In the grand narrative of Chandigarh, the city envisioned as independent India’s postcolonial modernist utopia, the recent controversy surrounding the demolition of Rock Garden’s wall for additional parking space for the High Court is more than an isolated conflict. It is a moment that crystallizes the ongoing tension between contradicting visions of heritage preservation and development, and its overall impact on the citizens. To understand this, we must turn to history—not just of the Rock Garden itself but of Chandigarh’s very foundations, where questions of who shapes a city and who is shaped by it have persisted since its inception.

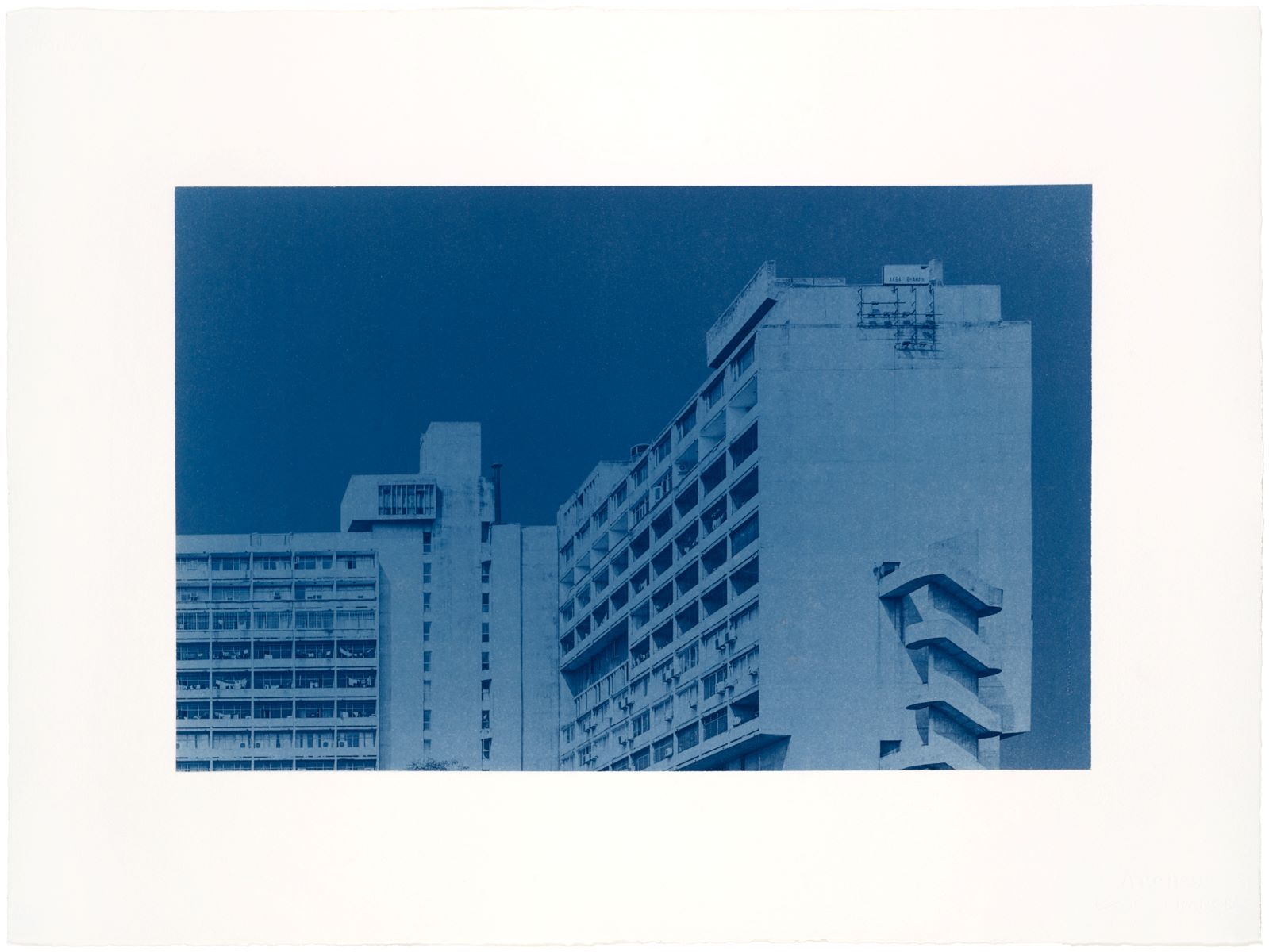

Le Corbusier’s master plan for Chandigarh emerged from the ashes of the partition as an elite-driven project of order imposed upon an unfamiliar landscape. Throughout Chandigarh’s history, several key decisions and initiatives have been implemented primarily to serve the interests of the elite. As Ravi Kalia notes in Chandigarh: The Making of an Indian City, Chandigarh was conceived as a clean break from the past, a meticulously controlled experiment in modernist urbanism.

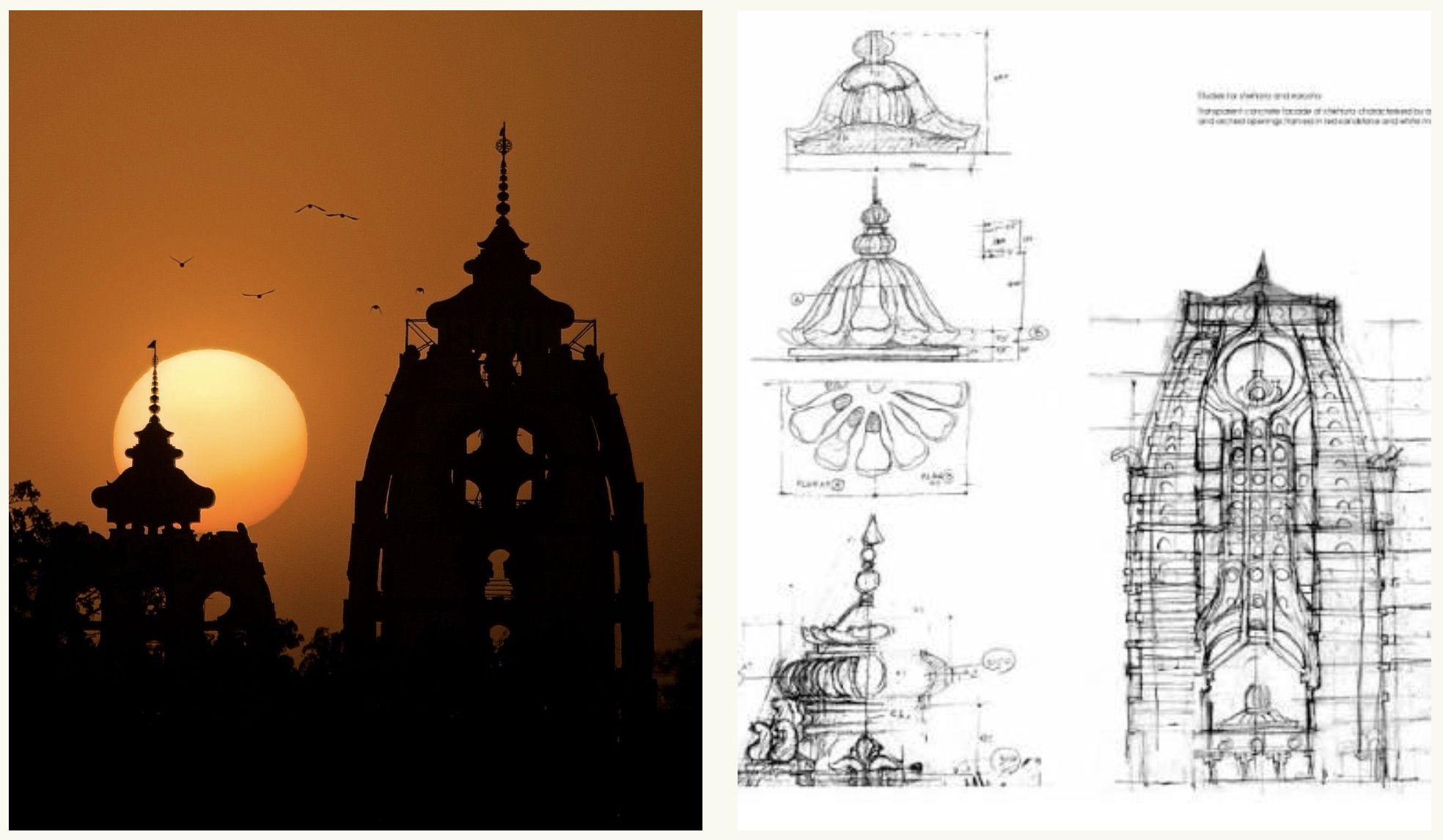

The intention was to construct a new capital for Punjab that would symbolize India’s break from its colonial past, embracing rationality, functionality, and progress. However, as Kalia highlights, this vision was deeply rooted in Western ideals of planning and did not account for the socio-cultural dynamics of its inhabitants. The grid-like sectoral planning, inspired by Corbusier’s principles of zoning and hierarchical organization, prioritized clarity and efficiency but ignored the rhizomatic patterns of community life that traditionally shaped Indian cities.

The process of city design and city making has been considered as an application of set rules and regulations that are neutral and validated on the grounds of being in the interest of the people. However, in Chandigarh, like in several other examples of designed cities in developing nations, the neutrality of spatial design is often a misconception. Invariably, the impact of the city design is unequal across different sections of the society.

Madhu Sarin’s groundbreaking work, Urban Planning in the Third World: The Chandigarh Experience provides critical insight into how administrative decisions in Chandigarh have historically been partial towards the elite concerns over those of ordinary citizens. Sarin documents how the city’s administration has consistently approached development through a technocratic lens, where the articulate sections of the population demand more, rather than less—showing that the “neutrality of planning is a myth.”

Within the present framework of postcolonialism and modernism, today’s Chandigarh enters into a paradoxical urban situation, where on one hand, it looks inwards to meticulously protect its built heritage against the forces of globalisation and world capitalism, while on the other, the urban elite minority demands greater privileges, and in the process destroys the very heritage that the city pledges to protect.

The demolition of the Rock Garden wall is an exhibit of this urban paradox. The decision to sacrifice a portion of the Rock Garden wall exemplifies what Sarin identified as a persistent problem, “The planner’s (and here might we add, the ‘privileged class’) preoccupation with the physical aspects of development at the expense of social implications.”

Created by Nek Chand Saini, a government road inspector who secretly began constructing this fantasy landscape from discarded materials in 1957, the Rock Garden represents one of India’s most remarkable examples of outsider art. It was built surreptitiously in defiance of official planning and emerged as a grassroots counterpoint to Corbusier’s rigid geometries. It is a space born from waste and creativity, woven from the discarded remnants of a planned city that had no room for improvisation.

The government’s intermittent attempts to regulate, alter, or even alter parts of the Rock Garden mirror a deeper discomfort: the challenge of integrating unsanctioned, people-driven spaces into a city whose very ethos resist bottom-up interventions. The wall does not just block a view—it signals an erasure of the improvisational spirit that has given Chandigarh its rare moments of divergence from the master plan.

The Chandigarh experiment demonstrates that neutrality of planning is problematic as it can be an instrument for serving the interests of a particular class. Designers and urban planners have the choice to either support the interest of the ruling minority, of which they frequently form a part, or they can work towards altering the structure of domination by supporting the majority citizens. Therefore, we call out to the design practitioners of the city to exercise their agency to critique the emerging urban contradictions and create the conditions that heighten an awareness of issues like the demolition of the Rock Garden wall.

As Chandigarh’s authorities proceed with the demolition of a 25-foot stretch of the Rock Garden’s outer wall, what do its people have to say? Many local voices have spoken out against this intervention, decrying it as a betrayal of the very ethos that made the Rock Garden a beloved landmark. Designers, artists, historians, and citizens alike see this as another example of development that disregards lived heritage.

Deepika Gandhi, former director of Le Corbusier Centre, expresses concern “The worrying part is the apathy towards built and natural assets – and the lack of vision to tackle these problems.” Army veteran Brig. K.J. Singh, a long-time resident of Chandigarh, elaborates “Solutions should have been sought from technically competent experts to arrive at a via media, addressing this issue without compromising on either heritage or development.

Moreover, given the social value of the site, the public should have been informed about the demolition before it began.” Another local of the city shares, ”It’s heartbreaking to see my city change right in front of my eyes. And it’s not just Rock Garden, trees are being cut down at an alarming rate all over Chandigarh, especially in the green belt areas that fall under the forest department. Our city is being stripped of its soul, the air quality is deteriorating fast, and we’re cutting more trees to make more room for parking. How does this even make sense? Not to forget the animals and birds that are being displaced because of this massacre.”

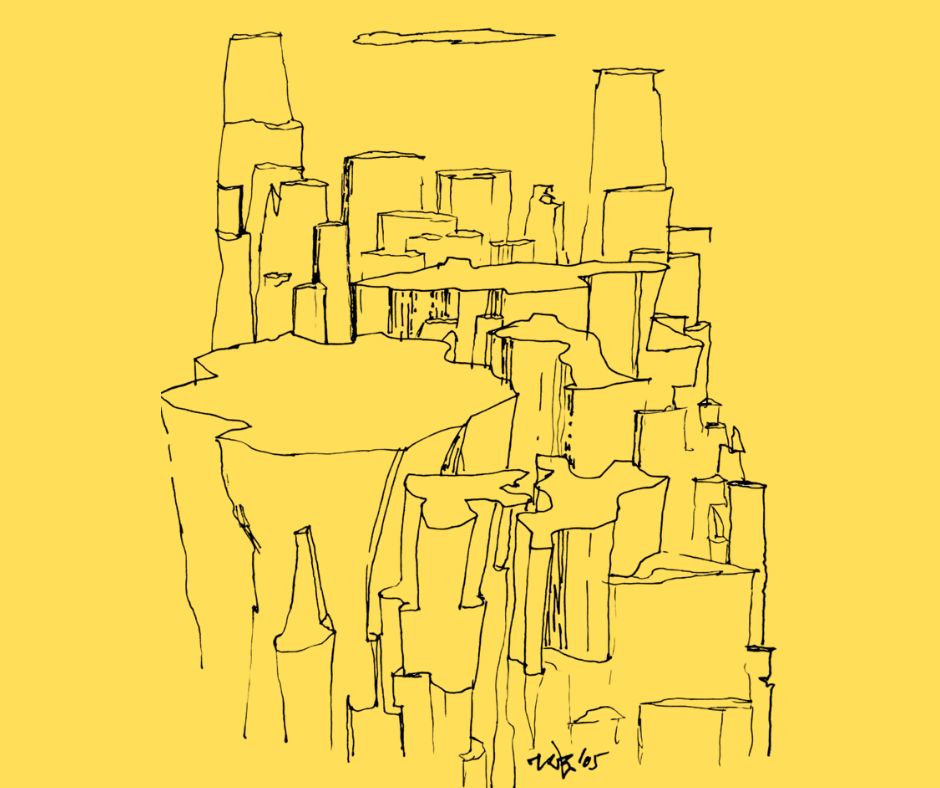

Cities are living entities shaped as much by their people as by their planners. To move beyond the legacy of urban subjects as mere occupants of designed spaces, we must turn to participatory urbanism.

Therefore, this is also a provocation for the citizens of Chandigarh, to raise their voice to open up a dialogue around their right to the city. It calls upon the people of Chandigarh to look into their citizenship–beyond a mere “status” that is allotted by the constitution, allowing them to inhabit a physical space within the city–rather as a lived action, a practice of engaging with the conversations around the city.

Meanwhile, as the battle over the Rock Garden’s future unfolds, Chandigarh stands at a crossroads. Will it continue to be a city dictated by outdated visions of order and control, or will it embrace the messy, vibrant, and participatory nature of real urban life? The answer to this question will determine not just the fate of a single wall but the very soul of the city itself!

Co-Authored by:

Asees Prab is an architect, urban designer, academic-activist and writer. After seven years of teaching and working as a design consultant in India, Asees has shifted her practice to spatial design research, knowledge dissemination and publication at Melbourne, Australia. She recently edited the book ‘Form Follows Roots: Architecture for India 1985-2021’ (supported by the Indian Council of Architecture) and is currently co-authoring her next architectural book project in collaboration with Saakaar Foundation.

She has published several peer-reviewed research papers and filed more than five design patents. Asees is the recipient of Young Architect of the Chapter Award (Indian Institute of Architects), RMIT Research Stipend Scholarship, Anita Sharma Memorial Award, Sanjiv Bhandari Scholarship, H.S. Kohli Memorial Award, and Principal A.R. Prabhawalkar Award.

At present, Asees is pursuing a PhD through creative practice research at RMIT University, Australia.