Architectural education in India has long been perceived as a prestigious and intellectually demanding pursuit. However, beneath its façade lies a deep-seated inequality that dictates access, quality, and opportunities for aspiring architects. This research investigates the structural disparities within architectural education across government and private institutions, exploring how financial constraints, faculty quality, curriculum design, and technological accessibility shape student experiences.

A Systemic Divide

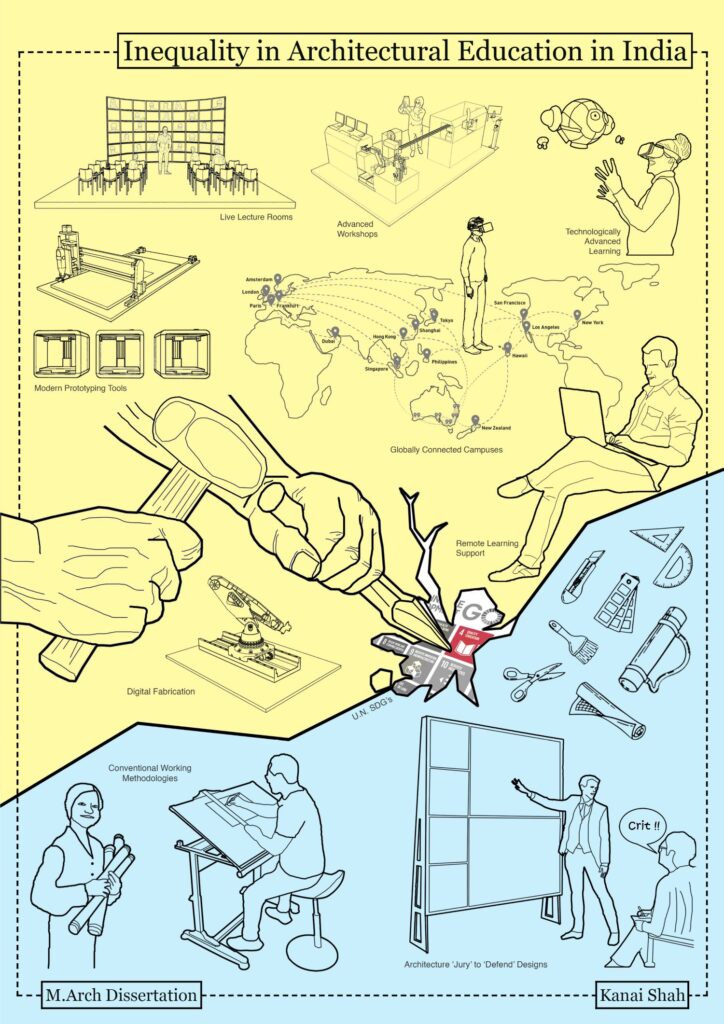

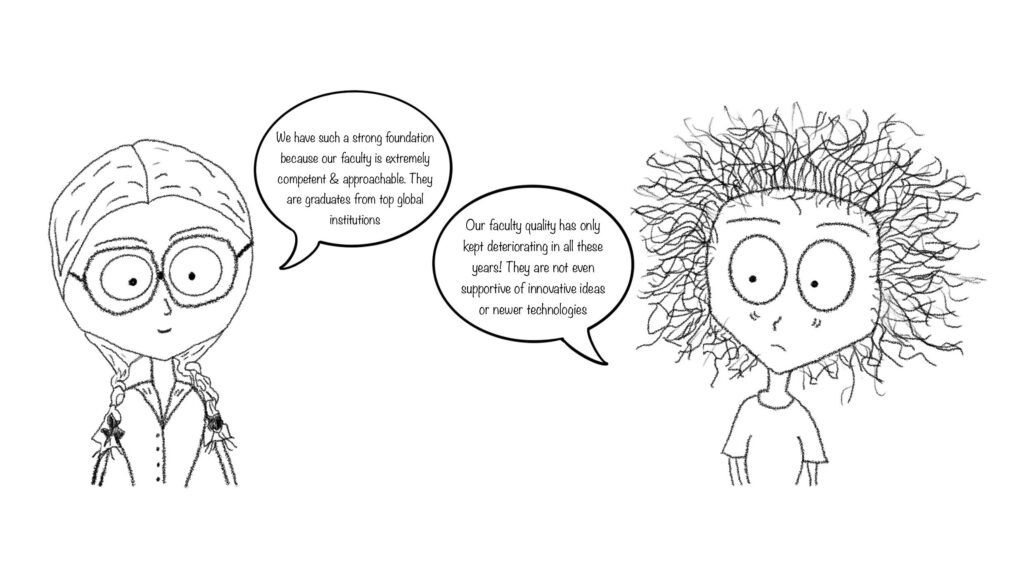

The study reveals a stark contrast between elite private institutions and resource-constrained government colleges. The rise of private institutions has introduced global teaching methodologies, cutting-edge infrastructure, and internationally trained faculty. However, these advantages come at an exorbitant cost, making quality education inaccessible to a large section of students. On the other hand, government institutions, despite offering lower tuition fees, often lack experienced faculty, practical exposure, and access to evolving technologies, creating a significant skills gap among graduates.

