According to folklore, beneath the ground in Bhuj, in the Kutch district of western India’s Gujarat, lives a snake. Long ago, when the king wanted to settle the land and build his kingdom, he was told that he would have to thrust a nail into the ground and spear the snake through its head to make the earth stable. The king did so, but, curious and unsure of himself, he quickly removed the nail to evaluate his aim. The snake survived and, according to the legend, it now lives beneath the ground, shaking the earth when it moves and causing quakes across the region¹ This is why whenever a new building is inaugurated in Kutch, the first ritual is to drive a nail in the ground to stabilise the building.

On 26 January, 2001, during a crisp winter morning in Kutch, the earth started to violently shake. In a span of 22 seconds, an earthquake with the magnitude of 7.7 rippled across the city, causing around 18,000 people to lose their lives. Those 22 seconds remain etched deeply in the minds of the people of Kutch – and today, everyone has an earthquake story to tell.

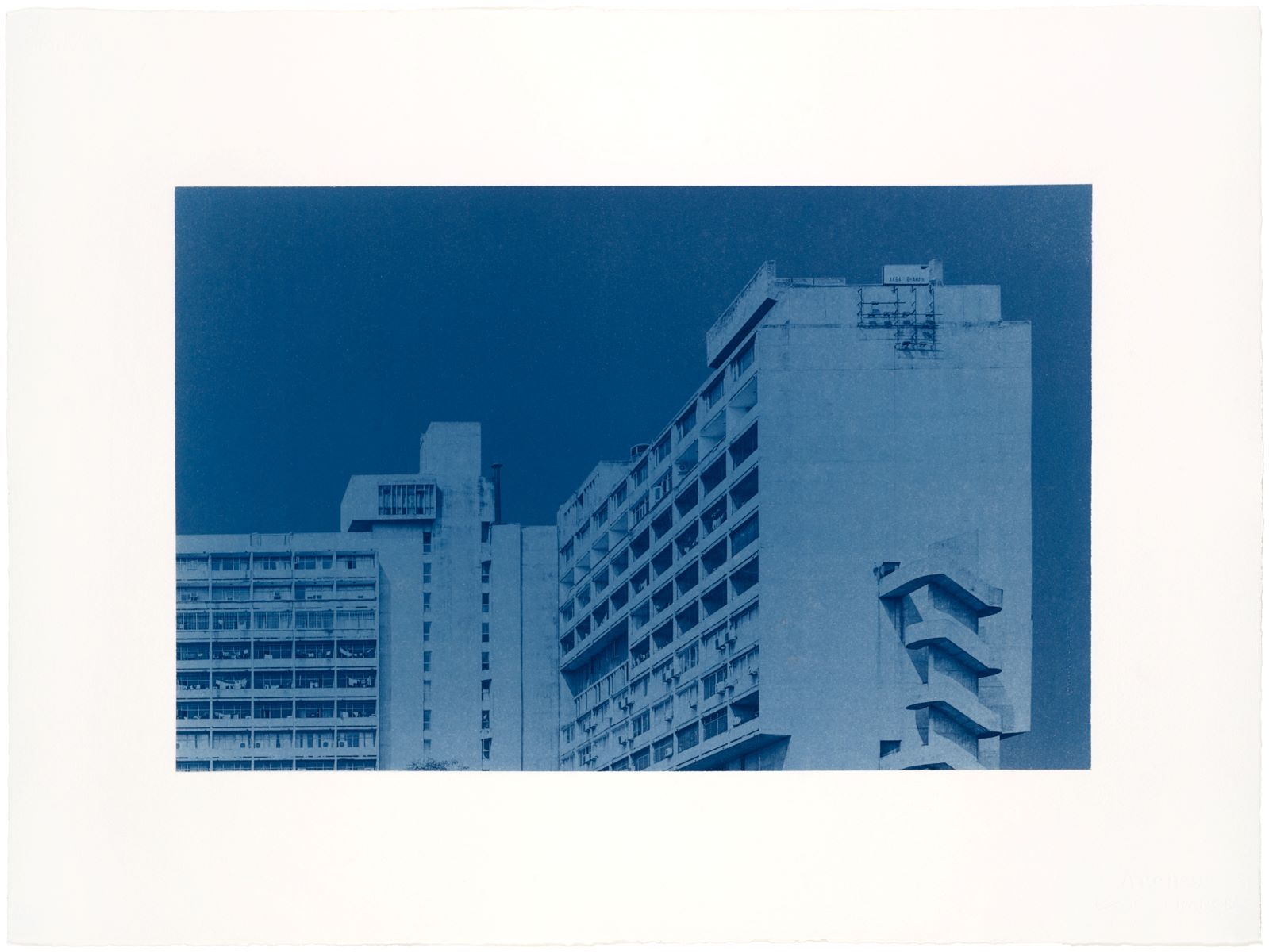

Most of the original buildings, though, are no longer there to narrate the stories as the earthquake destroyed 40 percent of the homes, eight schools, two hospitals and four kilometres of road in Bhuj. The buildings that remain tell the story of the devastation through their cracks – noticeable markers of recent history which mimic the streets of the old Bhuj city: congested, bottlenecked, organic, dead-ended. The rubble from the earthquake choked the narrow streets and blocked the first responders and emergency servicemen from reaching the affected areas. As the local adage goes, earthquakes don’t kill people, buildings do.

Disasters, whether man-made or natural, have historically presented the opportunity for rapid change. The Gujarat government, along with active regional NGOs, like the Kutch Nav Nirman Abhiyan (KNNA) and the Environmental Planning Collaborative (ECI), took the 2001 earthquake as a chance to replan the damaged old city block using a Land Adjustment Scheme². After initial discussions, decision-makers were provided with two options: the total relocation of the old city to a new Bhuj, or the replanning and rebuilding of the old city itself.

