Ranjit Sabikhi, the author of the book, A Sense of Space, The Crisis of Urban Design in India, belongs to that generation of architects and urban designers who have witnessed the transformation of the Indian city from the years immediately after Independence to the mega-metropolis that we now inhabit. In New Delhi, his city of residence for the last six decades, Sabikhi has, through both the written word and the built work, drawn from and commented on, the complexity of India’s historical and contemporary urban agglomerations.

While the duality of being both a consumer and producer of architectural and urban space would qualify him as an insightful commentator on the development of Indian cities, his book too both aligns itself with monographs that are often published on the works of architects and distinguishes itself from them in both its content and structure.

At the outset, A Sense of Space, The Crisis of Urban Design in India is a book about key issues of urban design and development as they relate to Delhi. Key ideas in the book are illustrated through examples drawn from both historical structures in the sub-continent and from the architects’ own portfolio of projects.

Bracketed by an introduction and a conclusion, that set the pace and lay the groundwork for his arguments, it ends by means of making definitive recommendations and comments. The text is otherwise structured around the six themes of land, space in the Indian context, explorations in urban design, Delhi’s changing profile, Delhi’s specific issues and urban crisis.

The book begins by looking at the past as a means of informing the practice of the present. On reminiscing about the “loss of local culture in favor of a uniform set of values”, Sabikhi draws our attention to the loss of cultural diversity as witnessed in the land and the ecosystems that it supports in favor of providing “equal opportunity and services to all.”

