One of the things that the coronavirus lockdown is teaching us, is to deal with our fear of confinement, or in other words claustrophobia. Our societal fear of being trapped and restrained in one place goes against the grain of our cultural existence.

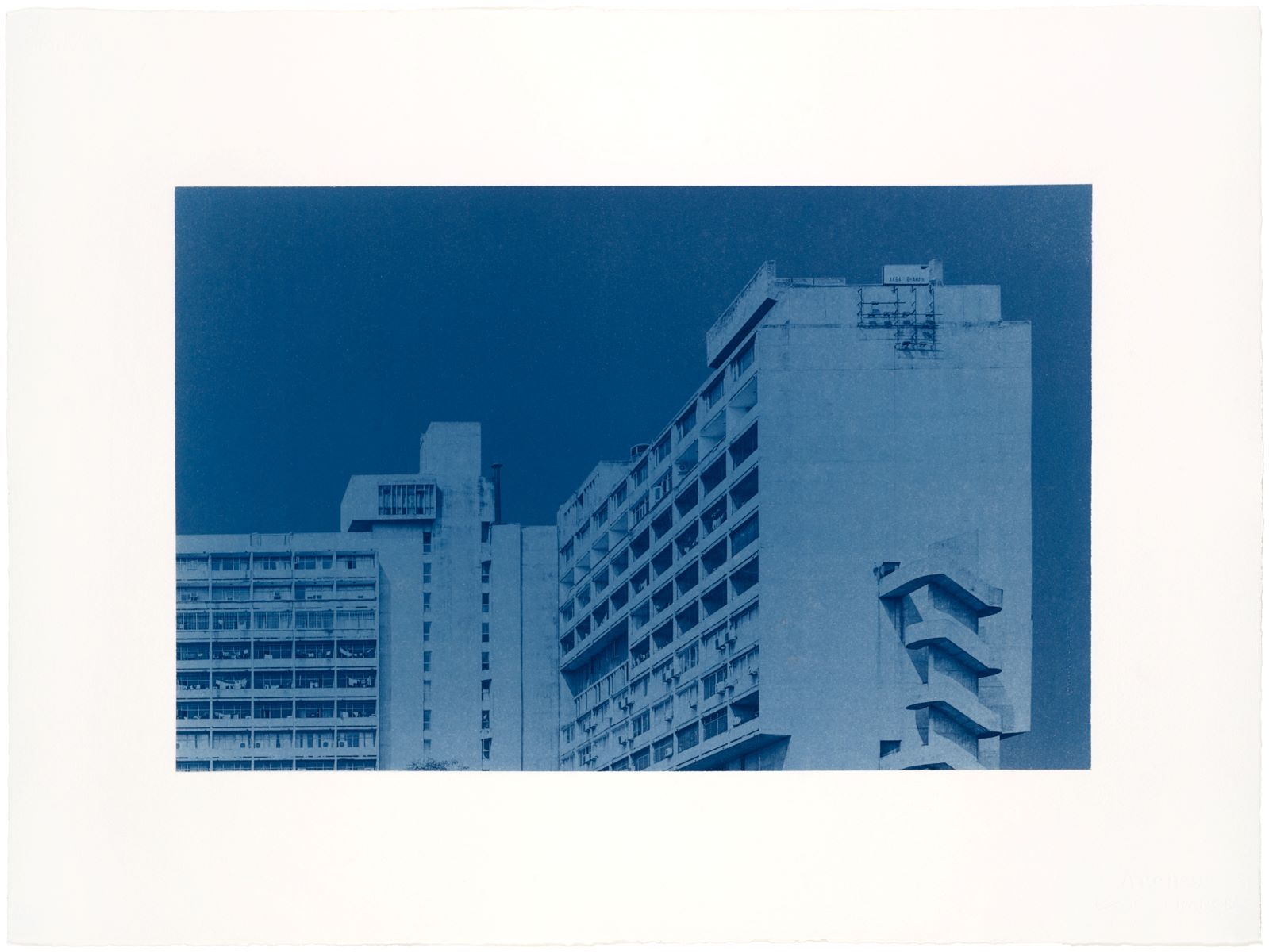

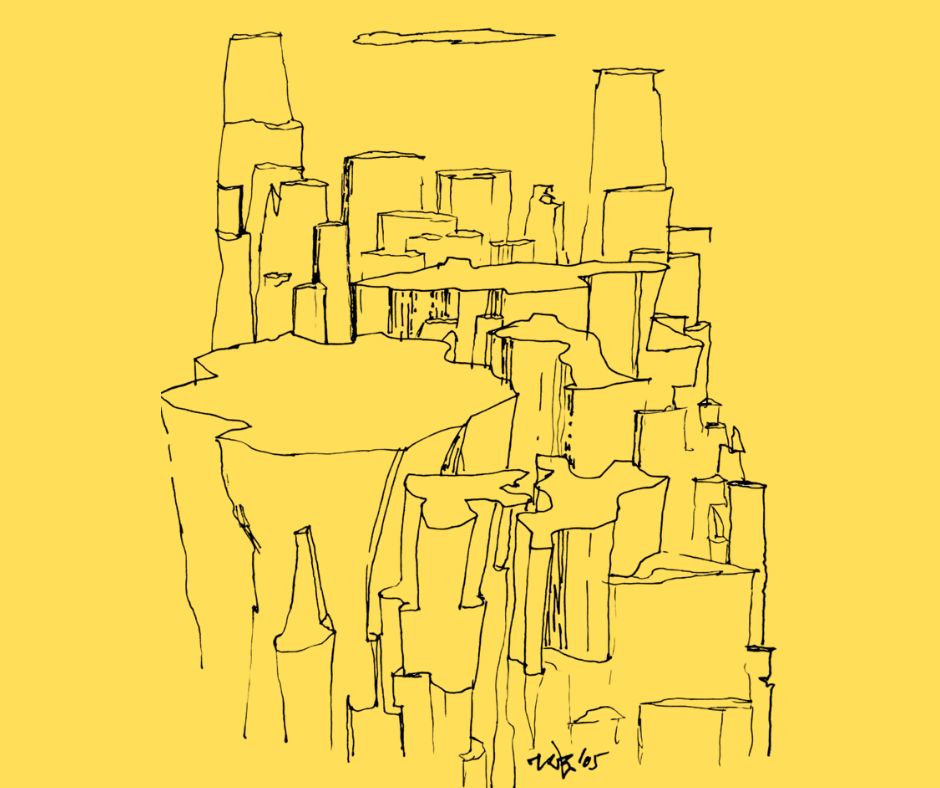

At the beginning of the lockdown, the experience of living and working in our own homes was one of tranquillity and rest. It started off as comforting, but it slowly turned into a frightening one. Our world seemed to be narrowing down, like as if we’re travelling through a tunnel in which the walls are closing in together like a funnel. With being locked up in our own homes, we have not only lost our freedom, we have also lost the city as our living room. Our lives never merely played out in the premises of our own homes and offices. The parks and boulevards of our cities were our backyards, and the restaurants of the city our dining rooms.

