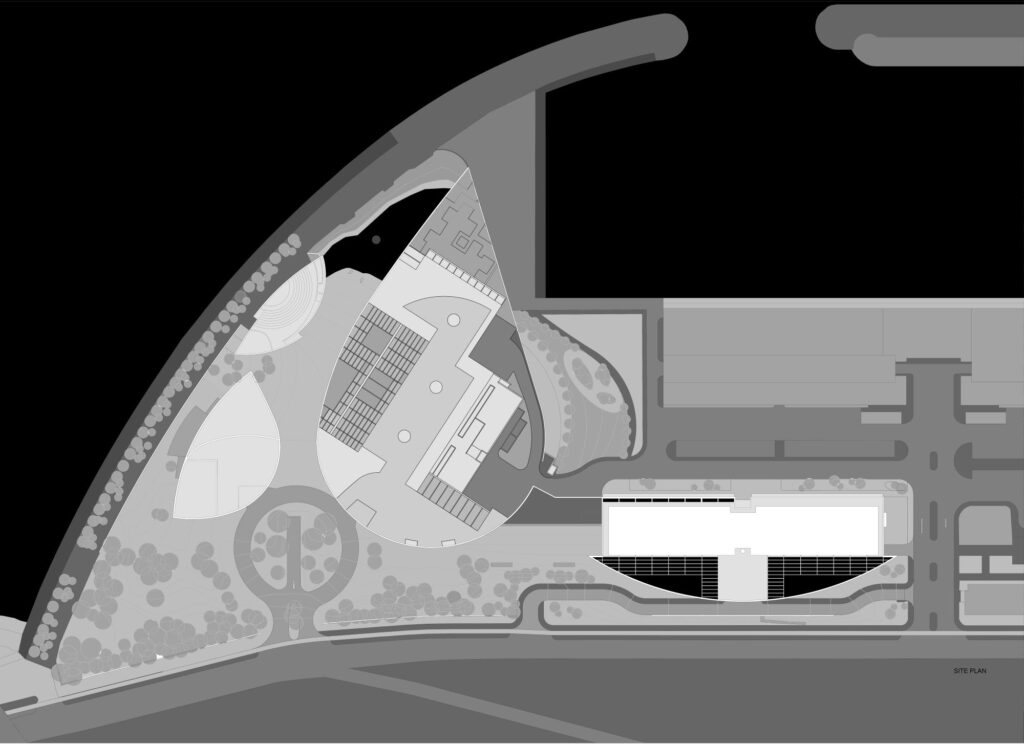

In the year 2007, the Champalimaud Foundation took an initiative to build the Cancer Research Centre on a beautiful site in Lisbon along River Tagus. It was designed by noted Indian architect Charles Correa.

By the time the Foundation decided to build a hospital for the cure of pancreatic cancer next to the Cancer Research Centre fourteen years later, Charles Correa had passed away. They approached architect Sachin Agshikar from Mumbai who had worked closely with Correa for eighteen years and served as his associate on the Research Centre. Agshikar was hired to conceptualise the overall building design alongside the US-based firm HDR for the internal planning, and Joao Nuno Laranjo from Portugal as the local architect.

