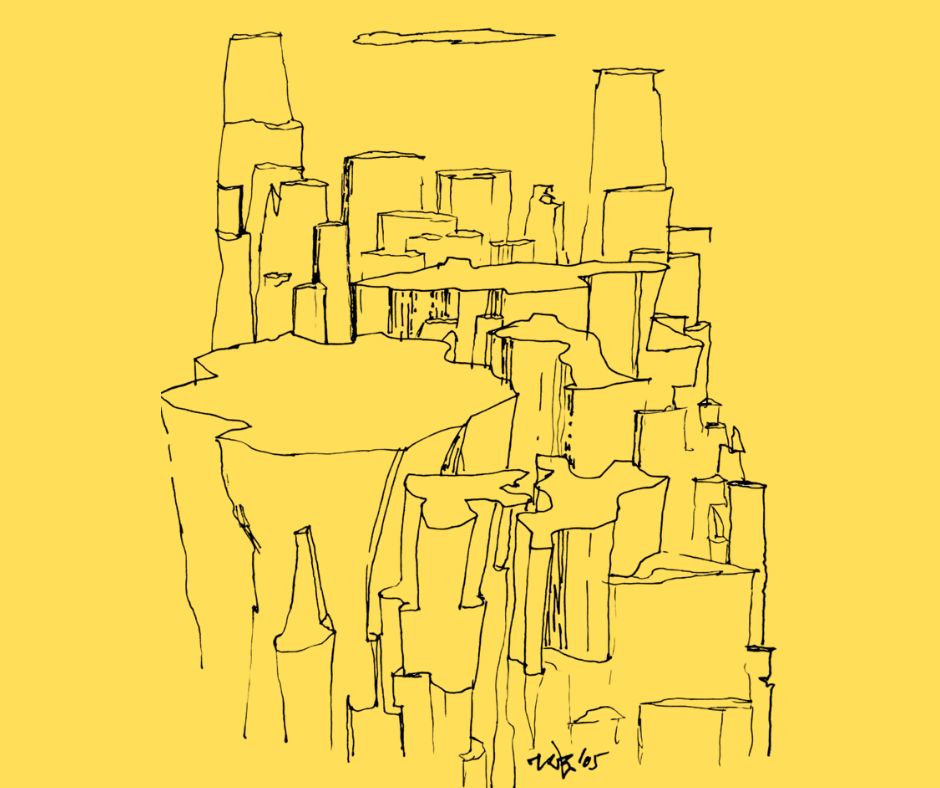

Discussions on urban planning tend to be caught in a largely unresolved tension between two opposing vectors. On one side are citizens whose articulations spring from a recognition of the impact of urban failures on their lives, speaking largely from personal perspectives. On the other side is the establishment responsible for urban planning and implementation: politicians, bureaucrats, and planners who claim an overview free of bias, tending to frame planning as an arcane technocratic discipline whose complexities are best left to the capabilities of experts.

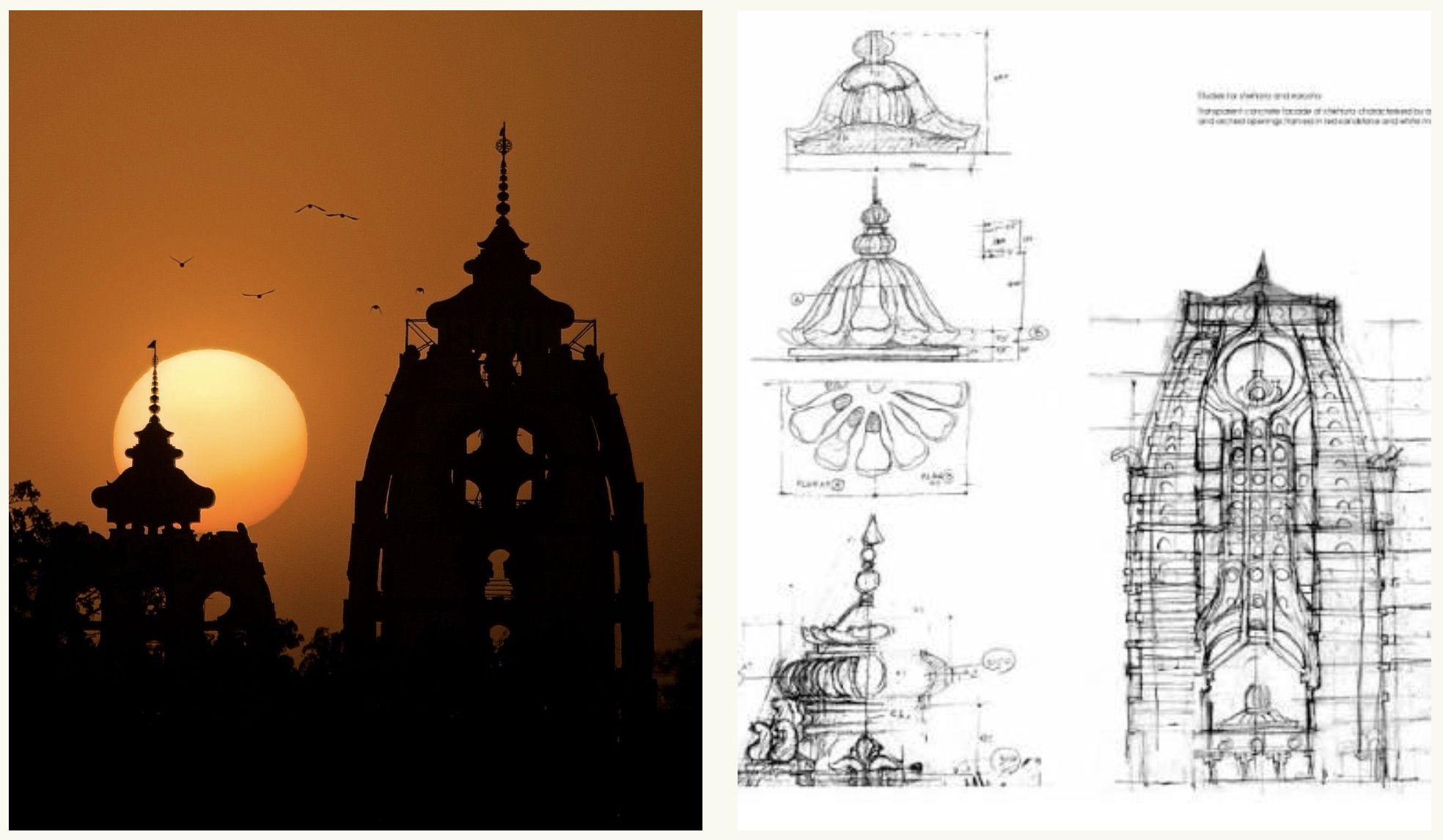

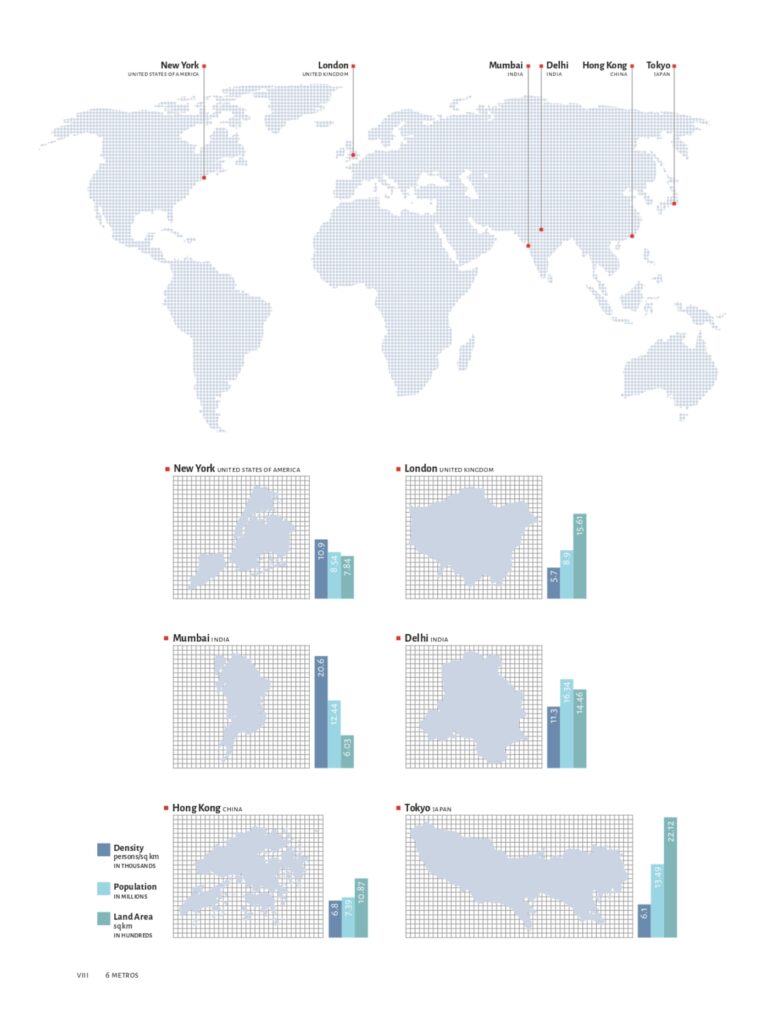

The book bypasses this tension by choosing a comparative approach, looking at urban planning and implementation across six metropolitan cities across the world: London, New York, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Delhi, and Mumbai, effectively covering a range of two Western, two East Asian, and two Indian cities. By covering this diverse range of cities while applying a common analytical framework to all, the study offers a dispassionate overview that reveals the range of possible choices along each vector of analysis. Through this approach, it becomes evident that the physical and logistical conditions of a specific city are not factors that are so complex and deterministic to the extent they typically constrain the discourse on urban planning, and the foundation of planning must begin with an idealistic vision of urban life. This offers a common humanist ground to both citizen and planning expert. As the book states early in its analysis,

“Every construction by man is an intervention in the

natural environment. Each such intervention begins with an idea. The construction is in the mind before it happens in the real world. What happens in the mind is what we might call planning, and the final physical outcome we could call its implementation.”

It is rare, if not unprecedented, to find this type of comparative study of cities. Other comparisons have tended to restrict themselves to specific geographical regions or focus on specific topics such as urban economics, so this book may well be laying the foundation for a new field of comparative urban planning. The original ground this book stakes out is the range of geographies covered as well as its comprehensive overview of urban planning and implementation, analysing each city under ten categories: (i) Planning Process and Implementation, (ii) Acquiring Control Over Land, (iii) Land Use and Zoning, (iv) Transit, (v) Housing, Planned and Unplanned, (vi) Open Spaces, (vii) Amenities – Education, Health and Other, (viii) Urban Density, (ix) Urban Form, and (x) Urban Fabric (analysis in this last category is confined to Mumbai). One category missing in this analysis, that would have made this a well-rounded approach, is the question of how cities finance the implementation of urban plans, particularly the room they are granted to raise their own resources or statutory obligations on upper levels of federal governments to fund the development of cities – limitations that are particularly severe in India.

