“Memory’s images, once they are fixed in words, are erased,” Polo said. “Perhaps I am afraid of losing Venice all at once if I speak of it, or perhaps, speaking of other cities, I have already lost it, little by little.”

I have often wondered if Calvino believed his fictional Marco Polo when he wrote the above lines in Invisible Cities. (Calvino 1974.)

Calvino’s observation has resonated with me strongly ever since I first read it. How does one describe a place without diluting its total experience? More importantly, would your memories get lost when you try to bottle them with the constraints of language? These musings have instilled in me a reluctance to write about anything which has personal meaning to me lest I lose it from my possession.

But then, I remembered our house at Kashmiri Gate.

My father’s family had lived at Kashmiri Gate in Delhi for decades before moving away six months after I was born. My parents were part of a joint family like so many others of their generation, co-living with parents and other siblings until it became untenable to do so. After we moved away from Kashmiri Gate, most of my early childhood was spent at our home in Sarojini Nagar in South Delhi. This is the house that I remember growing up in and have a vivid recollection of its physical form.

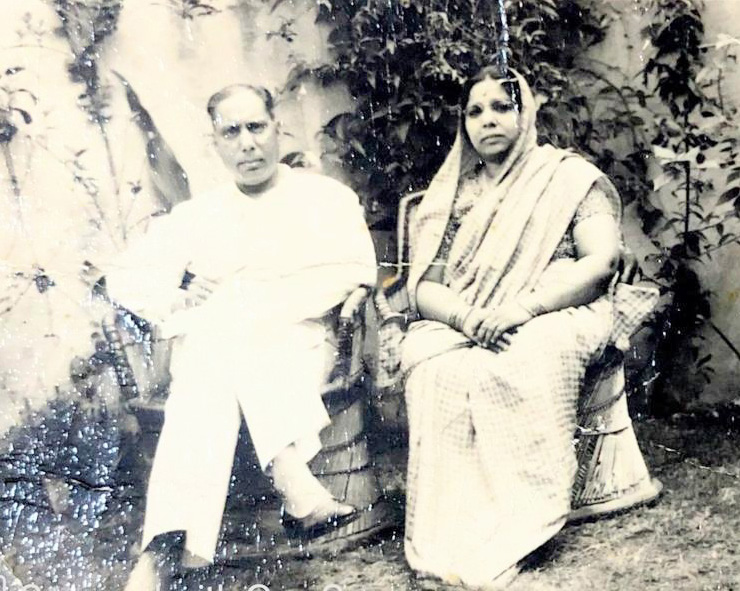

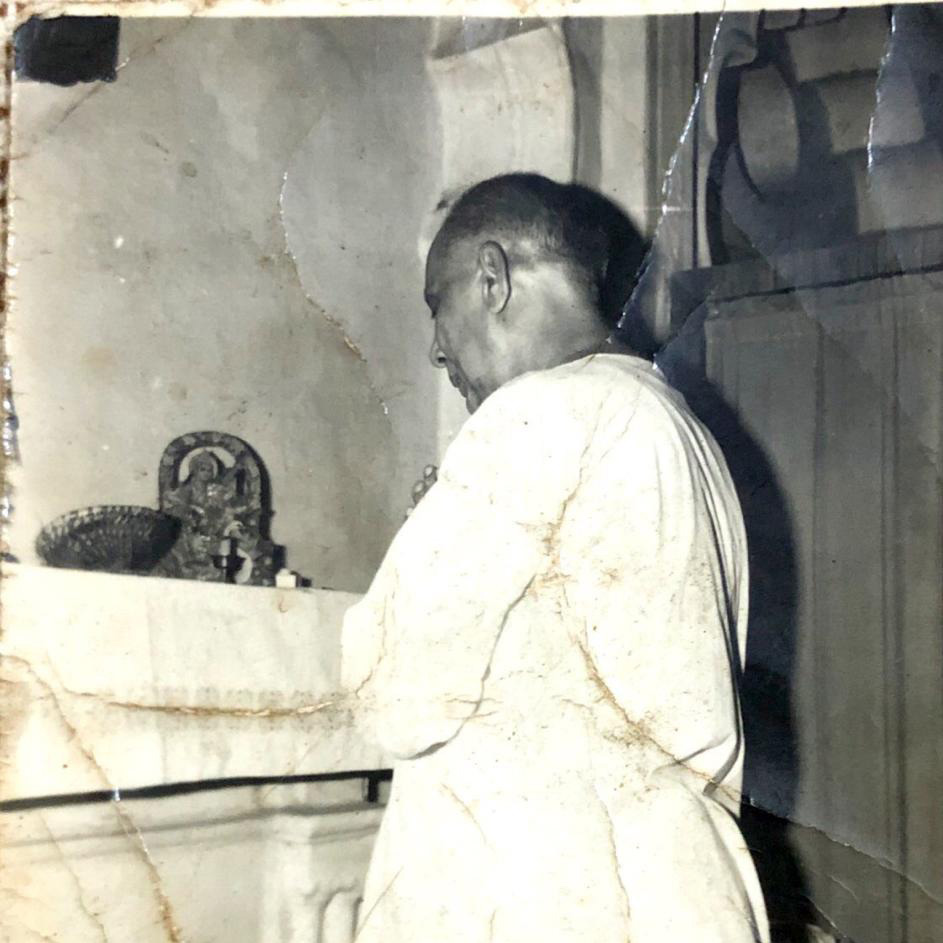

Still, my spiritual home has always been the house at Kashmiri Gate. Conversations around the dinner table always started with how someone (distant relative / friend / acquaintance) used to visit us at Kashmiri gate or how they were the benefactor of some generosity from our family. To me, it seemed like a faraway place where everything was grand and larger than life. Images of my grandfather walking tall in a white kurta-pyjama smoking cigarettes and drinking coffee while consuming books were etched in my mind as a child even though I was born much after he passed away. The verandah where my brother & cousins would run amok while my mother and aunts conversed felt bigger than my school’s playground. I tried to fit in this imaginary household atavistically upholding the values of a bygone era from an early age.

