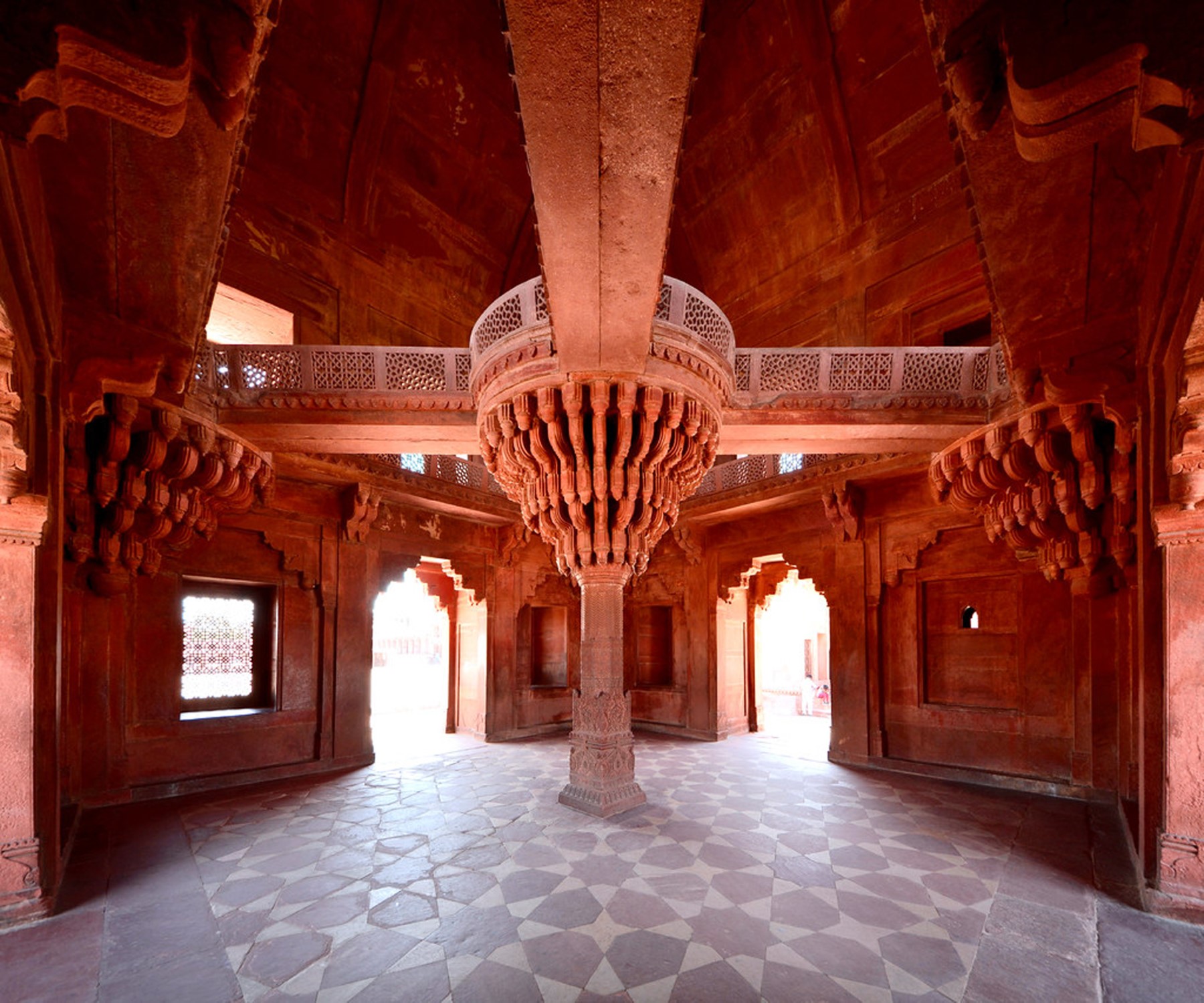

The terms Urbanisation and urbanism are often confused with one another because the urbanization pattern of a country is indeed determined to a large extent by the sociocultural and environmental situation besides the economic and the political and demographic decisions of the government of the time- parameters that also affect urbanism to a great extent.

Let us examine the status of these parameters post-75 years of Independence.

Urbanisation refers to the shift of the population from the primary to secondary and tertiary sectors, accompanied by the relocation of the population from ‘rural’ to ‘urban’ areas.

Urbanism, on the other hand, is a term that conveys the character, organization and quality of urban life in cities.

This essay on urbanism is not meant to tangle the reader in a web of statistics, so we shall steer clear of statistics/figures unless it becomes unavoidable.

