We do not believe in ourselves until someone reveals that deep inside us something is valuable, worth listening to, worthy of our trust, sacred to our touch. Once we believe in ourselves we can risk curiosity, wonder, spontaneous delight or any experience that reveals the human spirit.

E.E.Cummings

Introduction from the book: Spirituality in Architectural Education

Our first and foremost task in life is to take hold of our spiritual destiny. ‘Spiritual destiny’ or ‘vocation’ are not words that are encountered often in educational circles. Nevertheless, we are beginning to see a concern in education that opens up the possibility of considering education as a spiritual venture.

Since 2008, the Walton Distinguished Critic in Design and Catholic Stewardship program, or “Walton Program,” has focused on the spiritual dimension of professing architecture. It proposes that architecture can and should assist the spiritual growth of humanity in the service of tackling both our urgent and enduring challenges. Its vehicle has been an advanced design studio strategically located between the physical and the metaphysical, culture and nature, life and intention, the worldly and the transcendental. This studio, called the “Walton Studio,” also anchors the Sacred Space and Cultural Studies graduate concentration — a unique curriculum inviting architecture students, faculty, and professionals to reflect, learn, research, and profess the deepest spiritual and cultural roots of the built environment. Offered every fall, the Walton Studio is intended for graduate students in the concentration and is usually available to senior undergraduates as an elective studio. The voluntary nature of taking this class is important because engaging spirituality demands willingness, maturity, and interest.

The other distinctive characteristic of the Walton Program is recruiting world-class architects to help envision and teach it. The Walton Critics, as the renowned guests are called, have come from the four corners of the earth — three from Europe: Alberto Campo Baeza, Juhani Pallasmaa, and Claudio Silvestrin; one from Asia: Prem Chandavarkar: one from South America: Eliana Bórmida; and six from North America: Michael J. Crosbie, Craig W. Hartman, Susan Jones, Rick Joy, Daniel Libeskind, and Antoine Predock. Over the past dozen years, their lectures, teaching, and interactions with students and faculty as well as the architectural community of the Washington- DC metro area have sparked renewed design, pedagogic, and scholarly interest in the unmeasurable dimension of architecture. The cumulative effect of these activities has enormously enriched not only our school but also the architectural discipline.

I am not saying this lightly. The high calibre and continuous commitment to spirituality of the Walton Program loom large in architecture, a field that has largely ignored it. The avoidance of spirituality is well documented by several architectural scholars and practitioners. Although this education remains resistant. How else do we explain the very few courses, publications, and discussions on the topic? I am here not speaking of teaching about religious buildings or designing sacred spaces. Rather, I am talking of curricula that address, facilitate, and/or develop spiritual sensibilities, worldviews, skills, and experiences through architecture. This is not something easy to do and may partially account for the lack of educational engagement. There are many challenges, starting with the belief that architectural education is a training ground for professional practice and therefore technically and secularly oriented. Yet, the humanistic and artistic roots of architecture extend well beyond the instrumental and therefore invite us to consider more significant dimensions of architecture, including spirituality.

A generation ago the influential “Boyer Report” recommended architectural schools steer their mission, curriculum, and service towards what could be fairly described as spiritual concerns. Similarly, another important document intended to guide future architectural education, this one by the International Union of Architects, was explicitly advising schools to incorporate spirituality into their professional programs. And these pointers have not been the only ones. Spirituality has been an area of increasing attention and study in higher education since the early 2000s. Nevertheless, as we will review in the next chapter, the interest of architectural education in spirituality remains inconsequential, at least officially. Perhaps this has to do with secular colleges and universities considering anything spiritual as defying the mandated separation between church and state. While these institutions allow some experimentation in the name of academic freedom, it is something else to institutionalize a spirituality-inclusive curriculum. However, examples of sustained attention to spirituality are also missing in faith-based schools of architecture, a fact that suggests a system-wide avoidance of the topic as earlier noted. But let us not dwell on negative criticism towards our existing educational model. Instead, let us observe what it is missing as an opportunity to make things better.

