Transcript of the Audio

(If you find errors, please leave the comment in the comment box)

Ashish Ganju

You see, it starts actually with getting any architectural work. When you look at the problem, the architectural problem. You know, conventionally speaking, you have a site and you have a program. When you put the two things together, then you get architecture. You have to have a site and you have to have a program, this is a conventional view. Today, people might say, because of artificial intelligence, you can do away with the site and the program, but I’m not going into that area at all. So even now, the issue is, site and program and to program actually works based on certain values, you have to discover what are the values, which suit that particular situation, which means once again, that you have to look at the symbols, which will reciprocate or which will mirror life around you. You can convert a symbol into an architectural proposal, but you can’t construct, you can’t convert a value into an architectural proposal, a value is a generalized understanding of life.

(But) If you can reduce your values, or transform your values, or describe your values, in terms of certain symbols, those symbols can certainly be transformed into built reality, at some point or other.

Now it is that work, which I’m trying to do, mostly, what we’re concentrating on is how to convert our understanding of life into a set of symbols, values into symbols. You understand life through values and be converted into symbols, which symbols can then be built. This is the transition, this is the sequence of thought.

And yes, how you represent symbols is another, or how you represent values is another issue.

(Because) Architects are not used to being to representing values, this is the problem that I’m facing. I’m saying that how do I represent the work that I’m doing here, man, as a, as a presentation, to a set of fellow architects. Because, mostly architects are still confined in their thinking…

To what Verendra was talking about, objects, and you only can describe or represent objects. That we can do very well. As you know, I mean, some of the leading architects in the world are so expert and including all the stars in the west, you know, why we built this, BIG (Bjarke-Ingles) people and all. I mean, they are just good at that, you know? But, my concern really is that there are human values, which govern our lives. And which relate us to other people, which relate us to society, so those are very valuable.

And those values, we have to actually find representation for them as symbols. because symbols can be communicated through built reality. The built reality that you see is actually extremely symbolic.

The best architecture is the one which has symbolic value. Symbolic worth. Let’s call it that. And the best of it is the one that uses archetypes.

Archetypes are symbols, which are buried in our unconscious. The unconscious is the deepest part of our mind. Those archetypes buried in our unconscious, actually link us with all humanity, because the archetypes are what is shared by other people, by everyone.