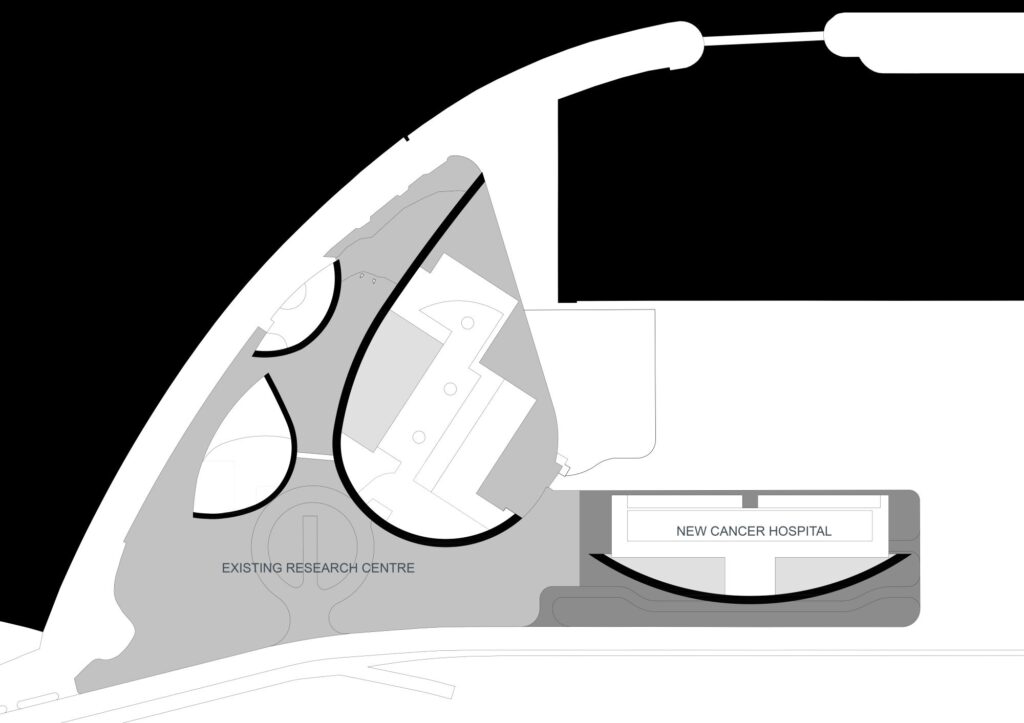

Compared to the 40,000 square meter plot on which the original research centre was built, the new plot was extremely small measuring merely 13,680 square meters. The new hospital had to functionally relate to its predecessor because some of the facilities in the original one were to be shared.

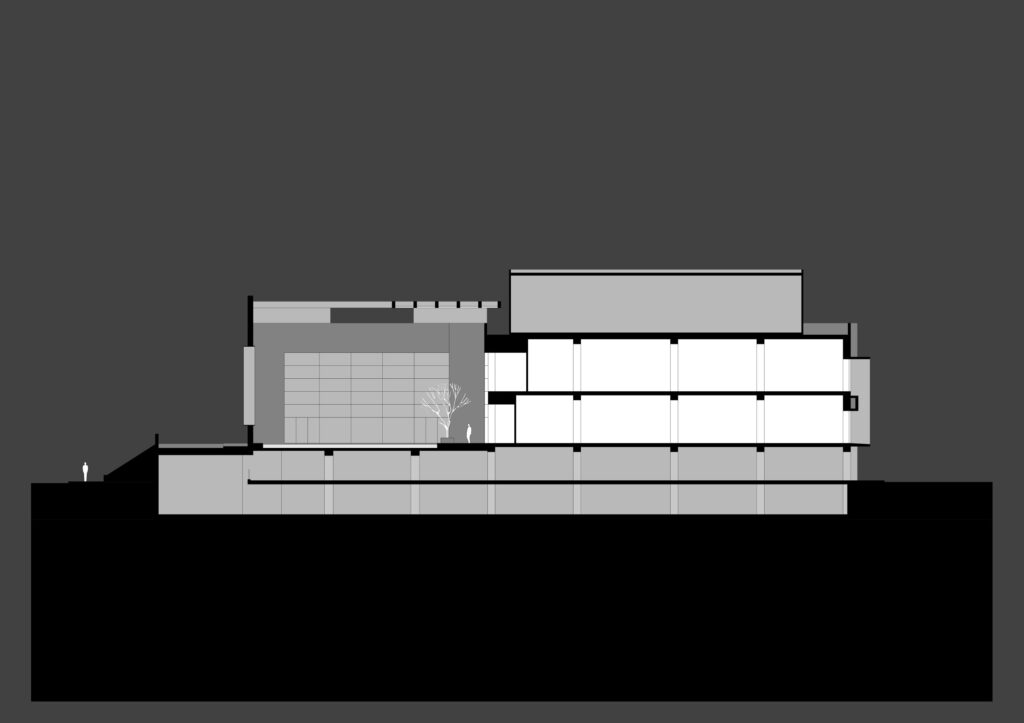

It seemed imperative to the architect that this new building be designed to blend seamlessly with the existing building mainly because they would be seen together as a single complex as one drove down the avenue. It was also important to maintain a low scale as the hospital had a much longer façade facing the avenue compared to Correa’s research centre. A floor higher would have made the new building overpowering.