Let us include and appreciate traditional methods as the very source and energy from which we can spring forward. There is definitely much to learn, think about, and argue about the relationship between architectural education and spirituality. Unfortunately, as far as I know, no such focused study has been done before. There certainly are references to spirituality in pedagogy-centred papers or recorded teachings (most notoriously of Louis Kahn). But these examples (already few and far between) address spirituality indirectly, generally, or specifically to the topic at hand and stay clear of any consideration of its potential contribution (as a worldview, sensibility, skill, or experience) to architectural education. The absence of such larger educational, professional, and philosophical thinking explains by itself where we are today and demands addressing. For this reason, I will devote the entire next chapter to this task. Those readers that want to continue with this conversation are invited to leap forward.

Returning to the Walton Program, some questions may be raised about the role of famous architects in a studio advancing spirituality. Isn’t putting other human beings on a pedestal, particularly those enthroned by market capitalism and media societies, subversive to the very Walton enterprise? Critiques of the “star architect” system abound. A few responses may be advanced and, in the process, further illuminate the nature of this program. One answer has to do with the uncontestable quality of the architectural work and thinking these Walton Critics have gifted the world with and brought to the studio. Excellent role models do matter when we are trying to educate the next generation of professionals. Second, and while several of these eleven architects could be thought of as “star architects,” it is also true that they have provided ample evidence in their actions, writings, and buildings of a commitment to spirituality. In fact, they were selected precisely because of this.

But louder than any words is the fact that, however expensive it was for our school to bring them to campus, today’s financial reality made these architects lose substantial income by spending time with us and not at their offices. They were on campus teaching our students because they wanted to give back, to share, to educate. Anyone witnessing their dialogues with students during an ordinary desk crit or responding to their works during a public pin-up knows of their genuine devotion to teaching. Indeed, having closely worked with ten of the eleven Walton Critics myself, I can attest to each person’s authentic commitment to spiritual values in architecture and education. A fourth response refers to inspiration and validation. Having a highly recognized architect sitting, listening, and discussing their ideas side-by-side at their desk gives students an unmistakable message: they have something valuable to share with the world. American poet and playwriter E.E. Cummings makes this point beautifully:

We do not believe in ourselves until someone reveals that deep inside us something is valuable, worth listening to, worthy of our trust, sacred to our touch. Once we believe in ourselves we can risk curiosity, wonder, spontaneous delight or any experience that reveals the human spirit.

Who in youth hasn’t suffered the debilitating insecurity of realizing how little we know? Even if we feel that we have something to say, great doubt and anxiety remain. In many ways, we don’t believe in ourselves and are looking for external validation. This is an important job for the regular teacher to fulfil, no doubt. But if this confirmation comes from a world-class professional that the student admires, its impact is likely to be much greater. Besides, witnessing that such an individual is very much like them, a human being that breathes, has doubts, and makes jokes offers students invaluable, humanizing lessons. The power of these experiences is profound and, for some students, life-changing.

The last but no less important reason for bringing a recognized professional to campus has to do with the already mentioned lack of attention to spirituality in architectural education. Not only does the presence of respected figures confer immediate credibility to the effort but also each unique iteration builds a body of educational precedents in an area with hardly any. If we now add the longevity of the Walton Program and the quality of the work produced, we have enough evidence to claim (and for others to judge) the value of bringing spirituality into the teaching of architecture.

Mapping The Book

As advanced, the next chapter examines the role and relevancy of spirituality in architectural education. This section provides definitions, context, examples, and an overview of the main issues and questions surrounding the inclusion of spirituality in architectural education. Its substantial length is due to the complexity of the topic and the need to present appropriate arguments along with references and data when possible. Writing this chapter stretched my capacities as a teacher and scholar to the limit as I confess in the text. My hope is that, despite any shortcomings, the essay establishes a place where to begin discussing and advancing the spiritual dimensions of teaching and learning, practising, and experiencing architecture.