My grandfather was a Professor of Physics at Hindu College. He would drive to the college for his classes and come back home for lunch. After a small nap, he would go back again for a few more hours. His unhurried lifestyle seemed in contrast to his prolific contribution as an author of several books devoted to Physics. He also seemed to have a voracious appetite for having paan – My grandmother’s morning ritual at sunrise included rolling out & stacking 20-25 paans every day in a paan box for my grandfather. He drove fast and was hard of hearing in his later years – a potent combination matching his mordant

humour.

The fragments of my family’s history are preserved in the oft-repeated stories of relatives whose fickle mind is not entirely reliable, but it provides enough details to recreate the setting & atmosphere of the old house. The precinct which enclosed our house along with other homes was known as Damodar Bhavan. It had a wooden gate colloquially known as the ‘phatak’ which also had a smaller pedestrian gate built in. After entering the phatak, there was a staircase on the left which went up to a house where my father’s maternal uncles and aunts stayed with their families. On the right, most of the houses were occupied by Maharashtrian neighbours – Ratnaparkhis & Aardeys. There was a small kothri on the left under the house of the maternal uncle that was inhabited by the family of a mechanic. The roots of a large Neem tree started from this Kothri and stretched out up to the top of the terrace of our maternal family’s house. At the end of the cul-de-sac, another boundary wall emerged with a metal gate decorated with an arched profile with two buttressed supports in plaster and paint. An overgrown ivy vine wrapped itself around the arched gateway and marked the threshold of our house.

From the Phatak, the road on the left would lead to an area called Chabi Ganj whereas the one on the right led to Bada Bazaar. Trips to shahar (Chandni Chowk) were infrequent and had to be traversed carefully by going through Kaudiya Pul which led to Dariban Kalan & Cheerakhana and Nai Sarak.