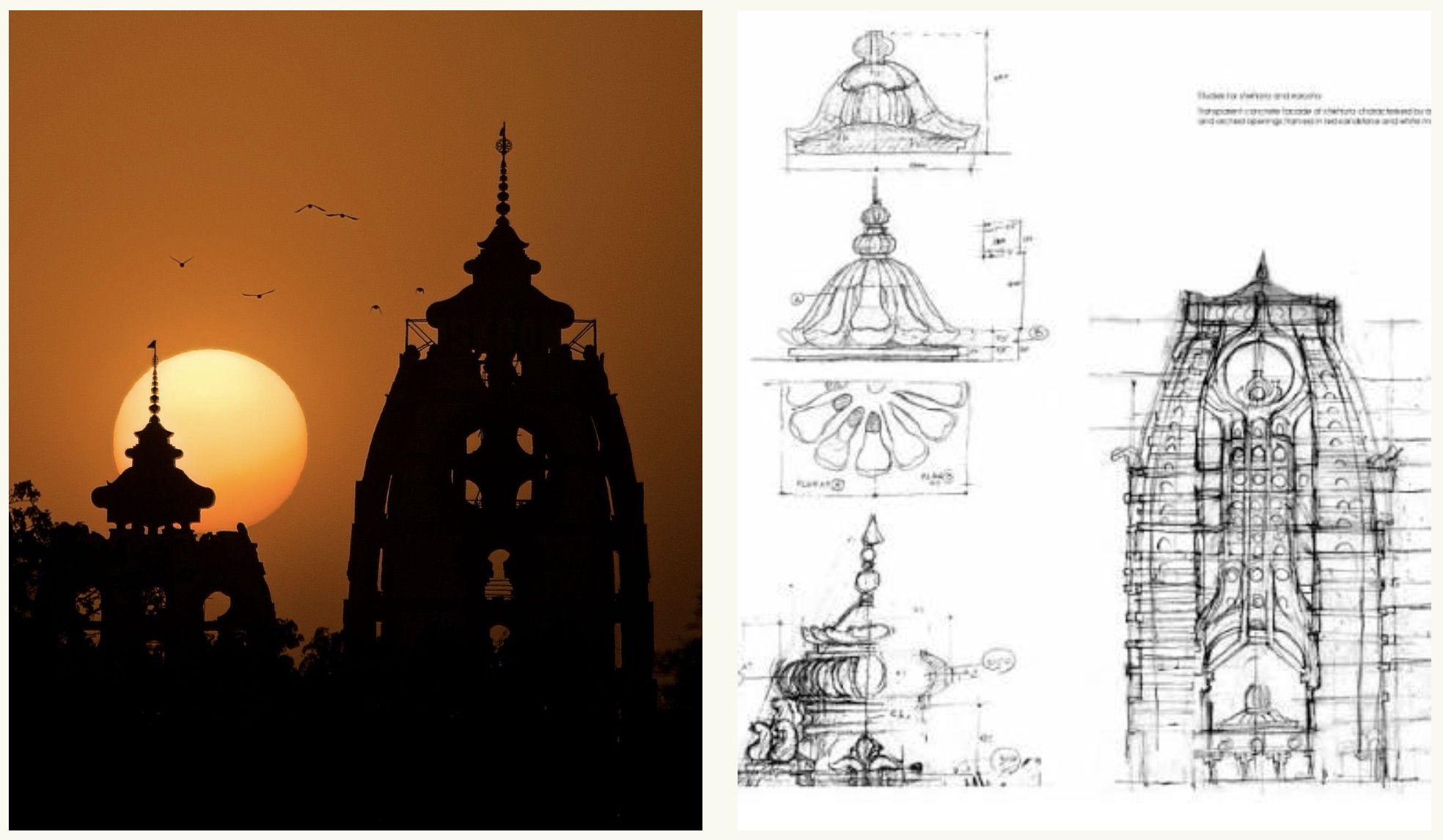

Up to now, we all believed in the idea of expanding our scope, our horizon, living in ever-larger places, travelling more frequently, and to more remote places. The airline industry expanded exponentially throughout our lifetime, and the tourism industry started dominating the economy of entire countries. We have been raised with the cultural belief that travel is an essential right. Even more, we believe that it is an undeniable prerequisite for us to be relevant. The fact that our lives have turned digital, has reinforced our notion that our lives only matter through the experiences and adventures that we gather along the way.– Robert Verrijt,

Architecture BRIO

Business travel has become an excuse that nourishes our cultural addiction to travelling. However while business travel has surged, the real need to travel for work has dwindled. Especially in the last 5 to 10 years, the explosion of bandwidth had already completely transformed our workflow and had already enabled us to practice #WFH.

However, we habitually believe travelling is a fundamental opening to the world, a source of freedom and of learning. Ironically this very urge to travel has amplified the coronavirus crisis. It has inevitably led us to where we are now: at home. For those of us living in urban India, it means we’re probably confined to a small apartment. Most of us will probably have to make do without even a balcony to step out into.

This leads one to question, how large a place one should live in to lead a happy life? The short story by Tolstoy of 1886 “How Much Land Does a Man Need?”, starts with the protagonist Pahom believing that each time he acquires more land, he becomes happier. Instead, with each purchase of more land, he wants more. Eventually, this leads to his death, when he collapses of exhaustion attempting to traverse all of his lands in one day.