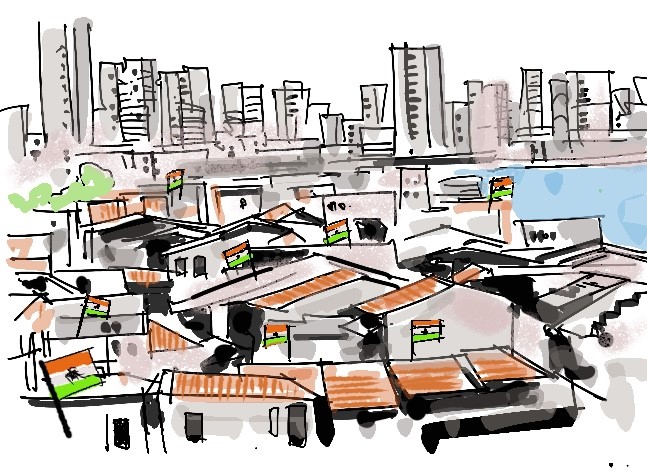

Urbanisation in India has quite a few unique characteristics. Urbanisation in India has quite a few unique characteristics. The rate of urbanization in India is lower than that of many other countries, including the world average- the urban population (as per the 2021 census ) of India is 35.39%. This definition of ‘urban’ in India excludes a huge population purely for administrative reasons. Besides ‘urban’ areas (as defined by the census of India), there are what are referred to by different, confusing and quite overlapping names such as census towns, statuary towns, urban agglomerations, city outgrowth, and multicity agglomeration. These are all Avatars of ‘urban’ settlements with some minor additional alterations in the technical definition. But, all have a definitive ‘urban’ character in spirit and feeling. Large or small, official or unofficial, planned or organic- these are all ‘urban areas’.

This is quite like the Gods in Indian mythology- thousands of them are known by hundreds of different names; nevertheless are all God in the end.

So, in this sense, trying to study Indian urbanism in terms of demographic statistics of the census alone is a very inapt way to understand this already complex phenomenon.

Urbanisation in India has been rapid and uneven. Between the decades 1951 to 2011, Delhi has seen a jump in its population by 6.7 times. This is reflected throughout India at a sliding scale in most of the metros. Needless to state, these are accompanied by the other Avatars of urban growth. Built-up cities- spatial conditions are largely the outcome of environmental and planning policies and dictates of the government.

City living is a great leveller. Urbanism is supposed to broaden one’s perspective on life in general.

The sad reality, however, remains that age-old issues (non-issues), like caste and religion, still rule our thinking. Stratifying the whole country’s population by caste and religion remains a priority on the political agenda of many parties.

Environment, social equity, and social justice are relegated to the background for very remunerative decisions such as high-end housing, using the incidents of atrocities on women to create TV debates, making a big show of a new road or highway without the mention of the hundreds of trees removed, and has become quite an acceptable norm. So have caste, religion-based segregation and overlooking issues of gender equity. These deep-rooted prejudices and biases, aided by a small dose of ‘patriotism’, come in very handy for political manoeuvring- to divert the attention from the REAL issues.

Thus there exists a correlation between urbanization and urbanism- in the larger context, one feeds off the other. While one segment of the population inches upwards on the economic ladder ( the big fat Indian middle class), generating a greater demand on limited resources like land, water, fuel, electricity and affordable housing, an equally big part of the population, unsupported by a sympathetic economy, slides into informality and poverty. This scenario not only takes a heavy toll on environmental factors but makes the inequity factor more prominent- one is left to fend for oneself to seek social or civil justice.

As city planning objectives get bigger and more grandiose, the common man gets more marginalized.

Kavas Kapadia

The universal reach of information technology has hastened the process of global unification of urban order and disorder. Westernisation is mistakenly but generally substituted for modernization, fueling king-size aspirations of citizens, especially the emerging middle class. Urban areas represent the denser agglomeration of the population, so it becomes imperative for all stakeholders to be more sharing in dealing with their fellow citizens. But, urbanization triggers off just the opposite reaction of Individualism (self-centeredness). This common trait is most notable in the urban population, followed by the liberation offered by urban impersonality and anonymity.

It is a well-established fact that in India, the formal sector is unable to absorb the onslaught of in-migration into the cities. The construction, low-order manufacturing and self-employed informal sector absorb these migrants. They stay in substandard housing; slums and unauthorized settlements present the other side of the picture of the minor affluent population segregated by gated communities. Just how fragile and susceptible the lives of the urban poor were witnessed when the first COVID lockdown, which caught all the migrant labour by surprise, was announced. On the other hand, you have to visit an airport or one of the several upmarket malls or the sales of luxury vehicles to appreciate the spending capacity of a small minority of the population.

Excessive opulence displayed amidst poverty ferments palpable inequity.

Kavas Kapadia

This situation creates an intriguing duality, conflicting but very Indian- the urbanism of the poor and the urbanism of the rich. It is not difficult to imagine how each category interprets urbanism.

So what keeps India going on in the face of such adversity?

Hope.

People throng to the city because it provides the hope of employment and a better quality of life than what they leave behind and an unfailing faith in the numerous Gods and Goddesses whose term, unlike that of the political party in power, never runs out.