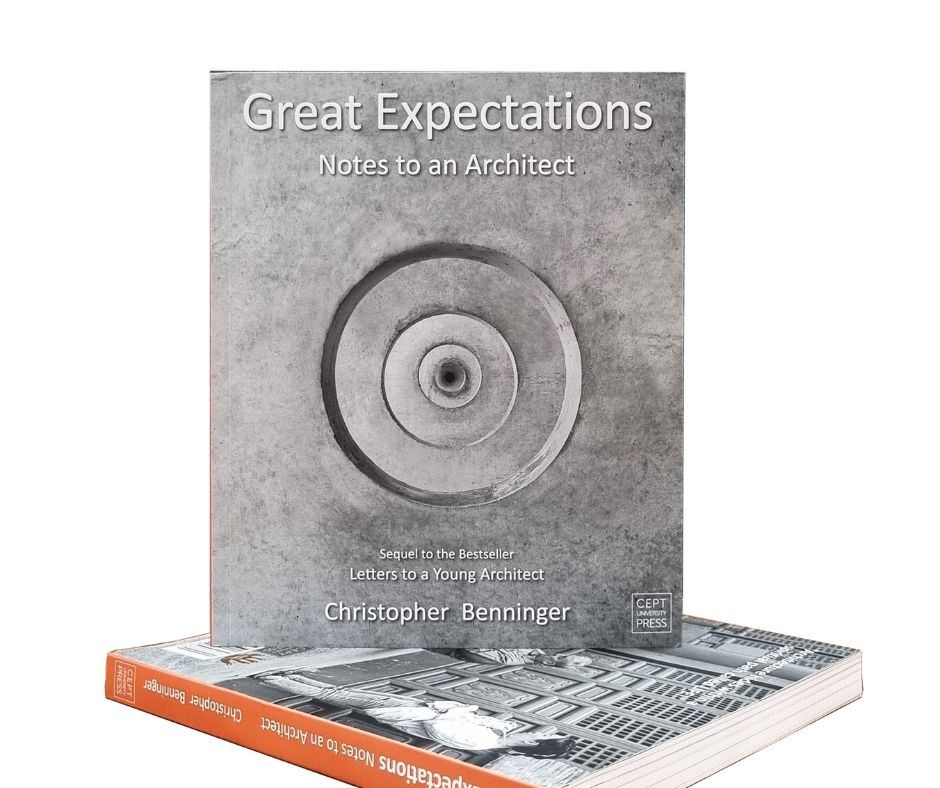

Chapter Three shares the fundamental organizational strategy, principles, curriculum, and pedagogy shaping all the Walton Studios. An overview of the warm-up and main assignments, the “big questions” posed, building programs utilized, “factoids,” and general outcomes are also included. Following this introduction, there are eleven sections that document the particular iterations of the studio. They go from the most recent effort in 2019 to the first one in 2009. The experiences are titled after their most defining characteristic, whether topical or pedagogical.

— 2019 Walton Studio with Daniel Libeskind. Being at the edge of order.

— 2018 Walton Studio with Susan Jones. Emotional and material foundations of architecture.

— 2017 Walton Studio with Rick Joy. Physical, existential, and spiritual home.

— 2016 Walton Studio with Prem Chandavarkar. Vocation and the deep self.

— 2015 Walton Studio with Michael J. Crosbie. Changing notions and practices of spirituality and the sacred.

— 2014 Walton Studio with Eliana Bórmida. Designing experiences: ritual, narrative, and embodiment.

— 2013 Walton Studio with Claudio Silvestrin. Contemplative and nonegotistical improvisation.

— 2012 Walton Studio with Alberto Campo Baeza. Building essential ideas.

— 2011 Walton Studio with Juhani Pallasmaa. The sacred task of architecture.

— 2010 Walton Studio with Craig W. Hartman. Consuming creation: rethinking consumption and materiality.

— 2009 Walton Studio with Antoine Predock. Intuiting spirituality through making, space, and light.