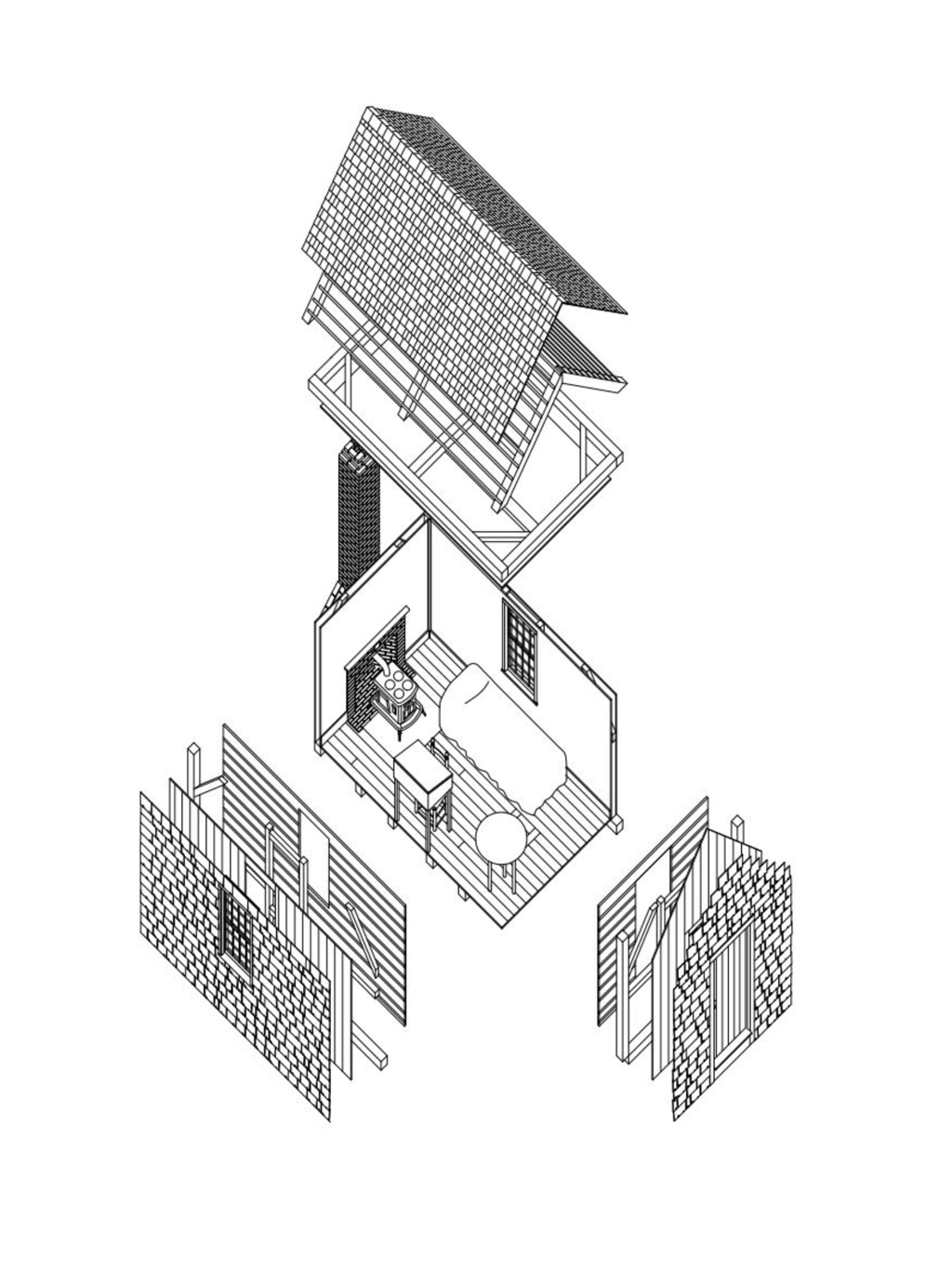

Henry David Thoreau seemed to have asked a different question when he escaped the perils of the industrialising world to build a cabin at Walden Pond in 1845: What is the smallest house I could live in? Hoping to align with the wisdom of nature and immersing himself in the landscape, his single room house measured only 10’ by 15’. He aimed to live a more sustainable life, as illustrated by another question he asked himself: “What’s the use of a house if you haven’t got a tolerable planet to put it in?”1

So what will happen when the lockdown is lifted? After squeezing through the tunnel, will we live like never before, and live life to its fullest? Or have we finally realised that our world is not able to afford our lifestyles any longer. Human activity has changed the world in such a way that soon we will not be able to recognise it. In order to reverse or mitigate the effects of the Anthropocene, we will have to lead different lives. This realisation that as a consequence, we will have to travel less, has an even more claustrophobic effect on our psyches. The idea that we should stop travelling to prevent the arctic ice from melting is terrifying. It narrows down our experience of the world we live in. It triggers a claustrophobic feeling of being trapped in our immediate surrounding, even more than the momentary entrapment that we are enduring right now.

1. Thoraeau, Henry David. Familiar letters of Henry David Thoreau p.416