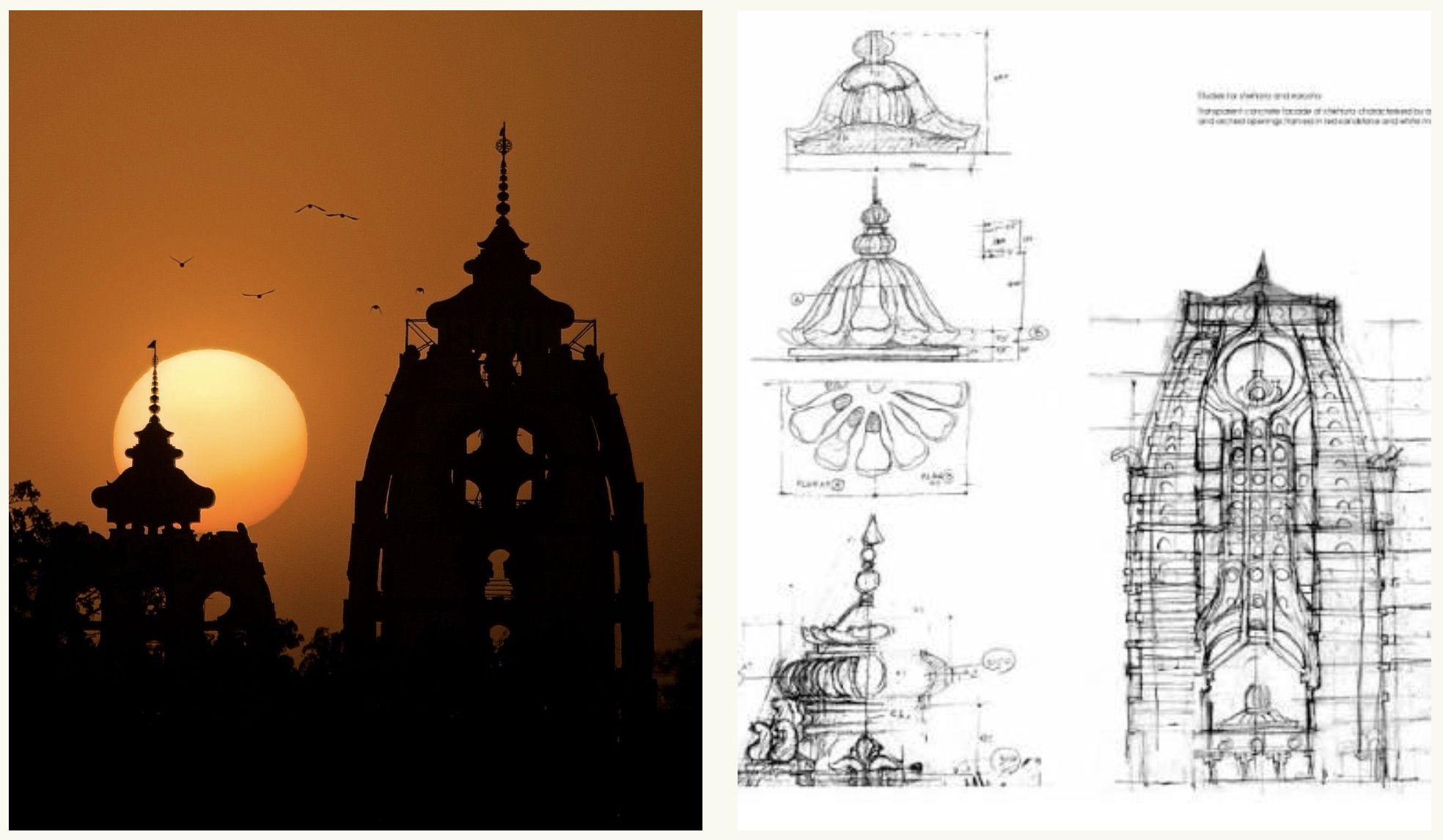

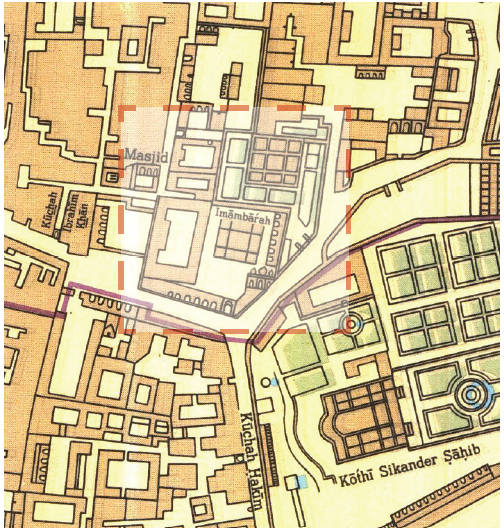

A fortuitous conversation with the elders of my family first piqued my interest in the architecture of the old house when they described the entrance of the house with an arched wall as a ‘mihrab’ wall. I probed further and realised that this was a vestigial connection to our home’s history as an Imambara which was part of a larger complex connected to the Mosque behind. Suddenly, a connection between the architectural space and my family’s memories of the house became clearer.

Guests trickled in from time to time and it was not unusual for them to come unannounced. Some of them were out-of-town relatives who would extend their stay with us. Most other times, it would be neighbours, university students & friends coming over for a chat. The water was always boiling for making copious amounts of tea that were passed around within the house from early morning to late at night. There was no such thing as a bad time to have a chat or a cup of tea. The living room remained what it always was – a majlis.

The discovery of our house being an old Imambara presented a unique opportunity for me to try and get a closer understanding of the house through its architectural past. I started by trying to locate the house in my copy of Ms Lucy Peck’s book on Delhi’s built heritage (Peck 2005). As I turned to the section on Kashmiri Gate, I realized that there was a highlighted building almost exactly where the house was supposed to be. The book mentioned it as a ‘Colonial House, 19th Century’. Even though there was no copper figure of the INTACH logo next to it, it was recognized by the author as a significant structure to make a note of it in her book. It felt like a clue.

