Architectural Heritage in India: Conversations on Conservation, Preservation, Restoration series by ArchitectureLive! aims to shed light on the complex issues surrounding architectural heritage in India by drawing insights from a diverse array of experts, across India. It is also a way to throw light on the multifaceted challenges and emerging solutions in this critical domain. In the first of the series, we have a conversation with Dr. Shikha Jain.

Shikha begins the conversation with a detail on how DRONAH came into existence.

I was involved in regular practice and working with INTACH because of my interest in heritage, and my master’s degree focused on preservation too. After completing my PhD, I wanted to focus more on research than just working on conservation or architectural projects. I wanted to integrate a strong research component into my work. This led me to pursue teaching, but I felt the lack of research opportunities in the institutional environments in India.

I believe that in conservation, 70% of the effort is research and engaging with stakeholders before deciding on any intervention, which is only 30% of the remaining work.

That’s when I decided to start my own research-focused practice—and that’s when DRONAH emerged in 2003 and has been around for almost 20 years. The idea behind DRONAH was to be inclusive, not only focusing on cultural heritage but also on the environment and community. If you see the logo of DRONAH, you can see the built, the leaf, and a person representing the built heritage, the environment, and the community. DRONAH also stands for Development and Research Organization for Nature, Arts, and Heritage, to reflect our inclusive and multi-disciplinary approach. It aligns with our long-term vision for DRONAH to become an institution that focuses on teaching and training, besides research. Being registered in Gurgaon, it was appropriate to use the name DRONAH for this purpose as an acronym.

Rajesh Advani:

What were some of your initial projects at DRONAH when you started your work as a researcher?

Shikha Jain:

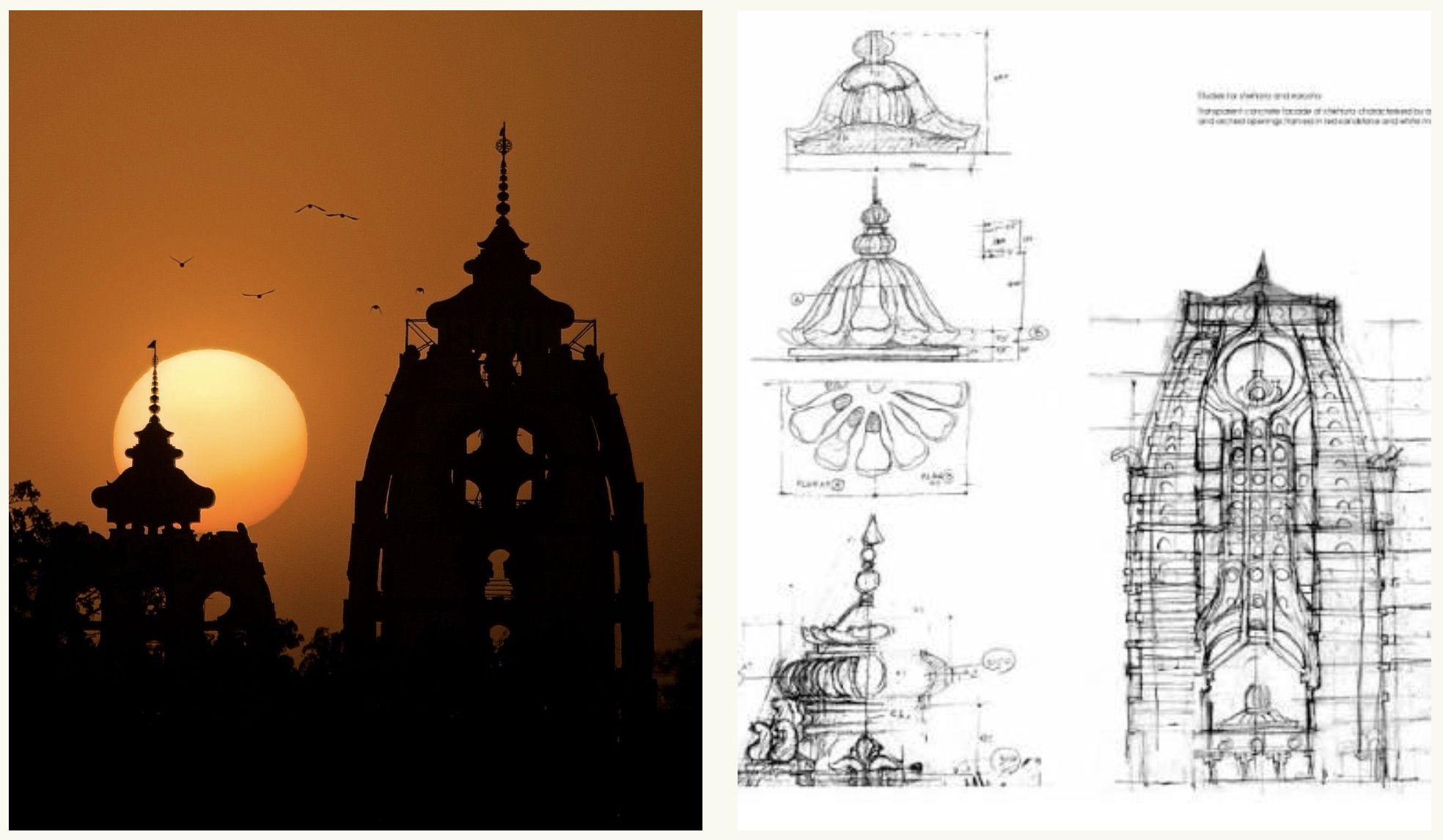

Our first, and still my favourite, is the City Palace Udaipur, which really launched DRONAH in 2004. We began working on it in 2004 with our client, Shriji Arvind Singh Mewar, under the Maharana of Mewar Charitable Foundation. It spanned 20 years, during which we developed the complete conservation master plan, seeking funds along the way. In 2004, he suggested that we apply for a conservation master plan grant from the Getty Foundation. We received the first Getty grant in 2005.

In most cases, government projects do not allow enough time for research and studies due to the pressure of completing the works in stipulated time frame for budget utilisation or inauguration purposes. So it was an opportunity to work on a project funded by the Getty Foundation that allocated time and budget for comprehensive documentation, in-depth surveys and interdisciplinary research.

In 2007, we developed a conservation master plan and conducted workshops to assess the condition of the site. We realised that more work was needed as, during the documentation process, we discovered 13 layers of historic fabric in the building and identified five major architectural styles associated with the 22 Maharanas who had occupied the building since the 16th century. The daily records called Bahidas of the Maharanas provided valuable information about the palace structure over time. The paintings also allowed us to track changes such as modifications of the dome and the addition of gates.

In India, there were no lidar survey tools for documenting heritage structures at the time. We collaborated with IIT Roorkee, where Dr. Kamal Jain led the photogrammetry of the entire façade. He even took station points on a moving boat to document the lakeside façade. This was a great achievement for us.

In 2009, we received another grant from the Getty Foundation to work in more detail on our research. We developed sub-plans under the conservation master plan and a universal access plan for the museum in collaboration with SPA Bhopal. We also received funding from the Ministry of Culture, which allowed us to execute some components, like the museum in the Zenana. In 2012, we received funding from the Ministry of Culture for the museum grant, enabling us to work on some of the galleries. We also worked on Udaipur’s forts, such as Kumbhalgarh and Chittorgarh, which we helped place on the World Heritage List. I worked on the architectural guide published in 2021, and our work on the City Palace Museum was published by Mapin in 2017 and well appreciated by the Getty Foundation.

The other thing was our publication called “Context.” It started as a biannual refereed journal and later became an annual publication. Our inaugural product from 2003 to 2004 was the first issue, when there were no journals on heritage in India. I was keen on publishing regional research or research that wasn’t available to the public.

Rajesh Advani:

Over the years, you have worked with many organisations like INTACH, UNESCO, the Getty, and institutions like SPA, focusing on restoring or preserving heritage sites. What are the main challenges you’ve encountered [working with these organisations] in restoring or preserving these sites?

Shikha Jain:

There are a lot of challenges that vary depending on the client, project, site, and context. Around 90% of heritage properties in India are government-owned. So, when it comes to them, they have set ways of doing things, such as tenders, RFPs, etc. When conservation architects entered the scene in India around 2004–2005, they were not involved in government projects. The situation has changed now, but the documents, like RFPs, are still prepared by engineers who lack conservation knowledge.

The question then is how do you introduce new innovative ideas? How do you include certain aspects of conservation which were never there?

Another challenge is the enforcement of legislation. Management plans for World Heritage sites often remain stagnant after being prepared, as the government officers lack the knowledge to execute them. The practice in India is a traditional practice of being more action-oriented rather than document/planning-based. So, added challenges in this field are the enforcement of the legislation, making plans understandable and executable on-site, finding skilled labour who understands heritage, ensuring material availability, and engaging good contractors who understand conservation.

Fortunately, the Rajasthan government was the first to create a schedule of rates for archaeology in 1995. The schedule includes rates for various tasks, such as creating elements like Jharokas, Goombads, and Chhatris in different places, and covers the costs of materials like stone and lime mortar. When the Rajasthan government took up the Amer project, they introduced a clause allowing for a 50% variation in costs for conservation projects due to the uncertainty of the condition of old buildings, which is often revealed onsite when work starts. This flexibility enabled more efficient conservation projects.

Although the situation in Rajasthan has changed, I saw the impact of their approach spreading to Punjab as well. During the 13th Finance Commission project for Punjab, we found that the contractors, both local to Punjab and those from Rajasthan who were familiar with the process, were not adequately equipped to handle large-scale projects in Punjab effectively. We had to source craftspeople from Rajasthan for specific craftworks like stone carving.

Similarly, we hired craftspeople from Rajasthan for the restoration of the Golden Temple, given to us by SGPC, as craftspeople from Punjab have skills for works like gilding rather than wall paintings. But there always was an exchange of craftsmanship between regions like Rajasthan and Punjab, even historically—during the time of Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Rajesh Advani:

You mentioned that 90% of this work is in the public domain, owned by the government. But it is accessible to not just the government but also to people from diverse backgrounds who have their own interpretations. Is it a challenge to create something accessible to everyone so that they understand the importance of conservation of the structure?

Shikha Jain:

I want to address the conservation component before coming for the interpretation. It’s important to ensure that property owners or patrons understand how to care for their property in the long term. We have encountered instances where clients are keen on understanding the significance of the structure. That is what conservation architects do: establish its significance and protect it. We do it by understanding the values of the structure, such as historic, architectural, and environmental values, which influence the conservation plans. Then comes authenticity—what needs to be protected and preserved without change; how much of it is retained. We make decisions about what can be changed and what should be conserved. We utilised adaptive reuse in the City Palace and Gandhi Bhavan projects, to explain to stakeholders why certain changes can be made in some areas but not in others.

Sometimes, stakeholders are unaware of the damage they are causing. For example, at the Golden Temple, the washing of the floor with milk is part of the ritual. But it is also damaging to the marble in the long term because of lactic acid. We explained this to the stakeholders, but they informed us that since it is a ritual, some things cannot be changed, yet for us, it’s important to create awareness.

What we need to do when we are working on conservation projects—keep them inclusive, and have onsite demonstration workshops allowing people to come and learn about traditional techniques that are cost-effective and better for their buildings, especially involve those who own such structures.

Rajesh Advani:

You also have a book, Incredible Treasures: World Heritage Sites of India. What inspired this publication, and what kind of impact do you hope it will have on readers?

Shikha Jain:

I think this book was long overdue.

I was actively involved with the Ministry of Culture and ASI from 2012 to 2015, during which I was also a part of the World Heritage Committee meetings. I witnessed firsthand how other countries showcased their heritage sites. Since India had no single publication on its world heritage sites, we felt the lack of such a book.

The book was completed in 2021, thanks to Mr. Eric Falt, the UNESCO New Delhi director at that time. Mapin, an internationally known publisher, came on board after being evaluated by UNESCO, New Delhi.

It is very basic as it introduces one to all of India’s World Heritage Sites. My mentor, the late Mr. Vinay Sheel Oberoi, was my co-editor. His target was to make it understandable to a layperson, so the book is not very technical. There are 500-word articles on each site that discuss their unique aspects with details or anecdotes that are not found in the official UNESCO dossiers. We received contributions from well-recognised authors like Amita Baig, Janhwij Sharma, Dr. Sonali Ghosh, and Dr. V.B. Mathur.

Mr. Eric Falt also emphasised that the publication should be visually impressive, so we had to ensure that the photography was of excellent quality. That is why the photographer Rohit Chawla is credited besides the editors on the book cover. The impact of the book is greatly enhanced by the photographs of the World Heritage Sites. They truly capture the unique value because of which the sites were inscribed on the list.

Rajesh Advani:

DRONAH has handled different kinds of projects in Jaipur and Ajmer [Revitalisation of Ghat ki Guni and HRIDAY projects]. Can you share the innovative strategies that became part of these projects?

Shikha Jain:

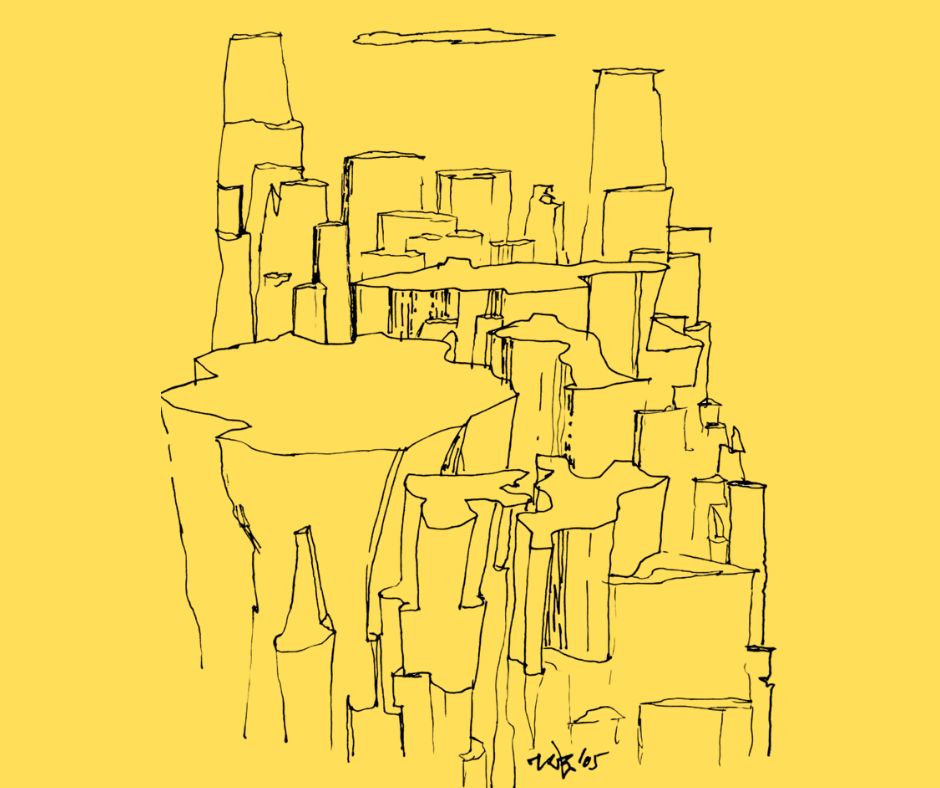

The Ghat ki Guni site holds a special place in my heart, as it was the subject of my undergraduate thesis. It has 52 heritage structures spread across the valley, on the outskirts of Jaipur. After completing my bachelor’s and master’s degrees, I continued to work on this project, even participating in a competition organised by the Rajasthan Tourism Department, where I was fortunate to be among the award winners.

A few years later, there was a proposal to redirect the traffic from the valley’s highway to a tunnel. It was a major project that required environmental clearance and the construction of the tunnel. Because of my knowledge about the site, I was involved in it. Parallelly, I also realised that these 52 structures were unprotected. I reached out to Mr. Salahudin Ahmed, heading the archaeology department as the principal secretary, who was equally passionate about heritage. Thanks to his immediate action and support, all 52 structures and the entire Ghat ki Guni were legally protected under archaeology. The project was revised multiple times; in 2010, the tunnel was finally completed.

