Abstract

The project explores the socio-spatial condition faced by people in transit through the lens of the selected site “Parco Roya” located in Ventimiglia, Italy. The socio-economic histories of this site have been acknowledged as this post-industrial infrastructure at one point embodied a space of transboundary trade, and economic and cultural vitality within Ventimiglia. The aim and objective of the project is to speculate on ways people in transit may reclaim, reimagine and subvert one’s living space through engaging in materiality. The research observes the architectures of displacement and confronts the condition of displacement by observing the inhabitation of post-industrial infrastructures as spaces of refuge or reception.

In recent years, the Parco Roya site has become a symbol of the broader challenges and complexities surrounding migration in Europe as the number of refugees and migrants seeking asylum continues to grow. Originally established as a Red Cross Camp for migrants entering Ventimiglia, the site has since been left uncertain, caught between the possibility of commercialisation or conversion into a reception centre for people on the move.

The conception of home derives from the interplay between contradictory forces: mobility and stasis. The navigation of these dynamics within the context of social, political and cultural realities allows individuals to aspire to a sense of home. The process consists of a set of interventions that affords a realm of possibilities for reception and homemaking techniques for people in transit. Within a state of cyclical hostility and oppression, the selected modes of intervention afford a sense of optimism for people in transit at Parco Roya.

Through the act of reclamation and re-appropriation of spaces to provide for one’s needs, people in transit gain the ability to interrogate existing power structures and reshape an authority that one may face. The affordance of agency over one’s space allows for a quality of empowerment, through the assertion of one’s rights and identities. Beginning an inquiry into the dialectic relationship between mobility, stasis, and authority by interrogating the symbolic and physical manifestations of post-industrial infrastructures. How may one mobilise various possibilities of reception and home through a practice of subversion? Engaging with the materiality of a post-industrial infrastructure acts as an entry point into the selected site.

Keywords: Settlement, Transboundary, Informal, Solidarity

1. The Politics of Migration

- Closure of the French Border

In 2015, owing to the terrorist attack in Paris, the French government declared a state of emergency and ensured the closure of the Franco-Italian border. As per the Schengen Agreement, countries are only supposed to suspend the agreement’s implementation in exceptional circumstances, but France has done so repeatedly in 2015, 2016 and 2019 respectively.

Initially, internal border controls were scheduled to be in effect until the end of April 2020, citing reasons such as the “persistent terrorist threat,” an upcoming significant political event in Paris, and concerns about “secondary movements” of people. However, it is essential to note that the last reason, which views the presence of migrants as a threat to public order or security, contradicts the principles of the Schengen Agreement. The Schengen Agreement does not categorise the mere presence of migrants as a threat to public order or security. In 2017, the French government resorted to using drones and deploying dogs to conduct searches in vehicles for migrants. These measures highlight the heightened security measures taken by the authorities to control migration in the region during that time. Such actions have been subject to criticism, as they may infringe upon the rights of individuals and raise concerns about the treatment of migrants. Due to this, a large number of people in transit generally termed ‘illegal migrants’ (by the states of the EU) who paved their way from their home countries got stranded in the border town of Ventimiglia. The closure of the border further adds the militarisation by the border police force to the militarisation and hostile morphology of the mountains.

Sandro Mezzadra & Brett Neilson in their book ‘Border as a Method’ (p. 05) write ‘no political border is ever the mere boundary between two states, but is always sanctioned, reduplicated and relativized by other geopolitical divisions.’ Basically, borders are symbolic demarcations represented by lines on maps, whether they exist on land, at sea, or between land and sea.

