The book review is a part of VK:a Architecture’s initiative ‘Annual Book Review Awards’, where VK:a team is encouraged to review any book of their choice.

Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi, better known as B V Doshi, was loved and respected for his contributions to the field of architecture even before he became the first Indian to be honoured with the prestigious Pritzker Award. Doshi’s designs are renowned for belonging to the people and to the place. But his legacy goes beyond his buildings. Doshi was an educator who inspired the next generation of architects with his thoughts and teachings. He was also an excellent storyteller, proven by his autobiography, “Paths Uncharted.”

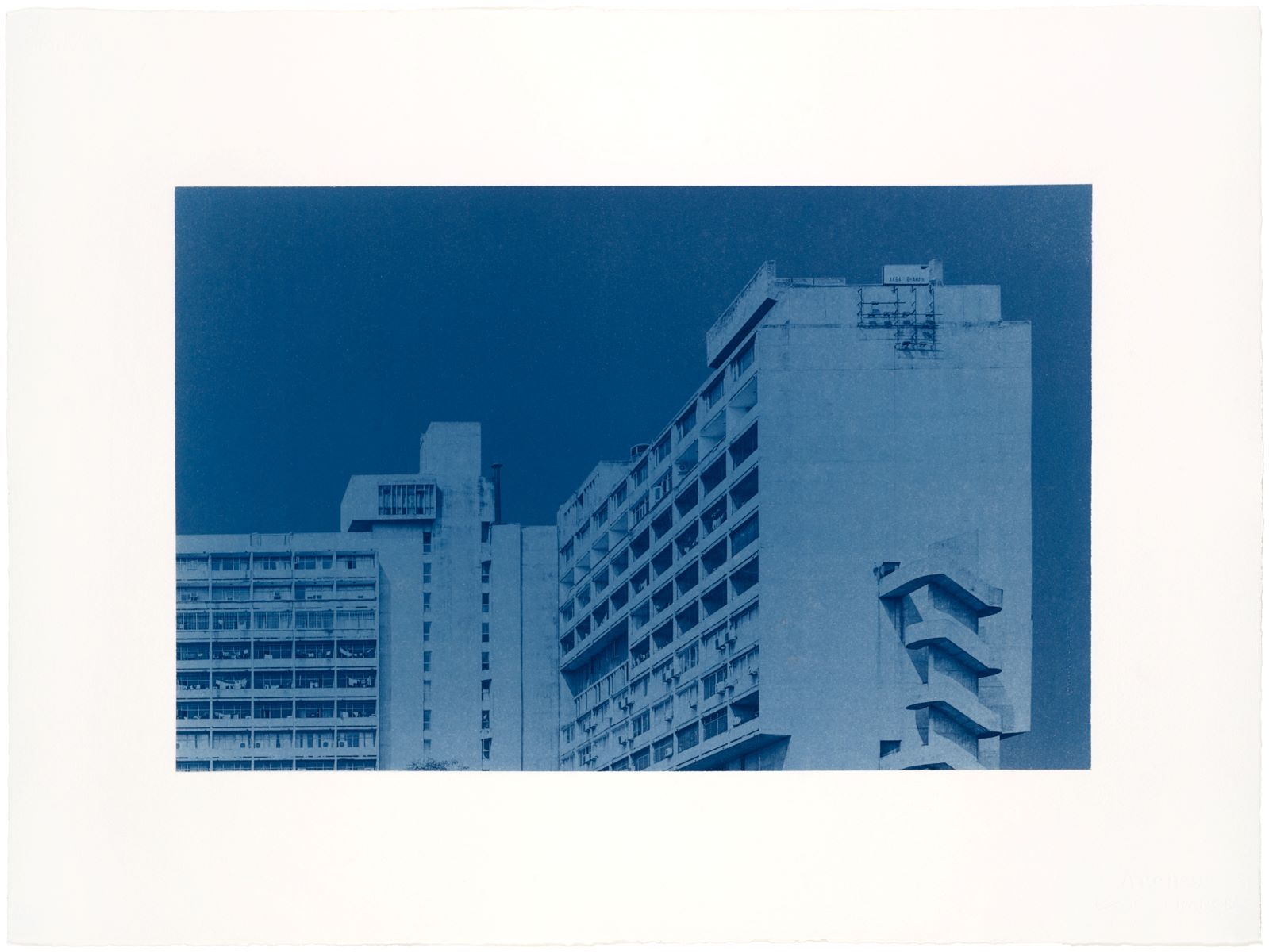

As the world mourned his passing earlier this year, a sense of guilt that arose from the realisation that I barely knew anything about the beloved architect (despite spending months toiling in one of his best works – the CEPT campus), pushed me to pick up the book.

What I found was not the gloat of a master architect, but a humble honest man, as surprised as I am, to find himself amidst a series of fortunate events.

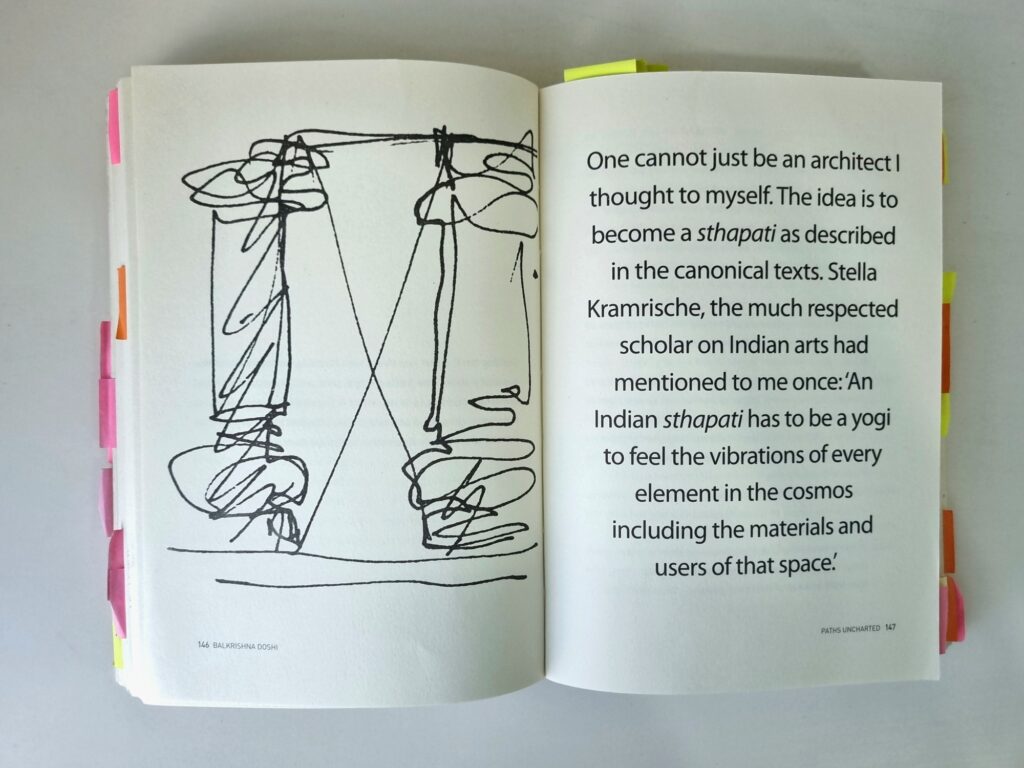

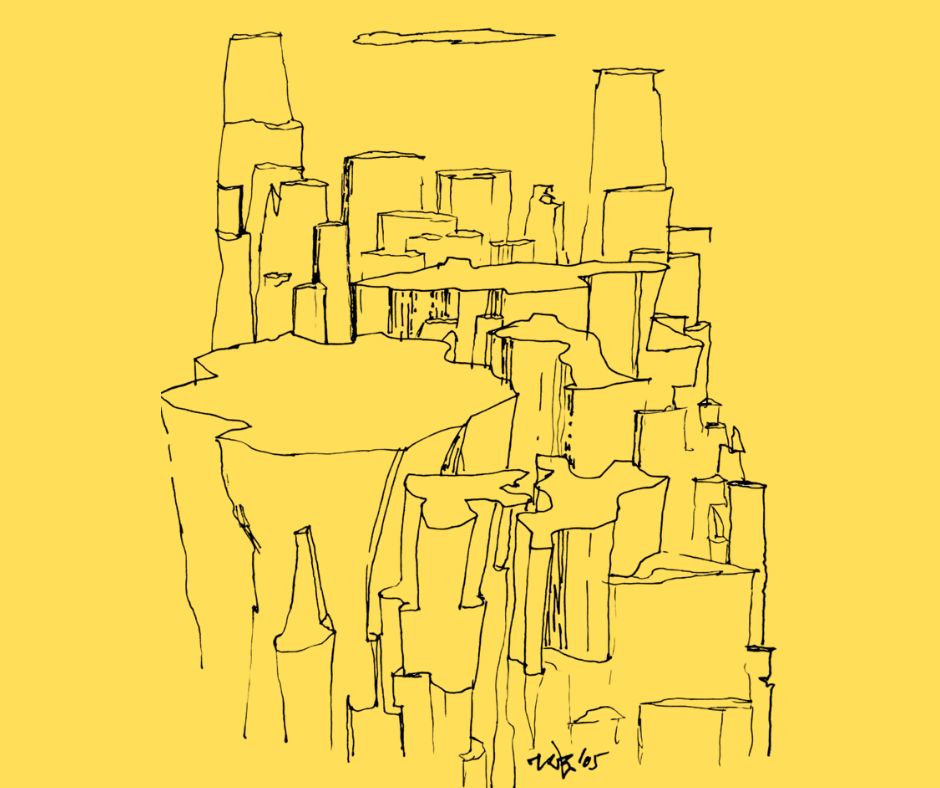

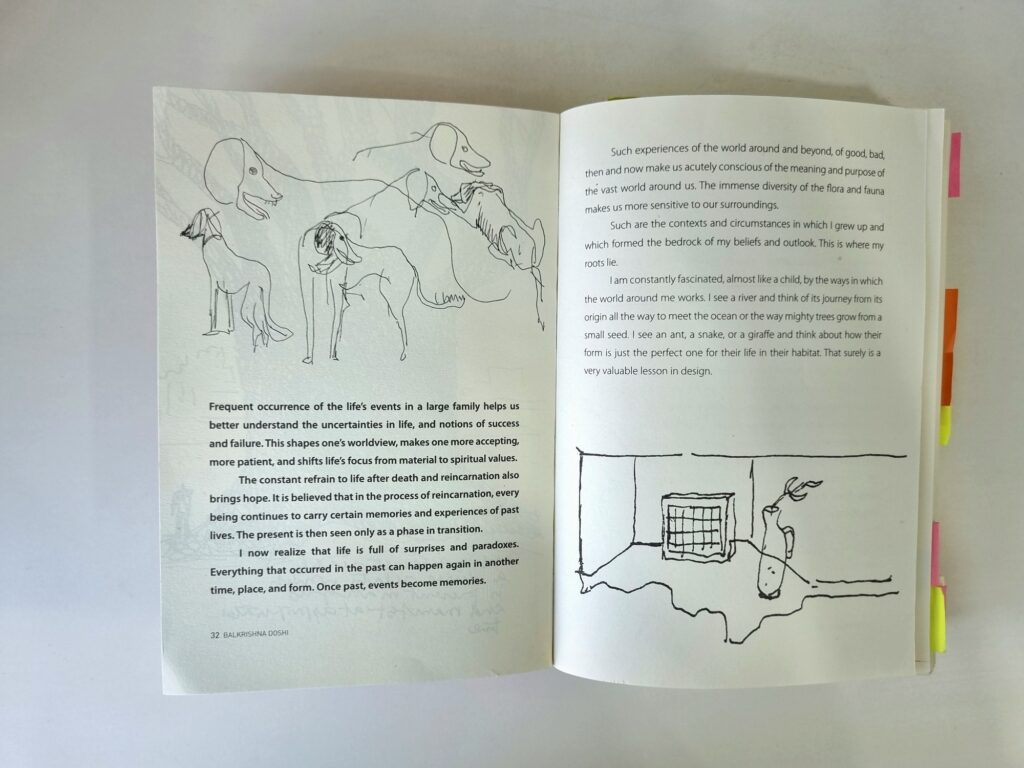

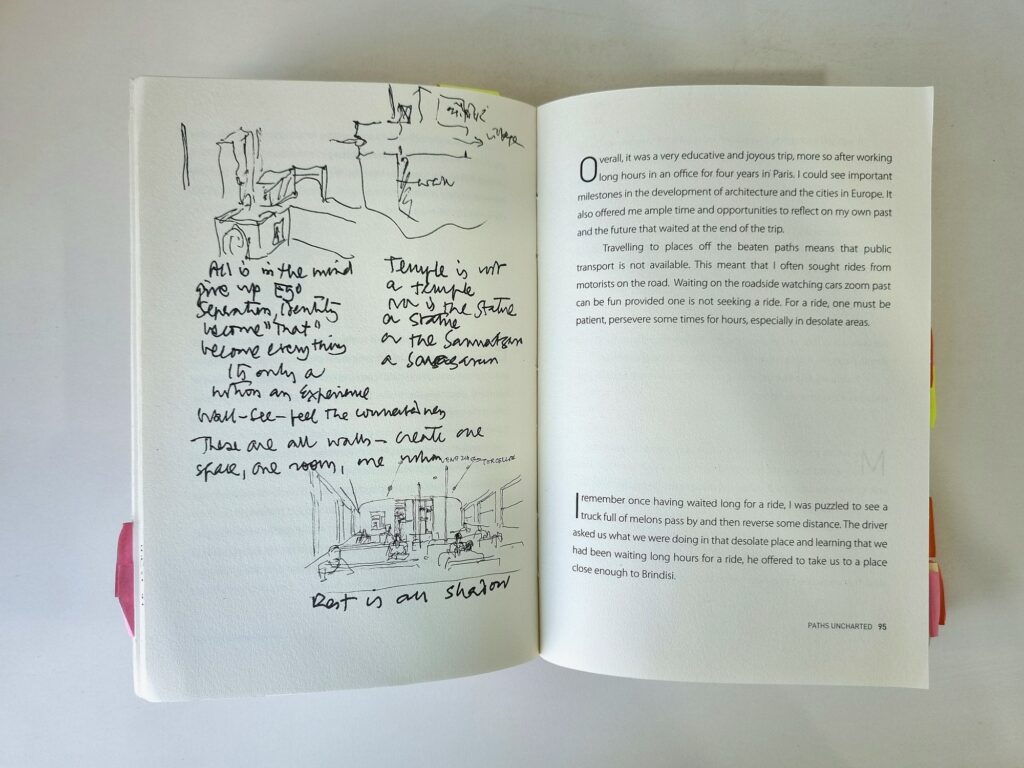

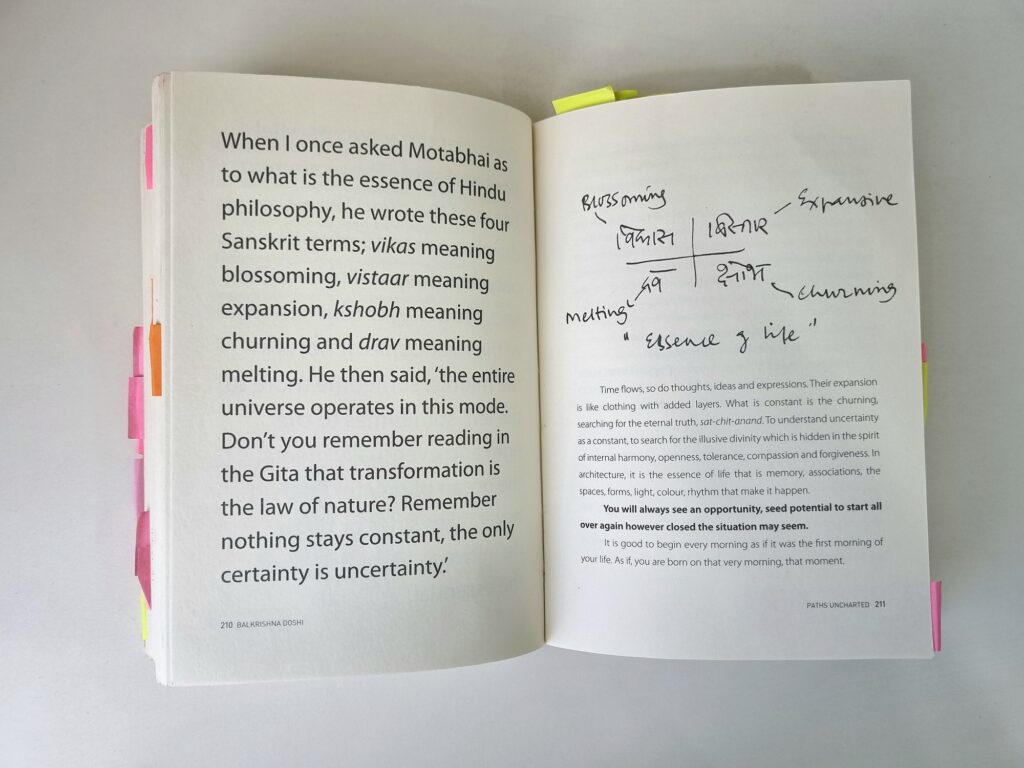

Collated from his meticulous notes, diaries and audio tapes, the book immediately appealed me with the bolding of important concepts, changes in font text to highlight the event and interspersed hand-drawn sketches and doodles. The format of the book convinced me that B V Doshi has an in-depth understanding of not just architecture, but also of architects, most of whom are not voracious readers.

He prefaces the book by saying “These notes are links to my straying and uncharted life. I feel interconnected randomly. Yet I see a thread, a sequence through all these events as if it contained a purpose.” With this warning, he takes the reader along into his Pensieve, jumping from one memory to another – his chance encounters with some of the most remarkable people in his own and allied fields, and equally extraordinary patrons; the stories of his childhood in their ancestral home; moving to London and then to Paris to work with Le Corbusier on nothing but intuition; the events that led to meeting the love of his life and settling in Ahmedabad; a rare insight into his personal beliefs in mythology and spirituality.

The non-linear recounting almost makes one feel as if he is sitting in front of you, narrating pieces of his life as he is remembering them.

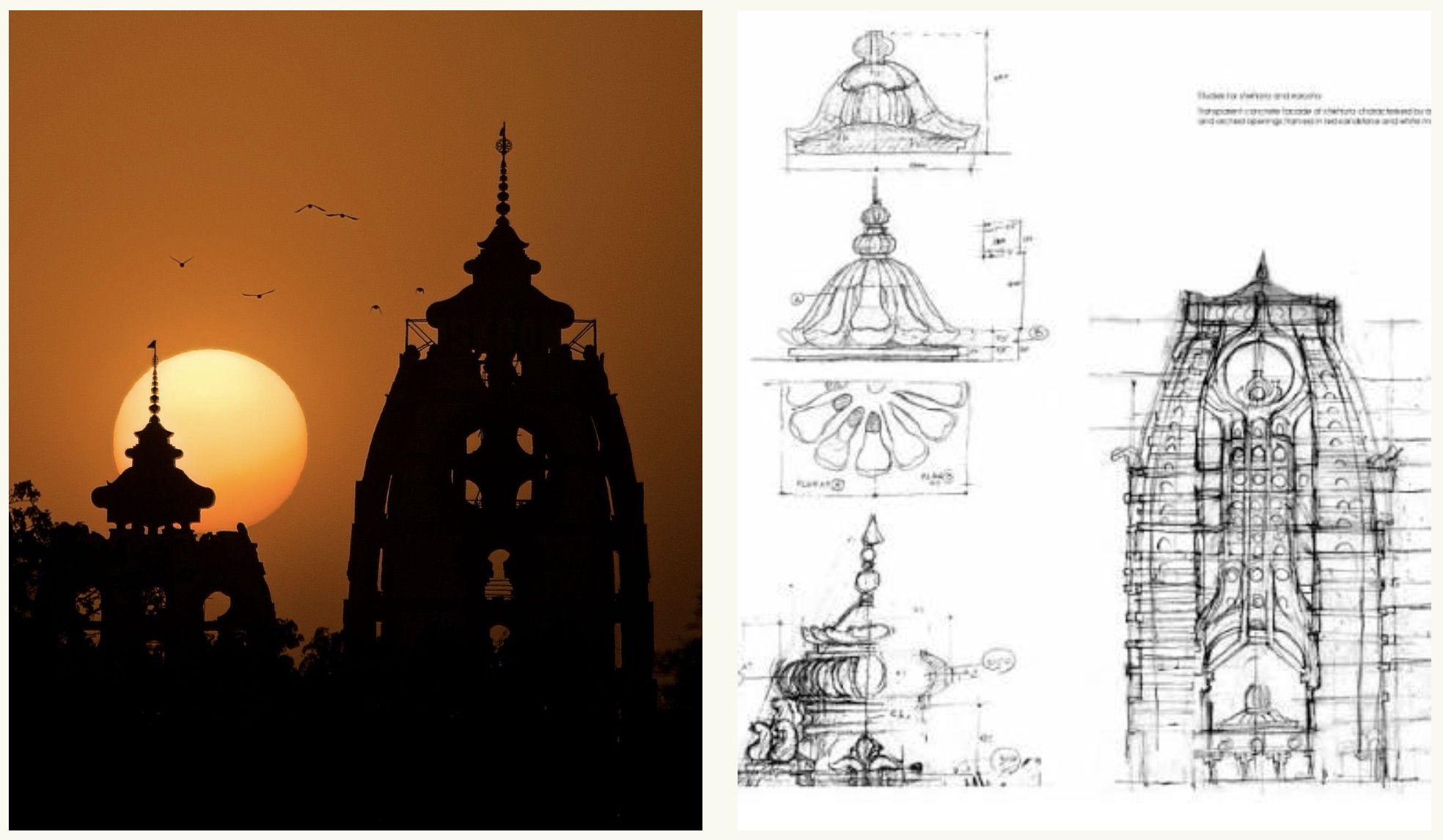

I am convinced that B. V. Doshi’s sensitivity to site conditions arose from his exposure to the varied landscapes, materials, technologies and lifestyles during his travels across countries and continents. Beyond his work in London and Paris, he hitchhiked all over Europe before coming back to India. In Italy, he examined the plan of Rome drawn in the 17th century by Piranesi. In Venice, he was awed by the canal, foot-bridges and people friendly open spaces. “Until I went there, I had not realized the wonder of not having any steps or level difference between water and the floor, that was the norm in India.” During his visit to the Acropolis, he couldn’t help drawing parallels between the temple sites in India, “physically isolated to make it difficult to reach yet visible enough to attract the devout.” His design for the Matar shrine in Gujarat was an attempt to recreate the experience he had in the Pantheon. “Though it appeared insignificant at first from the street, once inside its interiors stunned me. Its scale proportions, volume and especially the light cast by the oculus in done made it a divine experience,” he recalls.

Every place he visited was a place of discovery, both of the self and those embodied in that space. He learnt about societal issues, politics and way of living of different sections of society, especially the poorer segments. Everywhere he went, he was constantly reminded of the economics in architecture: “making most of the resources… from the choice of building materials to appropriate construction techniques, emphasis on multiple use of spaces have been important concerns all my life.”

The exploration of narrative is something that interests me as an architectural writer. Including a story in a building creates a level of meaning and connection to the patron or user that can be engaging and provoking.

Not only did Doshi’s structures weave stories, he created stories to substantiate his structures. He was inspired from the tales and epics he used to listen in his childhood from Dada and other elders. The story of God’s first avatar being kurma, the tortoise became the story of the unusual form and ground relationship of the Amdavad Ni Gufa.