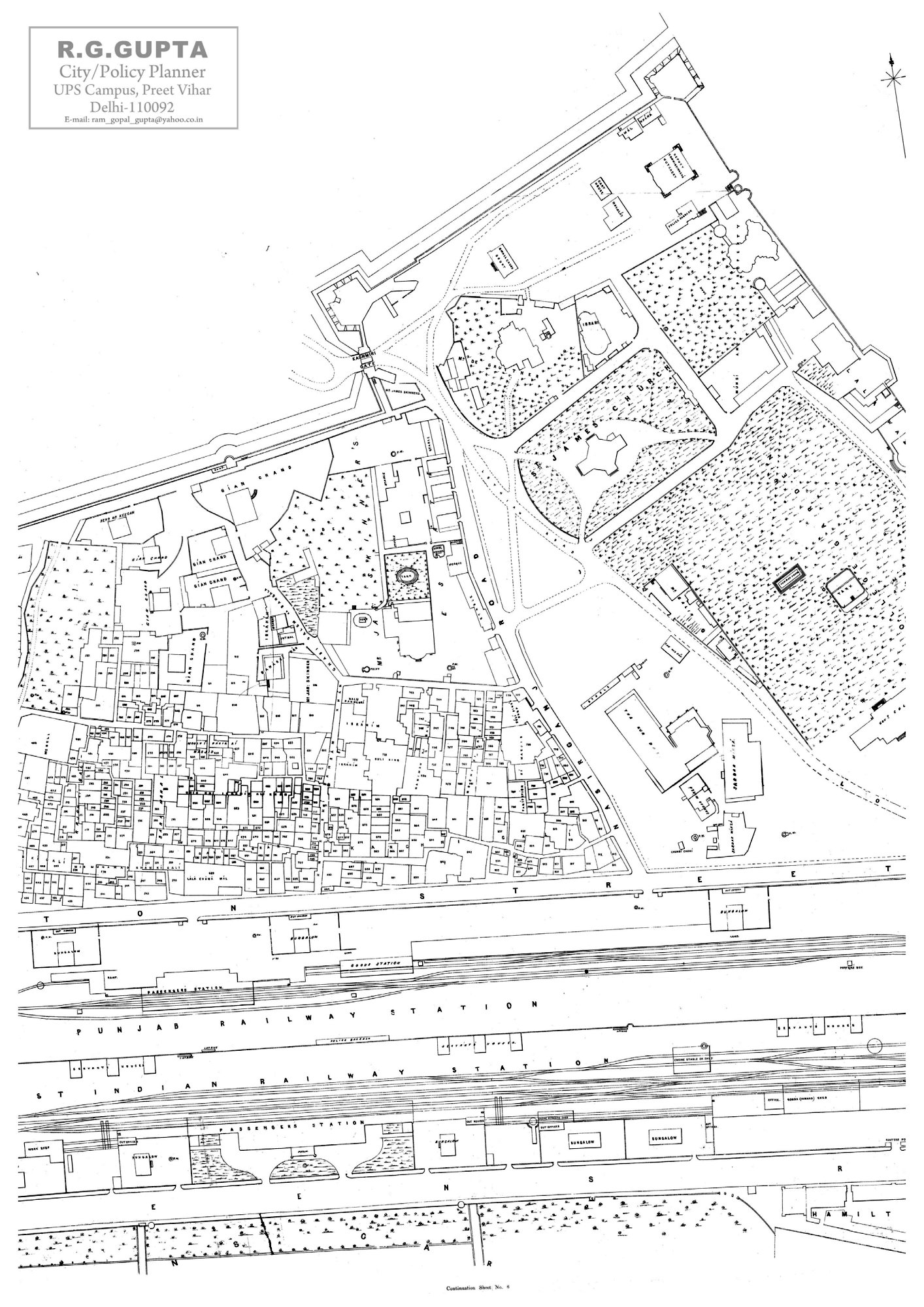

I decided to pursue this direction a little more and tried to locate more Maps of Delhi that may contain any more information on the Imambara. My first break came when I stumbled on the internet to an amazing trove of information on Mr R.G. Gupta’s website¹ which had the 1873 Map of Delhi surveyed for the Municipal Committee of Delhi. It is an amazing map clearly showing the plot divisions, roads and important landmarks. While the smaller plots are relegated to just being labelled as plot numbers, significant properties are marked with owners’ names. As I tried to point out the location of our house on this map, I was surprised at the similarities between the old and the new urban fabric. Most of the old streets had survived. Larger plots were broken up but remnants of the old larger structures remained. As my roving finger stopped at the location of our house, I squinted to read the name – Mr Jas: [James] Skinner.

Lieutenant Colonel James Skinner was an East India Company officer who despite his Anglo-Indian lineage had risen to the ranks of the company. He raised two cavalry regiments for the British that are still part of the Indian Army. He had also commissioned the St. James Church which is still active and is in close vicinity of the Kashmiri Gate house².

Feeling a tinge of excitement over the discovery of our old home being part of James Skinner’s estate, I felt that there may be other historical records of interest. I connected with Ms Peck on a public internet platform asking for help on this matter. She replied in affirmative and helpfully shared an email address to correspond with. I shared with her the context of my query and asked her if she would have any other records of ‘Colonial House, 19th Century’. Then, I waited for her response.

