Those wondering why the design of contemporary Indian cities is such an arduous and joyless affair will find Ranjit Sabikhi’s book of immense interest. Many may even find themselves jolted to action within their spheres of influence despite the book’s unflappable tone. Most importantly, this book is an invitation to liberate oneself from the valorised image of western or imperial city planning towards a more nuanced, indigenous, and flexible approach to our cities.

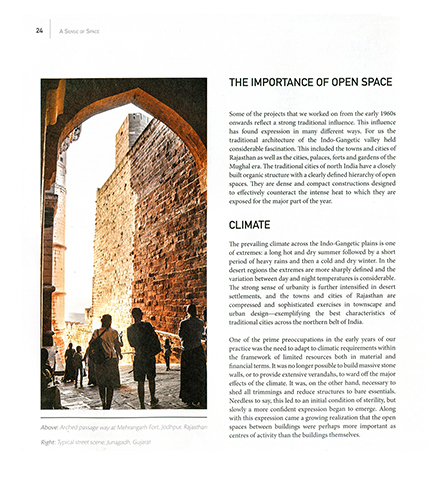

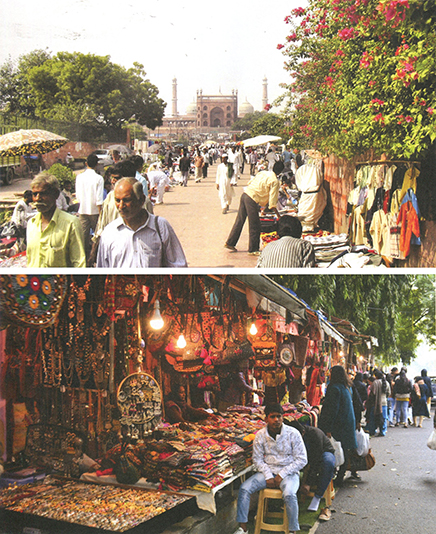

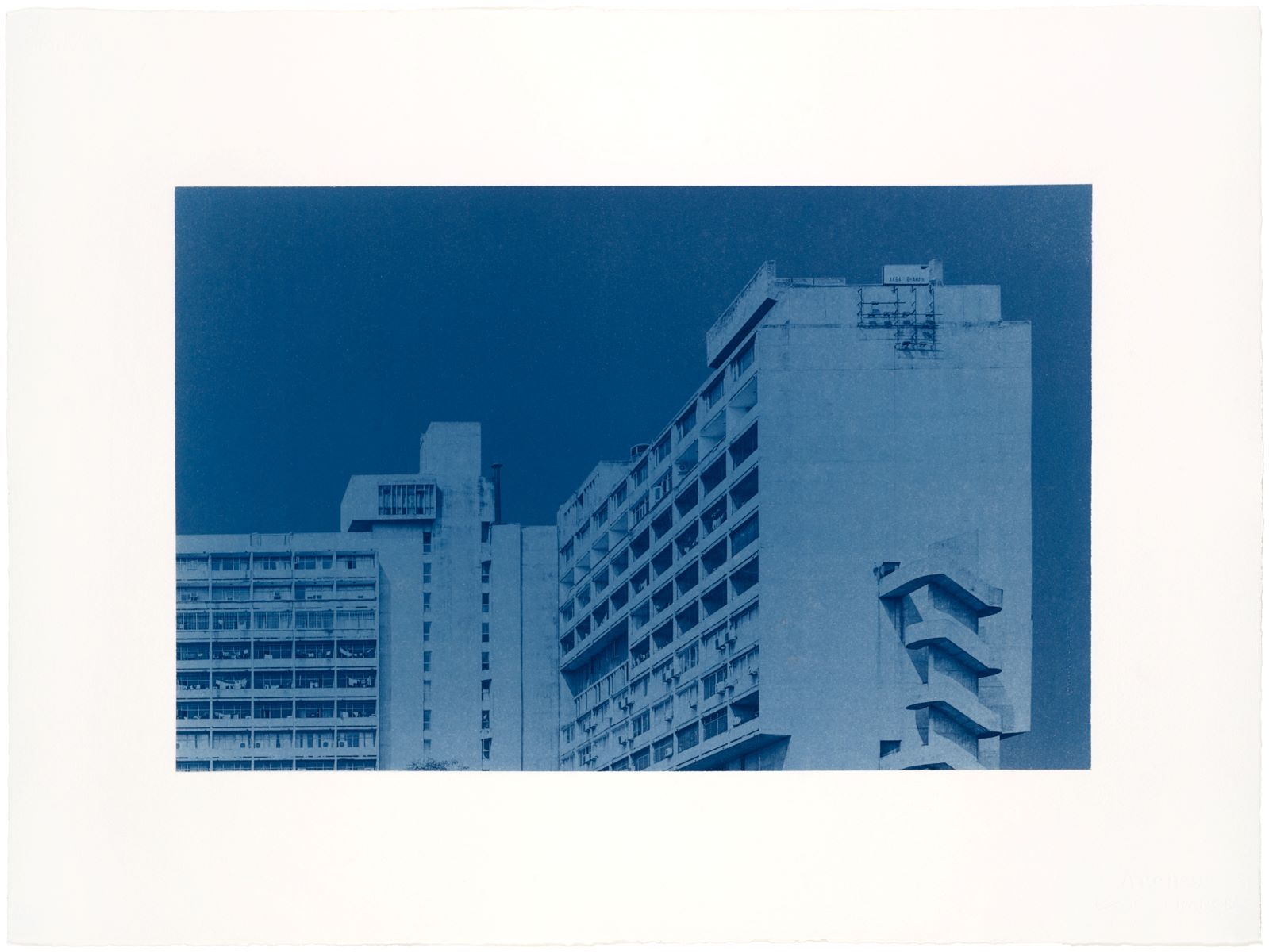

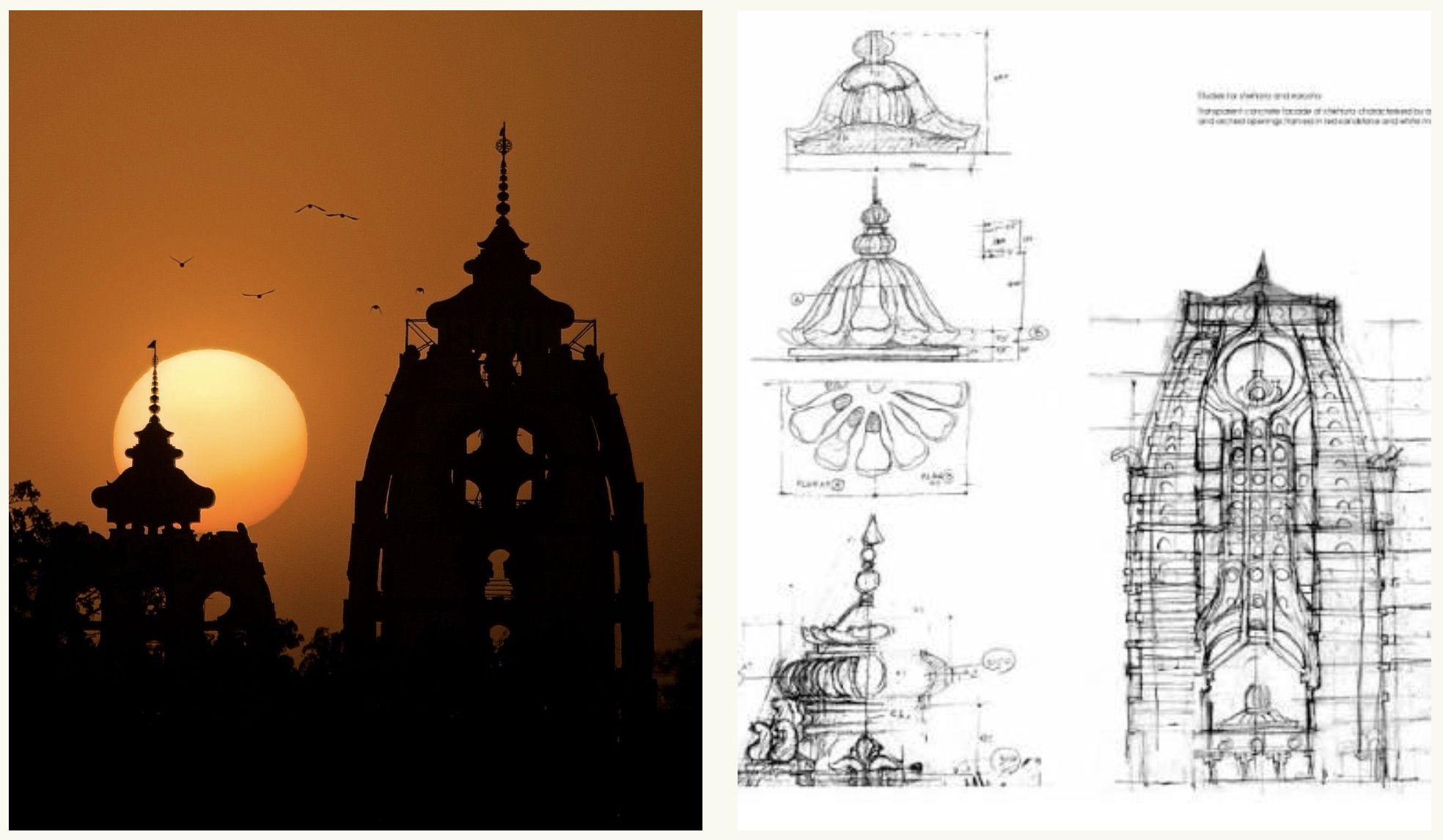

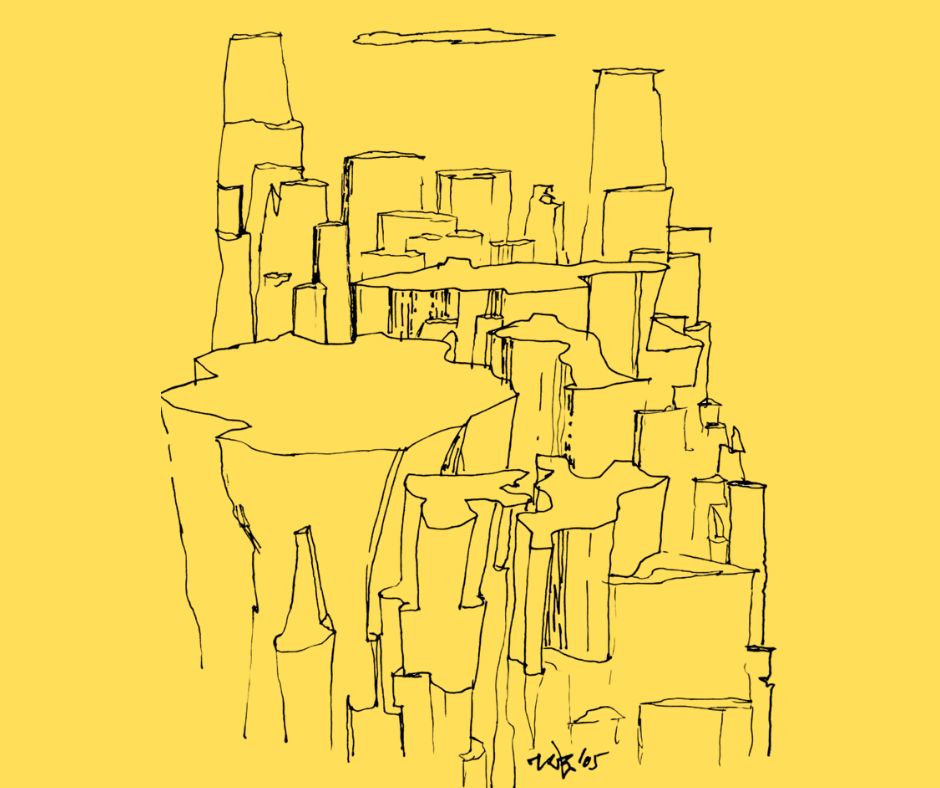

The hardcover, in the guise of a coffee-table book, contains well-illustrated and provocative sections that do not require a cover-to-cover itinerary. This particular format is usually reserved for subjects that are photogenic or pictorially arresting. Our cities in the years following independence have been far from the visually iconic settlements of the western world such as Paris or New York. The efforts of planners and urban designers in the country have been tentative and often obdurate since then, choosing to replicate the ‘cantonment-civil lines’ planning method of the British for expanding older settlements. Recently, efforts to bring our cities up to ‘world-class’ standards have invariably sought ideas situated in technology and the internet-of-things rather than founding them on a critical appraisal of past errors. The visual support to the text in this book is neither towards such gleaming ideas of future cities nor romantic sunset shots of Rajasthani forts. Rather, it is towards reinforcing a more vital “sense of place” that older Indian cities organically had but the newer ones severely lack. With recent public interest in smart cities and capital cities in India, this book is a timely and significant addition to concerns being raised from various quarters across the country towards feverish activity fuelled by federal budget allocations and an election-to-election activity cycle. The city-building maelstrom is in stark contrast to the struggles of professional planners and architects of this country over the past seven decades in their search for a meaningful, indigenous response to a unique set of challenges to which this book also bears witness.