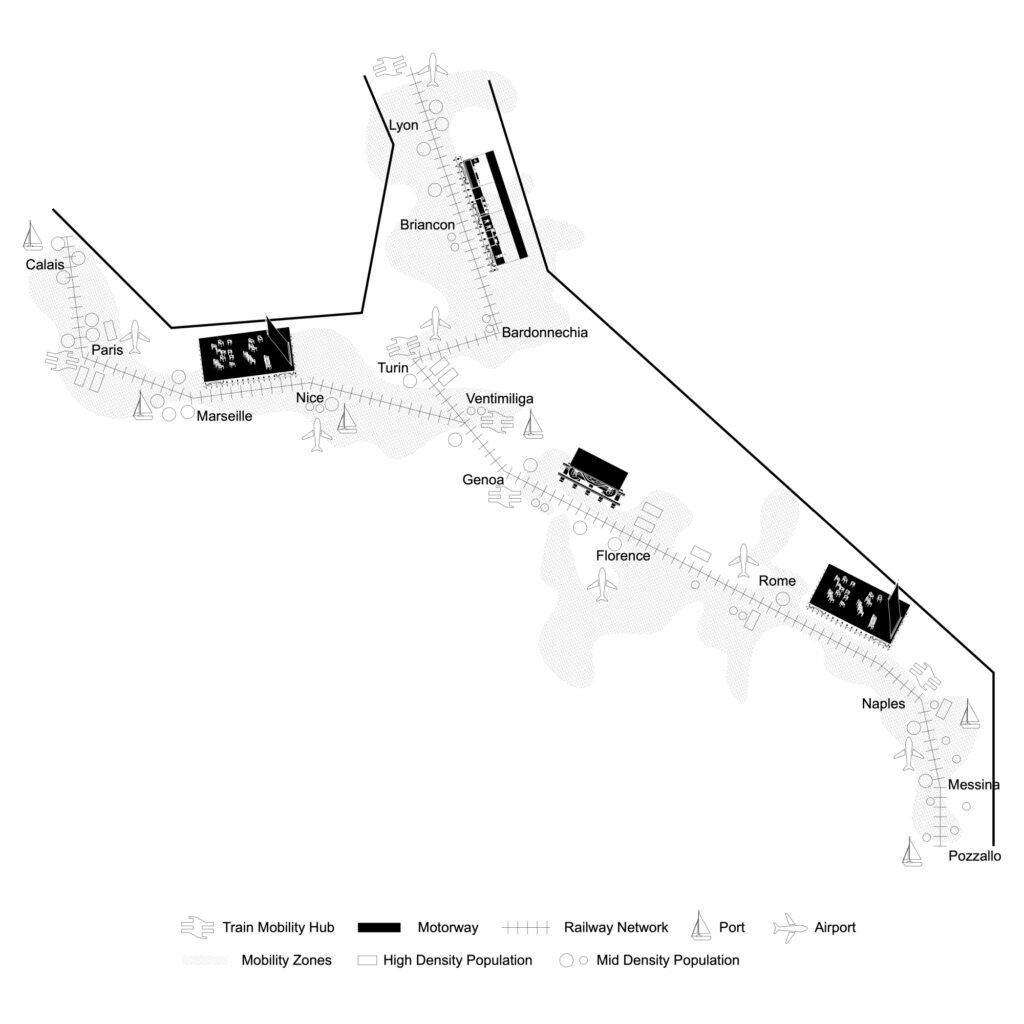

b. Ventimiglia as a bottleneck

Ventimiglia is a border town on the northern coast of Italy located on the Roya River approximately 12 km away from the French border. The town is close to important Ligurian tourist resorts including Bordighera (6 km), and Sanremo (16 km), while it is 30 km from the Principality of Monaco and 40 km from Nice” (Ventimiglia (IM). Ventimiglia is a border town on the northern coast of Italy located on the Roya River approximately 12 km away from the French border. The town is close to important Ligurian tourist resorts including Bordighera (6 km), and Sanremo (16 km), while it is 30 km from the Principality of Monaco and 40 km from Nice” (Ventimiglia (IM). The geographic location of Ventimiglia places the town within a strategic position as it exists as the final railway station before entering the French Border, along with convenient transport networks that connect Ventimiglia and Nice.

In August 2015, Ventimiglia attracted media attention when protests erupted, and authorities dismantled the informal camp located at Balzi Rossi. The incident brought widespread public awareness to the situation, shedding light on the issues faced by migrants in the area. The events surrounding the camp’s removal sparked discussions and debates about the treatment of refugees and the urgent need for better solutions to address their living conditions and rights. As aforementioned, Ventimiglia’s proximity to the French border fosters a high influx of migrants who aim to cross the border in the hope of seeking asylum. However, due to continuous border closures enforced by legal authorities, migrants face extreme pushback, consequently producing a condition described as a “bottleneck” within Ventimiglia, Italy.

The Place image, defined as ‘an image that the people carry in their mind about an appearance of a place’, was developed by the urbanist Kevin Lynch in his book The Image of The City (2008) to describe the relationship of the city to temporary spaces and the rituals that take place within or makes use of them. Lynch explains Place Image (p.119) ‘Where physical homogeneity coincides with use and status, the effect is unmistakable.’ He describes this by giving an example of how Beacon Hill is directly reinforced by its status as an upper-class residence, unlike the usual American case. The use-character receives little support from the visual-character. A city will not exhibit a stratified order but will be a complicated pattern, continuous and whole, yet intricate and mobile pattern.

In the case of Ventimiglia, even with all the documents/papers in place, the people in transit have little chance of being granted asylum elsewhere due to the Dublin regulation. Therefore attempted border crossings are rampant.

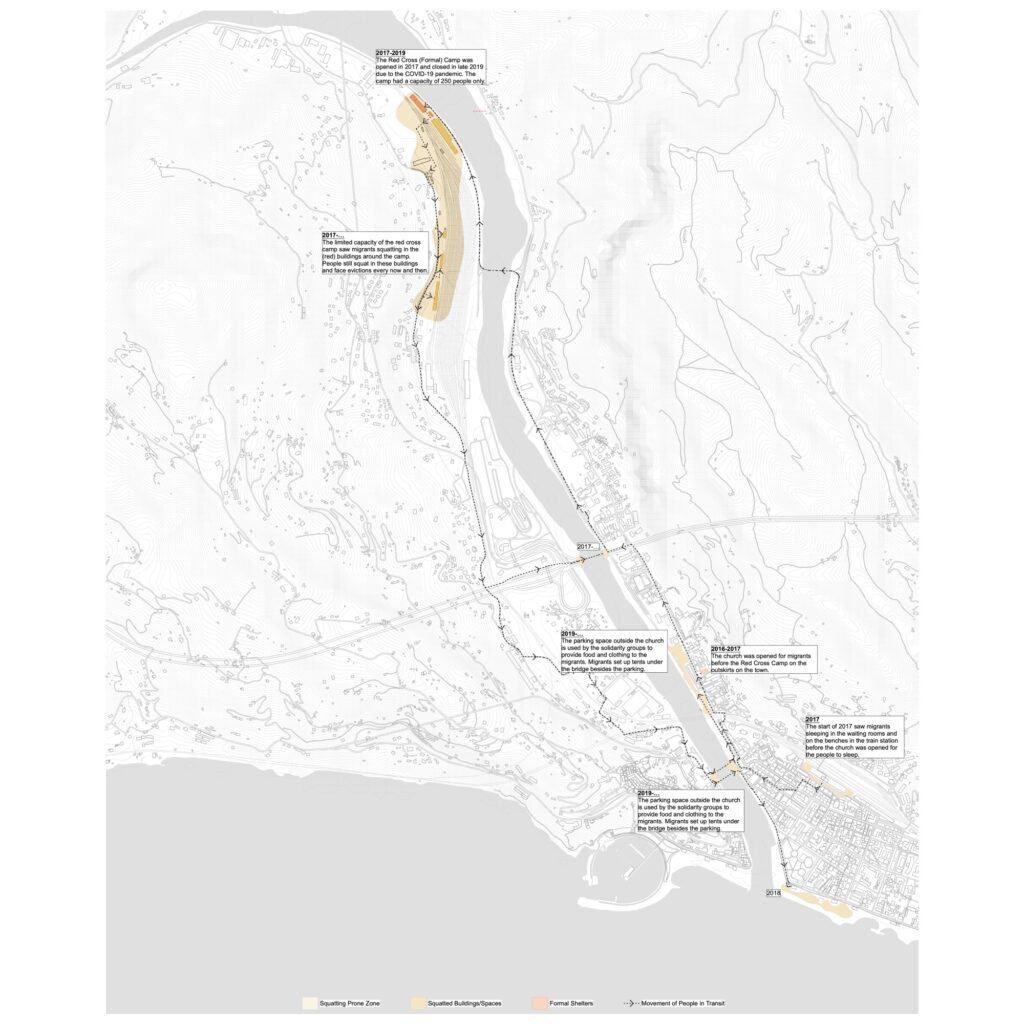

c. Reception Centers – A Response

Pertaining to the protests of the closure of the French border in 2015, a first-aid camp at the Ventimiglia Train Station was opened and later on, in early 2016, the people were located in the church of Sant’ Antonio as a refugee shelter. In July 2016, Ventimiglia saw the outset of an official formal camp by the Italian Red Cross for people entering the town, providing temporary shelter, support and assistance for those who had made it over time. The camp was opened at a maximum capacity of 250 people. The camp is surrounded and enclosed by a fence. The structure is as precarious as the everyday lives of the people living there. The rooms are metal containers with six bunks. Men, women and children are separated only by container blocks. The bathrooms are containers too. Only women and minors have a lockable bathroom. Next to one of the bathrooms is the camp mosque: a jumble of carpets sitting in the open air under the overpass, marked by a sign reading “place of prayer”.

There already exists a strategy of informal urbanisation that makes use of the temporariness of these informal spaces to make them useful and valuable. While it deals with informality, these spaces are still made to act within the system making them profitable. Martin Jenča in the book Meanwhile Spaces (2022) explains this with an example of closing off a place with a fence until it is finished is counterproductive. ‘It makes people walk around the fence for months if not years. And even if that fence mentions the hopes for the area’s future, what it communicates is – don’t come here, there is nothing for you.’ Such is the image created around the Red Cross Camps site in the border town of Ventimiglia.

Since the capacity of the Roya Camp was limited, could not cater to the influx of people and functioned on documenting and fingerprinting the people, many of the people especially those whose destination was not Italy, started squatting in the empty railway’s office building generally termed as ‘red buildings’ around the Red Cross Camp. The people that reside outside the camp cannot be thought of in isolation but their physical and mental distance from the solidarity spaces in the towns should be taken into consideration. These people try to cross the border on multiple occasions. Interestingly, it was not only the people squatting in the buildings and spaces who tried to cross but even those who were registered in the Roya Camp, since the state was taking up to 10 years to process the asylum applications.

Various methods are employed by migrants attempting the crossing. Among these, some harrowing accounts include unaccompanied minors resorting to climbing the perilous Death Pass, a rocky mountain range connecting Ventimiglia and Menton in France. This treacherous journey often proves fatal and necessitates scaling a border fence. In addition, other migrants attempt to pass through car tunnels or hitch rides on freight trains that pass near the migrant reception centre in Parco Roya.

In recent times, there has been a notable rise in arrests and returns on the French side of the border in Menton, pushing refugees to explore alternative, yet riskier routes to reach their destinations further north. These routes often lead them through the rugged and mountainous regions of the Alps. The escalating enforcement measures have compelled the refugees to take more dangerous journeys in search of safety and better opportunities. Not everyone who tries to cross is successful in the process. Some of them likely become susceptible to death.

In 2019 after some people in the camp had contracted the COVID-19 virus, in the hindsight of the pandemic, the camp was closed temporarily but since then it has not been resumed. Since then, the future of Parco Roya has remained uncertain. There have been proposals to convert the site into a commercial space, while others have suggested that it be repurposed as a reception centre for migrants.

2. Spatializing Migration

a. Politics of Formal and Informal Settlements

The spatial realities that condition the existence of migrants are plagued by the dialectics between the formal and informal in spatiality. The ever-changing state of spatiality of the migrants can be characterised as a flux. Often human beings try to seek aspired permanence to deal with this flux which eventually becomes the default condition when imagining a built environment (Mehrotra, 2017). This flux leads to the formation of smaller temporary settlements but, with time, these settlements in a way become permanent yet are considered temporary. It is the settlement infrastructure that becomes permanent, and the habitats become temporary as they are on the move. In other words, the people in transit are ephemeral and not the space. With this perspective, we understand that the refugee landscapes are formed by a series of settlements located in areas with political tensions. These temporary spaces can be perceived as ‘auto-constructed environments’ instead of what the commons refer to as ‘formal or informal camps’.

AbdouMaliq Simone in his book The Surrounds (2022), writes ‘The surrounds do not surround a given space, project, environment or ecology as a boundary limit or as some constitutive outside. They are not some alternate realities, just over there, just beyond the tracks or the near horizon.’

The politics of the formal camps revolve around the idea of providing shelter to the people in transit but after documenting them. These are the people who do not wish to settle in that state but somewhere else and as a reason to avoid documentation/fingerprint scanning. Due to this, these people don’t want to make their presence obvious, they are forced to squat in the buildings around the abandoned train station on the outskirts of the town facing evictions now and then. Some of them set up their tents in and around the space below the bridge in the Roya River in the town where the solidarity spaces such as food provisions and clothing provisions take up the surroundings of the bridge. This settlement below the bridge is a makeshift led by the migrants till the monsoons arrive and the river bears the water again.

In an interview with Philippa Nicole Barr for Domus, Mehrotra argues that we shouldn’t refer to cities as the formal and the informal city, but cities are kinetic which means they morph into one other – the temporal and the permanent. The kinetic city is temporary in nature. Here, openness and flexibility prevail over rigidity and rigour. Spaces in a kinetic city are consumed, reinterpreted and recycled. Informality is often associated with temporariness and these spaces are usually elided by the state, but they fail to realise that the city is a co-existence of the two worlds i.e. temporary and permanent spaces. Both these worlds transgress into each other but are often seen in isolation. These temporary spaces are often considered unprofitable, over-built, under-built or tacitly contested and will be normatively valuable (Simmone 2022, p.09).

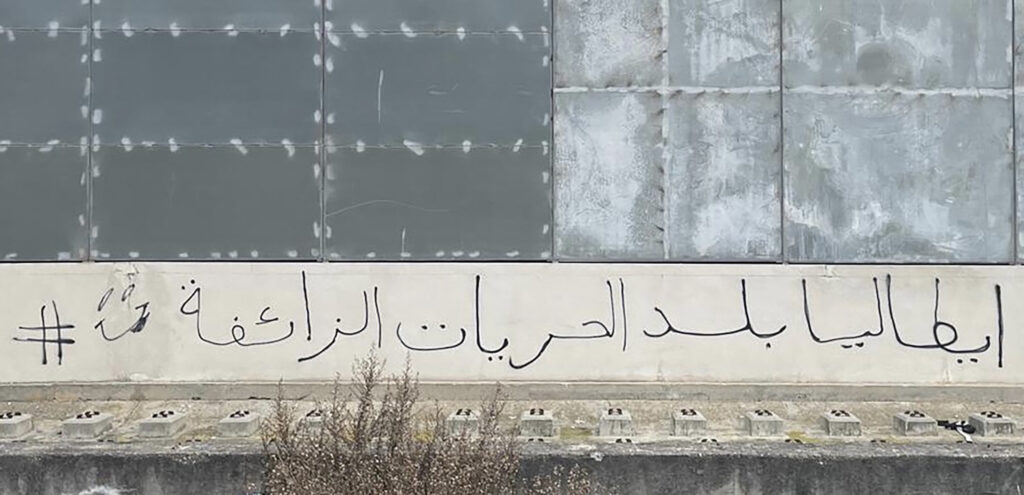

As people travel from the outskirts to the town centre, the journey is marked by the presence of graffiti, which serves as a visual representation of the wounds, traumas, and vulnerabilities experienced by those seeking refuge. In this way, graffiti becomes a transient expression of the struggles and emotions within Ventimiglia, creating impermanence on the static grain of the Ventimiglia town. These graffiti installations foster a sense of solidarity among the people, creating camps or shelters. It’s essential to note that there is a profound distinction between formal and informal camps, with informal settlements often being more hostile in nature compared to their formal counterparts. This is resonant with the idea that ‘Particular spaces are linked to specific identities, functions, lifestyles, and properties so that the spaces of the city become legible for specific people at given places and times.’ (Simone, 2004) Throughout the day, a significant number of migrants gather in informal settlements in the vicinity of the city centre. Over time, specific areas within the municipality, such as the southern corner of the beach or the railway lines, have gained acceptance as places of tolerance by both the police and the refugee community. These locations have become somewhat recognised as places where the refugees can gather without facing immediate eviction or persecution.

In June 2017, the municipality of Ventimiglia issued an evacuation order for the Roya River banks, leading hundreds of migrants to leave their camps. However, French authorities subsequently intercepted them and sent them back to the hotspot in Taranto, Italy. Witnessing the migrants’ determination to remain on the rocks where they had set up their camps and appalled by the violence they experienced, Italian and French citizens decided to support them. They came together to form a community known as the Balzi Rossi squat. This informal space marked the beginning of a series of solidarity initiatives that have appeared and disappeared in the vicinity of Ventimiglia from June 2015 until the present day. Each of these initiatives had its unique characteristics, objectives, and organizational structures.

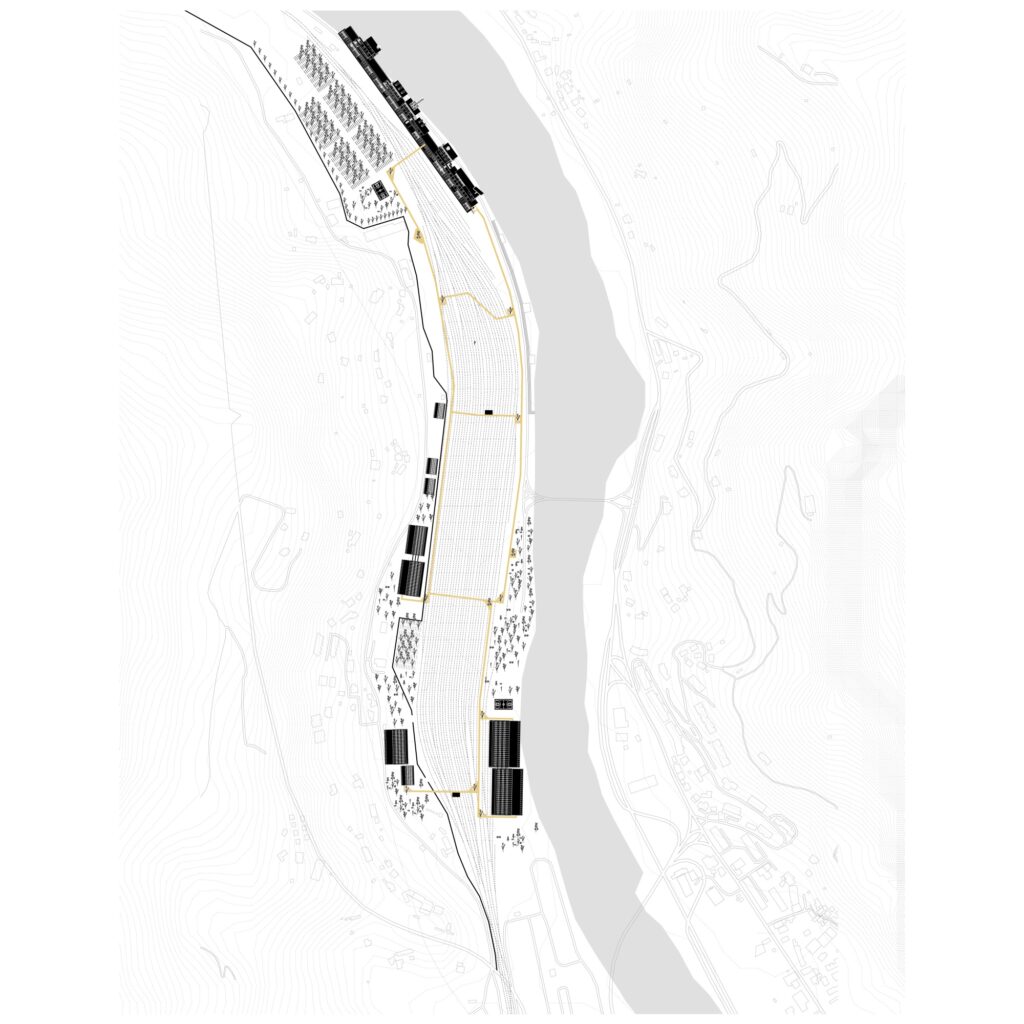

b. The train station at Parco Roya

Ventimiglia is served by two train stations; one being dedicated to the passenger trains and the other for the goods trains. The goods train station is located on the outskirts of Ventimiglia in the north. The Development Area has an elongated and flat conformation, includes a bundle of railway tracks, and borders to the east with the Roya River. The transformation district area has an optimal location, a stone’s throw from the border with France and near the Railway Station. The development area is located in a semi-central area of the Municipality of Ventimiglia, including in the perimeter of the freight railway station, now not used, in the Roya River Park. The intervention for its location and urban building functions represents the most interesting initiative of commercial-productive development to be carried out in the territory. The implementation is foreseen with affiliated building projects accompanied by an SOU. A flat area of 25 hectares was converted into a production and a commercial district. In recent times, the increased number of arrests and returns on the French side of the border in Menton has forced refugees to seek alternative and more dangerous routes to the north, especially in the more mountainous regions of the Alps.