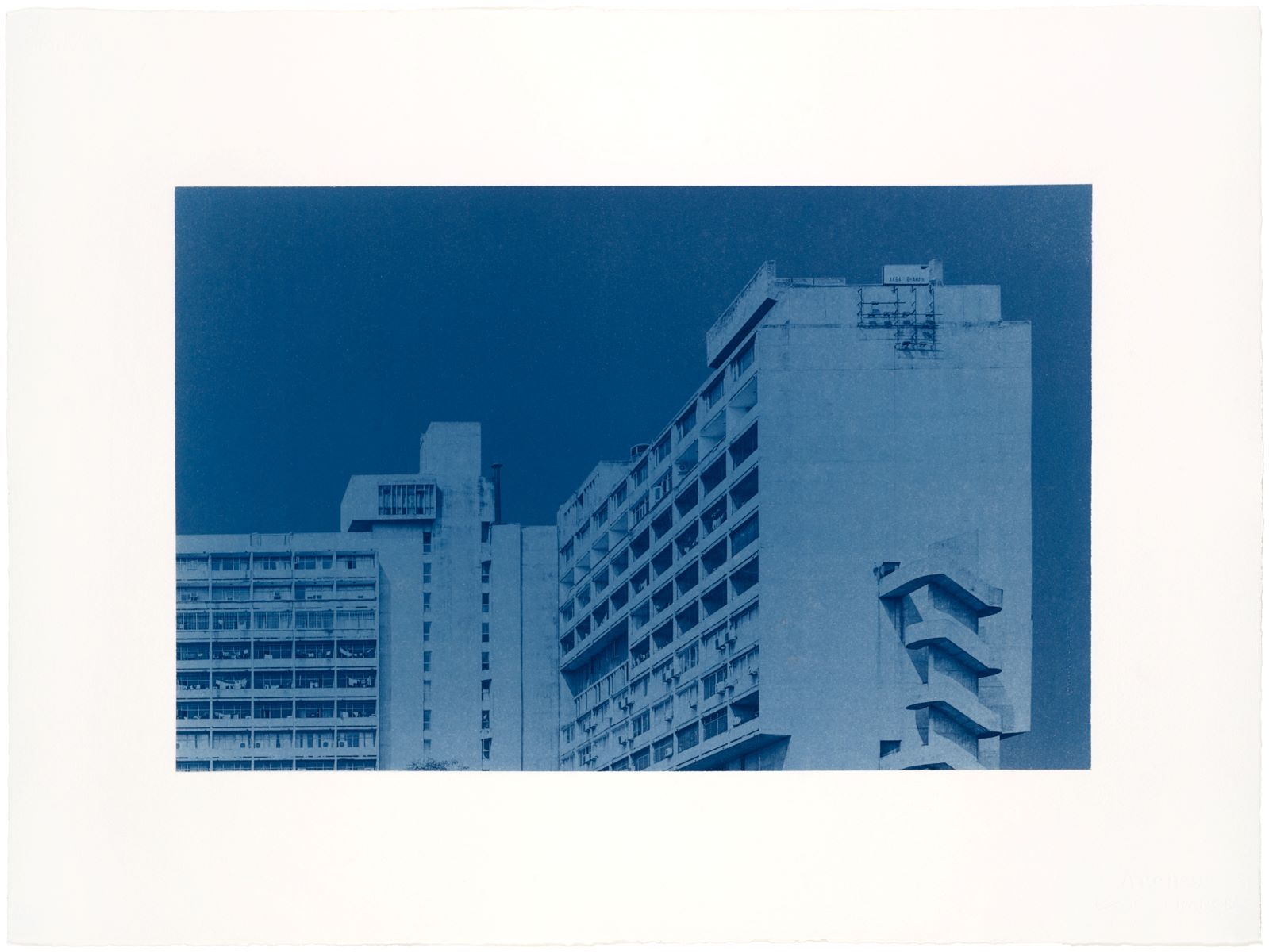

Photo Credits: Ms Lucy Peck

While researching for more information, more than a few references pointed to the wonderful map of Delhi in the 1850s by Thomas Kraft and Eckart Ehlers³. Upon acquiring a good-resolution version of the map, I was delighted to find that the Imambara was listed along with a symbolic elevation of an arched court at the location of the old house. Although I knew that the arched court illustration was symbolic, to me it felt real as if the cartographer’s lines had traversed through the veranda and felt the cool shade just as I had imagined through my childhood.

Meanwhile, Ms Peck responded to me in an email whose contents I am sharing here with slight edits for maintaining context:

“…I took some photos (attached) of a building which I recorded as an Imambara (even though it is now a commercial building), and I think it is the building marked with a black square on my map, which is in the same place as the hatched area on the old map. You will see that it is partly an old building, with remains of late-Mughal decorations still visible. The upper floor looks as if it was built in the 20th c – perhaps the 1930s. There is a small mosque just in front of it, visible on Google Earth. The photo also attached.”

I shared the photos with my family and was elated to find that Ms Peck had sent us the photos of Damodar Bhavan despite being not fully sure if it was the correct building. I finally saw the Kashmiri Gate home in its physical form, or at least what was left of it.

From the photos, little remained of the original house or the Imambara now. Most of it seemed to have been transformed into a commercial hub for automotive spare parts. The lawn had been converted to a loading bay for tempos. The verandah and the rooms inside had been hollowed out and divided into small shops selling car parts. The upper storey seemed to have survived the onslaught at the Ground floor and a few Window details and cornices sheepishly tried to blend in with peeling plaster & paint into the tin roof overhangs along with concrete & brick tumours on its façade.

