The Architectures of Transition: Emergent Practices in South Asia is a three-year project that will examine the state of architecture in South Asia. This project will aim to ask collectively, across the region, the fundamental question: Does architecture matter in these states of transition? We believe this collective question and the subsequent reflections will not only resonate across countries in the region, but will be mutually productive, given the incredible common ground these countries share both historically and culturally. What does the practice of architecture in the region mean for the next generation? What does it hold for the making of the architect and architectural education? Can architecture address the abject inequity that surrounds us in South Asia at present? What does practice mean for women architects in South Asia?

While there are some recurring questions that are broad-ranging and defy political boundaries, there are also some physical implications and manifestations of architecture that are extremely local to South Asia.

So, what are the differences and similarities among the countries in the region? What are the new forms of patronage for architecture emerging across South Asia? How is architecture made relevant in circumstances within a region where uncertainty and unpredictability are pervasive? Oftentimes, architecture tends to gravitate towards absolute solutions and the question that then emerges is: How do we engage with the design of transitions? What is the agency of architecture while grappling with transitions? These and many such questions are what the project aims to discern and explore, while focusing on architecture in the public realm and on the question of the public agency of architecture.

There were many more pragmatic factors that led to the conceptualisation of this project and the associated lecture series. The first was the gap that exists in the discussion around architecture and urbanism across South Asia. This became clearer when, in 2022, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York held an exhibition titled The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 on South Asian architecture which extensively covered the early modernist period—or the period when a number of nations in the region had gained independence from colonial rule and were beginning to articulate their identities. It deliberately did not attempt to cover the period after 1985, thus underscoring the fact that there truly is very little documentation about the timeframe from around 1985 to the present.

Secondly, and on a more personal note, in 2016, with my colleagues Ranjit Hoskote and Kaiwan Mehta, we mounted an exhibition called The State of Architecture: Practices and Processes in India, held at the National Gallery of Modern Art in Mumbai. A two-day conference, one that focused on South Asia, rounded off the exhibition. The conference brought together architects from all the countries in the region including Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, and Pakistan. The common issues, struggles, and emergent conditions across these nations became increasingly vivid, triggering off incredibly productive discussions and infusing a collective motivation to consider extending this project. Interestingly, the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute at Harvard University (LMSAI) was one of the supporters for this conference and so it is rather appropriate that we are now, with their renewed support, extending these conversations in the form of the current project.

The Architectures of Transition has six major components: A lectures series, publications, a conference, a travelling exhibition, podcasts, and a digital archive to capture the ongoing research.

The project is cognisant of the fact that some discussions about architecture and the different modes of engagement in practice are most productive within a generation while others are more productive across generations of practitioners. Thus, some components—such as the lecture series—are structured to create intra-generational conversations while others—like the conference, podcasts, publications, and the events that will surround the travelling exhibition—will be designed to foster inter-generational conversations. While these forms of categorisation cannot be absolute or complete, we hope they will contribute towards contextualising the issues within a temporal scale that is productive for the participants in the research.

The lecture series is conceived as having three components to facilitate both inter and intra-generational conversations among students, practitioners, and academics in South Asia, organised over three years. The first (the focus of this book) is titled Emergent Architectural Practices in South Asia. Its intent is to create a platform for emerging practices to articulate their position as well as expand their network of peers to collectively push the intellectual boundaries of the field. The second, titled Reflecting on Architectural Practices in South Asia, will involve practitioners who have been in the field for over four decades and are well situated to reflect on their trajectories. Here, the intent is to present and archive shifting issues as well as engage with what these practices have experienced over the decades. It is hoped that these engagements will not only be helpful for younger practitioners but will also facilitate research and a broader theoretical discourse about practice in South Asia. The last component is titled Interrogating Models of Practice in South Asia, the aim of which is to create a platform for architects who have been practising for at least a decade or two, currently in mid-career positions. Through this component, it is envisioned to have practitioners articulate their ongoing and often active praxes to situate their work within the diverse modes and models of practices emerging in South Asia.

Currently, in South Asia, there are very few platforms for discussion among practitioners from the region. To understand the pluralism of modes of practices requires much greater interchange than we see at present.

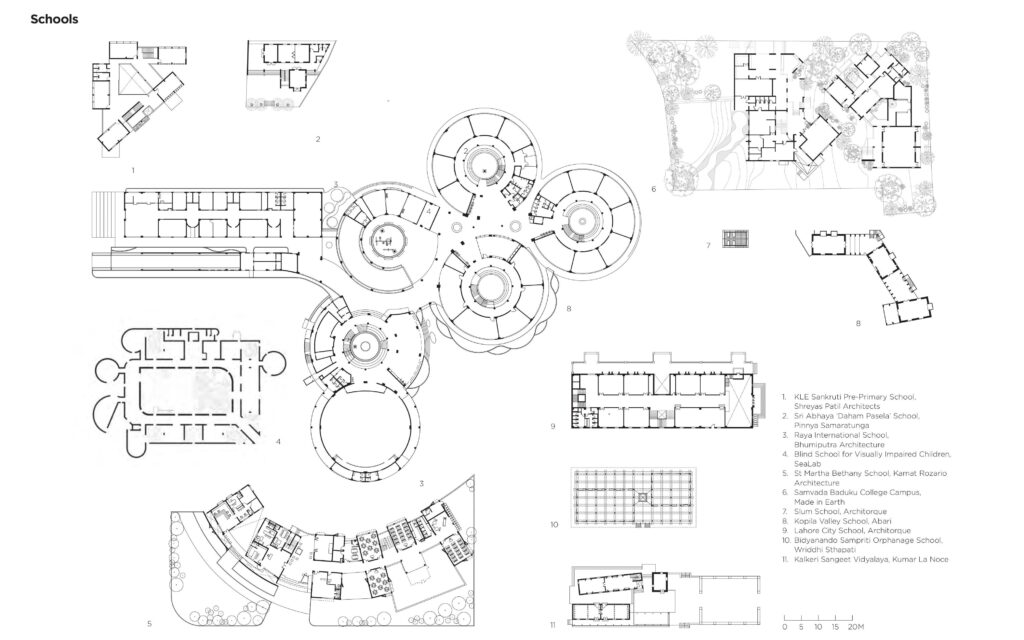

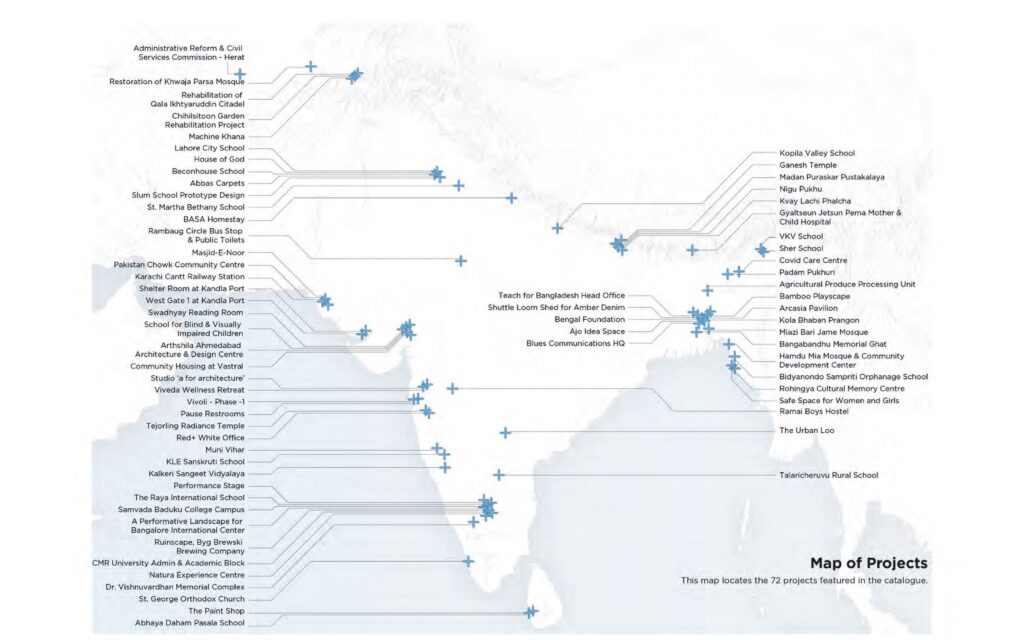

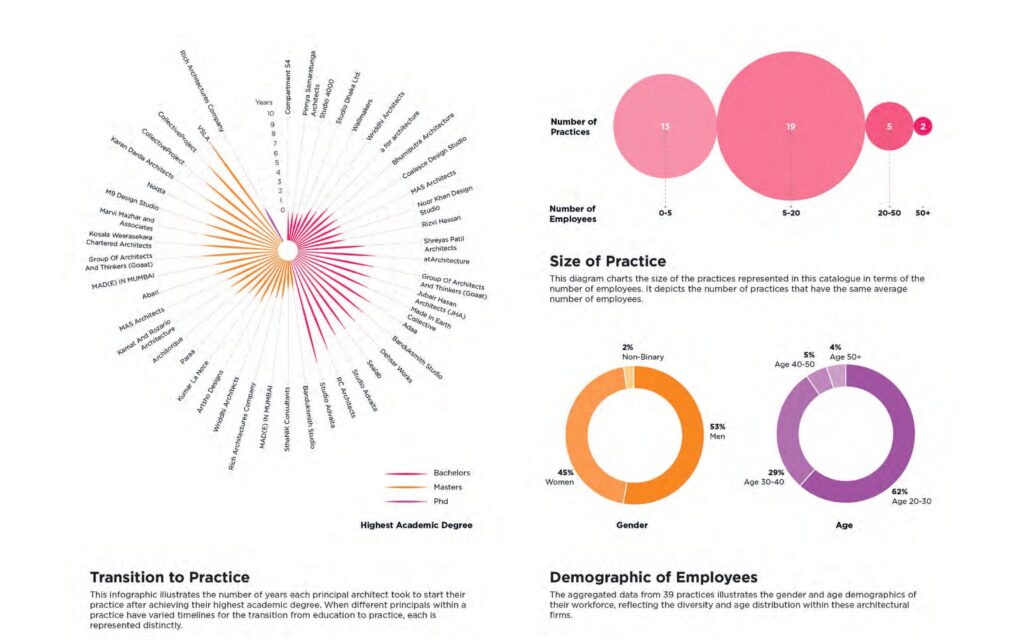

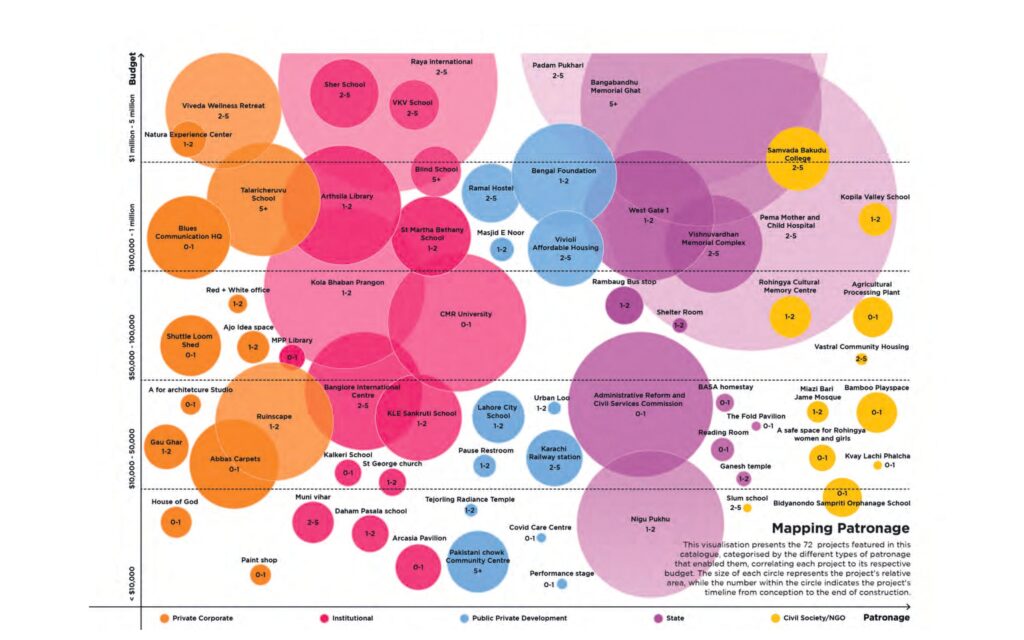

The lecture series and this publication will serve as instruments to read the pulse on the ground in the region. Both these components focus on young practitioners and aim to better understand not just the opportunities present but also the issues that current and emerging practitioners are grappling with. Furthermore, this is an endeavour to create a comprehensive survey of the South Asian architectural landscape that helps gain insights on forms of patronage, methodologies, emergent technologies, and construction techniques. It also sheds light on how the humane and social aspects of architecture—characterised by participatory frameworks—are being approached by practitioners today. By focusing primarily on the architectures of transition, we commit to the validity of modes of engagement as well as transgressions and synergies between disparate cultures, ways of representation, and knowledge accumulation and production. Thus, this publication is an attempt to cull from the lecture series and extend the research to identify additional practitioners—a total of 41 to represent this new emerging landscape of practice in South Asia. Included in the publication are reflections from practitioners in the region along with a framing essay to contextualise these practices. Additionally, there is a graphic taxonomy of plans and types most prevalent as commissions emblematic of the public agency of architecture among younger practitioners. Lastly, infographics from a small sample of 41 practitioners— but one that is representative of the spectrum of practices in a broad regional spread—is an interesting read.

The hope is that the ecology of practitioners and network of peers created through both, this book and the lecture series, might lead to cross-pollination of concepts and methodologies in addition to critique and reflection among the next generation of practitioners in the region.

Of the 41 practices included in this publication, a total of 12 events covering 24 practices were curated as part of the first component of the lecture series, Emergent Architectural Practices in South Asia. This took place from February 2022 to March 2023. These lectures and subsequent conversations were recorded and made available online as an element of the ongoing digital archive. The publication will also be extended into a travelling exhibition.

Like any project, there are some obvious shortcomings which we hope we can compensate for and rectify as we traverse the remaining components of this multiyear endeavour. There are clearly some omissions and imbalances. For example, in this publication, the Maldives is absent, as it was a challenge conducting research to identify young practices in the country. Similarly, while we had more participation from Bhutan in the lecture series, it was difficult to collect that material for the publication on account of the differing ways of archiving and communication. While we could include three practitioners from Afghanistan, we made an exception and included two architects who work in larger organisations as the private practitioner has more or less ceased to exist, given the political situation. We also tried to have a substantial representation of women-led practices from each country to attain a gender balance in the curation. Nevertheless, owing to the specific age group we focused on (below 40 years), identifying as many women-led practices as we initially hoped for proved challenging. We have learnt from these shortcomings and will address them going forward. As we expand and re-formulate the next stages of the project, much needs to be done to fine-tune our questions.

What might encompass architecture as a profession, and how can we expand this to go beyond the material composition of place?