When Doshi was asked to design the NIFT campus at Delhi, India was carving its niche in the global fashion industry. He conceptualized the campus around a central kund, a water tank usually found near temple, which became the connecting element of the otherwise scattered structures. To explain his proposal, he wrote a story as that there was an entire village around a sacred water tank with mysterious healing properties, dilapidated and forgotten under modern developments till NIFT happened. His wry sense of humor also surfaces in the anecdote of some Board of Directors members who, believing the story to be real, inquired about selling this ‘sacred water’!

“I live in paradoxes. As a result, there is a constant struggle to confine, to find security, to create walls around and then try to open them with windows and doors to see outside or to go out. The choice I make is to be in and out at the same time.”

Putting forth the plethora of events and paradoxes that inspired him – Corbusier’s boldness to break free from rules vs. Kahn’s meditative precision to geometry and adherence to simplicity; Western cities’ order, technology driven aesthetics and mobility vs. the chaos and organic growth of Indian cities; the scientific temperament of Modernism vs. the spirituality, myths and Hindu philosophies he imbibed from his childhood – without imposing any conclusive philosophies for his life or architecture, he urges every reader to chart their own path like no other.

Guided by nothing but the courage to ask questions, the grit to find answers and the belief in a larger scheme of things, he turned out to be a just another person, like you and me. Yet, he was not. What led him greatness? His willingness to take risks, to take uncharted paths without knowing exactly where it led, but still, following it through till the end, giving his all in the processes. He had an ultimate aim: to be a good sthapati, and he was willing to work harder and longer to achieve it.

The book is a glimpse into the mind of a man striving for perfection with the fascination of a child.