Source: Tamburelli, P. P. (2022, May 10). On Bramante. Amazon. https://www.amazon.com.au/Bramante-Pier-Paolo-Tamburelli/dp/0262543427

About Baukuh

SK: Hi, Pier. Please introduce yourself and your office, Baukuh, to the readers.

PPT: My name is Pier Paolo Tamburelli. I am an Italian architect and a professor at the Vienna Technical University. I am one of the founders of Baukuh, an office based in Milan that is run, at the moment, by five partners. Baukuh was founded in 2004. We have been doing public and private buildings in Italy and the rest of Europe, but we also research and have been participating in biennales and exhibitions. Many of the partners of Baukuh have been a part of the editorial board of San Rocco, an independent architectural magazine that lasted roughly ten years, or maybe a little bit less, and was closed a couple of years ago.

On Baukuh’s approach

SK: What is your general approach to most projects that come your way or to the studio? Is there a general way?

PPT: I think there is no method. Of course, we are always trying to be as attentive as possible to understand not just the immediate physical context but also the political, economic, cultural, and legal context in which we operate. We try to operate in that space with great precision, not necessarily trying to make statements but trying to learn from what we see. Often, the things we learn in certain places are reused in other places. In the end, I would say we are a relatively traditional architecture office. But at the same time, as we are five partners, there are different inputs and imageries (although we are not so diverse, being all white, Italian, and lower-middle-class). We produce architecture in this limited but plural context, in which we discuss and argue about the projects that we are designing; these discussions normally evolve by bringing in precedents from the architecture of the past. Here, the architecture of the past is meant in a loose and low-profile way—simply as something that has already been built and that we encountered (either in reality or in photos or drawings), which we think can be re-employed in the specific case we are confronting.

SK: On that note of arguments on the architecture of the past, two chapters in your book On Bramante stand out with respect to style and architecture: “Classicism versus Eclecticism” and “No Style.” Does the thesis from these chapters find its way into the practice of Baukuh as a group?

PPT: Classicism and Eclecticism are certainly something that the office works on because the office uses very different sources. Even though the material gets filtered through different people, there is a desire to produce a composed architecture, i.e., an architecture that is multiple but not messy. This not only requires a plurality of the sources but also a certain discipline in putting them together.

It is about finding a formal agreement at the level of the object and between the people who are designing it—an agreement that is not only valid for the designers but also for the clients, the administrators, etc.

I think that the micropolitics that appear during the process of building make architecture intimately political, even if you choose not to engage with it in purely political terms.

On the idea of practice

SK: How do you see architectural practice when you have also been teaching at a university, writing several books, running a magazine, doing research, etc., while running a practice?

PPT: Well, these three forms of practice involve very different responsibilities that come with them. When you are teaching, you are simply a state employee. There is specific freedom in academics, but there is also responsibility. There are certain things that you shouldn’t do in such a context. At TU Vienna, I teach around five hundred students in the first year, the first semester’s introductory course (see Grundkurs: What is Architecture About?). This means telling students at the very beginning of their career what architecture is about. It is not always easy to combine certain accessibility and ease with intellectual rigour and sharpness.

While teaching at a university allows you to choose (at least to a certain extent) the kind of work that you want to do, the practice has a strange randomness that forces you to do things that you don’t want to do or wouldn’t consider doing. It is very refreshing, but it requires a lot of tolerance and even more humility.

When it comes to writing, I would say I fundamentally write two types of things: boring stuff for the office and academic texts (which allow more freedom). Writing competition reports and applications are probably my main job at the office. It is very different from writing a book, but I think that writing boring things teaches you a lot. Somehow, by writing a massive amount of boring stuff, you learn how to write relatively more interesting things. The book On Bramante was important to me, but I am not writing anything similar; I do not have any urgency to write right now. It is a little bit like what happened to San Rocco; the moment in which everyone started to like it, I kind of started liking it less, or at least I thought that we said what we needed to say.