This project would not be possible without the help, support, and time donated by the practices included in this publication. These architects connected from wherever they were located—many at remote sites and some from the comfort of their studios. While some of the practices included in this publication participated in the lecture series, some were identified later as part of the extended research. All in all, their contribution has been tremendous, for which we are most grateful. We acknowledge that there are many extremely talented young architects we have failed to identify and include here. Then there were some who were unable to get us the material in a timely fashion or had constraints that restricted them from sending their projects for inclusion. This is our loss. Our hope, however, is that this publication will eventually accompany an exhibition that will travel, and through local curators will add more material and talent.

An undertaking such as this is the work of several individuals and organisations, so thanks are due to many. This project would not have been possible without the help of the Lakshmi Mittal and Family South Asia Institute (LMSAI), and we would particularly like to thank the executive director Hitesh Hathi for his consistent support since the very beginning. Similarly, we would like to extend our gratitude to Selmon Rafey (programme manager) and Carlin Carr (assistant director) from the LMSAI for setting up the virtual platform for the discussions as well as getting the word around—both critical to the formation of a robust community. We would also like to thank Martino Stierli, The Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design at the MoMA in New York, who generously collaborated to set up an event at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) to celebrate the then ongoing exhibition, The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985. The event, titled Conservation in a Shifting Landscape: The Future of Modern Architecture in South Asia, was held in March 2022. More importantly, the discussion was also the platform that launched The Architectures of Transition. We are also grateful to Kathleen James-Chakraborty, professor of Art History at University College Dublin and Eve Blau, professor of History and Theory of Urban Form and Design at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design who participated in the conference.

Since the inception of the project, we have had advisors who have shepherded it by sharing their insights about the region and the countries they live in. This assistance and advice have been invaluable in formulating not only the components of the project but identifying architects in South Asia who otherwise would go below the radar. Our sincere thanks to Ajmal Maiwandi (Afghanistan), Fuad Hassan Mallick (Bangladesh), Rajnikant Chavda (Bhutan), Kaiwan Mehta (India), Ranjit Hoskote (India), Chitra Vishwanath (India), Sanjeev Vidyarthi (India), Biresh Shah (Nepal), Yawar Jilani (Pakistan), and C. Anjalendran (Sri Lanka).

The South Asia GSD Student Group at Harvard GSD—who were integral collaborators in formulating this project—had varying contributions at different periods of the project. We are grateful to Aeshna Prasad for being there from the early stages, and continues to connect as often as she can, and to Dhruv Mehta for driving the conference component through its early formulation. Gratitude to Rolando Girodengo for leading the graphics for the lecture series and helping us evolve an effective outreach. And to Pia Kochar, Amna Pervaiz, and several other students who stepped in when we needed their help. My thanks to our institutional partner, the Architecture Foundation India (AF) in Mumbai, who have also been of immense support for research as well as the preparation of drawings for this publication. Many thanks to Ela Singhal, executive director of the AF, and Anushka Kulkarni and Sriparna Seal for their continuing support. We would also like to thank our copy editor Khorshed Deboo for her keen observation and meticulous editing. All their contributions go beyond this book to the larger project of The Architectures of Transition. Our heartfelt thanks to Altrim Publishers, and particularly Ariadna A. Garreta who bet on us, and to designer Núria Sordé Orpinell who skillfully synthesised the disparate material into a visual delight! Our thanks also to the sponsors JSW Foundation and Kanika Pruthi for their consistent support towards the many components of the project and for facilitating the realisation of this book. As we move into the next stages of the project, we will count on the support of many more and look forward to learning from those interactions. Thank you all.

Lastly, my acknowledgments go to my co-authors on this publication and champions of the project at large—Devashree Shah and Pranav Thole—who have spent enormous amounts of time, patience, and their fine judgment in putting this book together. This first deliverable in a broad and ambitious project was critical in giving us both direction and confidence. Their contribution is a gift to the profession in South Asia. And finally, this project is dedicated to all the architecture practitioners in South Asia, especially to the generation that is starting out on their trajectory in the profession—that is to make the built landscape of South Asia through imagining architecture that will be sustainable, humane, and pleasurable for the population inhabiting this region.