After lengthy public discussions and protests, a middle ground was forged which suggested partial reconstruction and partial relocation. A detailed development plan was proposed recommending the paving of new wide roads and loops that offered better access and connectivity of the walled city to the surrounding districts. Areas for city level infrastructure, like water supply, sewerage, storm water design and public buildings, were also identified.

The residents, however, were apprehensive about abandoning their 500-year-old settlement and readjusting to the city outskirts. To calm their fears, a new town planning scheme was developed: those who wanted to stay in the old city and who could produce legal documents of their plots had to contribute some land that could help connect the dead ends, provide arterial roads, open spaces and other infrastructure. The buildings that were destroyed faced land deductions ranging from 10 to 35 percent based on the area they occupied. And the buildings which were still standing were spared from the land deduction with road layout done keeping them in mind. The other residents who wanted to resettle quickly, or those who could not produce legal documents of their housing, were incentivised to move to resettlement colonies with much bigger plots than what they previously had.

Sardar Nagar

The need for shelter immediately after the earthquake was fulfilled by temporary relocation sites provided by the government; however, one such location, Sardar Nagar, which sits on the eastern side of Bhuj, threatened to become a permanent slum of 2,000 families.

KNNA and the Hunnarshala Foundation (HSF), in collaboration with the local government, were invited by some of Sardar Nagar’s residents to help devise a rehabilitation plan. Many community members had been tenants in old Bhuj, for whom the earthquake rehab packages did not sufficiently provide for. Unlike other resettlement colonies in Kutch, this one had a heterogeneous population of 16 different ethinic groups.

HSF, a collective of building experts, social workers and activists, devised the masterplan of the settlement. It was also responsible for the design and construction of the homes, the design and construction of the sewerage and treatment plant, social facilitation, and coordination with local authorities and banks. A combination of community knowledge, personal verification and legal frameworks were used to arrive at an eligible list of homeowners.