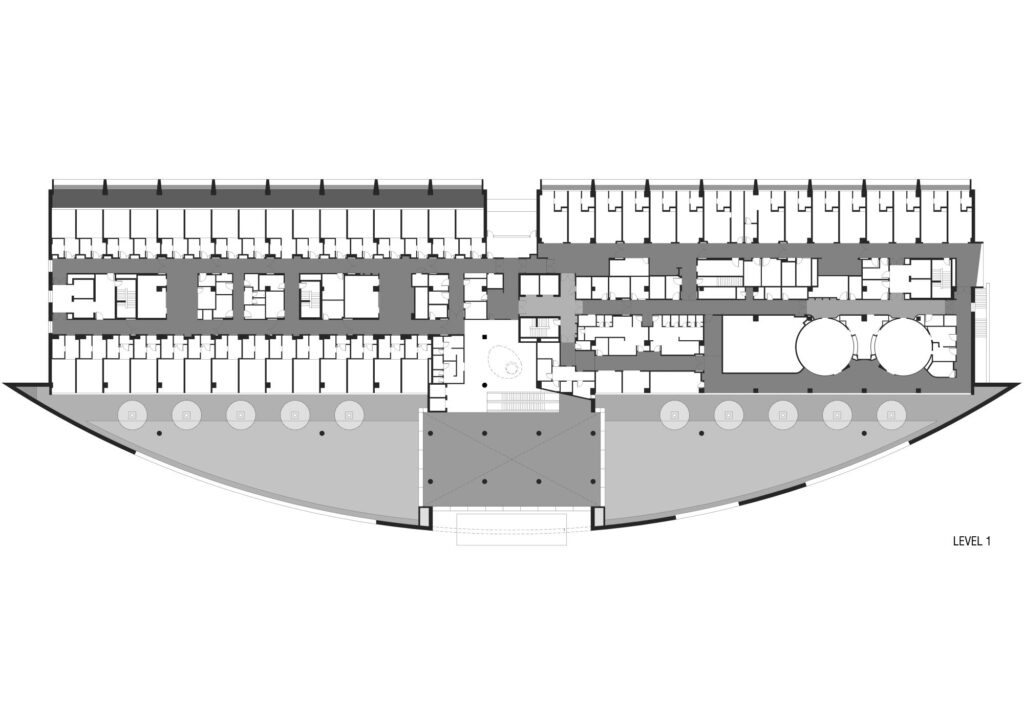

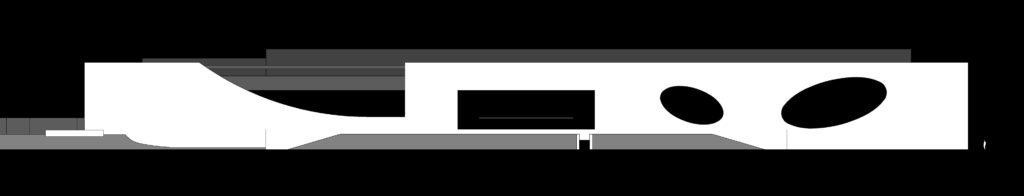

Since the buildings in the Research Center were characterised by a visually-dominant curved façade, the front of the new hospital building also has a gentle curved stone wall, 172 meters long. The wall is punctured with oval shaped cutouts on one side and a deep cut on the other side partly revealing the pergola-shaded courtyards beyond. The oval shapes were a conscious echo of some of the most dramatic gestures from the Research Center to ensure architectural continuity.

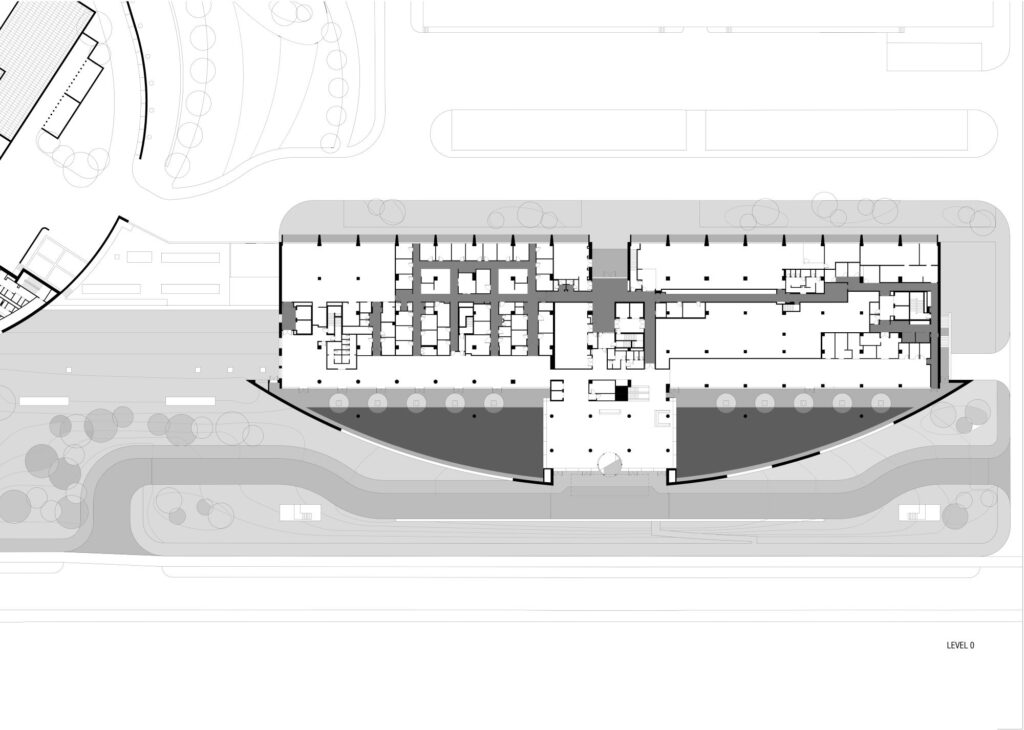

The driveway rising from the 0m level to the 3.5m lobby level is cleverly hidden behind a landscaped mound and a low wall. One passes through the revolving doors to enter a largely glazed double-height space that is flooded with natural light, creating an extremely positive feeling for the patients who came here with a sense of hope.