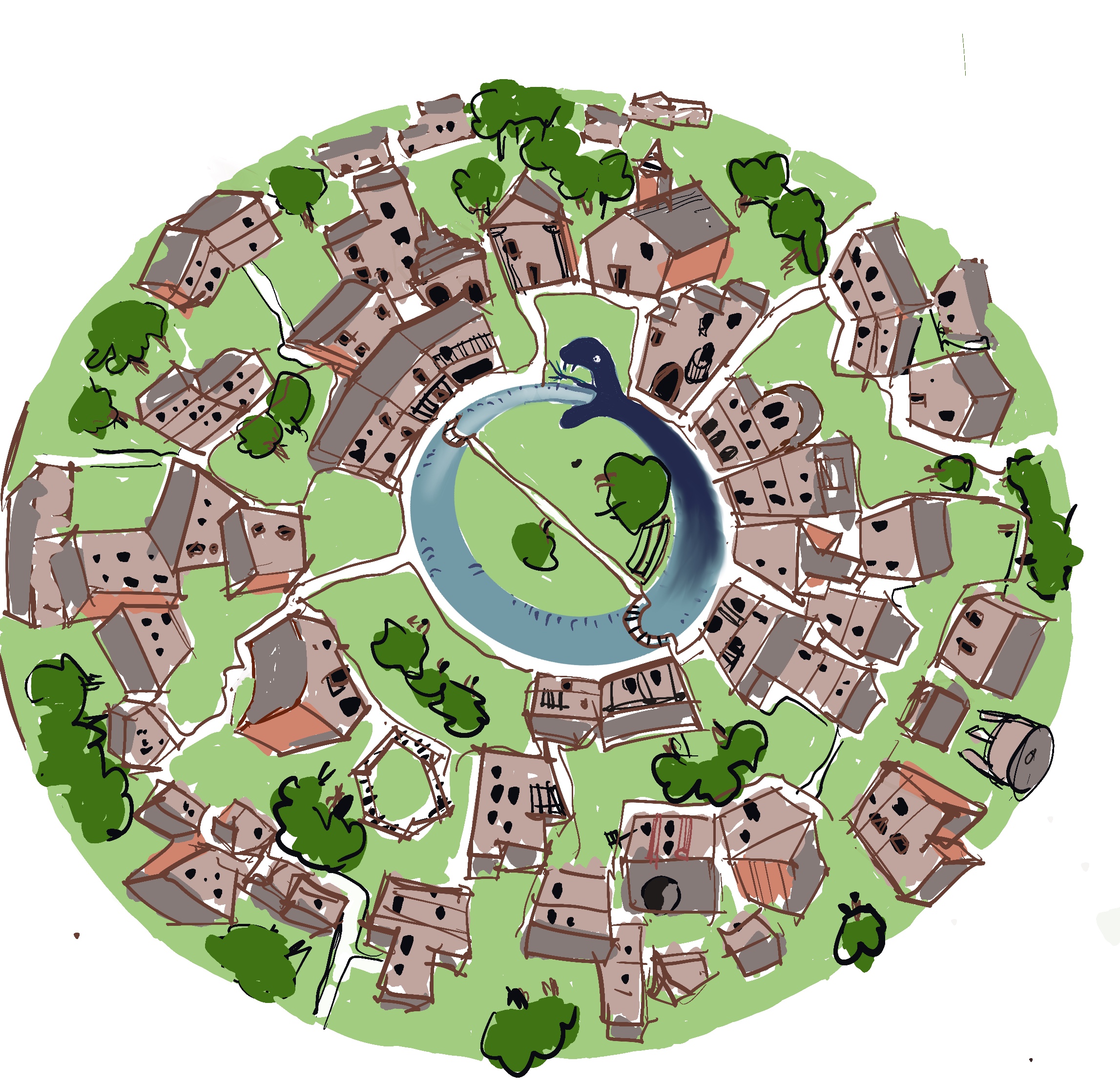

I mean, this Swiss psychologist, Carl Jung has written extensively, we all know well, about that. And the whole notion of archetypes, and how archetypes actually connect us through our unconscious with other people. Jung talks about a collective unconscious, even a racial unconscious, that an entire race will share certain archetypes in its unconscious, but they are unconscious states. To bring them to the conscious level, you have to actually find symbols, you have, for instance, that Mandala, which is the GREHA logo now, which was the design for the Museum of Tantra, that one that was devised. I mean, I in fact, took to Jung’s writing because I saw a book when I did that design, Ajit Mookerji had asked me to do it. Ajit Mookerji was at that time, the Director of the National Crafts Museum. And I remember going to his office, it used to be in Thapar House, in Janpath Lane. And in his library there, I saw the book, Man and His Symbols, by C.J. Jung. And, I borrowed it actually from him, and I went through it. And it’s very fascinating for me, but Jung had done a lot of research into this, in Switzerland with his clients, with his patients, about man’s this kind of symbols that we have in our unconscious mind, and how those if he can reach out to those symbols and understand them, how they actually help in the process of healing, especially for people who have got, you know, distorted mental conditions.

So, to me, the idea of an archetype is very important, and it still is, that we actually must locate the archetype, which then gives us an understanding of the symbols, which will fit a particular site, which will be suitable for design. So it’s a progression, going from what you see around you, right down into your unconscious, which you cannot see, which is an, in fact, the ability to communicate with the deeper recesses of your mind is what meditation is about. So, you know, you have to actually, therefore, find the doors to your unconscious, somehow. Once you can begin to find those, then you begin to actually also come up with archetypes.

Right now, looking back on my work, I find most of it is actually archetypal. The diagrams if you look at their very archetype. And I think that is what is the if anything, that is the strength of those designs, in some not in all, but quite a lot of them. The SOS village is very archetypal.

Verendra Wakhloo

Which is of course born out of the mother and childcare.

Ashish Ganju

Kind of, it’s born out of my experience in the rural area. And the work that I did for the government and UNICEF in the rural areas. Actually my studies it’s not really ‘work’ because I didn’t work, but I was studying Indian architecture in India, at the grassroots, in the rural areas. And I remember writing to English friends of mine from my college, from that time, There was one very good English friend, he was the best designer in the class. And I remember him writing back to me saying that it’s the same for us here, by looking at work in rural areas, we learn about the techniques, the way architecture is. So, the origins actually come from there.

Verendra Wakhloo

It’s like real languages.

Ashish Ganju

Yes.

Verendra Wakhloo

Sanskrit is born out of, probably, out of many informal languages,

Ashish Ganju

Well, they say that Sanskrit is the summation of all the vernacular languages.

Verendra Wakhloo

Because the other way can’t happen. This is just improbable, no? That, the formal language is before the vernacular, it is not possible.

Ashish Ganju

The formal can never precede the vernacular, the informal. The informal, the spontaneous, is what links us to our humanity. it’s what links us to the whole of everything around us. So to reach out, you see, my work is now really largely with the informal. I mean, if you put it in conventional terms, I keep working with the informal sector. This is where my work is now. And the informal, in fact, don’t use the term I hate to use the term ‘informal’, I call it spontaneous. This is what I call spontaneous development. And in fact, I would be rather primitive. I also am trying to reach out to what is spontaneous architecture.