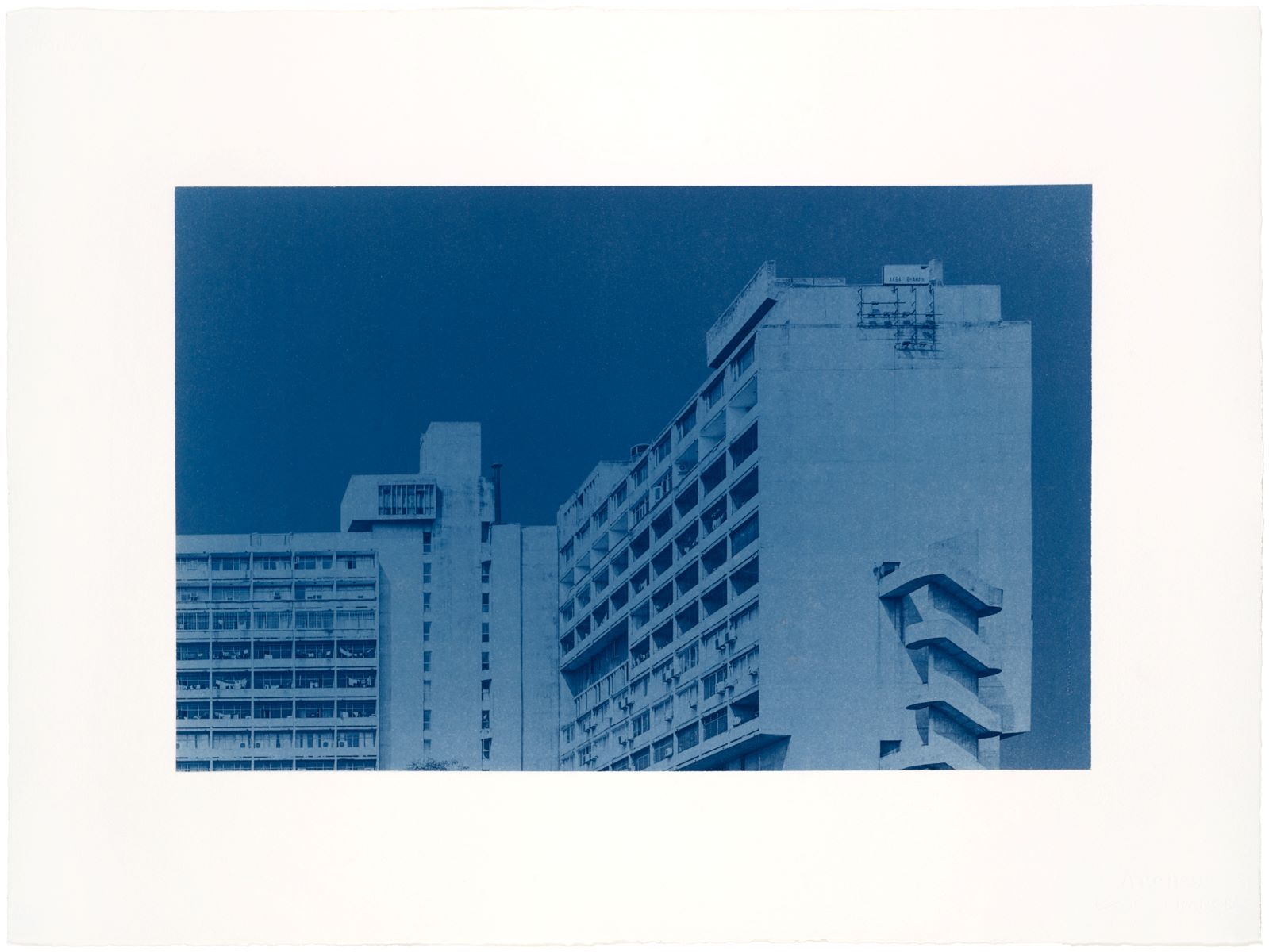

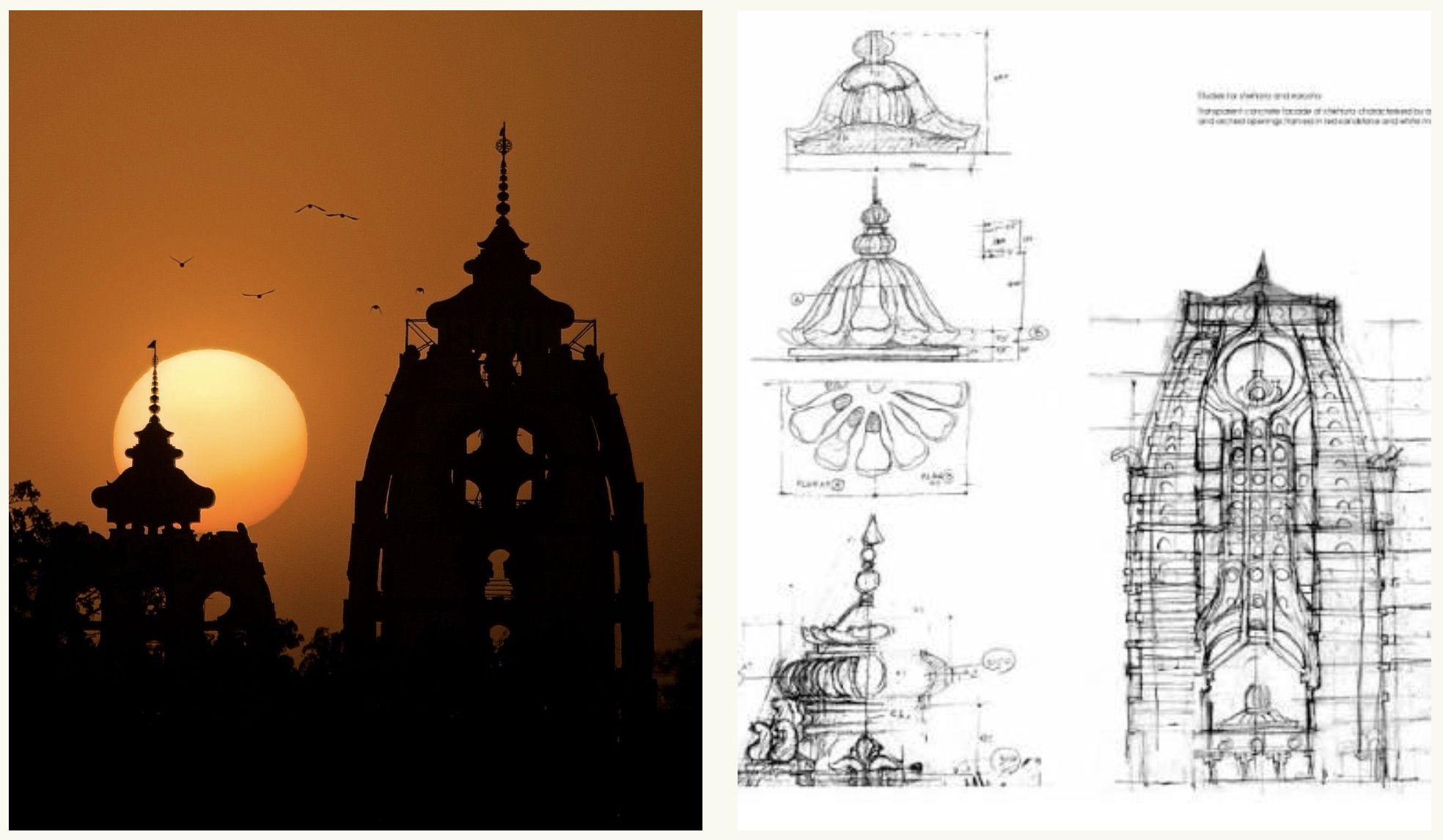

The two chapters, Space in the Indian Context and Explorations in Urban Design were a delight to read. The lucid text was supported by photographs and drawings of projects as diverse as the Yamuna Apartments Housing Scheme in New Delhi (1973) and the Mughal Sheraton Hotel in Agra (1974), both from the architect’s own portfolio. These buildings were juxtaposed with examples ranging from historical structures and projects such as the Surya Kund at the Sun Temple, the Modhera Complex, Datia and Amber Forts, the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai to relatively more contemporaneous projects like colonial New Delhi and post-colonial Chandigarh.

Meenakshi temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu. Photo: Bernard Gagnon/CC BY-SA 3.0/Wikimedia Commons

The text in these chapters illustrates not only the principles of urban design and planning but also their adaptation for a country that in the years immediately following Independence in 1947 had very limited financial resources. Sabikhi importantly also establishes the much-contested binary of western versus eastern ideas of urban design, the homogenizing effects of industrialization and the newfound reality that architecture has become a response to the rhythms of the real estate market that are at the best of times only “somewhat guided by developmental controls”.