On Form and Formalism

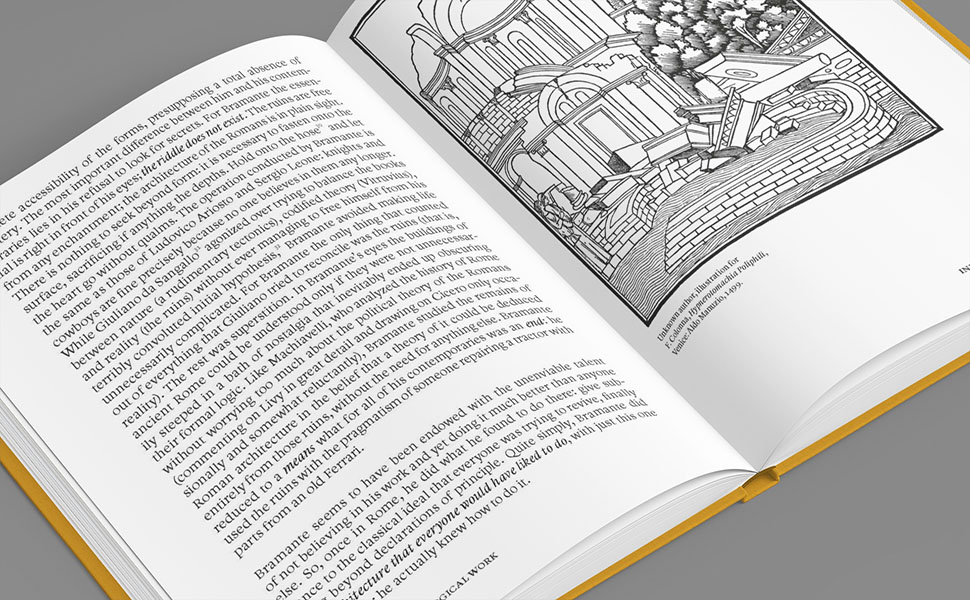

SK: For the next part, I want to focus on certain points from On Bramante that I found very interesting: the book is structured in two parts, the first being ‘Logical Work’ and the second part being ‘Political Work’. ‘Logical Work’ deals with the question of form, and ‘Political Work’ deals with the question of the relation between space and politics, where space is politicized by posing it as a void for something to happen on the one hand and as an apparatus to order that happening. In that sense, I read the book also as an ideation on the fundamental questions of form and space in architecture. My question then is: What is your idea of form and space?

PPT: Well, I don’t know if I would be able to give you a direct answer. This is also probably the reason why I wrote the book On Bramante.

I think architectural form is a hardening or crystallization of certain behaviours, where the behaviour belongs to people and the form belongs to the building.

Being big and immovable, buildings are rigid things that determine ways of acting for human beings. This relation, the influence of space and light conditions on human actions and gestures, is difficult to define; I would say that the history of architecture is nothing but the search for an interpretation of this relation. What I can say is that the form is the border that defines what is possible inside and outside of it, but this border or form is somehow clumsy, so it is difficult to predict what is really allowed and what is forbidden by form. Hence, it is this duality of looseness and rigidity of form in architecture that can open up possibilities that are different from the usual. It is possible to say that forms are infinite and, at the same time, that they are relatively limited, as humans spontaneously recognize and remember only a few simple forms. This is why, in our work, we use geometrical forms like circles and squares—not for their metaphysical meaning whatsoever, but because these forms are easily recognizable—they are, so to speak, evident. That is my very banal theory of form—that they can be used to measure (which in the end is the only thing that architectural form can do) certain behaviours and gestures of certain people.

SK: What is your approach to the idea of formalism, since it is something that is not really in fashion?

PPT: I think formalism has never been in fashion and has always been used to describe an excessive interest in form, which implies forgetting everything else. I think that, to a certain extent, we are a formalist office; we think that form is more important than content. We think that any architectural problem is interesting, independent of scale, type, and function. In the end, the only thing architects can work with is form.