Photo Credits : Ms Lucy Peck

Photo Credits : Ms Lucy Peck

Photo Credits : Ms Lucy Peck

Photo Credits : Ms Lucy Peck

I felt restless every time I looked at the photos. I tried to appreciate the fragments of modest details in the walls, thought about the moonlit courtyard and tried to feel reverence for my ancestral home but this did not seem like the house that I had connected with. Polo’s prophetic lines came to haunt me again – After all, photographs frozen in time do seem closer to the written word in a way.

I needed to confront the reality of the physical form of the house by making a visit in person. If the house was as compelling as I thought it would be– its spirit must exist even now. Perhaps, I could peel away the neglect and apathy that I saw in the photos using my sensibilities as an architect to connect with our shared history. I had to travel back to Delhi.

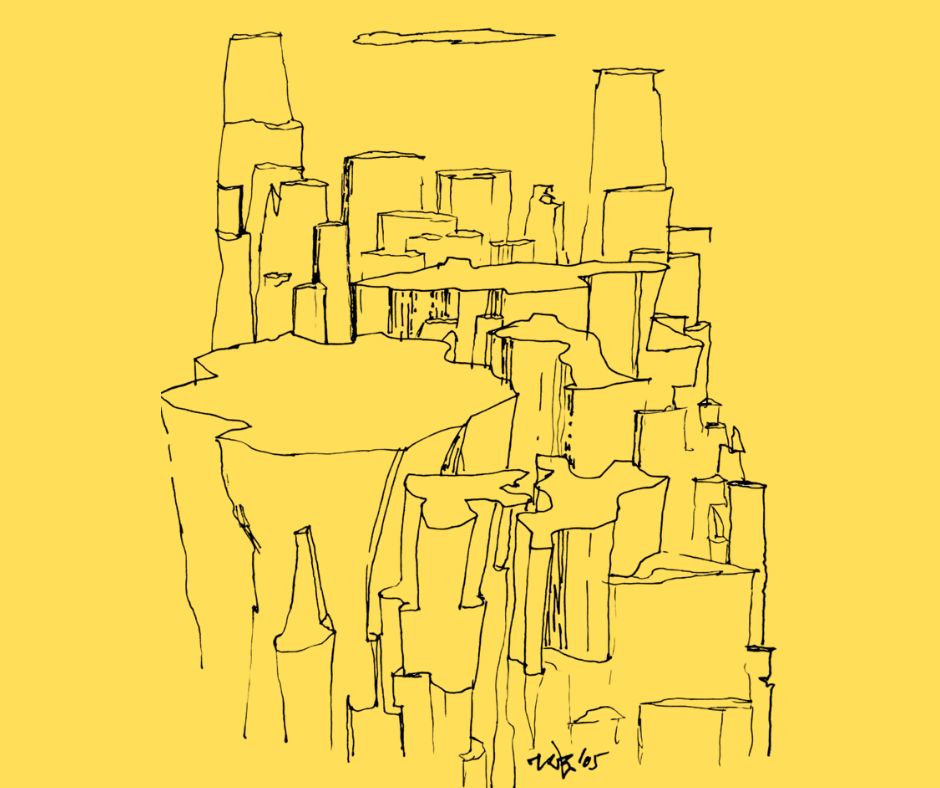

This took more time than anticipated. Many months passed by before I made my way through a wintry but sunny afternoon to Kashmiri Gate and got dropped in front of what used to be the Minerva Cinema. Weaving in and out of people, conversations, street dogs, the mixed smell of sweat, bidi smoke, burnt tea & grease – I gasped for any familiar landmarks. Meandering aimlessly, I looked at auto part shops transitioning into warehouses with paan stained walls. The skies darkened and a few drops started to trickle from the blue tarpaulin of the tea stalls. I somehow made my way out looking at the Google map and tried once again to orient myself.

