Source: American museum and Gardens website

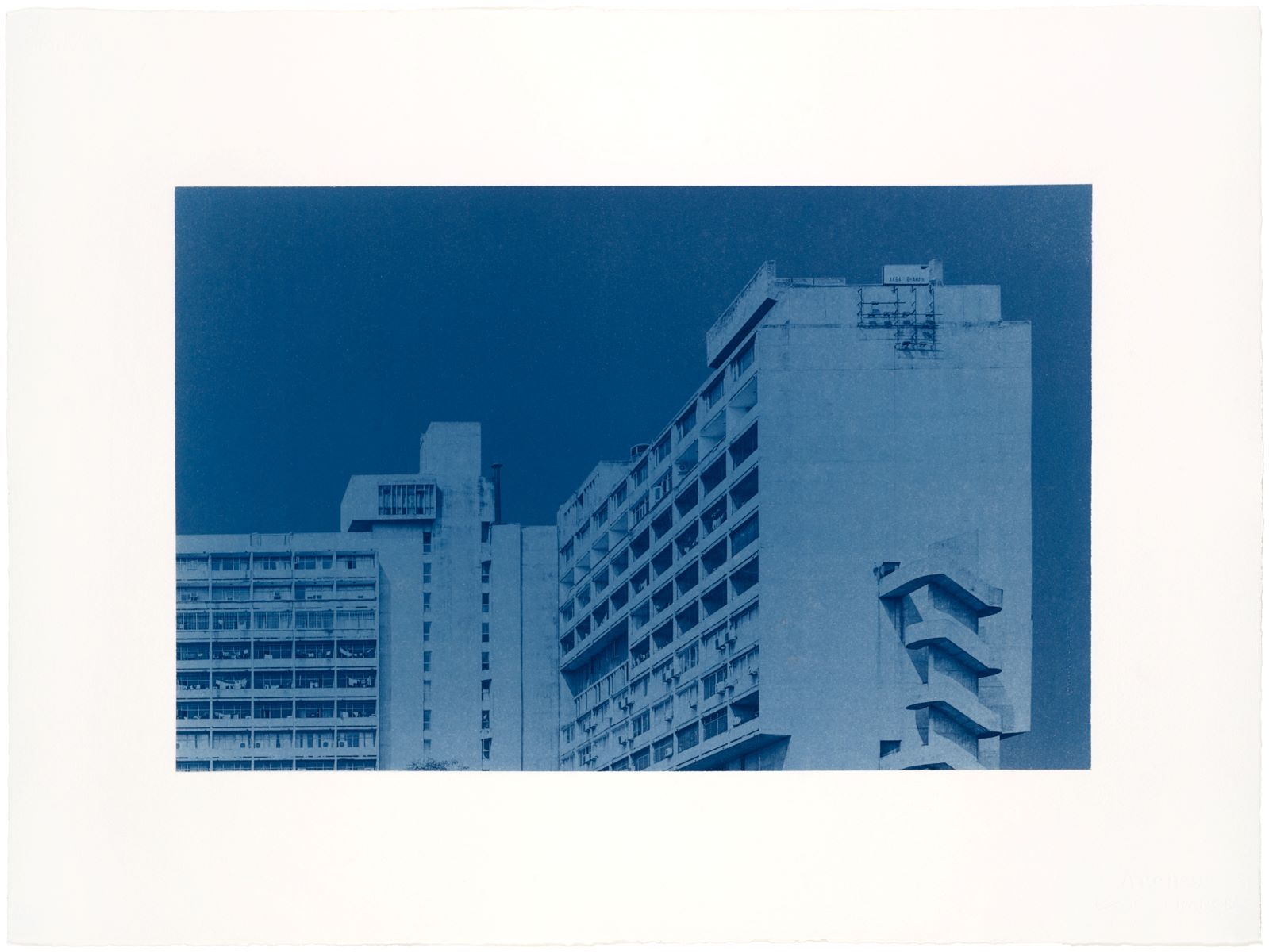

The cozily scaled city of Bath is one of the few cities in England which portrays Georgian architecture in its true glory. Yes, the city got her name ‘Bath’ from the famous 70th AD baths built by the Romans on the site of a natural spring. The picturesque and scenic location of this city, almost in a valley with steep-ish hills of the county of Somerset, England, is a favourite for travellers and architecture lovers. Bath, which is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, has painstakingly conserved her eighteenth-century architecture, thereby giving a euphoric peep into the culture prevalent then.

Even today in the twenty-first century, the city-residents live the past through minimal tempering with the urban planning and street art prevalent then, strict no material-change laws for facades, retaining the old-charm in interiors through furniture and finishes, emphasis on restoration rather than demolition of ailing structures and such other advice framed by the Council. A recent travel of mine to this city was rejuvenating, evoking desperate urges to see the process of conservation being pursued so meticulously in my heritage-rich country also.

of Bath. © Suneet Paul

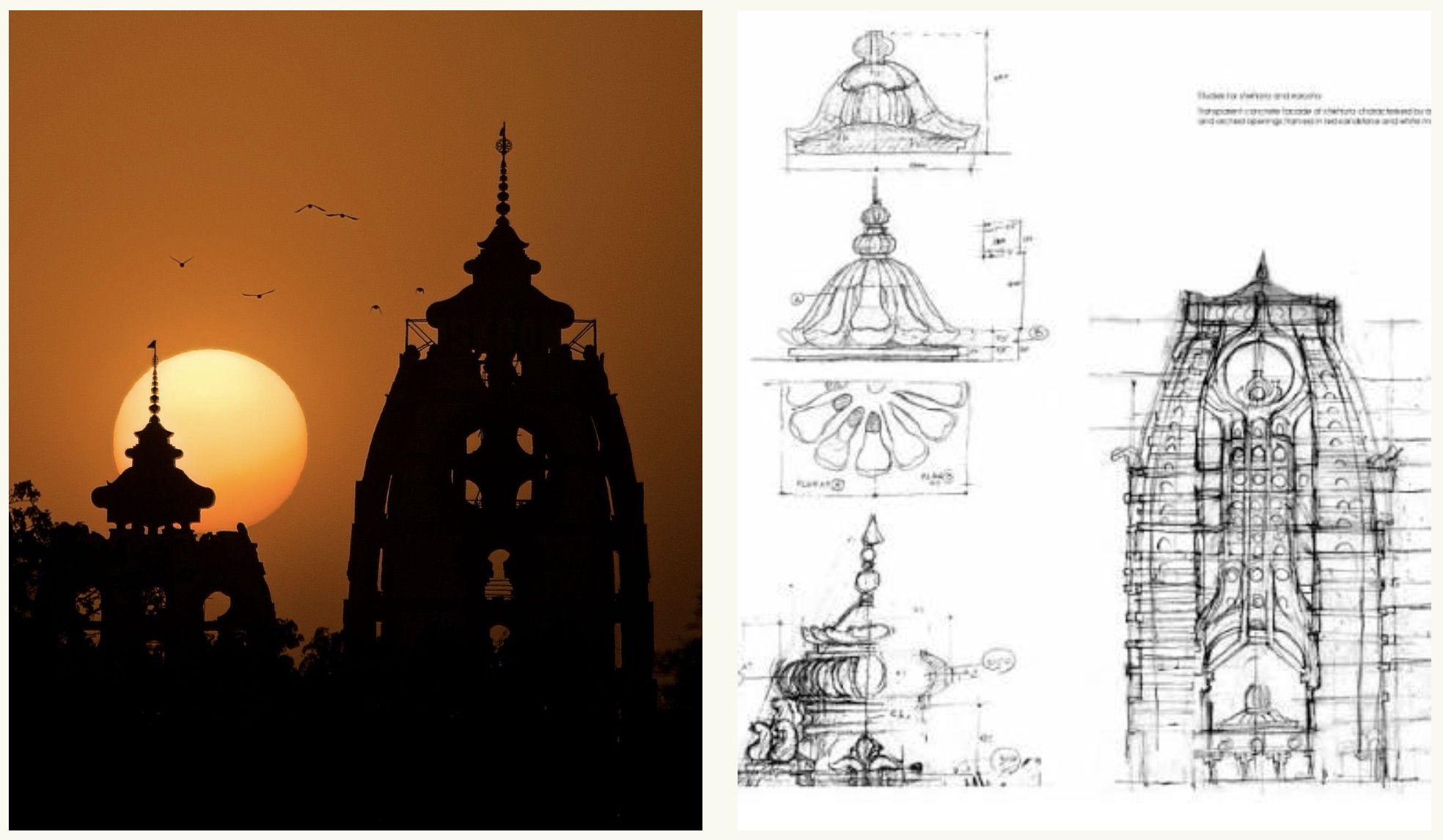

A closer and more researched glimpse of the past evolutions in history here can be well absorbed with a visit to the Holburne Art Museum and the Bath Architecture Museum. The city is abuzz with museums and treasure-trough institutions—the Herschel Museum of Astronomy, Museum of Bath at Work (showcasing the industrial eras), East Asian Art Museum, the American Museum and Gardens, multi-sensory Mary Shelley’s Museum of Frankenstein, Victoria Art Gallery, and such others. They are all immersive experiences in space and time with an emotive curation that provokes an enriched perspective. Someone mentioned that there are more museums in Bath in just one square mile than most larger cities can boast together.

A city with a population of around just one hundred and twenty-five thousand residents at one level appears to be frozen in history and yet has evolved with modern infrastructure in transportation, education and retail/commerce. Education is given priority in Bath, with two universities and several schools and colleges. The river Avon running through the heart of the city with a network of other canals is a defining feature, with crisscrossing bridges and walking trails along its picturesque banks.

Designed by Robert Adam in Palladian style, the restored Pulteney Bridge (1774) over this river is a tourist’s delight with a unique feature of having built-up shops on it. Talk about public transport and you’d find the buses and taxi services the most convenient. As we would agree, the best way to know a city is to walk through it. A stroll in Bath on her meandering cobbled roads unravels enthusing design and architectural highlights. Public squares with sit-out eateries and pubs add that carefree atmosphere to the slow-paced lifestyle of the city.

© Suneet Paul

Yes, the guided walking tour I took for some insights to the urbanity and architecture of the city was worth every penny. The restored Gothic-style Abbey Churchyard, built with a history spanning 1300 years, stands tall for its fine craftsmanship and monumental appeal. It is adapting for the future with innovative underfloor heating and a reduced carbon footprint.

The nearby Roman Baths, though not in use now, provide a glimpse of the then prevalent relaxed and luxurious environs when they were functional. Fascinating it is to view their preservation in four quarters—the Sacred Spring, the Roman Temple, an open-to-sky stepped bath hall and a museum. Our guide informed that there were quite many Spas in the city now to provide the nostalgic feel of the original baths.

Moving along, one gets captivated by the imagery of the thirty Royal Crescent terraced houses (1774). Designed by John Wood the Younger and built over a span of around eight years, this massive sweeping-curved building block is voiced to be one of the finest examples of Georgian architecture in England. The natural setting of this residential complex built in stone with large, well-landscaped lawns no doubt makes one pause and applaud the blend of nature and the man-made environs. Five minutes’ walk away from here, one encounters an equally grand ring of large townhouses, also known as the Circus. It’s no doubt a treat to view the classical order detailing, masterminded by the architect John Wood the Elder.

The unifying factor in the streetscape is the golden Bath stone used on the facades of the buildings. There are traffic restrictions within the city in order to prioritize pedestrians and cyclists, and promote use of sustainable transport. I gathered that the Bath Preservation Trust has laid down precise guidelines to adhere to, whether it be signage, advertisements, street furniture, lighting and illumination, street greens and plantations, colour palette, and textures or so many other such minute details that impart the urban character.

Bath today is a ‘wonder-city’ for the thousands of tourists from the globe that come here only because of the adherence of the laid-out Authority-guidelines by the city residents and the high-level of pride they have of contributing to retaining the ‘wow factor’ that the visitors experience. The locals no doubt enjoy a very spontaneous rapport with the abundant glory of nature.

This visit of mine to Bath, which was home to the famous literary icon Jane Austin and William Herschel, the discoverer of planet Uranus, further reinforced the belief that if the people’s will is strong, conservation and restoration can be very effective elements in aesthetically and purposefully protecting the cultural and design heritage of any country.

Architect/author Suneet Paul, based in Delhi and the former editor-in-chief of Architecture + Design, has to his credit a wide spectrum of writings and books.

One Response

Congratulations sir