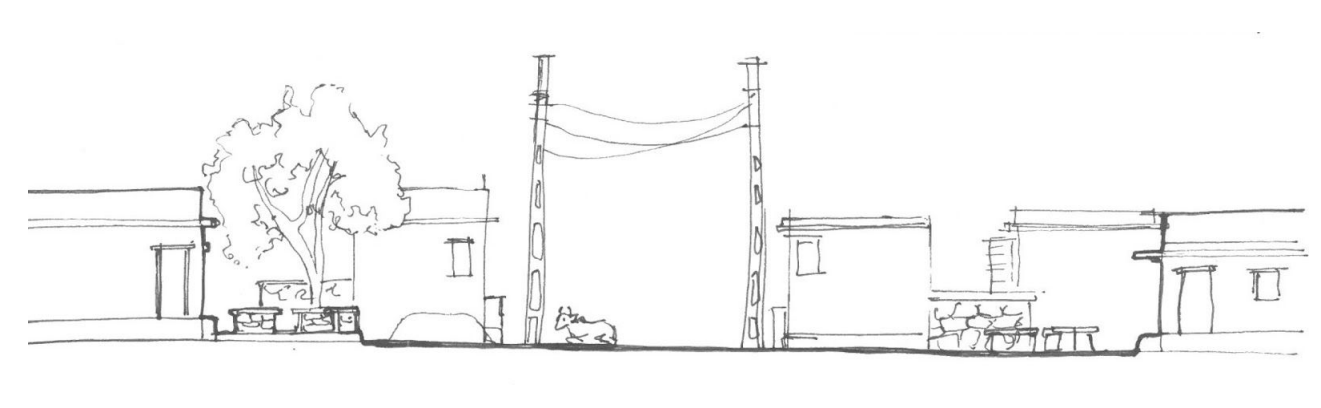

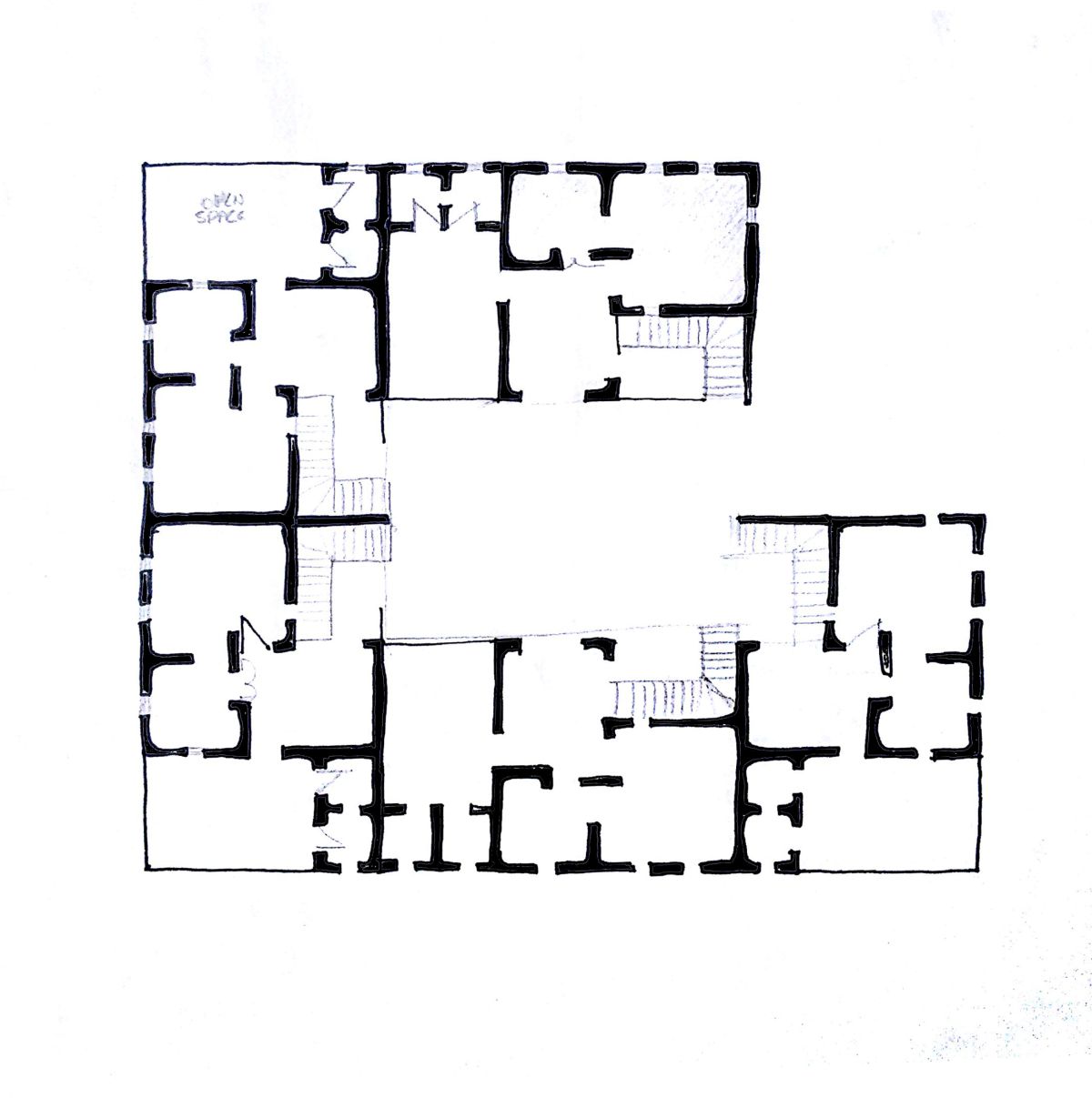

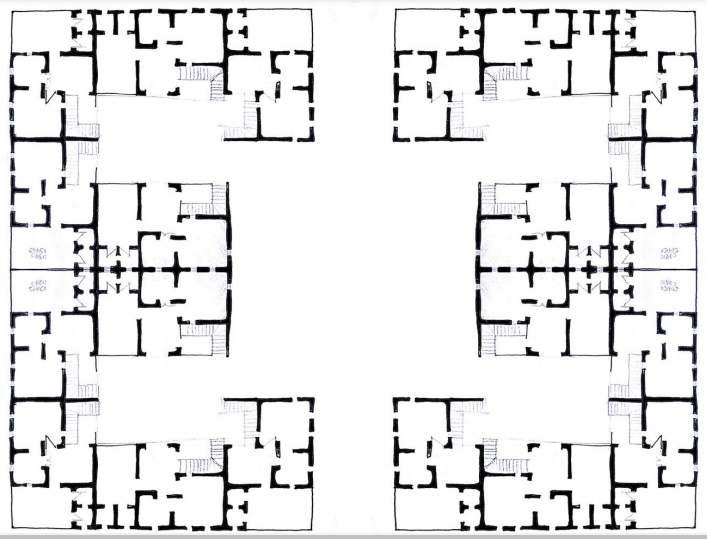

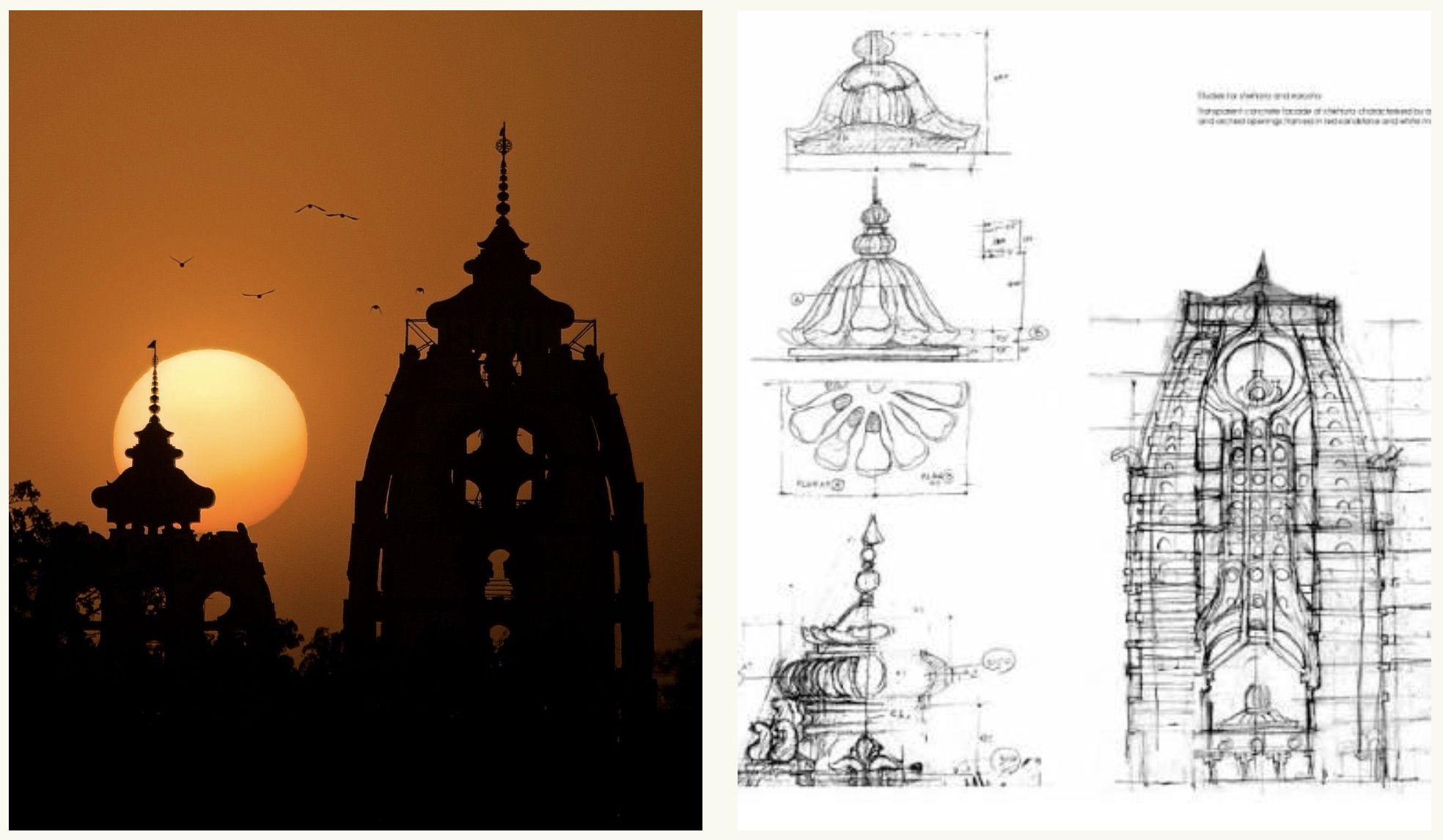

According to Sandeep Virmani, the director of HSF, the collective developed the masterplan by exploring how a village can be inside a sector rather than outside in the outskirts. The housing typology was therefore influenced by the working principles of courtyard-community-living in the old city – a means towards climate control, privacy and security, as well as towards finding solutions to several of the modern needs and problems of growing cities. The plan accommodated the networked, porous quality of traditional rural settlements of Kutch by introducing a hierarchy of interconnected community spaces that vary in level of privacy (from the otla, or sitting bench, to the faliya, or familial courtyard)³ .

The whole resettlement of Sardar Nagar was built in five phases: the first three phases were built by HSF, after which the government took over and made plotted rows. The initial phases included housing clusters with five to eight houses set around a communal courtyard. The