Each section starts with a summary of the studio’s intentions and characteristics, continues with three examples of students’ work, and finishes with an essay by (or interview with) its Walton Critic. In their writings, the architects reflect on the relationship between architecture and spirituality, sometimes relating it to the teaching experience. Given the rarity of such meditations in the disciplinary record, these essays are likely to become an important source of reference and guidance. The exception to this presentation format is the 2009 Walton Studio as I could neither retrieve most of the students’ work nor secure an essay from architect Antoine Predock, things that I apologize for. Next, I will briefly introduce the 10 essays in the order they appear in the book.

Daniel Libeskind is well known for his commitment to transcendent values and meaning. In his interview, he considers the relationship between architecture and spirituality from multiple, often provocative vanish points that expand our views and understanding. Libeskind acknowledges that “architecture is deeply spiritual” and that his work seeks to “go beyond what is given in the apparent reality of architecture.” His technique consists of designing buildings that invite our ordinary habits to drop off so that what lies beyond is revealed in all its sacred wonder. He advises us to make ample use of the arts and interdisciplinary to get in the right mindset for true cultural and architectural questioning. For at its very core, the 2019 Walton Critic convincingly tells us, “architecture is a quest. This is what makes it spiritual.”

He concludes by exhorting students to be (radically) themselves, take the path less travelled, and not believe what they hear or are told but ask for themselves.

Susan Jones reflects on how three underestimated sources of architectural ideation in the academy and profession – feelings, embodiment, and subjectivity—may be utilized to open up, explore, and respond to the spiritually charged topic of death and grief. She deployed these ideas in her 2018 Walton Studio utilizing a pedagogy of experiential emotivity, tectonic improvisation, and empathic design. Students accustomed to remaining at a safe distance from anything emotionally or spiritually compromising were drawn into a design-making process where body, feelings, and spirit were brought together in a dramatic process. This unleashed the transformative power of architecture to create spaces that connect us to the deepest plane of being.

Rick Joy writes like he does architecture: simply and meaningfully. The result is a short and to-the-point message: life is all about the spirit, whether we seek or find it within (soul, mind), without (nature), or with others (fellow human beings); and that each person may be naturally inclined to one or another of these paths. He makes no effort to hide which approach speaks to him, a sensibility that defines his buildings so well and which he eloquently spoke and taught about during his residency at UA in the Fall of 2017.

Prem Chandavarkar questions today’s architectural education grounded on modernity’s values of individualism, objectivity, and instrumentalism. Not only does such a system disable the student’s authentic engagement with others and the word but avoids or denies the sacred dimension of life. He proposes that teaching architecture ought to awaken each student’s vocation which is not self-bound but rather, as the root of the word “vocation” indicates, a call from a sacred source beyond ego that includes “the inner voice of others and the higher voices of the world.” The 2016 Walton Critic argues that since the student’s inner voice can be most easily recognized with the instructor’s assistance, a teacher-student-centered pedagogy should form the core of architectural education. Such a model of learning depends on the full interaction between both parties through an exercise of passion (to spark the inner voice and encourage its flourishing) and compassion (to balance the inevitable difficulties of doing so). In other words, bringing spiritual depth to architectural education “will require recasting the act of teaching, where it still valorizes knowledge, but is primarily an act of love.”

Michael J. Crosbie reflects on the intentions and pedagogy behind his 2015 Walton Studio: an open inquiry on the nature of sacred space today, a time when a majority of people (and youth in particular) describe themselves as “spiritual but not religious” or “nones.” What kinds of activities and building programs support our search for the transcendent today? Can there be sacred space without religious consecration or beliefs of some type? Is there sacred architecture beyond monasteries, temples, cemeteries, or memorials? Crosbie’s essay dives into the challenging, sometimes uncomfortable, but insightful questions surrounding the new, faith-unbound forms of spirituality in contemporary American culture. He invites us to consider that the “sense of the sacred is not static and unchanging and that every age needs to ask and try to answer what it is.”