With the area now free, the Jaipur Development Authority requested a new proposal. It was one of the first urban-heritage acupuncture projects in Rajasthan, particularly for a heritage site of that level. We conducted interviews with the private owners to get NOCs from them for the work on the façade conservation.

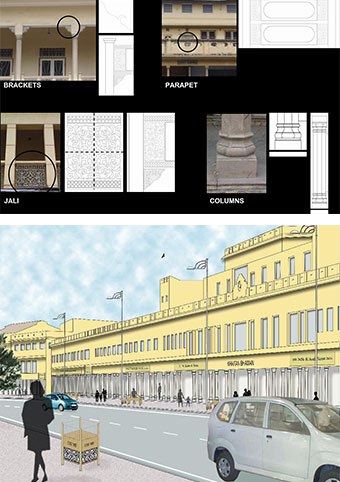

We followed the same approach for three bazaars in Jaipur in 2011–13. It was the first time that government funding was used to conserve the façade of privately owned historic areas under JnNURN. The need for government funding to conserve private houses in Jaipur was questioned. So, we gave them the Nigam Act, which mandated the conservation of the city’s pink façades.

The same clause was used for the HRIDAY project, under MoHUA, where 12 cities required conservation consultants to identify heritage walks and façade conservation initiatives. DRONAH was the HRIDAY City Anchor for Ajmer and Pushkar. We used the example of Jaipur’s conservation project to justify government funding for other urban conservation projects. That made it easier for the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development to take a call. That is how the projects and their impacts get linked.

Rajesh Advani:

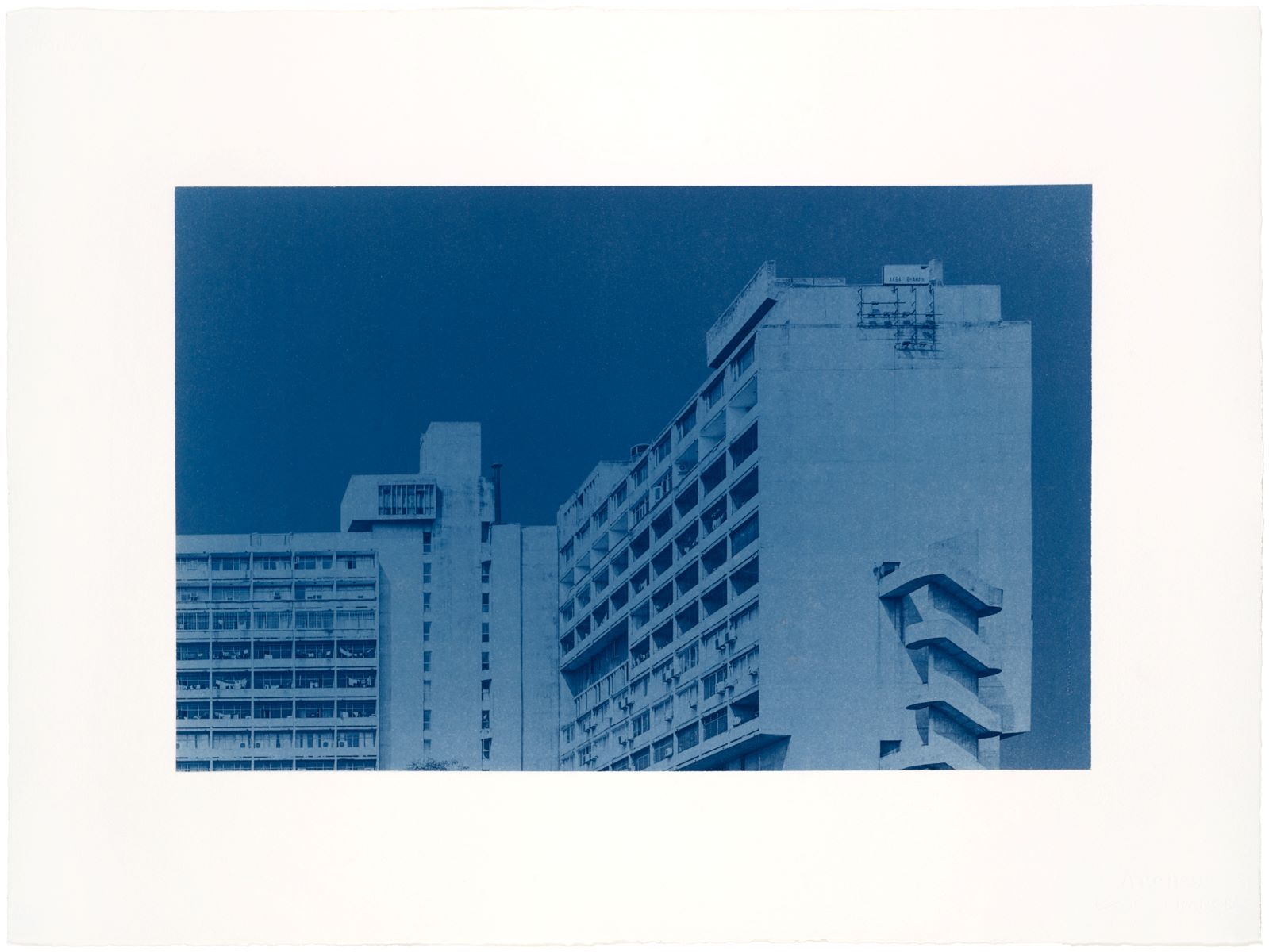

When we discuss heritage, we focus on the age of the building, but there is a growing debate around preserving modern heritage, which may not be very old, like Kala Akademy in Goa or the Sardar Vallabhai Patel Stadium. With no legal framework currently in place, where do you think we are headed?

Shikha Jain:

To say that there is no existing legal framework for modern heritage is wrong because Chandigarh and Bhubaneshwar have it. As we have worked in Chandigarh, we know that the city has a well-articulated Master Plan by Sumit Kaur [the then Chief Architect]. The master plan has included all the graded buildings, like the Gandhi Bhawan [Grade 1 structure]. Any changes to it, require approval from the Heritage Committee. You can find it in Bhubaneshwar too, where Sanghamitra Basu tried to integrate the heritage structures in the master plan, but she can provide more information about that.

These two cities are concentrated with modern heritage. Even the locals, who are not architects, are passionate about the heritage.

Rajesh Advani:

What is your view on the government’s decision to use the building’s age as a criterion for not granting the Hall of Nations heritage status when it was demolished?

Shikha Jain:

That’s the problem with the British Period Acts, currently adopted by ASI and other archaeology departments, which consider heritage based on the age of the structure. However, conservation architects assess the significance based on values like architectural, environmental, historical, and cultural. I believe that the number of years a building has stood for cannot be the only way to assess its heritage value.

In the Hall of Nations, we failed because it was only valued by architects and not by the larger community, particularly the people of Delhi. That’s what you need for protecting heritage.

As the interview reaches the end, Shikha focuses on the importance of raising awareness among students about architectural heritage and incorporating it into the architectural curriculum.

Dr. Shikha Jain

Dr. Shikha Jain is an architect with an extensive portfolio on cultural heritage, covering Conservation, World Heritage, and Museum Planning of over 75 plus projects in India and overseas, largely through her organisation DRONAH. As an international expert, she has advised government organisations and UNESCO offices in several countries. She has represented the Ministry of Culture, India on the UNESCO World Heritage Committee and served as a bureau member for the 45th session in 2023. Her work includes preparing dossiers for Indian World Heritage sites, designing museums and interpretation centres, and leading urban conservation projects that have received national awards and international awards. Dr. Jain is a graduate of SPA Delhi and Kansas State University, U.S.A., with a doctorate from De Montfort University, U.K. She is actively involved in training programs, academic institutions, and professional organizations related to cultural heritage. She is involved in training programmes for the UNESCO C2C at WII, Dehradun, is an Adjunct Faculty at the Manipal University Jaipur and is the State Convener for the INTACH Haryana Chapter. She is also Vice President, ICOFORT, ICOMOS, the international advisory body to UNESCO.

Credits:

Transcribing and Editing: Geethu Gangadhar