3. Architecture of Impermanence

a. Squatting as a Practice

The migrants encounter numerous challenges, including barriers to accessing healthcare and struggling to find affordable, adequate, and humane living conditions. Additionally, they frequently face exploitation in the workplace and further hindrances when seeking healthcare services. Finding affordable and decent housing also poses a significant difficulty for them, among other issues. One critical problem is that they are often reluctant to report instances of labour exploitation due to their fear of being arrested, detained, and subsequently deported, which further exacerbates their vulnerability and lack of protection.

The process consists of a set of interventions that affords a realm of possibilities for reception and homemaking techniques for people in transit. Within a state of cyclical hostility and oppression, the selected modes of intervention afford a sense of optimism. Through reclamation and re-appropriation of spaces to provide for one’s needs, the people in transit can interrogate existing power structures and reshape an authority that one may face. The affordance of agency over one’s space allows for a quality of empowerment through asserting one’s rights and identities. An inquiry begins into the dialectic relationship between mobility, stasis, and authority by interrogating the symbolic and physical manifestations of post-industrial infrastructures. How may one mobilise various possibilities of reception and home through a practice of subversion, engaging with the materiality of a post-industrial infrastructure? This is defined as an entry point into the selected site and the project.

The type of (squatting) architecture that is characterised by its self-made, unplanned, and spontaneous nature is often created with limited resources and a low budget. It is frequently constructed using recycled materials found on the streets or sourced from other squats. These features make it easily identifiable and grant it unique qualities not commonly seen in conventional “normative architecture.” The use of recycled materials contributes to its authenticity, material diversity, and raw expression of creativity. However, the impermanent nature of this architecture is noteworthy. Following an eviction, the structures are often swiftly demolished, turning them into an ephemeral and precarious form of architecture. It exists temporarily, with its existence being transitory and subject to rapid disappearance or transformation once again. This transient aspect adds to its distinctive character and reflects the dynamic and ever-changing conditions of the spaces in which it emerges.

The project speculates the next 30 years of reappropriation. In the first few days, where the people after be entering the building, remove some of the panels and cover them with tarpaulin sheets which can be easily procured from the truck & lorry parking near the site. The tarpaulin sheets are not easy to cut and break into the space, providing time for the people squatting in the building to evacuate. Later on, all the empty squatted buildings in the vicinity could be reapportioned and connected to form a community within itself. As of now, squatting in Italy does not possess legal recognition, unlike certain other countries. However, with the passage of time and the influence of spatial thinking, this situation has the potential to shift and evolve. Legal perspectives and attitudes towards squatting may undergo changes, opening up possibilities for different approaches and considerations in the future.

In his book Ephemeral Urbanism (2017), Rahul Mehrotra writes, ‘Understanding the settlements of refuge under the rubric of an urbanisation of ephemeral is fundamental.’ These ephemeral spaces are very different from the temporariness of the various typologies viz. religious, disaster, military, refugee etc but functionally, can be looked at as the same.

b. Concept of Mobility

The selected site entitled “Parco Roya” exists outside the town of Ventimiglia, Italy. The socio-economic histories of this site are acknowledged as the post-industrial infrastructure which at one point embodied a transboundary space that contributed to the trade, economic and cultural vitality within Ventimiglia. The site’s location, close to the French border, has also made it a focus of controversy and tension between Italian and French authorities. In recent years, the Parco Roya site has become a symbol of the broader challenges and complexities surrounding migration in Europe.

As the number of refugees and migrants seeking asylum in Europe continues to grow, this site was originally established as a Red Cross Camp for migrants entering Ventimiglia but has since been left uncertain, caught between the possibility of commercialisation or conversion into a reception centre for migrants. The project aims to reimagine this space as a reception centre. Parco Roya is looked at as the physical manifestation that holds a space in suspension and forms a lens into the political milieu of its state.