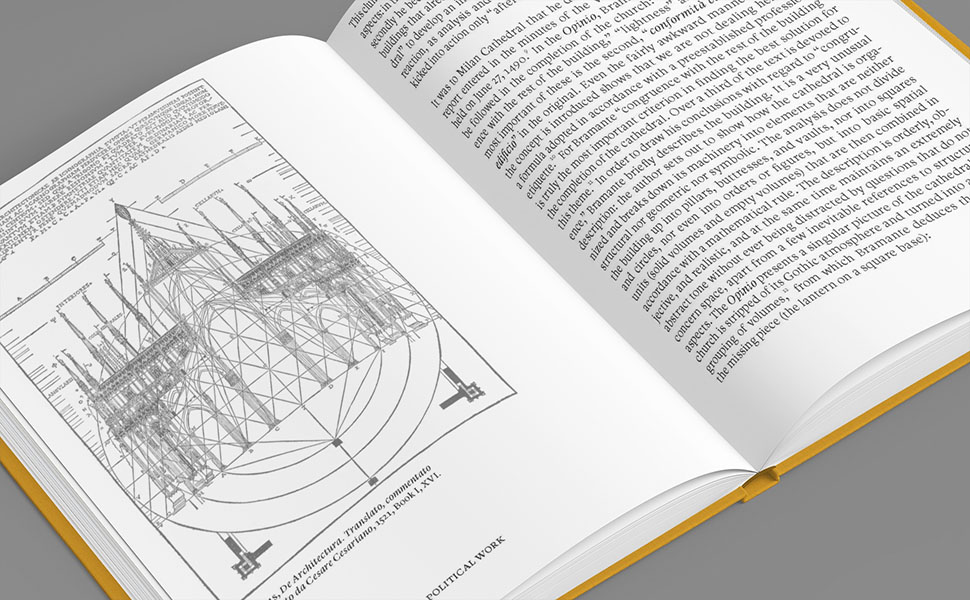

SK: While dealing with the design of St. Peter’s Basilica, the question that Bramante asks is how do two kinds of forms meet? Do you think that, in a conceptual sense, architectural work is limited to this kind of operation?

PPT: Well, Bramante’s assemblage for St. Peter’s is quite a complicated operation, and at the same time, it is a radical reduction of the problem that, utilizing this “pure assemblage,” is de facto deprived of symbolic meaning. I would say that we never “assembled” things in such a paradoxical and radical way. What we do is put things together and identify the problems that arise from that. For example, if the scale of the assembled objects is different, adjustments will have to be made to the geometry. Hence, assembling becomes a way of knowing architectural objects by putting them in a new and strange situation.

SK: The works of Ungers, Rossi, and Koolhaas, for instance, have a certain degree of rationality and critical thinking. However, the experience of the buildings is very simple, as compared to someone like Peter Zumthor’s buildings, where spaces feel more “sensual.” Do you think that there is a strange separation that abstraction brings in terms of the qualitative aspects of space?

PPT: I don’t think a sensual component of architectural experience is necessarily in conflict with a more rational definition of space. Bramante is a good example because it has this pictorial quality, this capacity to turn architecture into an experience, into a “spectacle of space”. I think, with Ungers, at a certain moment in his career, there is a deliberate decision to remove that component. I don’t think it is the same for Rossi, but other than some interesting drawings and a few good buildings, Rossi’s buildings are not only poorly built but also poorly designed; sometimes they are just a translation of his sketches into reality. Koolhaas tried to escape the extreme rigidity of the Ungers by using pop culture and creating a certain visual abundance. Although this aspect is not always very convincing, it recognizes that Unger’s approach was going into a dead end, where it was not even generating friction with the new tasks and had become an accumulation of the same thing over and over again. On that level, even though it is interesting that OMA’s work is dirtier, it is not an interesting thing per se.

SK: Do you associate the position that you have taken through your practice as a continuation of the postmodern discourse, or do these categorizations not concern you?

PPT: Well, it is unavoidable. It is post-modern to the extent that it is ‘post-modern’, and it is also post-post-modern. We are reacting to the world in which we live. But I don’t have a passion for postmodernism per se or for things like post-modern colour palettes or funny (or not so funny) anthropomorphic objects for the kitchen. My interest in Rossi or Stirling is more for their early period when they were critical of modernism, but they were still not post-modern. Generally, I am not so interested in pop culture, media, or media theory, even though I do not deny that we live in a society where pop culture and media have become very important.

