Nashik’s untapped potential with existing urban public space

The Smart Cities Mission was launched by the Government of India in 2015, with a focus on promoting urban renewal in Indian cities to help make them more liveable. A total of 100 model-cities were selected to be developed as Smart Cities, based on their Smart City Proposals (actionable urban development projects) via a selection competition.1 Nashik, a tier-ii city in Maharashtra was also selected to be developed as a Smart City under this centrally funded mission.

Nashik is called the ‘Onion Capital’ and ‘Wine Capital’ of India, as a lot of large-scale agricultural activity especially related to onions and grapes is prevalent here. Traditionally, it is an ancient city that is famous for its temples and pilgrimage sites. Owing to its rich heritage, most public spaces in Nashik are located around the heritage areas in the old city along the Godavari river ghat, while other public spaces have developed around temples and markets spread across the city.

In the late 90’s the NMC (Nashik Municipal Corporation) held an architecture competition for creating a new public space, called the Phalke Smarak; a memorial celebrating a prominent figure hailing from Nashik – Dadasaheb Phalke, also called the ‘Father of Indian Cinema’.2 This competition provided an opportunity to renew the urban identity of the city and had the potential to define a new typology of public spaces in Nashik.

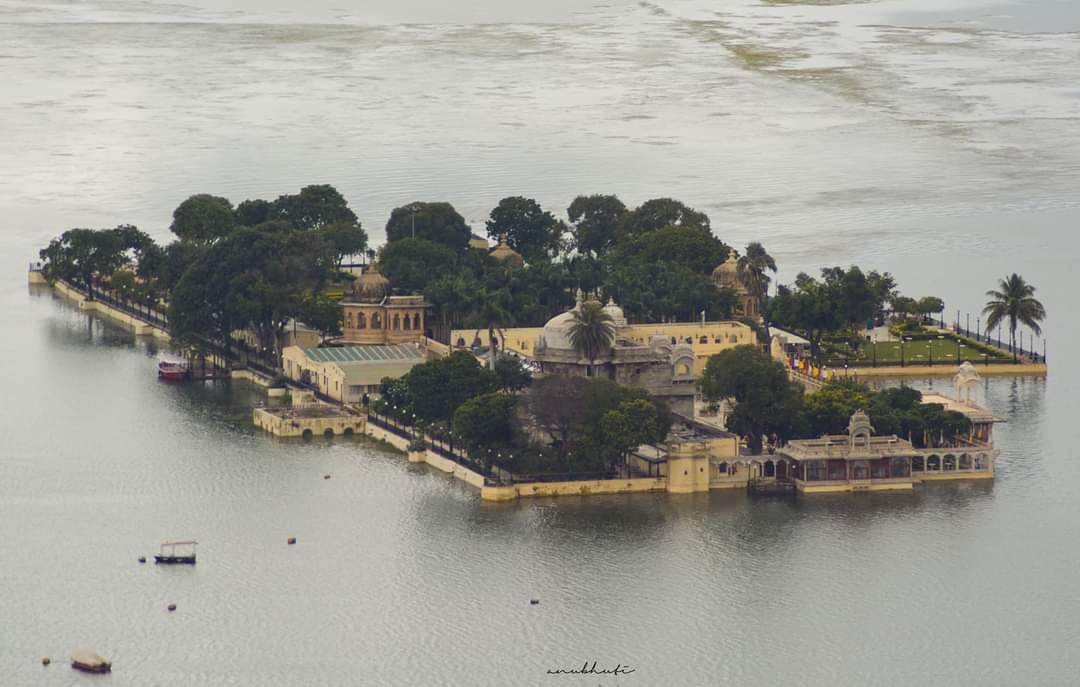

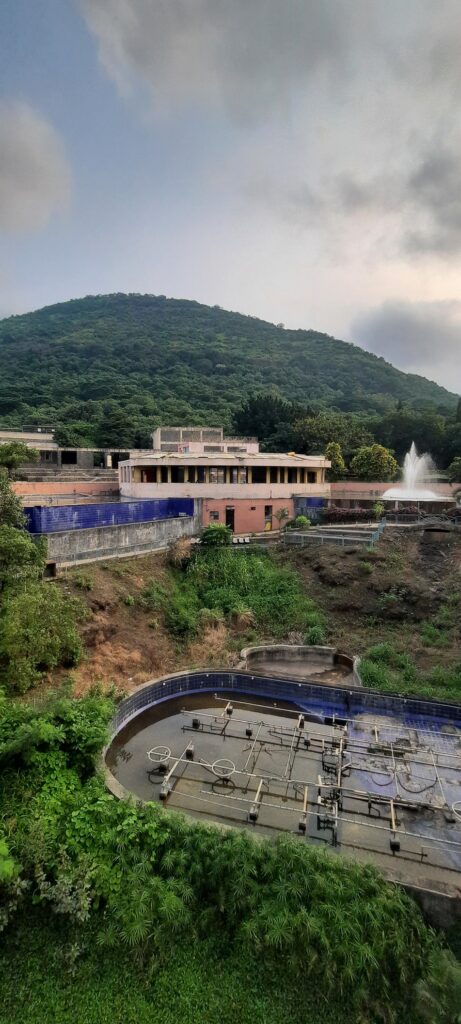

The winning concept envisioned the Smarak as ‘A Memorial in a Park’, since the 30-acre site considered for the project was located within the area designated as an amusement park, at the base of the famous Pandav Leni (an ancient hillock with Buddhist hand-carved rock caves). This proposal was pitched by the Mumbai based architecture firm, Group Seven Architects and Planners.3 By late 2001, the Phalke Smarak; Nashik’s new urban public space was opened to the public. It had a Buddhist vihara (meditation hall), exhibition halls, an auditorium, a cafeteria, food-court, amphitheatre, rent-able guestrooms and various gardens spread across the site. Other features included a water park and open-air musical fountain that were widely enjoyed as unique attractions. Although the project was located away from the main city; during the initial few years it got an active response, and the average footfall was high.

Despite getting traction and given the scale of the new public infrastructure – the quality and curation of cultural events hosted at the Smarak were mediocre from the start. One can also reflect that the location of the Smarak provided an interesting opportunity as a public venue – that was peaceful and close to nature, while also buzzed as an urban cultural hotspot. Sadly, the full potential of Phalke Smarak was never realised and remains untapped till date.