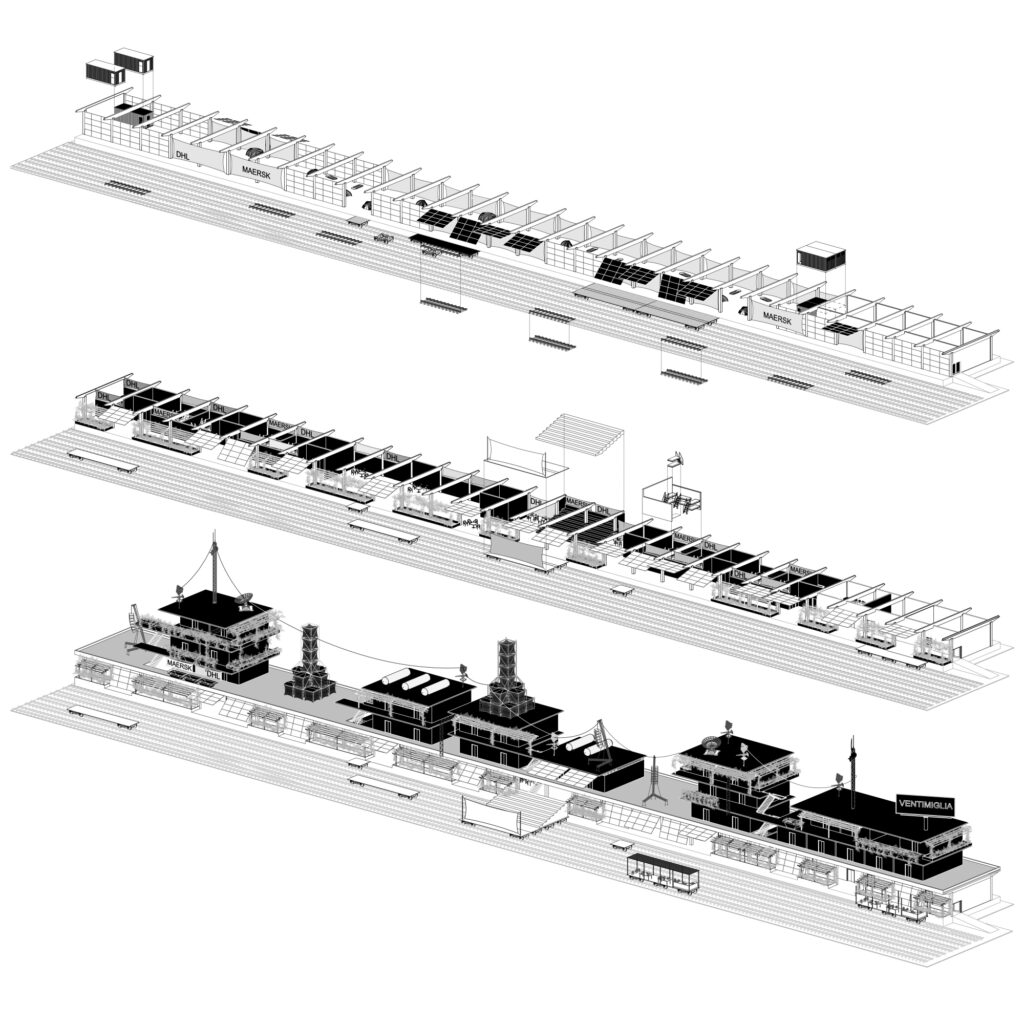

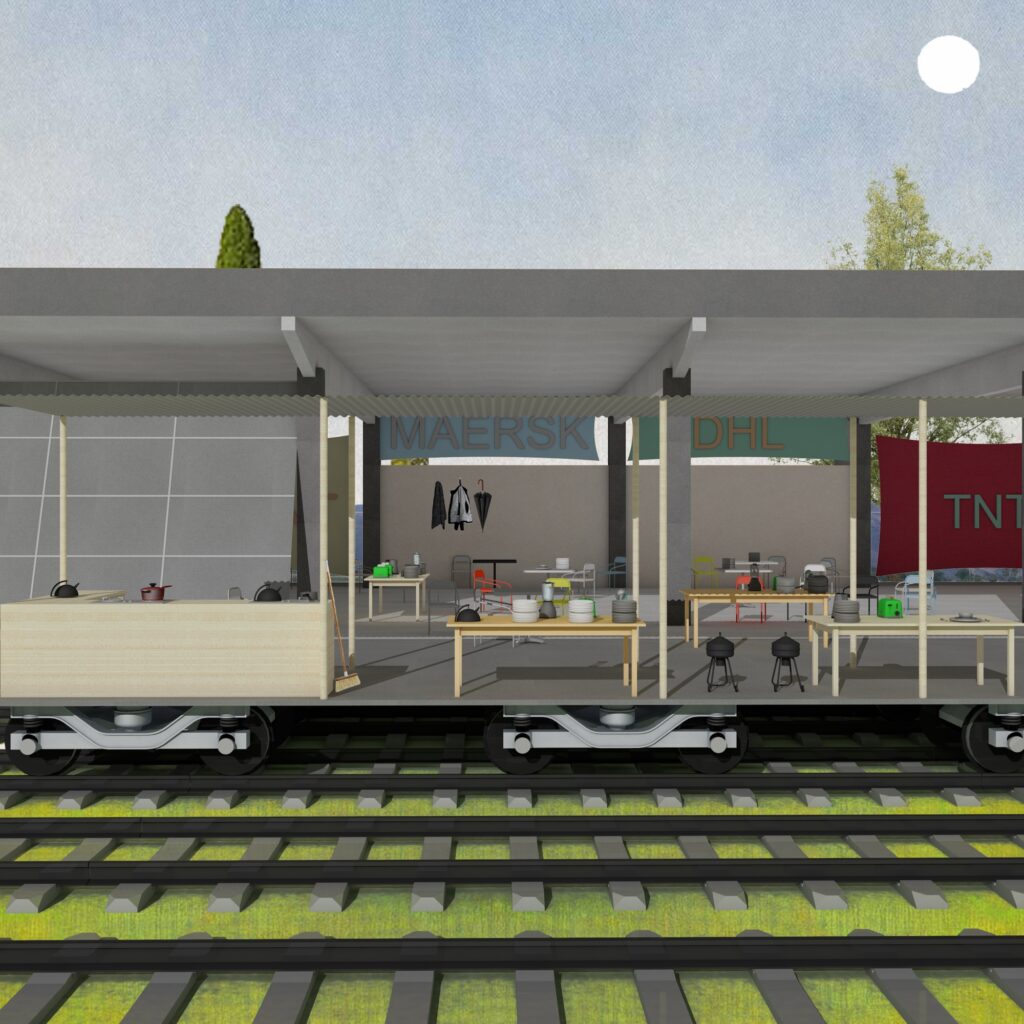

Cedric Price’s project in 1964, ’The Potters Thinkbelt’ revolves around utilising existing ruined buildings as a foundation for new structures capable of accommodating adaptable modules based on changing needs over time. The concept embraces the notion of an unstable and open urban canvas, where the territory continuously evolves, and conditions and requirements fluctuate. The approach envisions a dynamic and flexible architectural solution that can respond to the ever-changing demands of the environment and society. Thinking along similar lines, in the case of Parco Roya, a transboundary network can be formed that connects different groups from different parts of Italy and France and the mobile train units can be catering to all of them. Since the abandoned building used to be a good’s train station, the building and the existing rail network, which are static and mobile respectively, complement each other. The building is being squatted to create the habitual space while the rail network is being reappropriated to create spaces for the community that act as mobile units that can also carry an infrastructural function of transporting essentials during the time of need. These spaces can involve community kitchens, educational programs, forums and so on. Also, as it happens to be the last station in Italy entering France, it acts as a hub for a transboundary network.