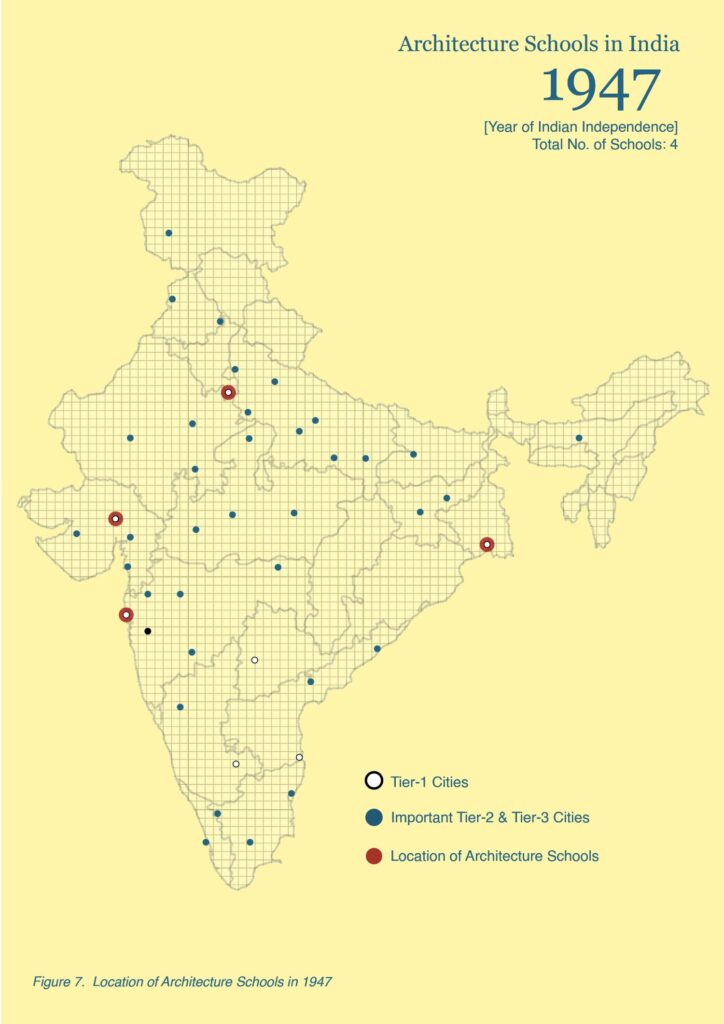

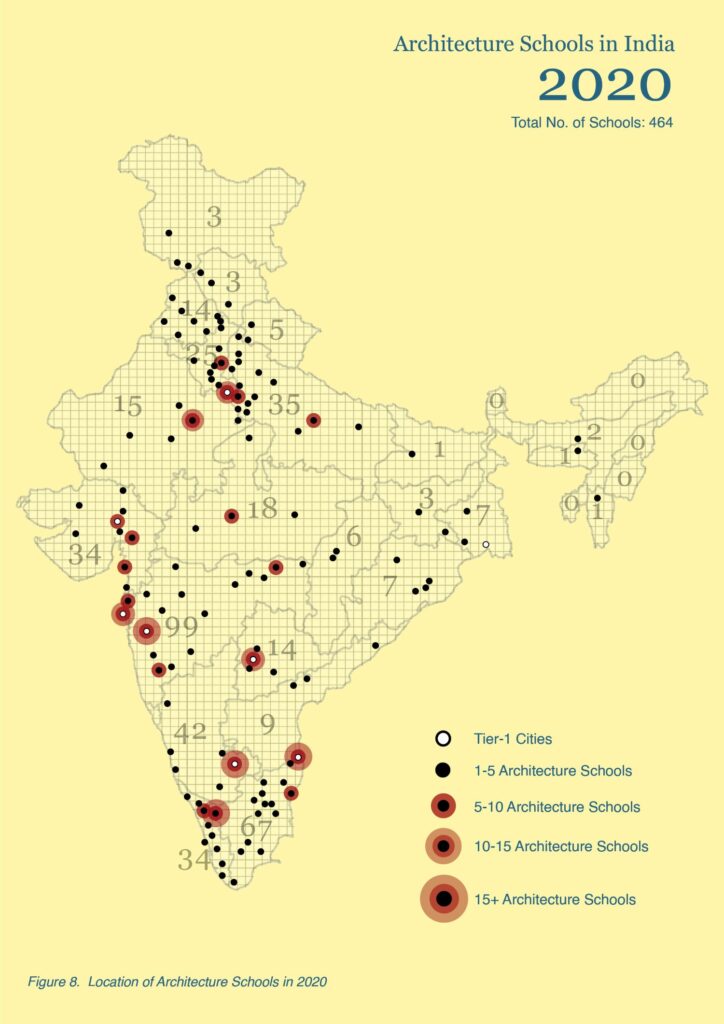

One of the most pressing issues is the unregulated expansion of architecture schools across India. Over the past two decades, the number of architectural institutions has surged, often without maintaining minimum educational standards. Many of these newly established schools are driven by commercial interests rather than a commitment to academic excellence, leading to a “quantity over quality” crisis. The lack of trained educators has further widened this disparity, with elite institutions attracting the best faculty while others struggle with unqualified or disengaged teachers.

Curriculum and Learning Gaps

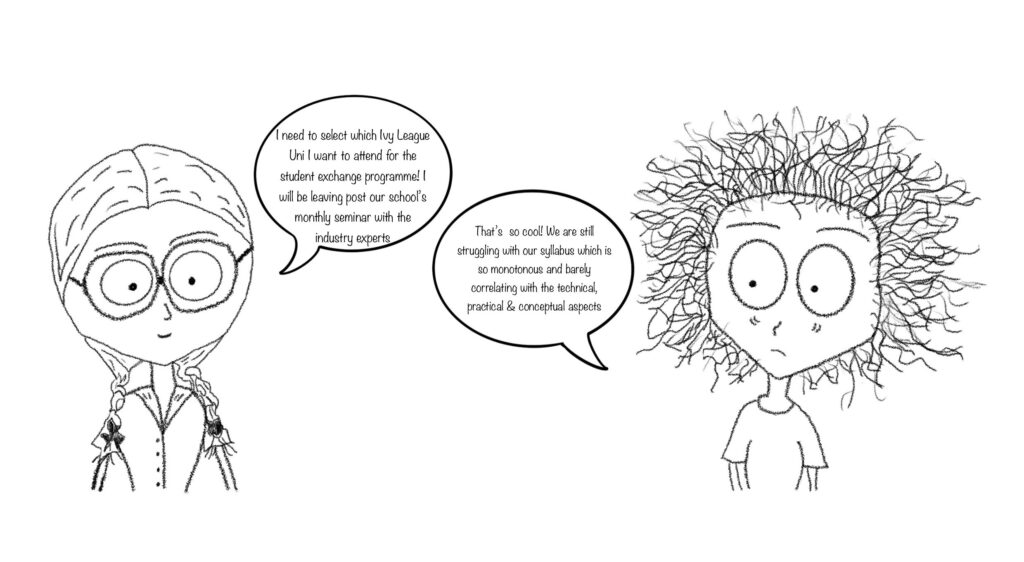

Beyond faculty and infrastructure, curriculum inconsistencies significantly impact educational quality. Private institutions often introduce progressive, research-driven, and interdisciplinary approaches to design, while many government colleges continue to follow outdated syllabi, emphasizing rote learning over critical thinking and innovation. Additionally, the integration of practical training, international collaborations, and multidisciplinary exposure remains highly uneven.

A key finding of the research highlights the limited access to advanced technology in many institutions. As architecture evolves with digital modelling, parametric design, and AI-driven tools, the disparity in technological exposure is creating an uneven playing field for graduates. Private institutions can afford cutting-edge computational design labs, while many government institutions lack even basic digital resources. This technological divide extends beyond education, impacting employment prospects and future career growth.

Financial Barriers and Institutional Policies

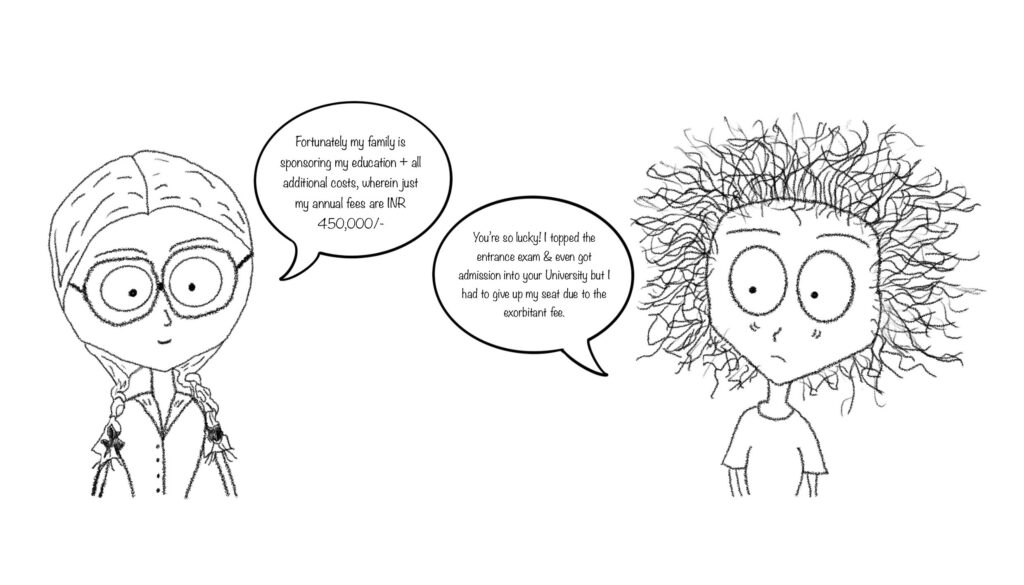

The cost of education in private institutions is often prohibitively high, with tuition fees ranging from INR 1,10,000 to INR 6,00,000 annually. In contrast, government institutions charge significantly lower fees but fail to provide quality education, forcing students to invest in external training programs, workshops, and software courses to bridge their skill gaps. The absence of adequate scholarship programs, transparent admission policies, and standardized faculty screening processes further exacerbates these inequalities.

Additionally, the prevalence of the quota system and management seats in several institutions distorts the merit-based selection process. The study finds that while some students benefit from reservation policies, the overall impact on educational quality remains questionable due to inconsistencies in faculty competence and institutional funding.

Impact on Career Trajectories

The inequalities in education directly translate to disparities in career opportunities. Graduates from top-tier institutions secure placements with leading architectural firms, leveraging their exposure to international design competitions, interdisciplinary collaborations, and cutting-edge technology. Meanwhile, graduates from lesser-known institutions struggle to compete, often facing lower salary packages, fewer internship opportunities, and limited access to professional networks.

A major concern raised by the research is the exploitative nature of architectural internships in India. Many students, particularly those from underprivileged backgrounds, are forced to accept unpaid or low-paying internships due to a lack of structured regulations. Some firms even charge students for internships, further deepening the financial burden. Without proper compensation and learning opportunities, many graduates enter the workforce underprepared and undervalued.

Proposed Reforms and Future Outlook

To address these disparities, the research suggests several policy interventions and structural reforms:

- Decoupling Educational Regulation from Licensing:

The Council of Architecture (COA) currently oversees both education and professional licensing. Separating these functions could create a focused and independent regulatory body dedicated to raising academic standards. - Excellence Clusters for Knowledge Sharing:

Establishing regional mentorship models where elite institutions guide under-resourced colleges can foster collaborative learning and equitable access to knowledge. - Standardized Curriculum and Digital Integration:

A nationwide curriculum revamp focusing on technology-driven learning, hands-on practical training, and sustainability is crucial. Encouraging institutions to integrate e-learning platforms like Coursera, ACEDGE, and edX can bridge digital divides. - Fair Internship and Employment Policies:

Implementing minimum wage mandates for internships, similar to RIBA’s chartered practice policies, will ensure students gain valuable, compensated experience. - Transparency in Faculty Recruitment and Institutional Performance:

Publishing faculty credentials, institutional accreditation reports, and student outcomes can foster accountability and help students make informed decisions. - Affordable and Inclusive Education:

Expanding scholarship programs, low-interest education loans, and government funding can make quality education accessible to a broader demographic.

Conclusion

Architectural education in India is at a critical crossroads, where unchecked expansion, financial barriers, and technological gaps threaten the future of aspiring architects. By implementing holistic reforms and fostering collaboration between institutions, policymakers, and industry stakeholders, India can bridge these educational divides.

The goal is not just to educate architects but to empower them—ensuring that talent, rather than privilege, defines the future of the profession.