Eliana Bórmida shares how her experiential approach to architecture was organically developed over two decades of designing buildings for the wine industry in Mendoza, Argentina. She points out that when we approach building programs phenomenologically, the fundamental relationships between nature, culture, and spirituality become synergized and opened to realization and enjoyment by all. The result is an architecture that invites beauty, identity, intimacy, meaning, embodiment, memory, emotions and transcendence, as those who have visited her buildings can attest. Bórmida finishes by sharing the design methodology her office uses to approach architectural commissions and that she taught in her 2014 Walton Studio with excellent results.

Claudio Silvestrin states that designing sacred space is the highest calling of architecture, one that demands architects to be “humble and put aside our school teaching, our degrees, our professional habits, and our self-referential ego to start afresh with a new mind.” This translates into thinking with our hearts and exercising careful spiritual discernment. Only then will we “design and build a bridge between Earth and Heaven, divinities and mortals and at the same time, make ourselves feel like we can be both citizens of the material world and the spiritual world.” The fact that Silvestrin used improvisation to ground the design of buildings normally considered not sacred in his Walton Studio has two far-reaching implications: (1) intuition, if properly applied, leads to the best architectural outcomes and (2) the “sacred” domain may extend into the secular realm if a building’s activities have spirituality at heart. These two inferences align with much of the 2013 Walton Critic’s writings and work.

The first and short text of Alberto Campo Baeza may seem a bit informal. However, it is when this writing is paired with his second piece “On Surrender and Universality” that this architect’s mind and approach come to light. Let me explain. Campo Baeza approaches the world emphatically, assuming the goodness of his fellow human beings and acting likewise. He puts himself in the other individual’s shoes and tries to connect at a personal level. If we read his second essay with this attitude at heart, we will understand that his passionate argument for a universality grounded on selfless style and simplicity is not advocating for cold, detached, stoic, or puritan architecture. Rather, he is telling us that beauty, the radiance of being, shines forth when we stop embellishing or adding to things and remove ego from the equation. Campo Baeza invites us to join him and his five inspiring “friends” (T.S. Eliott, Orgega y Gasset, and Alejandro de la Sota along with Grombrich and Melnikov) in letting go of provincialism, individualism, and noise to find our true, spiritual home.

In “The Art of Teaching”, Juhani Pallasmaa offers ways to move beyond today’s limited, and limiting model of architectural education. His diagnosis is compelling. Architectural education focuses too much on “externals” and little, if at all, on the inner reality of the students. Yet, “the very essence of learning in any creative field is embedded more in the student’s sense of self and his/her unconsciously internalized image of the world than in detached and external facts.” Addressing the situation, the 2011 Walton Critic tells us, demands to recognize and restore the central but often ignored role that emotions, embodiment, poetics, experience, existential meaning, authenticity, the unconscious, and empathy play in the dialogic act of teaching and learning architecture. These insights agree with ongoing discussions in higher education about how to integrate the spiritual dimension of humanity in the cognicentric, instrumental, and impersonal pedagogy and curricula of most universities. In this context, Pallasmaa explains the importance of teachers in the learning process (reminding us of Chandavarkar’s essay), what characteristics they should personify, and how to measure their success. He concludes by sharing examples of such “art of teaching” in the design studio. It would be hard to find another writing that so succinctly offers so many insights and directions on how to improve today’s architectural education.

Craig W. Hartman considers the great challenges of our age and proposes an architecture that honours nature and assists human flourishing “through principles both ancient and contemporary.” This means acting sustainably, responding to local places and history, and seeking beauty without giving up the positive gains of the 21st Century. He invites architects to use “space, form and the poetics of light to create a modern humanism that serves the culturally diverse” communities of today. Hartman then conducts a comparative analysis of five outstanding modern churches (Le Corbusier’s Chapel of Ronchamp in France, Eladio Dieste’s Church of Christ the Worker in Uruguay, E. Fay Jones’ Thorn-crown Chapel in Arkansas, Peter Zumthor’s Bruder Klaus Field Chapel in Germany, and his own Christ the Light Cathedral in Oakland, California). This study reveals a variety of ways in which our immanent and transcendent natures may be mediated through sacred architecture. The 2010 Walton Critic concludes his essay by inviting both the academy and the profession to use architecture to bring spirituality to our global urban civilization.

The book closes with the round-table discussion that launched a four-day-long event that celebrated the 10th anniversary of the Walton program in October 2018. Moderated by Michael J. Crosbie, he and another five Walton Critics —Juhani Pallasmaa, Alberto Campo Baeza, Eliana Bórmida, Prem Chandavarkar, and Susan Jones —shared their meditations on “Spirituality and Architectural Education and Practice” I will never forget that night. The level of attention in the audience was only matched by their silence. As each Walton Critic added their heartfelt reflections to the one before, the atmosphere in the room became increasingly charged with more clarity, depth, gratitude and spirit. In my thirty-five years in academia, I had never witnessed more compassionate, direct, and authentic teaching. I was not the only one with tears in my eyes as many colleagues and students confessed to me later. This transcript cannot fully account for what happened that memorable evening but it does capture the words elicited. In them, the reader will find many insights, ideas, references, and recommendations to take home and put to good use. An Appendix with testimonials from Walton Program alumni and three short essays I wrote completes this volume. Since I regularly employed my texts in the Walton Studios, it is appropriate to include them in this volume. They also provide another vanishing point to the discussion about spirituality in architecture. The first one is the “Voluntary Architectural Simplicity VAS) Manifesto.” Originally written in 2003 and improved throughout the years, it proposes an ethical-aesthetic way to respond architecturally (and spiritually) to the challenge of our time. The second paper is “Choosing Being,” a critical reflection on today’s cultural hallucination of having and doing. The argument calls for refocusing our personal and social efforts on developing being to bring spirituality and balance back to our lives and world. Last is “On the Architectural Design Parti,” my most popular writing based on web views (nearly 24,000 in early August 2020, counting its English and Spanish versions posted on Academia.edu). This short piece is a meditation on the nature and function of the design “parti” that seeks to illuminate the subject without undermining its true magic if not mystical quality.

Parting Words

Spirituality is behind the best examples of architecture across space and time. In fact, it may well be what originated it — if we understand architecture to be more than physical shelter. The archaeological evidence of Göbekli Tepe in Southeastern Turkey, a temple built for the worship needs of large numbers of prehistoric people, strongly supports this possibility. Built 6,000 years before Stonehenge and the Giza Pyramids, more time had passed between when those ancient structures were built and Göbekli Tepe than between them and us! 4 And ever since, the most accomplished works of architecture, regardless of place or culture (at least until late 19th Century), have been overwhelmingly associated with spiritual drives. This is a fact that architecture educators and practitioners readily accept. Yet their consent doesn’t translate into an openness to spiritual engagement. The reason may have to do with the way they approach those masterpieces: dispassionately, analytically, like someone who has never swam a lap commenting on the swimming performance of an Olympic champion on TV. Such a third-person perspective is unable to grasp that those great works of architecture are amazing because the people that conceived and built them were living the spirituality they were expressing. Simply put, historical, scientific, typological, or any such removed analysis will not get us to attain (or understand) the extraordinary results of old as much as experiencing a similar spiritual mindset. Swimming and competing (not necessarily winning) will enable us to understand and say something meaningful about the Olympic swimmer.

But who wants or needs to engage architecture or spirituality in such a personal way in our secular age Perhaps we do. If we looked at many of today’s best buildings with an open mind, we would discover that at least some of them have been shaped by visions or sensibilities that are certainly spiritual —whether the architect of record realized (or acknowledged) it or not. Design, knowledge, technology, skills, labour, materials, finance, management, and the rest are all fundamental. Still, it is what brings them together with love, commitment, and vision that makes greatness possible. Without spirit, the type of effort required to attain such excellence succumbs. It takes something extraordinary within to accomplish something extraordinary without it. We know this to be true in our bones but, somehow, we need to keep reminding ourselves, don’t we? And, if we sense this to be true, if we think, feel, or know that spirituality is at work in our best architecture (even today’s), shouldn’t we reexamine our discipline’s attitude towards it?