SK: When you look at architecture as an intellectual discipline, does the richness of the intellectual side seem to be lost in the simplicity of the necessary actions?

PPT: I think the sophistication of one’s argument doesn’t need to turn into an incredibly complicated form of architecture. I sympathize with what you are saying, and I think reflective and intelligent architecture can be very simple.

On Realism

SK: Italy, in particular, has a long lineage of architects who address the question of realism, so what brought you to it?

PPT: There are many different types of realism. The first thing is that I’m interested in realism because I’m interested in reality. After all, there’s nothing else. I am unable to entertain myself with fantasies; I need to see “something”; I need to go to certain places; because on my own, I am a relatively boring person. So realism to me means to have curiosity for whatever is around me. I am not going into the specifics of “what kind of realism,” whether “socialist realism” or “neorealism,” but for me, it is important to react to what I see around the world every day.

Here, I think I am desperately Italian. Realism indeed has a very Italian tradition, from Machiavelli on. Even radicals in Italy were realists. The Italian communists were very happy to discover that Marx hated utopias, which made it possible to be revolutionary without having to believe in silly utopias. I completely subscribe to this; I find utopias to be unbelievably boring.

On Current Research Interests and Monumentality

SK: Could you talk about the things you have been thinking about at the moment and the future projects that you have been working on?

PPT: At TU Vienna, we are starting research titled “Wonders of the Modern World”. It is loosely based on the Entwurff einer historischen Architectur (Project of Historical Architecture) by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach. In his book, Fischer incorporated a lot of buildings, not only from a Western tradition but also from Turkey, Persia, and China. The buildings, or objects, that Fischer selected and surveyed have two characteristics. The first is that they are real; although they sound fantastic, they are not fantasies. In reality, all of these things existed at a certain moment—maybe not exactly how Fischer represents them—but they did exist. The second is that they are all very big, very monumental, and very exceptional. They are neither ideal things like utopias nor theoretical constructions like the primitive hut, nor are they functional buildings. They are only monuments—very big monuments. They are buildings that have very special and sometimes inexplicable reasons for being there.

We are trying to do the same exercise for the modern world (where “modern” is taken very practically as everything that came after the publication of Antoine Laugier’s essay on architecture, i.e., 1750). These buildings are still being built. It might sound surprising that “modern architecture” decided to ignore them, but there are still plenty of large, heavy, monumental buildings in production today. In search of such things, we visited Touba in Senegal for the Grand Magal, Batu Caves in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, and the church of Our Lady of Fatima in Portugal. We will be visiting Mount Rushmore in the summer, the Rio Carnival in February, and maybe after this, the Biswa Ijtema in Dhaka. We have a list of 60–70 places.

SK: Continuing from the previous point, there is an interest in monumentality in your thinking about architecture. Do you want to maybe say something about it? I think you described Niagara Falls as kind of a monument in On Bramante.

PPT: I am very interested in the relation of architecture to politics and power, and this collective dimension of architecture is particularly evident in huge buildings that cost a lot of money, require huge crowds to build, and so correspond to a certain desire for transformation or re-configuration of a certain society. As soon as practices become socially dominant in most societies, they are institutionalized by being turned into a building. These desires of a community are neither entirely known to the community nor the political leadership, bureaucracy, or architect; the building in the end is the sum of all of these efforts to define it. I find this extremely interesting—the most interesting thing associated with architecture.

SK: So one last question: what got you to On Bramante?

PPT: Generally, I am not interested in minor figures. Maybe it is because I come from a small city, maybe because I am a relatively simple person, but I am interested in the grand narrative, in things that matter and matter for many human beings. I am not interested in “forgotten heroes,” at least not in architecture.

Title: On Bramante

Author: Pier Paolo Tamburelli

ISBN-10: 0262543427

ISBN-13: 978-0262543422

Publisher: MIT Press (7 June 2022)

Language: English