In a span of less than five years after its inauguration, the Smarak saw much lesser visitors. Inadequate maintenance by managing bodies was considered the main reason for the loss of public interest in the project.4 As of today, the cafeteria and food court have shut down, and no food/water is available inside the premises. The main exhibition hall showcases the few remnants of the original exhibition dedicated to the life of Dadasaheb Phalke; and no events are held in the amphitheatre or auditorium spaces. The water park and musical fountain are non-operational and have been ageing to ruin. Only the amphitheatre steps, meditation hall and garden spaces are occasionally graced by visitors. What was once a promising public space for Nashik city, can now be recognised as a decaying ‘urban void’.5 (The term ‘void’ means ‘being without’, and for simplicity an ‘urban void’ can be interpreted similarly as an ‘urban vacuum’.)

Images showing: the interestingly designed but unused exhibition halls (LHS); non-operational musical-fountain pit with a backdrop meant for projecting images/films (centre); and shut down food-court huts covered in rust (RHS). [image source: author]

The core focus of initiatives like the Smart Cities Mission is on urban renewal in Indian cities by improving the state of urbanisation using smart solutions. The projects pitched by Nashik city under this mission do not include any renovation proposal of the dilapidated Phalke Smarak. From an urban design perspective, public spaces are considered powerful tools in making cities more liveable. Given the general lack of public spaces in Indian cities, the massive failure of such existing public spaces comes as a hard-hitting reality.

According to local newspaper articles, NMC officials have been working on plans for improving the state of the Smarak (outside of the Smart Cities funding) by renovating it into a tourist attraction like the Ramoji Film City in Hyderabad.6 While such a plan may envision a better future, the potential that the Smarak holds as a multi-faceted urban public space is being overlooked for the second time.

There is an obvious gap in the vision of the authorities that implement and manage such projects, and the end user that is unable to engage effectively within their framework. In an attempt to fill this gap, the way forward points towards implementing practices like ‘placemaking’ through ‘public engagement’. While the concept of such urban development is relatively new to Indian cities, there are several international examples to draw from, that have successfully incorporated community-driven projects.7

By adopting such an approach with reviving the Phalke Smarak – right from renovating the infrastructure, creating new facilities, involving relevant stakeholders, to generating a profit generating management plan – we can aspire to create effective change by harnessing the power of people. Giving the public its rightful say in making existing space – a ‘place’; may be the smartest solution for effective urban renewal in this case and could pave the way for future public space development in Nashik and other Indian cities.

[image source: author]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, Government of India: Smart City

- Encyclopaedia Britannica: Biography, Dadasaheb Phalke, Jul 2023

- Group Seven Architects and Planners: Dadasaheb Falke Memorial Park

- Times News Network, Nashik: 15-yr-old Phalke memorial lies in a shambles, Apr 2016, TOI

- Anubhav Borgohain: Urban voids, Apr 2022, Urban Design Lab

- Tushar Pawar, Nashik: NMC invites bids to renovate Dadasaheb Phalke Memorial, May 2023, TOI

- Ethan Kent: Leading Urban Change with People powered Public Spaces, June 2019, PlacemakingX

Note: All the images are shared by the author.