Adding to the element of mobility is the speculative nature of the project which tries to imagine the site 30 years down the line. Here the concept of mobility is expanded to include various forms of transportation through sea and air. The idea is to expect the mobile units to be fundamentally reproduced in these other forms of transportation to achieve the same objective of servicing different sites of relevance, thus building a self-sustainable network of which Ventimiglia is projected to become a part.

c. Reappropriation as a Method

The intervention lies in reimagining how one may appropriate the existing infrastructure within the Parco Roya to their needs. The methodology for the Architecture of Impermanence involves two stages. The first one is documenting and visualising the current condition of the infrastructure in Parco Roya, through mapping its historical and contemporary function, we can establish a foundation of understanding that is rooted. Secondly, identifying subversive practices that may allow for appropriation of the selected site within Parco Roya. Exploring the ways an individual may reclaim, appropriate and repurpose the space by engaging with the materiality of the current infrastructure, through identifying methods and techniques one may use to assert agency and reshape a site towards their needs and aspirations.

Through the provision of a toolkit/taxonomy of necessary tools, mapping of infrastructures and re-use of waste material, and informed from the methods and techniques, through the intervention, the possibilities and selected programme functions that may be mobilised within the site are reimaged. Therefore, historical and contemporary functions of the site act as the ways one may appropriate the space. Furthermore, the programme of function will be influenced by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs physiological, safety and security, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization. This will act as an apt basis for the evolution of a space of reception.

d. Speculating Architecture through Material

The cyclical and ever-changing nature of informal settlements, characterized by movement, stasis, and uncertainty, presents a challenge. However, a range of material practices offers a spatial resolution that confronts socio-cultural realities. The engaged site lies in a constant state of uncertainty as people in transit exist in constant flux. However, amid these realities lies an opportunity for spatial interventions that may provide agency over one’s living conditions and reality. The intervention lies in engaging in the possibilities of use of existing material of the selected site.

The inherent material versatility, economy/viability, and functionality or ease of handling and construction afford the ability for individuals to create and reclaim spaces. Employing textile design within architectural contexts may allow one to transcend traditional building practices and approaches. (i) The affordability of textile material democracies access to the building material which generally consists of high barriers to entry, this affords individuals (especially those with limited resources) the ability to integrate textile practices in their architectural context. (i) The versatility of textile material through its innate malleability, lightweight nature and diversity of material contexts, – along with the ease of connecting or attaching the material to form an enclosure allows for a realm of possibilities when applied to architecture contexts.

Textiles within the context of the proposal may mediate between existing infrastructure (Parco Roya) and material (mild steel, aluminium and metal) to form interior and exterior spaces (whether it’s a partition between rooms or a temporary surface for an exterior outer wall. These semi-permanent material interventions may help foster a sense of empowerment and control over one’s living space and reimagine one’s relationship with reception spaces.

The intimate historical relationship between textile practices and architecture has existed since Kurt Foster, “Art and architecture first intersected when man learned to fasten textiles to a post” (KW Forster, 2002, p 51) as the act of connection and binding of material to physical objects to form a specific space. A broader perspective is adopted when considering the conception and traditional roles of textiles in relation to architectural contexts. Often seen within temporary to permanent construction applications: specifically, within shading, reinforcement, membrane construction and geotextiles textiles withhold the ability to adapt and be formed to a specific function.

The contemporary relationship between textiles and visual practices transcends architecture and has undergone significant transformations across mediums such as installation, painting, sculpture and various visual cultures. Through processes such as “burying, soaking, dyeing, and embedding, the textile-based works record its environment and process through its marks producing a plane that embodies themes of political, and environmental violence, erosion and toxicity (Brazil, K.,2022, Dala Nasser at V.O curations).

The research methodology towards engaging with the socio-spatial conditions of the site: Parco Roya employs active engagement with the existing materials, specifically the material of Aluminium or metal that monolithically wraps the secured infrastructure. The use of metal acts as a durable, resilient way of producing barriers to hinder access to the site for people in transit. Bound by the process of welding, more especially spot welding which involves using a type of eclectic resistance to bind various sheets, acts as an efficient and feasible process that can be done with mobility and with minimum equipment, allowing it to be an ideal process in securitization. The site through its securitized state barricades people in transit from using the space for their desired function, thereby perpetuating a condition of hostility faced by migrants. This raises questions on the ways the material can be weaponized demonstrating broader challenges surrounding migration within Ventimiglia. The Design intervention lies in proposing ways one may engage with welding processes and reappropriation of metal and aluminium to produce spaces for living. The reappropriation proposes ways one may leverage existing surrounding infrastructure (train lines, warehouses and transport networks) to create spaces needed to sustain a hospitable environment. These spaces may include sleeping rooms, community kitchens, multi-faith prayer spaces, and screening rooms as seen within the drawings.

The methodology towards its display employs elements and techniques rooted between abstraction and diagrammatic presentation. Looking beyond the activity of selection, organisation and presentation of materiality and an architectural proposal in isolation, a palimpsest approach towards encouraging curiosity from the viewer was employed. The aim was to set an environment for one to situate their curiosity within the narrative of the site (Parco Roya) by employing the medium of installation. The installation consisted of Six (6) mild steel panels, mild steel bars, textile and Four (4) concrete breeze blocks to form a freestanding work. The use of this material as a palimpsest for the research allows us to communicate the observations, mapping and proposals within a material reality. Moreover, the methodology allows viewers to directly engage with the possibilities of material and its ability to inhibit or provide possibilities for space.

Conclusion

The project observed and investigated the interplay between mobility and stasis through the lens of materiality and methods of subversion to confront the social, political and cultural realities faced by people in transit within Ventimiglia. The spatial entry point of “Parco Roya” a monolithic post-industrial infrastructure afforded us an opportunity to confront the cyclical state of hostility and oppression, Architecture of Impermanence aimed to provide a theoretical and speculative methodology that may imagine a reception space as a site of possibility and model of habitation. It stands as another way to think about migration, especially in heavily policed restrictive spaces. Selected practices and approaches of subversion through reimagining the uses of metal, aluminium mild steel, and existing infrastructures (train lines, abandoned structures, found debris and materials) provide a methodological approach towards the way an individual may activate one’s space – interrogating existing power structures and reshape their authority. This practice of reclaiming and reappropriating space allows one to reclaim one’s identity, space and authority. The site Parco Roya acts as a microcosm for broader complexities of this socio-spatial condition surrounding migration within Europe, especially in the case of the Franco-Italian border.

References

Balli, F. (2021) ‘Ventimiglia 2015-2018: a story of solidarity by Anna Finiguerra’, Duty of care · Italy-France migration, 16 April. Available at: https://italyfrance.hypotheses.org/80 (Accessed: 12 July 2023).

Border town: hope and fear in the ‘Calais of Italy’ – The New European (no date). Available at: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/border-town-hope-and-fear-in-the-calais-of-italy/ (Accessed: 23 July 2023).

Schengen Area (no date). Available at: https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/policies/schengen-borders-and-visa/schengen-area_en (Accessed: 2 September 2023).

Chiodo, S. and Dotti, A. (no date) ‘THE BRUTAL SIDE OF THE FRENCH RIVIERA’.

Corboz, A. (1983) ‘The Land as Palimpsest’, Diogenes, 31(121), pp. 12–34. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/039219218303112102.

Da Stazione a Campo Croce Rossa Ventimiglia videomap/From Train Station to the Red Cross Camp (2019). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1rzqltnLlIY (Accessed: 24 July 2023).

De Leon, J.P. and Cohen, J.H. (2005) ‘Object and Walking Probes in Ethnographic Interviewing’, Field Methods, 17(2), pp. 200–204. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05274733.

(Dead) end of the journey: what happens when migrants reach border towns? (2017) New Internationalist. Available at: https://newint.org/features/web-exclusive/2017/12/18/migrants-border-towns (Accessed: 24 July 2023).

Digital, S. (no date) The Exacerbation of a Crisis: The impact of COVID-19 on people on the move at the French-Italian border, Save the Children’s Resource Centre. Available at: https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/the-exacerbation-of-a-crisis-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-people-on-the-move-at-the-french-italian-border.pdf/ (Accessed: 6 July 2023).

[Feature] The rotten truth behind Menton, ‘the pearl of France’ (2023) EUobserver. Available at: https://euobserver.com/migration/156740 (Accessed: 23 July 2023).

Goodfellow, M. (2020) Hostile Environment: How Immigrants Became Scapegoats. Verso Books.

HORIZONTE – Journal for Architectural Discourse No. 10 – Resistance by Initiative HORIZONTE – Issuu (2015). Available at: https://issuu.com/horizonte-architekturdiskurs/docs/151110_h10_layout_plakat (Accessed: 2 June 2023).

https://www.facebook.com/InfoMigrants (2017) Ventimiglia: a bottleneck for migrants, InfoMigrants. Available at: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/4889/ventimiglia-a-bottleneck-for-migrants (Accessed: 12 July 2023).

https://www.facebook.com/InfoMigrants (2020) Migrant reception camp in Ventimiglia closes, InfoMigrants. Available at: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/26391/migrant-reception-camp-in-ventimiglia-closes (Accessed: 26 July 2023).

https://www.facebook.com/InfoMigrants (2022) Migration: Border controls stepped up between France and Italy, InfoMigrants. Available at: https://www.infomigrants.net/en/post/44713/migration-border-controls-stepped-up-between-france-and-italy (Accessed: 21 July 2023).

Marko, P. and Lisa, R. (2022) Meanwhile city: how temporary interventions create welcoming places with a strong identity. Bratislava, Slovakia: Milk Studio.

Mehrotra, R., Vera, F. and Mayoral, J. (2017) Ephemeral Urbanism: Does Permanence Matter? List – Laboratorio Internazionale Editoriale Sas.

Mezzadra, S. and Neilson, B. (2013) Border as method, or, the multiplication of labor. Durham: Duke University Press (Social text books).

Mobility justice : the politics of movement in an age of extremes | WorldCat.org (no date). Available at: https://www.worldcat.org/title/1044776009 (Accessed: 20 July 2023).

Riccardo Badano, “Hostile Environment – the design of the anti-migrant hostility along the Western Alpine Arc” (Unpublished MA Diss., Goldsmith University of London, 2017-2018), 24-25.

PLATFORM: Discussing Futurity in Architecture (2021) PLATFORM. Available at: https://www.platformspace.net/home/discussing-futurity-in-architecture (Accessed: 15 June 2023).

‘raumlabor » [Working on] Common Ground’ (no date). Available at: https://raumlabor.net/working-on-common-ground/ (Accessed: 2 June 2023).

Refugee Crisis: Ventimiglia known as Italy’s ‘Calais Jungle’ (2017). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IhmkZD3qMN4 (Accessed: 24 July 2023).

Simone, A.M. (Abdou M. (2004) ‘People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg’, Public Culture, 16(3), pp. 407–429.

Squatting as a Spatial Practice (2019) Architecture of Appropriation. Available at: https://architecture-appropriation.hetnieuweinstituut.nl/en/squatting-spatial-practice (Accessed: 2 June 2023).

Stewart, H., Gokee, C. and De León, J. (2021) ‘Counter-infrastructure in the US–Mexico borderlands: some archaeological perspectives’, World Archaeology, 53(3), pp. 469–485. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999854.

The Land as Palimpsest by André Corboz (956ES) — Atlas of Places (no date). Available at: https://www.atlasofplaces.com/essays/the-land-as-palimpsest/# (Accessed: 6 July 2023).

The making of migration : the biopolitics of mobility at Europe’s borders | WorldCat.org (no date). Available at: https://www.worldcat.org/title/1129233565 (Accessed: 20 July 2023).

‘THE THINKBELT: THE UNIVERSITY THAT NEVER WAS’ (2014) Discover Society, 1 July. Available at: https://archive.discoversociety.org/2014/07/01/the-thinkbelt-the-university-that-never-was/ (Accessed: 2 June 2023).

‘The worst refugee camp on earth’ – BBC News (2018). Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8v-OHi3iGQI (Accessed: 24 July 2023).

Victoria and Albert Museum, D.M. [email protected] (2014) Disobedient Objects: How-To Guides. Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 2RL. Telephone +44 (0)20 7942 2000. Email [email protected]. Available at: http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/exhibitions/disobedient-objects/how-to-guides/ (Accessed: 2 June 2023).