I received my signed copy from the author a year back while he addressed a small gathering in the hope that the next generation will be better equipped with the knowledge of past successes and failures. Professor Ranjit Sabikhi—a well-known name in academia having headed the Urban Design department at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi in the 70s—is equally prominent in professional circles with scores of remarkable projects under his belt. This last idiom of having something “under one’s belt” could have been better framed even as this eighteenth-century reference to consumption is perhaps at the heart of issues concerning city-design today. The monetisation of land has become the central strategy for municipal and development authorities in the capital for some time now. A line from the present prime minister’s early speeches to foreign investors, “the government has no business being in business” may be rephrased more pertinently as “the government’s business is (also) to look after those who are not in business”. As the problems of the urban poor go unnoticed in masterplans, the cost of land does not allow planners to provide for open spaces in low-income areas. Sixty percent of Delhi, living in dwellings that are 250 square feet or less, find sustenance in the few remaining city-level greens. These too have been vulnerable to the political machinations of governments keen to leave their mark upon public land of which they are temporary custodians.

The book’s narrative starting from a general discussion of pre and post-independence town planning and design in the country quickly settles into issues that are specific to Delhi and its urban areas. Short yet insightful analyses of areas such as Connaught Place, Nehru Place, Delhi’s bazaars and malls, the issues around transit-oriented-development, urban villages and farmhouses etc. occupy a significant section of the book. These are interspersed by projects undertaken by the author’s firm that provide an interesting interlude while situating the concerns more tangibly for students of architecture and urban design. One wonders if this most unusual volume—a cross between an academic report, a monograph, and personal memoir packaged as a large colourful coffee table edition—may just be the catalyst required to turn jaded living room conversations into life’s missions.

Throughout the book are reminders of the power of places, positive or otherwise, alongside man’s inextricable bonds with the soil. Traditional urban spaces of Jaisalmer, Sikri, Padmanabhapuram, among others, were the only references for young professionals during the decades following independence. These became beacons amidst a lack of faith shown by the political leadership in the abilities of the country’s own design professionals. During such times the only ways of thinking about the city were either British cantonment planning, or in the wake of Chandigarh, a universalist vision of one-solution-fits-all. Sabikhi implores sensitivity to diversity, and more importantly, a diversity of response to the needs of the nation. As victims of modernity’s biggest affliction: the banality of uniform curriculum in education, a generation of modern planners and designers feel inured to the uncaring march of ‘development’. The villager undervalues his mud hut—inarguably the most relevant technology to save a dying planet—while cities grow uncontrollably in the image of places distant and foreign.

Despite the grimness of the circumstances around the design of cities in India, the book remains about hope. Pro-bono studies by the author of areas such as Khan Market and Greater Kailash M- Block Market carry the inherent optimism of design at the centre of change. The possibility of individual architects and urban designers to work within broad and often unidimensional brush strokes of planners is demonstrated here. Using the National Urban Policy Framework (2018) as a positive starting point for the proposed Delhi Master Plan 2041, Sabikhi suggests an intense and sustained planning effort that considers the views of the public before finalising masterplan content.

In the past, we have seen the emergence of new types of media such as blogs and podcasts that have enriched audience engagement by ‘unyoking’ from the rules that governed traditional formats. This book is particularly important, in a similar way, in becoming a conduit linking planning, urban design, and architecture that then leads to practice, research, and activism. With increasing awareness and the use of technology in planning and simulation-based design visualisation, a growing community of design and planning professionals may indeed activate a much-needed process of change. When they do, they will have the guidance of this valuable volume embodying the wisdom of decades.

About the book:

Author: Ranjit Sabikhi

Publisher: Harper Collins Publishers, India, 2019

262 pages, illustrated.

Rs. 1499 (hardcover)

Sudipto Ghosh is a practising architect in New Delhi. He is also visiting faculty at the School of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi.