Visualise this word: development.

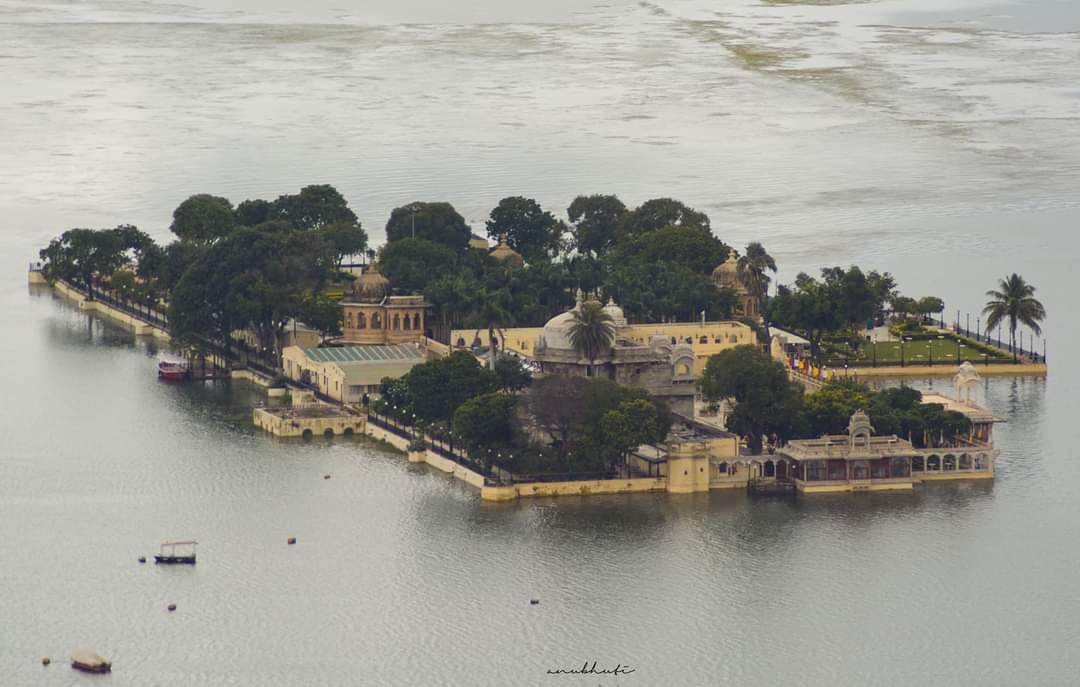

Does an aerial view of the modern city come to your mind, adorned glass and steel and concrete? Colossal skyscrapers with light glinting off the glass, the row of tall buildings a towering flex of the city’s might and power, becoming the horizon of the city; broad roads and topsy-turvy flyovers meandering through the buildings, ever-buzzing with cars, indicative of a city that never stops, a city with wealthy citizens living a lavish life.

With the city of Bhopal being relentlessly ‘developed’ under the Smart Cities Mission of India, this vision leads us to wonder: is this what the city really aspires to be, or is it merely driven by the Western vision of a corporate-driven, concrete-studded city? Is this really what the New Smart City of Bhopal wants to be in the New Bharat?

This article attempts to analyse the city’s dreams, aspirations and ambitions through the lens of the Bhopal Smart Road project, which comes under the Bhopal Smart City Development Project. The Bhopal Smart City’s vision, mission and values – apart from being a jumbled jargon of keywords like education, research and smart all dumped into one sentence – states that the four pillars of building this model are ‘World-Class Infrastructure’, ‘Investment Opportunities’, ‘Employment Opportunities’ and ‘Transit Oriented Development’. The intent of the project is “to create sustainable cities that can provide a good quality of life to its citizens”, wherein it seeks to address the ‘issue of urbanisation’.

The Smart Road Project has had two smart roads built by now: the Boulevard Street, running from Mata Mandir to Jawahar Square, and the Smart City Road, running from Polytechnic Square to Bharat Mata Square. The names themselves reveal their intention. The term ‘Boulevard’ takes one to the Boulevards of Paris where this Western Imagination of the urban landscape seems to be derived from. The ‘Smart City Road’, well, it’s a smart road, what else do we name it as? Along with that, an English name always bodes well on how modern the city is and reflects what it aspires to be.

The Boulevard Street and the Smart City Road are both 8.5m wide. The roads are provided with stormwater management systems, street lighting that efficiently uses solar electricity, service lanes for bicycles and broad footpaths. The dividers and the sides of the roads are planted with palm trees and small flowering bushes and shrubs. The utility ducts that carry internet and communication cables run underground.

The development agenda – one that is driven by the money-minting ambitions of a capitalist economy – mandates a developed city to provide ‘world-class’ (read as: ‘Western-class’) infrastructure, broad roads and metros to be able to mobilise a large amount of population from one place to another, and hence create thriving local economies. It is also meant to lure corporations to the city in order to expand the workforce and the revenue generated to the government from taxations. This is why, in a video proposal submitted by Bhopal Smart City to the Central government, an aerial view of Bhopal at present and then the view of a transformed Bhopal is presented. This aerial view of transformation again reveals how development is viewed as in the minds of the authorities: lesser green cover, more tall

buildings, broader roads and metro lines piercing through the city, regardless of its necessity in the public realm. Moreover, the victorious music in the video – one akin to the themes of power – glorifies the project, as if saying that this proposal is the end to all of the city’s woes.

The visuals of the Boulevard street in the video proposal show a very clean, aesthetically appealing city: busy men suited up and carrying briefcases, waiting for their bus to arrive and young, slim and white men and women using the public areas. The ‘smart’ roads have forgotten to incorporate the needs of its differently-abled citizens, its differently-aged citizens, and most importantly, its brown citizens. Who this development caters to is also derived from the Western Imagination and in this, it’s corporate men and ideal citizens; the smart city doesn’t entertain visual poverty.

On both the streets, what is put in the forefront and what is hidden says a lot about how the city wants to appear.

The small line of cafes at the entrance of the Boulevard Street is a chaotic youth hotspot, but because of the fact that it is disorderly with vehicles parked in any fashion, the authorities covered up the area with a vertical partition so that it doesn’t disrupt the aesthetics of the street and pollute it visually.

On the other side of the road is an area occupied by a line of small shops and one-storey houses, but largely covered with trees. This area again is being uprooted to be able to build commercial complexes and office buidlings. The video proposal shows what the vision of the road is, and clearly, it is one whose elevation looks ‘high-tech’, ‘world-class’ and ‘developed’. It shows the might of the city and the economic power it wields. The road seems to stretch to infinity, looking almost like a virtual simulation. There’s nothing wrong with development but there should be a pre-existing or a projected need for said development, instead of creating a need by making the city a capital investment project.

The problem on the Smart Road is somewhat bigger though. The side of the road has a steep, sloping hill that connects to the heart of the city, but this area is covered with a big slum and the residents have been there for decades. In 2017, half the slums were bulldozed in order to provide space for the road and the residents were relocated to low-income housing built on the fringes of the city as well as to small four-wall tin sheds along the same road that can only be considered as the most primitive form of modern-day housing. An interview of one of the residents revealed that the road was elevated 6 feet from the original road so as to hide the nearly-dilapidated houses on the slope adjacent to the road. Moreover, any building that tried to rise above the road was demolished, all because of the perceived uncleanliness and the visual pollution that these slums seemed to create. This was done so that people have a direct

view of the corporate buildings at the foot of the slope, so that they see a ‘developed’ city, one

where the buildings hide the horizon because it’s all about the elevation.

This situation reminds of the recent ‘greenwashing’ of South Delhi during the G20 summit.

But, right opposite this, the Smart City authorities have started constructing huge concrete buildings that not only rise higher than the road, but also higher than the hill that they sit on, because, again, the taller the important-looking concrete buildings, the greater the glory of the city. The Smart Road puts active effort in hiding the disorderly, poor, unsanitary and visually polluting slums and puts to the forefront the concrete buildings indicative of an economically wealthy, ’developed’ city; an abode to luxury, wealth and culture. Also, the fact that the most polluting material (concrete) is used to create these supposedly clean buildings continues to show that the main agenda of a developed city is merely a visual agenda.

The project seems to imply a set definition of what development means: using city infrastructure to make the city appear developed, instead of actually improving public life. The Smart Road and the Boulevard Street do provide a pleasant ride and help in reducing traffic congestion on the streets. The trees and plants planted on dividers add to the pleasantness of the drive, and also make cycling there pleasurable, but it’s what happens on the sides of it

that dictates urban life. Having been built embracing Western Imagination, the Bhopal Smart City Project fails to create its own identity and evidently, very consciously, emulates the Western meaning of a ‘world-class’ developed city.

Note: All the images are shared by the author.