Photo Credits: Ms Lucy Peck

I felt strange in a place which I thought would be most familiar to me. The visual cacophony made me close my eyes. It struck me that perhaps it would be best to use Ms Peck’s map which seemed more intuitive to follow. After locating Lal Masjid, I followed a narrow alley with small shops on one side and a boundary wall of a government building on the other. The rain was now pouring more heavily; From the corner of my eye, I saw what appeared to be the open phatak from Ms Peck’s photos. I leapt over potholes and dodged the incoming cyclists to take refuge under the arched vault of the phatak structure.

At the tea stall to my right, a few men were talking on the phone while others indulged in a smoke peacefully sitting on the otla. The building had indeed been repurposed and few fragments of its original structure remained. I walked around the structure taking photos but there was not much to see – I felt a heaviness coming over me and looked for a place to sit.

‘Photo kyun le rahe the?’ – enquired a burly person sitting next to me, his tone didn’t seem friendly. ‘MCD se ho kya?; yahan photo-voto lena allowed nahin hai’. I suddenly realised that I was being watched and despite the din of the market, I must have stuck out from the crowd as a stranger. I quickly gave a rambling explanation of my family’s connection to Kashmiri Gate and how I am visiting it after many decades. He listened intently with eyes darting towards me and our home as I explained the changes between the old structure and how it seemed now. Finally convinced, he slumped back onto his seat and beckoned me to join him. Waving away the rest of the people who had gathered, he asked the tea seller to get two cups of tea.

Handing me the small plastic cup, Altaf introduced himself – His family also had roots in the same neighbourhood. He was about the same age as me and proudly showed me the photo of his son and the rest of his family. He explained how they had earlier faced trouble with MCD and other authorities with the proliferation of all the commercial shops and dilapidating structures. The rain started to recede, and he looked up and asked me to follow him. Altaf took me to the alley on the right and asked me to wait inside a small shop. Soon, he brought in his elder brother Adeeb, who was able to remember our family from the past. They took me around the compound and showed me remnants of old staircases, boundary walls, and cracked pilasters which were supposed to be there for the last 40 years. Inside the shops, where there was the living room – The initial guarded conversation had now given way to a more laidback banter filled with nostalgia. Once again, the space transformed into what it always was – a majlis.

It was cold outside, but I barely noticed as I said goodbye to Altaf & Adeeb. Walking back, I looked again at the house; It seemed different now. Although the walls were crumbling, the people in it infused a life of their own into it. Every wall had a story, every brick had a life that passed through it.

In a moment of quiet reverie, my mind returned to Calvino again. In ‘Six memos for the next millennium’ (Calvino, Six memos for the next millennium 1988), Calvino evoked Boccacio’s Decameron with a particular passage on the Florentine poet- Guido Cavalcanti. When a crowd of peers metaphorically try to weigh down Guido walking alone in a cemetery of marble tombs; he cuts through by retorting –

“Gentlemen, you may say anything you wish to me in your own home” Then, resting his hand on one of the great tombs and being very nimble, he leapt over it and, landing on the other side, made off and rid himself of them.”

Photo by author

He states further-

“Were I to choose an auspicious image for the new millennium, I would choose that one: the sudden agile leap of the poet-philosopher who raises himself above the weight of the world, showing that with all his gravity he has the secret of lightness and that what many consider to be the vitality of the times—noisy, aggressive, revving and roaring—belongs to the realm of death, like a cemetery for rusty old cars”.

Through the journey of discovering the built form of the house, I had been accumulating the quiet weight of its history, its physical attributes, and its context for the rest of my childhood. I feared losing the richness of my memories in the beginning, but as I left Kashmiri Gate- I seemed to feel lighter, having found a small sip of my spiritual home in its twilight years.

Bibliography

Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich,, 1974.

—. Six memos for the next millennium. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 1988.

Peck, Lucy. Delhi, A Thousand Years of Building. INTACH Roli guide, 2005.

[1] https://rgplan.com/ncr.html

[2] For more on James Skinner, more can be found in the ‘Military memoir of Lietenant Colonel James Skinner C.B. by J. Baillie Fraser Esq. published in 1851 by Smith, Elder & Co., London

[3] For more Maps on Delhi, see the excellent hardcover ‘Maps of Delhi’ by Pilar Maria Guerrieri published in 2017 by Niyogi Books