For 12 years the Walton Program has been working with the conviction that spirituality is an important part of learning how to profess architecture. Because of its novel and untested nature, this effort started as and continues to be an ongoing experiment in architectural education. For this reason, traditional metrics may not be the best way to evaluate its success — for experiments may fail. Perhaps, the authenticity of the effort and what it teaches us should be used instead. By documenting eleven experimental trials and as many reflections, this book seeks to raise awareness, spark discussion, and offer a precedent of the role that spirituality can play in training future architects and, transitively, practice. May this work be a contribution, however small, to a world in dire need of spiritual sensibility.

Spirituality in the Design Studio, Introducing the Walton Program

- Edmund O’Sullivan, “Emancipatory Hope,” in Holistic Learning and Spirituality in Education, eds. By John P. Miller, Selia Karsten, Diana Denton, Deborah Orr, and Isabella Colalillo Kates (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2005), 69-78, citation in p.70.

- The biases against addressing spirituality in the architectural academy and profession are discussed by Michael Crosbie, “The Sacred Becomes Profane,” in Architecture, Culture, and Spirituality, eds. Thomas Barrie, Julio Bermudez, and Phillip Tabb (New York: Routledge, 2015), 59-69; Michael enedikt, God, Creativity and Evolution. The Argument from Design(ers) (Austin, TX: The Center for American Architecture and Design, 2008); Julio Bermudez, “The Extraordinary in Architecture,” 2A 12 (2009): 46-49; Karla Britton, Constructing the Ineffable (New Haven, CT: Yale School of Architecture, 2011); and Renata Hejduk and Jim Williamson, “Introduction: The Apocryphal Project of Modern and Contemporary Architecture,” in The Religious Imagination in Modern and Contemporary Architecture. A Reader, eds. R. Hejduk and J. Williamson (New York: Routledge, 011),1-9.

- “Higher education has given ample proof of its viability over the centuries and of its ability to change and to induce change and progress in society. Owing to the scope and pace of change, society has become increasingly knowledge-based so that higher learning and research now act as essential components of the cultural, socioeconomic and environmentally sustainable development of individuals, communities and nations. Higher education itself is confronted therefore with formidable challenges and must proceed to the most radical change and renewal it has ever been required to undertake, so that our society, which is currently undergoing a profound crisis of values, can transcend mere economic considerations and incorporate deeper dimensions of morality and spirituality.” (emphasis added). UIA Architectural Education Commission, UIA and Architectural Education. Reflections and Recommendations (Paris, France: International Union of Architects —UIA, 2002), URL http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?-doi=10.1.1.549.4828&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed July 9, 2020). The UIA document is actually quoting a paragraph from the preamble of UNESCO, Higher Education in the Twenty-first Century: Vision and Action, v. 1: Final Report (Paris, France: UNESCO, 1999), 20. URL: https://unesdoc.

unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000116345 (accessed July 9, 2020). - “Göbekli Tepe” in UNESCO World Heritage. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1572/ . See also Andrew

Curry, “Gobekli Tepe: The World’s First Temple?” Smithsonian Magazine (Nov 2008). URL: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/gobekli-tepe-the-worlds-first-temple-83613665/ (accessed July 13, 2020). Charles C. Mann, “The Birth of Religion,” National Geographic 219, no.6 (June 2011): 34-59.

Spirituality in Architectural Education, Meditations

- Parker J. Palmer and Arthur Zajonc with Megan Scribner, The Heart of Higher Education. A call to Renewal (San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass, 2010), 49.

- See chapter 17 “Learned Ignorance” in Edward Harrison, Masks of the Universe (New York: McMillan, 1985), 273-278. Harrison’s piece is based on “De Docta Ignorantia” by philosopher/theologian Nicholas of Cusa (1440). From a “learned ignorance” perspective, “the more we know, the more aware we become of what we do not know” (Harrison, p.273). Learning thus becomes a process of coming to know and humbly accepting our ignorance.

- Searches of articles relevant to architectural or design education using keywords such as “spirituality,” “spirituality and education,” and “spirituality and architectural