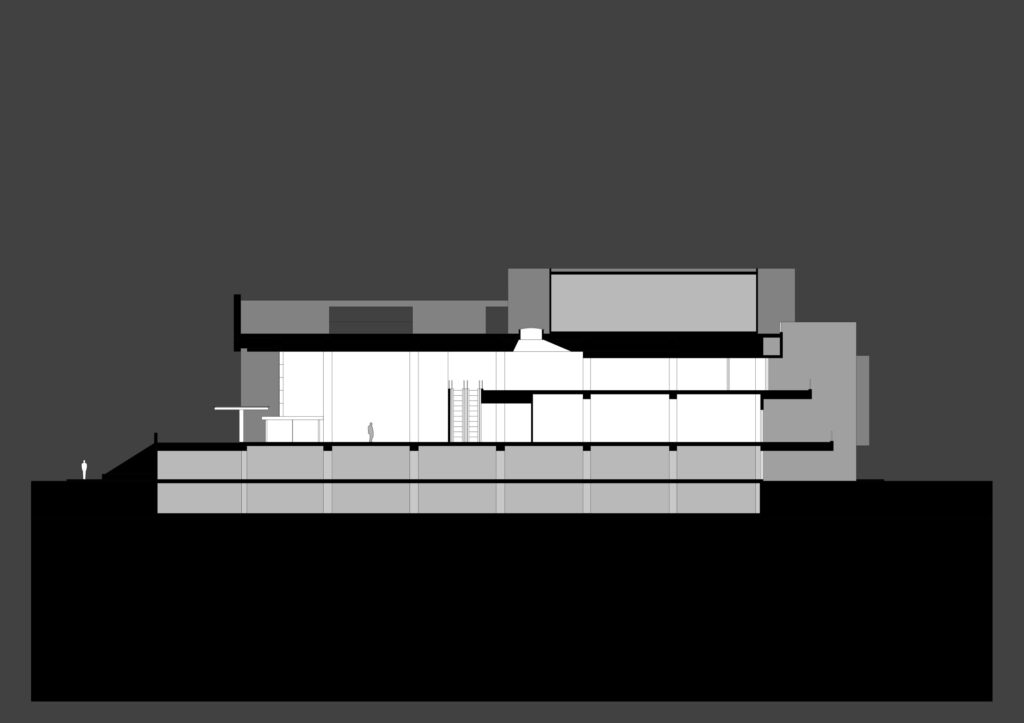

The design also focuses on natural elements to generate a peaceful environment. Despite the privilege of being an oceanfront site, the view of the water was unfortunately blocked by the building on the adjacent property. Instead of trying to make the building taller to accord water views, the architect “decided to bring the ocean inside the building.” The large waterbody within the courtyard with the rooms and corridors overlooking it was a conscious design device to this end. The sight of still water and the sound of water cascading from a concealed spout in the wall have a soothing effect on patients sitting in the space. The water level matches with the floor level and gently disappears into a fine slot within the flooring.

The reception lobby, the waiting areas, the cafeteria and research labs are placed around these water bodies. Considering Lisbon’s beautiful weather, outdoor space next to the water creates a beautiful environment for the patients and their relatives to sit. Similarly, the scientists can also step out of their labs intermittently and sit below a tree while taking a break. The shifting shadows of the pergola cast on the curved stone-clad wall create visual interest throughout the day, and these courtyards are also visible from the patient rooms placed one floor above.

Escalators and lifts take one up to second-level overlooking the main lobby. The operation rooms on this floor are circular in shape with glass on one side.

Being in a hospital can be daunting, both physically and emotionally. A patient’s emotional state can play an important role in their recovery. And the emotional state of the relatives who accompany these patients can also not be underestimated. This elegant building has given prime importance to these factors beyond fulfilling its functional requirements. Here, architecture will work together with medicine and research as agencies of hope and healing.

Project Details:

Name: Botton Champalimaud Pancreatic Cancer Centre

Location: Lisbon

Client: Champalimaud Foundation

Status: Completed (2022)

Area: 34,000 sqm

Architects: Sachin Agshikar, HDR, Joao Laranjo

Structural engineer: LNM

MEP consultants: Vanderweil

HVAC consultant: Lusoclima

Photographs: Dan Schwalm ©2023 HDR