smaller clusters were then combined around a larger communal courtyard. Apart from the housing, spaces were demarcated for three schools, a commercial market and an allotted space for informal markets to thrive.

The buildings that remain tell the story of the devastation through their cracks – notice-able markers of recent history which mimic the streets of the old Bhuj city: congested, bottle-necked, organic, dead-ended.

Insufficient funds and the will to use sustainable building materials encouraged HSF to explore low-cost, earth-construction techniques, like stabilised earth blocks, rammed earth, and recycled china clay waste. The houses needed to be built with flexibility and adaptability in mind – thus, they were designed for incremental growth.

Over the years, daily life needs, aesthetic preferences and aspirational paint jobs have slowly overtaken the spotless exposed rammed earth walls and minimalist courtyards. This is the success of the owner-driven and community-participation-based model of HSF, where the people are given the power to design with the architects and slowly overtake when they leave.

Be it the old city reconstruction project or Sardar Nagar housing, no ‘people-centric’ project can be successful without the resilience of the locals and their generosity of spirit. By multiple successful examples of reconstruction, Bhuj has shown the world a way of reconciliation through, as Virmani said, Parampara, a Sanskrit word meaning tradition combined with the process of change. This is in keeping with the syncretic cultural ethos of India, which has always upheld a diversity of thought and accommodated the new into the traditional, renewing and nourishing the old.

Drawing –

The article was first published in Red Envelope Journal by LWK + Partners.

Photography © Nipun Prabhakar

References –

- Adapted from: https://aif.org/remembering-the-2001-gujarat-earthquake/, but verified by the locals.

- Byahut, Sweta. “Post-Earthquake Reconstruction Planning Using Land Readjustment in Bhuj (India).”

Journal of the American Planning Association, vol. 80, no. 4, Oct. 2014, pp. 440–41. DOI.org (Crossref),

doi:10.1080/01944363.2014.989132 - Gillick, Ambrose. Synthetic Vernacular: The Coproduction of Architecture. The University of Manchester,

2013.