A major strength of the book is the layering of its presentation by structuring the text into two volumes. ‘Signposts,’ the first volume, outlines the approach, presents the key beliefs, delineates a brief history of urban planning and implementation for each of the six cities, and captures the analysis under all ten categories. ‘Mappings,’ the second volume, lays out the basic research and data for each category of analysis under further detail. Back Matters included in both volumes, contain glossary of key abbreviations and terms, detailed listing of data sources along with relevant weblinks, and bibliography.

The two volumes contain appendices that present specific topics in greater detail. This structure makes it a book that transcends singular readings to invite multiple dives of varying depth into its analysis, opening the possibility of this book evolving into an anchor for many further research projects on urbanism.

The study is frank in its approach, revealing a set of core beliefs on urbanism before it begins its analysis. The beliefs, analysis, and recommendations laid out in the book constitute too vast a territory to either summarise or analyse here, but two key and interrelated points that typically fail to get recognition in urban plans, especially in India, are worth highlighting. The first is that land must not be treated solely as a commodity to be traded on the market for it has the unique trait of being immutable in both quantity and location, and therefore calls for a different regulatory framework to recognise that, while some land can be subjected to the compulsions of markets, all land cannot be treated on the same basis. This leads to the second key point: large sections of the population of cities, particularly in the developing world, do not cross the threshold of affordability to enter markets on land, whether for ownership or rental, and planning must acknowledge this by managing land to cater to their needs for housing, work, and amenities through means other than markets.

While cities have existed since time immemorial, they have become a specialised subject of study only recently. “6 Metros: Urban Planning and Implementation Compared” is a book that is unquestionably worthwhile and can be considered a milestone in the field.

The depth and width of the text are formidable, but this demands an overarching framework to fully comprehend it, and one wishes the initial chapter on core beliefs had taken a broader view to summarise a philosophical perspective of the urban condition.

Notwithstanding this, the new ground the book breaks in comparative urban planning, the wealth of data and analysis it presents, and the layered structure of its presentation, are likely to make it a reference point provoking a multitude of further studies in urban planning.