JN Tata Auditorium

Indian Institute of Science

Bangalore | February 22, 2024

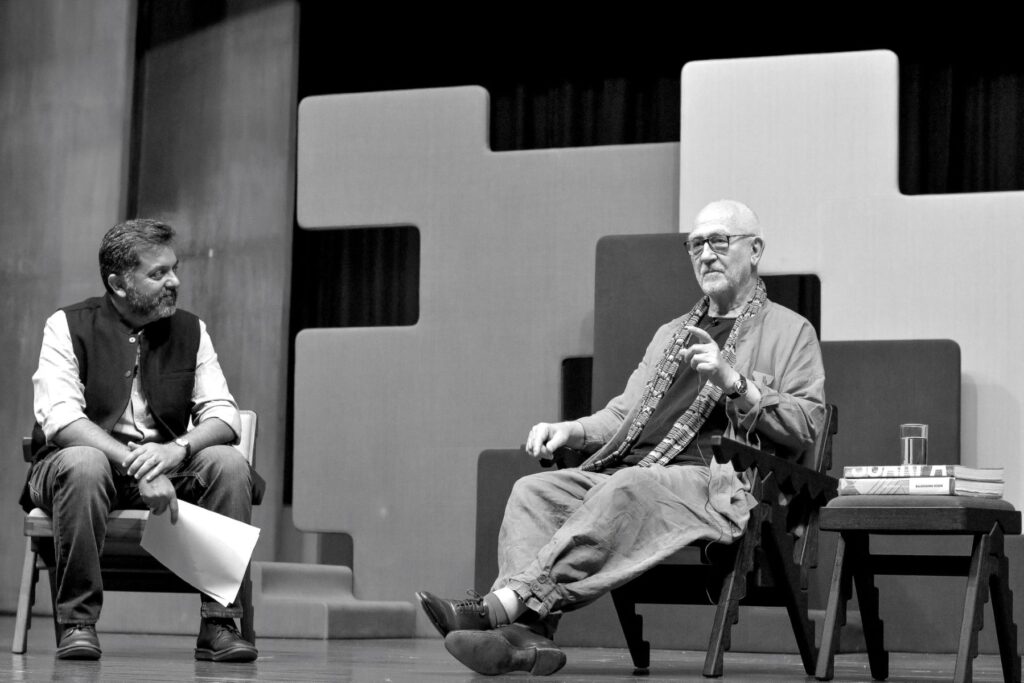

Swissnex in India, in collaboration with SwitzerlandIndia75, hosted the two renowned architects to discuss bilateral perspectives on architecture in an open format. This was a rare opportunity for architects and architecture enthusiasts to witness a cross-cultural exploration of ideas. As Switzerland and India celebrate 75 years of diplomatic relations, this conversation was a significant milestone for Bengaluru’s design scene, fostering cultural exchange and collaboration in the field of architecture. This was an evening of intellectual discourse as these two architects wove a tapestry of diverse influences that shape the world of architecture.

Dialogue: Peter Zumthor and Bijoy Ramachandran

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Thank you Jonas, Swissnex, and the Swiss Consulate for bringing Peter Zumthor to India. I welcome him and Hannele Grönlund, the Finnish architect and exhibition designer to India and, our home, Bangalore. (claps)

A friend of ours said that this evening’s event felt like the opening night of a big Bollywood blockbuster. Peter’s work and writings find a particular resonance in India. His ideas of work predicated on place, memory, materiality and construction, and presence, a word he uses often, make direct connections to our own traditional buildings and the work of masters like Le Corbusier, Louis Kahn, Charles Correa, and BV Doshi, who are so familiar to us.

The last time I was in this wonderful room was in 2014, with Correa and Jyotindra Jain. It is my privilege to be in conversation with Peter here again, this evening. I was very flattered to be invited and initially thought that this had something to do with the work that I was doing, but now know, after Delhi, that the organisers just wanted Peter to have fewer names to remember. As of this morning, they’re still looking for another Bijoy for the Mumbai chat. I’m just kidding (laughter).

I’m a bit nervous, of course, after having watched Peter in conversation with Juhani Pallasmaa, Tod Williams and of course, my namesake, but I see many of my teachers and friends here this evening, and so Prem (Chandavarkar), Edgar (Demello), (Sanjay) Mohe Sir – I may lob few of his tricky questions your way. I hope you will have my back.

The format for this evening is as follows – Peter and I will chat till he has had enough. Hopefully around 30 to 40 minutes, and then we’ll take a few questions, and I hope your questions will be brief and precise.

I invite Peter to join me.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So your first visit to India, Peter. I just thought we’d start with your impressions.

(to the audience) His itinerary so far – he’s visited Humayun’s Tomb, Chandigarh, the Red Fort, the Crafts Museum, the Devi Art Foundation, and of course, this morning, we went to IIM, Bangalore.

(to Peter Zumthor) So, your first impressions? Density? Messy Vitality? Blurred distinctions? And these wonderful buildings that you visited.

Peter Zumthor:

I had an idea of India as a boy and of course, when I came here nothing was true. It’s all completely different. But I do see these colourful clothes of the women. So this I knew. I expected this. The women have these colours and beautiful dresses and this is the first impression. Then the next was, over the first two days – you are all so friendly! You are warm-hearted friendly people. And I know you haven’t had wars and I would hope for you that you stay peaceful. Then I started to look, to get to know people, and this is always the nicest – to get to know people. You start to discuss things, and so on.

And then, I connected with the work of Le Corbusier. I rediscovered that he is really still the biggest hero of mine. I grew up with him, and I have said this on other occasions – Ronchamp is sort of two hours from Basel, where I grew up, and when I was 19, this was the first time I looked at a building with the idea that there was somebody designing this! Okay? There is a profession called architecture. This made such an impression on me.

And when I came for the first time seeing in real life, your two major buildings up there, the House of Parliament and the Court, I had tears in my eyes for a moment because this is so strong – this presence of this person is so strong, for me. When I look at these buildings, he is there. And I think he was strong and he had clear ideas and he was fighting for them. He was not making any kind of compromises. He invented Land Art because there was too much rubble so he made two walls and put this stuff in. Anyway, this was very strong.

And then some people told me, maybe you should look at the Doshi building and there I heard the name. I have seen some photos and this morning, I discovered the second building I’m passionate about. This is really amazing, what you have here with the School of Management by Doshi. This clear kind of structure but a lightness in doing the whole thing. There’s lightness and elegance. It doesn’t feel like an institution which wants to impress you. So, you are free there. I’m happy I have seen this. Thank you!

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yeah, someone was saying that IIM is a sure bet, that it always lands, you know? So you just have to take people there and it delivers every time.

Peter Zumthor:

It works.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

We were speaking to Mr. Correa’s wife, Monika Correa, and she said that when they were very young, Correa and Monika went to Chandigarh and Corbusier was there. So Corbusier and Monica were walking in the front and Charles and Doshi at the back, were following them. They go up to the top of the Assembly building and Corbusier whispers into Monika’s ear, “Aren’t you proud that you’re married to an architect?” (laughter) The Power of this amazing diagram, you know?

Do you see with the IIM building and your own understanding of Corbusier’s work and possibly Kahn’s work as well, how do you position IIM in that context? I mean, what is different about it? Or is there something that you see that’s unusual or particular of this place?

Peter Zumthor:

I should compare what buildings? Corbusier?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

The Management building that you saw today, Doshi’s buildings, with either the Corbusier buildings or Kahn’s buildings that you may have seen.

Peter Zumthor:

Well, this morning – this was obviously a bit of a combination of Kahn and Corbusier. Two strong figures who worked in that very direct, handmade way. Maybe Corb even more – you can see there were people doing this. You know, you can almost feel the people when you see this– how they were doing form-work. I like this – I love it a lot. And this is a bit more refined as you know. But it’s also a bit thinner – It’s not so…

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Robust, yeah.

Peter Zumthor:

It doesn’t have this robust brutality I like so much. (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

It’s a bit too delicate.

Peter Zumthor:

No, it’s not too delicate – it’s more delicate.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

It’s more delicate.

Peter Zumthor:

Yeah. You know all of this – Why do you ask? (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

It’s too early for that! That’s a little later. Let’s wait for a bit. (laughter)

So, to begin maybe we’ll just talk a bit about your inspirations. The beginning of you finding yourself, in a way. Your father is a cabinet-maker. You worked with him for a few years; went to Pratt and then came back because he didn’t agree to pay for your architecture school. I mean, I’ve read this in the books. And then you worked for the Department for the Preservation of Monuments for a bit, restoring buildings.

Peter Zumthor:

What do you mean a bit? 10 years! (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

10 years, yeah.

So can you tell us a little bit about how you found yourself, in a way? Or how you came to be an architect? When did the lights turn on?

Peter Zumthor:

So, when I was 17 and 18, this was the time when I went for the first time to Ronchamp. I had a secret wish that I would be an architect or a designer. Or a very good jazz player.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

A very good jazz player?

Peter Zumthor:

This was the thing there. But there was my father, and I was the oldest son, so, of course, tradition says you take over the shop, okay. So then, there’s the thing the parent wants, or the father wants and the thing I want. And then, I went off to apprenticeship, which was actually a good thing. I didn’t like it with him, but actually it’s a very good thing. You learn how to do something with your hands. It’s a federal degree we have in Switzerland. It’s an excellent education – I like it. Anyway, then I went to Art School. Art Schools at the time were not yet academic in Austria and in Switzerland, which was a problem for the art school, but it was good anyway. It was modelled after the Bauhaus in Fachklasse (art school) and Vorkurs (preparatory course for art school).

I wanted to go to the Fachklasse, but it turned out to be boring. Before I had to go to learn how to draw and mix colours and all these kinds of things for a goddamn year – I hated it! It was the best I ever did there, you know? It was a really good basic education in drawing and looking, and most of all about looking, okay? I got into this art school with no drawings. How is this possible? They said you have to show the Director some drawings. “Do you have drawings?” I said, “Yeah, sure”. So I had to go to my friend, who went to the gymnasium. He was always good at drawing and I did not have a single drawing. So he erased his name, put mine there. That’s how I got into the Art School, okay. (laughter) But the secretary said, “You can come, but in half a semester you come to me and show me your grades. And then we see whether you can stay or not.“ So it went well. (laughter)

Anyway, so this was this. And then, I asked my professors at the art school, “What should I do?”. These three years, that’s nothing. And then one guy said, “You should go to Jean Prouvé in Paris. This is exactly the person for you. For the things you do Jean Prouvé will be perfect for you.” And then another guy said, “No, you have to go to Pratt. There’s Parsons, and these people – Industrial designers (which was also an interest of mine). You should go to Pratt, New York.” This, you have to see, this was not a time where it was normal that you go to study in America. My mother didn’t believe it. When I told her I’m going to America, she said, “ Hahahaha!”. (laughter)

Anyway, so, I did go to America, I didn’t go to Jean Prouvé. You know why? I always had bad grades in French language. Life, huh? (laughter)

So at Pratt, I discovered interior design. Terrible. (laughter) Then I went to Industrial Design. The guy looked at what I did at Art School and said, “You could make a masters with me. Nobody knows as much as you do already, so, you could do it.” Then I dared to go in the direction of architecture. And this was a big thing of respect. Because I always had a sort of secret wish that I could become an architect. But I had a feeling that this is so complicated and so difficult to become an architect. How wrong I was, right? (laughter)

So I had this great respect. So I started it and then my father came and brought me back again. And people sometimes said it was a big disappointment that your father didn’t pay anymore. And then I have to be honest right? In life you have to be honest. So I say no – because it took the pressure off me to become an architect. So I went back, and at home all of it was political. So for ten years none of us in the German part of Switzerland, who had a little bit of something in his head, was not political. Maybe you heard about that. So, for 10 years, you could not do Gestaltung as we called it. So, I went to this preservation of old buildings, making inventories, studying these things, because nobody wanted to go there.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Right.

Peter Zumthor:

And I liked to go there, in this beautiful Canton. So I worked there, and everyday I thought, “Hey, this is like vacation and they pay me!” (laughter) No, this was wonderful, and I learned a lot about villages and structures and things. Because design was politically not correct then – hard to believe, but that was the 60s. It was not correct to work on Gestaltung. And I’m still not yet an architect.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Still not.

Peter Zumthor:

So in 1979, it became possible again to study to become an architect. And that’s what I did.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

And this was in Switzerland that you studied?

Peter Zumthor:

That’s where I lived, in this small hamlet. In Switzerland, everybody can participate in architectural competitions, can apply for architectural competitions. So I went with a colleague, an architect who had studied at ETH and looked at the entries of a competition. He didn’t win. And I saw the first prize, and then I went home and told my wife, “I can do this better.” (laughter)

And then I started to make my first competition and they kicked me out in the first round. And in the second one, I was already winning. I had to change something in my attitude towards things. There was a little bit too much site – conservation things like, you should copy things, and so on. And when I saw the first prize in the competition I lost, then all of a sudden the old air of the art school came back – the pioneering tradition of Modernism.

And then I did my first buildings. I won a competition, did three buildings. There was a moment when I went with my wife to look at these three buildings. They were not even yet finished. We looked at them and criticised them. And we felt depressed as hell. Because, I said, “Look at this. This is too heavy.” And from then I decide, this is not going to happen to me again. From now on I do my thing. So there’s a publication at the ETH titled “Zumthor before Zumthor”. (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I couldn’t find those three projects in your monographs. I’m gonna dig for them now. (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

Good Luck (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

But were you looking at other architects at all? I mean, were there early influences, or people’s work that you were fond of or who influenced you in some way? Maybe not just architects but writers or thinkers or artists?

Peter Zumthor:

So in the late 70s, beginning of the 80s, all of a sudden there was a young group of Swiss architects, who worked completely differently. So we also had our own publication. We took this over more or less. One of our guys became the editor.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

This is Archithese?

Peter Zumthor:

Archithese, yeah. We started discussions, theoretical discussions together and looked at each others work. It was a very exciting time. And there were these official Swiss Association of Architects Publications. We did not look at them, okay? They published these huge buildings pretty well or very well. But we published the bathroom this one guy had sort of restored for his aunt. This was something really intelligent so we discussed this. Herzog & de Meuron, they were in this group.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Ah, they were in the group as well?

Peter Zumthor:

Yeah, we were five, six, seven of us. There was Roger Diener, maybe you know? This was an exciting time! I didn’t feel competition. We were not really becoming friends, (laughter) but it was a good time. We were talking about the same things, we made exhibitions, shows and so on. We had theoreticians like Martin Steinmann, so this was a great time. And so that’s how we departed, and till today we can talk.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yeah, we always see that with architects. That there are usually these, what Brian Eno used to call the Scenius – many people together and then this kind of critical energy.

Peter Zumthor:

That was a great moment.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I’m gonna segue to the questions I had about process. So the first is about beginnings. In your writings and the monograph, many of the projects seem to come, somehow, in some sort of a dreamscape – that you’re working on things and then you come, you arrive at an idea, and it is a bit mysterious as a process. How do you get to a place where you think, “Okay, you know, this is a great idea. This is something that we should pursue.”

So I wanted to ask you about the beginnings of things and how you come to, how do you react to a project. Or how do you start?

Peter Zumthor:

I think it’s a good question. Thank you. I think first I have to say that in my case it’s like in your case. We all know this. We have to start, we need an idea. Then all of a sudden, there is an idea. Okay I could ask you. You, (pointing to Bijoy Ramachandran) how do you find your good ideas?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Well, there is a big difference. There’s a big difference because I don’t end up where you end up. (applause and laughter) We may start at the same place but… I’m thinking maybe you have a special, you know, tonic or something that you’re having. (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

I take drugs! (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Okay. (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

Okay, looking at how I work, how it happens, I would have to say I like this moment of the beginning. I love it. Nothing is yet clear so I can go and ask the client, “What do you want? What do you want to have built?” I like to be an architect who has to fulfill, answer to the use. So I go and ask. Not to just slavishly follow everything, but just to understand. I go to the place. But maybe I don’t go to the place; I pretend I have been there, but I haven’t. (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So it’s not essential?

Peter Zumthor:

I’m not putting up a tent on the site. This, I’m not doing. I always think it must be enough, what I have inside me. My knowledge of here and there. And all of a sudden there’s a spark. And then I think, “Huh, could be good,” and then a long journey starts. So this goes up and down and up…Everybody knows this. All architects I saw before, we all know this.

As you know, I trust my intuition. So the way I use my brain to check on where my intuition leads me to. So this is good. I say, “Listen guys, what are we all doing here? Does this all make sense?” And then you start a discussion, with a friend or so. We start to see – does it make sense?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Is it a personal thing or are you with a group and trying to come to something together? Or is it you, just trying to work on it and come to some … I mean, those beginnings, are they shared or are they private or intimate?

Peter Zumthor:

As soon as I have a good idea, I look for somebody to share it with. Of course, they have to say, “This is fantastic!” (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

That’s essential in the portfolio to apply for a job, yeah? “I will agree with everything” (laughter).

I met Glenn Murcutt once, years ago, and we visited the Boyd Center which is a beautiful building in Shoalhaven, outside Sydney. So when you first meet him, you think that he’s going to take you around the building and talk about the poetics of it, and you know, this wonderful aesthetic kind of explanation. And then the whole time Murcutt was walking us around he spoke about construction, about managing the water and dealing with the fires. And we’re like, “Okay, so…”

And so in many of the ways that you describe your work, you are also coming at it in a very pragmatic way – as a way of finding efficient ways in which to do things. Is that true? Would you say that that’s true? And somehow you come to the poetry through this rigorous pragmatic approach?

Peter Zumthor:

The buildings have to work. They have to perform. They have to hold up. And they have a construction and they are made from materials. This I like. So I try to be essential to these things, to understand. I have a great adoration of construction, structure, and all these things. So I try to get these things right in terms of this vision – of the spark of Saturday morning, right? This can take half a year, or two or three years to get there, and it gets more complex as you go, and you have to integrate more things. And, yes, in my office, we talk only about this. This seems to be a common understanding even without talking about it. We are not at a university making high-flying thoughts and poetry. We just have the real things to do. And if we’re lucky, you know, maybe there’s a trace of poetry later. But, yeah, that’s how it is. I like this. I love it. I like to make anatomical models of the construction, and so on.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

There’s a great description in one of your essays about the Thermal Baths in Vals, where your first sketches are monumental. They are the rock itself and the pools of water in the rock. And then of course you go to the quarry and you can’t find massive pieces of stone that then you can use. And so you have to now invent a way to do that. And then you come to doing the slices of stone. All of us know the story. Then at the end, you achieve that dream, you know, the vision of that original idea. And it reminds me of Kahn’s idea of the immeasurable, measurable and then immeasurable. So, the question really is about when the material comes into play. I mean, initially, are the ideas incredibly vague or is the material often the beginning of things? That somehow the place, the material becomes the root of the idea, of this spark.

Peter Zumthor:

Yeah, the first image usually is not abstract, but very central. It has already a material somehow. So, I cannot remember that there was an abstract idea of something. Maybe, you know, there’s this very early building of the Roman ruins?

So there, was an idea – I want to make a shell around these things to show, like, if the houses would still be inside, right? So you have the Roman urbanism there, this little piece you would see. And I think the material came second. This is the stone foundation. And then I asked somebody, “Did the Romans always use stone? Or did they also use wood?” And then soon I said, “The farmers living here – I think they just had wood. Let’s do wood.” So there maybe the wood came second. But it was very soon. And you know why right? Because it makes the space. It makes the atmosphere.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yeah, the ruin – the enclosure of the ruin. Actually, among some of the projects, there are these cousins. They are related in some way. I feel that Kolumba is somehow related to this Roman ruin enclosure, that somehow Kolumba also makes the edge, instead of separating and making a distinction, you actually embrace the enclosure that is made by the old ruin. There’s this link maybe, I don’t know – I’m reading into it, but I feel like maybe there is.

Peter Zumthor:

No, so, this was still the time when I don’t know here, but in Europe, the architects learned or they were taught that if you have an old building, take it away. And if you have to keep it, make a big contrast. So, you would always see this massive building, and then glass and steel and all these things. And I found this very boring. These ten years of working on monuments and sites have taught me that. So I was always thinking along the lines of making a “new whole” of the whole thing. So “embracing” is a nice word, thank you.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So that’s beginnings. Of course, I hope we have questions later about that. The second one was about memory and emotion. I told you this at the Institute in the morning. When (François) Truffaut the famous French director went to America to meet (Alfred) Hitchcock, he made these little films because he was a big fan of Alfred Hitchcock. And there’s this one portion in that book which really reminded me of some of the things that you write about. And Hitchcock says, (paraphrasing) “You know, what I’m after is pure emotion. I’m not really interested in narrative, and acting, and message, or politics. All of those are okay. I am interested to get the pure emotion out. So if I’m in the theatre and there’s something happening on the screen, it has to connect viscerally, immediately, without this whole layer of theory, and whatever else.”

And so I wanted to ask you about that, you know. So, when you are working, you’re looking at what the emotional quality of the building is. You’re making models, very large models. You’re trying to figure out what it is to inhabit that space and get a certain sense. The question is, how do you think when you build it – Is there something that’s different about the built condition versus what you have envisaged in the design process? Is there a gap or is there something that improves or changes in that translation from what you’re doing in the office to what is being built?

Peter Zumthor:

First of all, I think I agree completely with Hitchcock. Do you want to listen to a Mozart String Quartet and somebody explains to you why this is good or bad? I mean, this is an emotion – you listen to the music and then it gets to you, or not. And I think, for me, this is the same with architecture, or with art, I mean, there are artists who say as soon as an art historian, sorry there may be art historians here, starts to talk about art, something is covered of the art. It’s not there anymore. You cannot see it anymore. So this is not against art historians; this is more a plaidoyer for immediate experience. We should allow for this and I think this is also the proof of good architecture. If I go this morning there, I come into Doshi’s building and it’s there! Puff! It’s right there. After two seconds you see what this is. Yes, I’m going there.

The second is, does the reality fulfill the anticipation? (pauses)

My grandchildren know I have only made one building which is not so good. I don’t like it. What I am saying is, usually, they surprise me to be much better than I thought. Sorry to say, but that’s the truth.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Really?

Peter Zumthor:

I think the reality is if you would work very long on something, and you imagine this and this, and you are very careful. If I feel something is not good, I annoy my client by saying we have to change something. Going through all of this, my experience is – better than I thought.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Oh, really?

Peter Zumthor:

Yeah. Sounds a bit conceited, but that’s how it is. Now he doesn’t believe me. (pointing to Bijoy Ramachandran) (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I have to visit so I’m hoping Swissnex will now take me to Switzerland to see your buildings. (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

You heard this? (gestures to the organisers in the audience)

For me, an Embassy somewhere, and for him a trip to Switzerland! (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So, just to push you a bit on that process question, how do you test this emotional quality in the studio? What kind of strategies do you use?

Peter Zumthor:

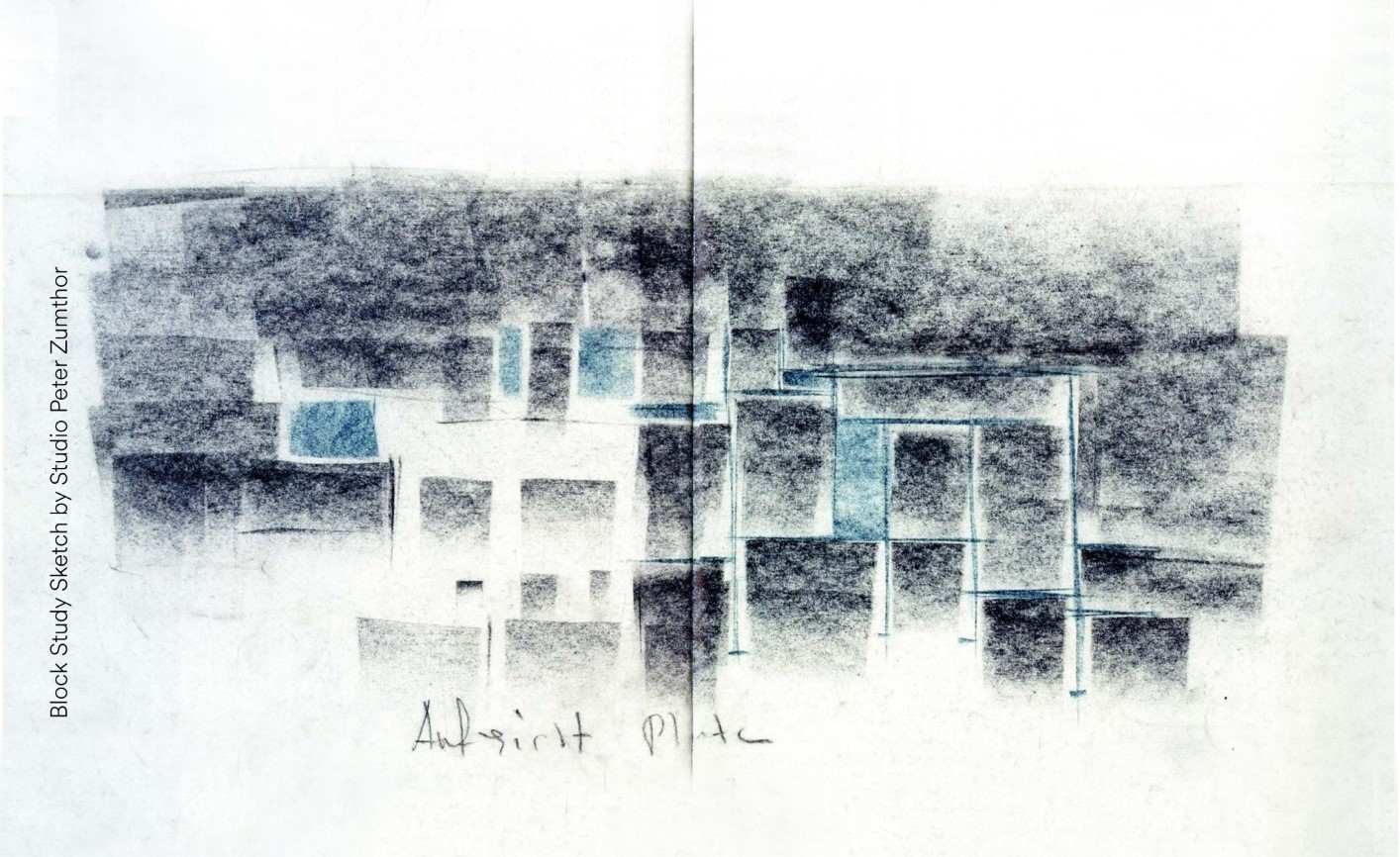

It used to be drawings, pencil drawings, many pencil drawings. You see, this used to be the time when on Saturday mornings, I had the time to really be myself and try out things. And then it changed when computers came. This I saw, afterwards – the more the computer drawing entered the atelier, the more we started to build models.

And now I have hundreds of models. I think it’s 2000 sq. m. of models in all of the phases. And not all of them, but many of them are very good, like, on their own. But I think you can always feel that they don’t want to be something for the art museum or something, they are all going in a direction and so, the model helps a lot. And I don’t have any more this chance, when you do small buildings, that you can go to the building itself, you know. But if you do bigger buildings, and you go and look at the building and say you want to change something they kill you! (laughter) So you have to get all the decisions before. Models and trusting my emotions. This goes like this – I say, “Now we have it, let’s do it!”. The client says, “Great, fine. He has it, okay,” (laughter)

And then all of a sudden I realise I have a bad feeling. And this increases. Then I start to take this seriously. I thought this is so beautiful already and now, this comes and I don’t know where this comes from. It’s inside me that something tells me there’s something wrong, and then I go there again, for the third or fifteenth time. We go there again and again. And then you have to be very patient. My people in the atelier, also have to be … and so on.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Is there a project that went through this kind of really fundamental change midway? That you had a bad feeling and you had to change? Can you remember?

Peter Zumthor:

The general idea, the spark, never changed, okay? But like in Los Angeles, I remember, I was almost finished with the project. We showed it to the public…

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Which project?

Peter Zumthor:

In Los Angeles, this museum, which had the idea that we are collaborating art with the natural museum on the other side because my Director (Michael) Govan said art and natural science should be together, they should communicate. Not a bad idea, I guess. But on the institutional level, the natural science people said, no, we are doing this, you do this. Like it is in life, okay? So I had to make a new project, crossing Wilshire (Boulevard) and so on. But that’s not a change which came from me.

Observation – if it’s a cultural area which I know well, it’s quicker. If it’s a cultural area I have to go through a longer trial and error phase until I think, “Now it fits.” Now I will never get a commission in India. (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Well, you know some good architects in India now. (laughter) We can help.

Peter Zumthor:

What do you mean exactly? (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

That’s awful! Ouch! (laughter)

The third thing about process, Peter. I wanted to talk about, and this is my favourite. There’s a wonderful book that all of you should get. It’s a conversation between Peter and Mari Lending, about the Zinc Mining Museum. And it’s just the most incredible conversation. So this is the question about time.

There’s this wonderful story about the miner and his wife, you know. They’re a young couple. And the miner who’s dressed in black, and the author (Johann Peter) Hebel says “dressed for death” in a way – it’s really bleak, just married, goes into the mine, and of course, he doesn’t come back.

Peter Zumthor:

Now he tells you the story I want to tell you. (laughter) No, you can say it – it’s a beautiful story.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yeah, but thanks to your book. So anyway, then years later, they are able to retrieve the body of the miner and it is immaculately preserved. And the wife who has aged is now confronted with the past, viscerally, immediately. And in some sense, I mean, what Mari is trying to make is the connection back to Peter’s work and to all these buildings that somehow make time travel possible, you know? That it brings back some kind of primordial memory. Again, I hope someday to visit these buildings to feel that. It is incredible. I get goosebumps with this story.

What is it about time? What is your preoccupation with time and this idea of memory? And the building of things that help people make this passage?

Peter Zumthor:

Okay, I’ll answer your question. But by the way, I told Mari Lending this story, not she me, okay? (laughter) It’s an old story. I was always impressed by Peter Hebel.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

He’s a Swiss-German writer, you said?

Peter Zumthor:

On the border of Basel. We don’t know. (laughter) Left or right. Okay, my relationship to time.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yes.

Peter Zumthor:

(pauses) I guess I’m proud to do buildings which will get older than I do. If I look at this now and you ask me, I’ll say, yeah, pretty cool. If they’re good, they will be there and they will be used by people who don’t know me and so that’s a nice idea. It’s also that you can make the building become part of a human landscape or whatever – of where we are, where we live. I think that gives me a very good feeling – to do something like this. So that’s one. But do you mean something else?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

My question is, you say this in one of the essays, that when you are trying to make, doing a building, you’re trying to evoke memories that are not personal so much, but about a sort of primordial memory. A sort of ancient memory that maybe we share. That there is something cultural, like that, that you’re after.

Peter Zumthor:

I think we all have our biography. We have seen a lot of things and experienced things and most of the things are not intellectual things. They unconsciously make our biography we live with. And so when I build something, I use this as a big source of inspiration. Most of all, I trust it. I would trust it much more than any intellectual theory of architecture or concept. As a theory, I like architectural concepts, but theoretical explanations might not do the trick for me to root my building. So my buildings, I want them to be rooted and I hope they are rooted in our biographies. Not only mine but also yours and everybody’s. And I think that this is again a very noble task of architecture, to have this quality. Am I being clear?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

You think buildings can transcend boundaries, can transcend locality, can transcend culture? That all of us will have similar experiences in the great buildings? Do you think that that’s true? So you may be after that, I guess.

Peter Zumthor:

It’s there. I know it is there. Yeah.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I also like the wonderful comparison you make between factual and actual facts.

Peter Zumthor:

Did I? (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yes.

Peter Zumthor:

When was that?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

It’s also in the book! (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

Oh, okay.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

And this is when you’re talking about the preservation, when you were working in the (department of) preservation, Mari says that she loves drawings, she loves all these things. And then you say, there’s factual stuff – the history that’s written down, that is transferred. But there’s also the actual fact– what you experience when you are there, it resonates and gives you certain information.

Peter Zumthor:

So, I discovered something I always knew, that everybody knows, that history is stored and preserved in material things. So I learned if, my daughter-in-law is a historian and a lot of my friends are, so if you study history, I watch them reading papers, and then they write a new paper and they quote other papers. So from paper to paper to paper to paper to paper to paper… that’s then history. Okay, but I’m interested in factual history which is stored in objects and places. And to be part of that or to become part of that, I think, has another dimension than the history on paper. Do you know what I mean?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yes, yes. Wonderful, yes.

Peter Zumthor:

Nice profession to be an architect. (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I understand what you’re saying but I have no clue how to put it into practice. (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

You’re too modest! (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So here’s just reflecting on my own practice, I wonder if you’re ever, you know, plagued with doubt, that you’re sort of in the dark. Inspiration isn’t coming you know. There’s nothing. There is no spark. You’re spending days on the table but nothing’s coming. I mean, does that ever happen to you, or…

Peter Zumthor:

I have no problem with inspiration. (laughter)

So, it’s not my thing. I did nothing, it’s just the way I am. So, if I have too many troubles or sorrows or something in the profession, I can feel that I’m not free anymore and it’s more difficult to encounter my good old self, Saturday morning self, you know? Where the ideas just come. But they are always there.

But as you know, the building is taking place in structures. And the structure of the client, the structure of the general contractor, the structure of the bureaucrats, you call them, and so on and so on. There are many, many layers of structure, as an architect I have to deal with and sometimes they’re not in favour of me or they might even dislike me because I disturb a process. And the building trade gets more and more divided into processing like doing a car. So the designer makes the design of the car, and once this is approved, he is not going to change anything, right? And so he is at the beginning of a process. And me as an architect, I want to be always there. In the whole process. I know maybe sometimes it is not possible. And so, I have to study the structure of the building I’m doing, and there I need allies and friends. And if I don’t have them I should not even start. Because it’s so difficult to do these things then.

The other thing is the doubts. I have them a lot, okay? And this is the moment when I feel there’s something wrong and I don’t know what it is. That’s all. No, the doubt – it’s something like that. This is always there, isn’t it? I think most of you know this. In normal life, you never know exactly – is this good, is this not good, okay?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

There was a question that a friend of mine asked me. You know, that your work, it’s very slow-paced. You take your time. You really investigate what you’re doing. When do you know that you’ve reached some kind of a chrysalis? That you know it has come to a shape that it’s really amazing and that I don’t have to keep working on it any more. That it’s done. It’s reached. How do you know that? When do you know that?

Peter Zumthor:

To the first part of your question, me and my team, we are not slow. (laughter) We are pretty damn fast. But things happen. They block you, or you don’t know. And then, you know, if I feel something is not right, I go there. If I would have to do something and anybody in the huge structure of the building tells me, “Forget it, we don’t have time anymore. We don’t have money for this”, I don’t give up! That takes time. Not giving up, that takes a lot of time! (applause)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

The next question is about experience, Peter. And the question was, you know Berger, John Berger, has this opening line in The Ways of Seeing, he says, “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognises before it can speak.” So do words come in the way of experience? Is it possible to see the world without intellect, in a way? Without labels, without words? I mean, do you think that that’s true? That we’re trying to come to a place where we’re not looking for words to explain, but trying to see like a child.

Peter Zumthor:

I think the basic things in the world, I would like to see like a child, or like to see in a direct way, an essential, normal, everyday way. I like philosophy. I like to exchange arguments and such, but life, actually should be grounded. I’m not looking for the truth by working on words. That’s why, maybe, I became not-a-philosopher, but an architect. So yeah, I like that. I’m not against thinking. My feeling is the emotions, they encompass huge fields of everything. We have experiences. So emotions are big. And to me, the intellect and thinking, it’s like a laser line. So you can look at this, then at this and then at this. Very small. Very small. But emotions are like this (gestures vastness). So at the end, for me, emotions.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So why did you write the two books? What prompted you to write Thinking Architecture and Atmospheres? What propelled you? Did you feel the need to put down, a way to articulate what you were trying to do?

Peter Zumthor:

Thinking Architecture started when I was invited to help teach at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles. And then, as you know, they want a lecture from you. I took this task to say for the first time, then I had the practice for twelve-fifteen years already, to look back and say okay, what are the things, what am I doing? So what are the things which interest me? Then I locked myself in for ten days, three packets of Camel every day. Day and night and I had all these bits and pieces of, fragments of ideas hanging in my barrack there. And then I tried to put this together in English, sort of what is my interest?

This was almost the last or the second-last week of the semester when I was there; Then I had this lecture, okay? And from then on, all the students wanted to come to me, but I had to go home. (laughter) Before, nobody was much interested, because nobody knew my name or whatever. That’s okay, but it was a great experience. So that’s how it started. And this is called the perception of things, So what is it? And this kept on, you know? Every two-three years, I took the liberty to think again about something. You know it…

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Is it useful, do you think, to do that as an exercise? To write or to articulate in that way about what it is that you’re doing? In a way to explain to yourself maybe, I don’t know?

Peter Zumthor:

This was the laser okay? But I like to write. So this helps. I like to write– it’s not, for me, a problem to write. So I like to put this in words, and write it in a way that the feeling stays as big as possible and it makes things clear to me, okay?

It’s like the door handle, this door handle of Le Corbusier, you know. I made this door handle recently, a niche with a pole. And when I was in Chandigarh I see Le Corbusier copied me! So, I must have seen this detail of the door handle twenty-thirty years ago but I would not have been able … although now it’s a feeling, I must have seen this, but I was sure I invented it. (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I think we’re kind of running out of time.

Peter Zumthor:

Oh, good! (laughter)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

So I thought we could end maybe with a message, or you know, some suggestions. There’s a fairly sizable number of very young architects in the room, a lot of students. Anything you’d like to share about your own journey, or lessons from time in architecture with the youngsters in the room?

Peter Zumthor:

Yeah, I find it extremely difficult to give advice, to young or old or any architects. I mean, what should I say? (laughs)

Some years ago I told the students, “You know what? When you design a house or build a house, you should always do this like it would be for your mother.” Meaning, this has to be normal; It should fulfill the needs, somebody should love it, mothers always love what their sons are doing, that’s clear. (laughter) Anyway, all of these things, okay? So, this is a stupid answer – be yourself, all these cliches. Be yourself! (laughter & applause)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

That reminded me of a story, a Doshi story. When he was sitting outside the classroom and some students came out of the classroom from the college. And so Doshi asked them, “So what did you learn today?”. They said, “You know, we had theory class today and we learnt about contrast and all of this stuff”. So Doshi listens and said, “Now you go home, and explain all of this to your mum.” See how that goes.

So I think we’ll open for a few questions, is that’s okay, Peter?

Peter Zumthor:

Sure.

© Parikshith Kalkai

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Yeah. Edgar, do you wanna go first? We made a deal, yes. (laughter)

Edgar Demello:

Wonderful conversation. So, I’m just trying to now figure out what has been left out that I need to ask. But, I would like to ask Professor Zumthor about one building that I have visited, many years ago, maybe twenty years ago, because it intrigued me very much. It was the KUB or the Cube in Bregenz, the Kunsthaus. And there was so much in that building that, to me, in its physical sense, not the metaphysical sense, didn’t really accept the lake. My reading of it. And I saw the drawing recently, maybe five days ago, of that elevation and to me it seemed it was an elevation drawn by a monk. One hundred and eighty, I counted now, rectangles, three of them removed for an entrance. Now, what you ask the lake to me it seemed, “I’m not asking much from you except your light, so that it can soak my glass panels.” Now, I want to ask you, how did you take such a heroic position of, what’s the word, restraint? How did you take such restraint in this project, where you had four sides, all frosted glass. Not worrying about– the lake is there, you have your own little plaza at the back. How did you come about that? And of course I realised this wonderful thing that Mies (van der Rohe) said but he didn’t put it the same way, “Liebe Gott steckt im Detail”, and that for me was actually the building. More of course than is experiential.

Peter Zumthor:

Not making any window outside is more than a detail, But did you like the whole, did you like the building? (laughter)

Edgar Demello:

No, I actually loved the building. And I was hoping one day you would explain it to me. But I have to say one more thing, it was a double question, the opening apparently was an exhibition of James Turrell. How could Turrell add anything to that magic lantern that you put on the lake? Now you know I like the building.

Peter Zumthor:

Okay. James couldn’t add anything. (laughter) It was interesting what he did. He put some artificial lights into the facade and inside he had some of his early skyscapes (skyspaces) and they were beautiful. They were good for the building, but he couldn’t add to the building. But I don’t want to be arrogant. At those times, when we designed, when there was the competition of the Kunsthaus Bregenz, the white cube was a big thing, right. So all European architects said there has to be a white cube. Its a modernistic idea. We all know in the meantime and before, that art always has been on materials, wood or things, and not on a white surface. A lot of paintings hate white, okay? If you look at it, they would look much better on a colour or something. The world is going back to this kind of thing.

And there I said, I want to have a building which has a certain presence, which doesn’t duck away to be a white box, which can be made of cardboard and white paint. I am an architect. I think a good building should have its own presence, in its own way, but very simple. And then I wanted to bring the daylight in, okay? So in the competition, I brought the daylight in with big openings which should reflect sunlight like this and then in, and then this. (gestures) This was the competition. And everybody more or less believed in it, that this could work. It didn’t, okay?

So, this is an anecdote, but a really nice one, okay? It has to do with this light in the facade. So, for a long time, we didn’t know what to do with the facade. But, the rest inside we had figured out. And then, somebody recommended me an old man from Stuttgart who was a specialist in daylight. He was seventy, a very delicate man, you know. Then he came on the train to my village. Then he came there and then there was a big blue sky. We are in this mountain region where the sky is blue and the sun is there, so its really just great, okay? So, he comes there, and he sees the rock in the light and the blue and then he says, “Zumthor, could I please first take a walk for an hour? It’s so beautiful!” So he went out and walked around in the village, and after an hour he came, and then there was an interesting discussion. Then I learned from him, that if you have a frosted surface, I’m sure we all know this, the light comes from there, or from there or from there, and then on the inside, it goes in all directions, okay? And this was it. And then he lowered the vertical shades at my atelier, the old atelier, and he said, “Look, I’ll show you something.” So the sun was there, and he lowered these textile shades, and the light came in. And in this stupid kind of contraption we made of this to this (for the competition), nothing came in. Even less. (laughter) That’s what I learnt there.

And then I only have another anecdote, then I stop okay? One hurdle, because the government of, this is Austria, Vorarlberg, they said we want a window looking, at least one window, looking to the sea. And the best would be on the top floor. A big, nice window so people can look at the beloved port and sea, okay. I said no, doesn’t work, because a window is too strong. It will kill the art nearby. What can a window looking to a lake – I mean, you can paint whatever you want? And I think I’m a bit right. Anyway, so, they called me and said, “The ministers of the County of Vorarlberg have decided there should be a window, Herr, Mr. Architect.” (laughter) Then I said, “Yeah, but you know, it doesn’t help in your design. I cannot make it.” And somehow after a while they respected this. And now its completely – It’s full of light right? Full of daylight, you know.

Edgar Demello:

But in Kolumba you put a window looking at the Dome.

Peter Zumthor:

No, there was this Catholic Bishop, you know. (laughter) He paid for everything.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

There’s a question in the middle, here.

Peter Zumthor:

Yeah?

Sathya Prakash Varanashi:

Yeah, my name is Sathya. I have read both your books – Thinking Architecture as well as Atmospheres. I think Atmospheres I’ve read three times or so. I really liked your magical words, the way you spoke just now, and the way you’ve written. But I didn’t know you’re so popular in Bangalore! This is the largest single crowd of architects I’m seeing in the recent time in Bangalore. Congratulations. But you know in the 90s, and a lot of people like you wrote, or Pallasmaa’s books, or Alain de Botton. They all made people re-look at the way architecture was then emerging. Of course Bijoy used some very, very interesting words. You also used them. And I think your books and Pallasmaa, and Alain de Botton have influenced a generation of architects. Of course, 30 year old story. Now architecture is emerging and reemerging and reemerging. Do you see people coming with books or thoughts or theories today, which is making us re-look at architecture today? Making all of us to rethink about what is happening today? Can you recollect some books or people or projects?

Peter Zumthor:

I have to understand, can you tell me more? Am I able to…?

Bijoy Ramachandran:

He’s wondering if there are any new books or projects or things that you think are doing what you did when you wrote these books that have had- that will have influence? That you think are meaningful and useful and valid.

Peter Zumthor:

You know, I don’t know. Really, I don’t know, because I am working and I don’t read. I don’t look at magazines; I don’t read books. But let’s hope so, that somewhere there are great architects. Let’s hope so, okay. And this comes to our knowledge and this will help us. Sure.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

He’s asking you to write a book, Sathya! (laughter)

Peter Zumthor:

Yup! What about you? Yeah, true.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

I think we have time for one last…

Alfonso Tagliaferri:

Good Evening! Sorry, I’m not an architect, I hope I’m not stealing the architects’ spot for the last question. I’m a layman, a bureaucrat if you want. I would like to ask you a question about beauty in architecture. Starting from a simple observation of a layman, who likes beautiful things. And I tend to believe that most of what we have built in the last 50 years, more or less around the world, is generally not beautiful, is generally ugly. I’m not talking about…

Bijoy Ramachandran:

In a room full of architects? That’s fantastic. (laughter)

Alfonso Tagliaferri:

No, no, this is part of the question. If you exclude public buildings, museums, institutions, Kunsthalles, theatres, but if you talk about middle-class housing, you see that usually what is being destroyed was prettier than what is built. Even though, history has never churned out so many architects like today. And I wonder why is this possible. I mean, I understand the pressure from the economic players, the need for more density in habitation. Okay. But if you look for example at Bangalore, I’m not from Bangalore, but people here always tell you, if they’re more than fifty years old, they tell you, “Oh, Bangalore was so nice forty years ago; Was so nice fifty years ago.” And still, they’re knocking down bungalows to do high-rises. I understand the pressure from population but this is going to increase and increase in the years to come. So, this comes to the question, what can be done to break this vicious circle? What could the policymakers do to conciliate (sic) the need for more housing, more density, a little bit of cost efficiency, but also beauty for the eyes? Because otherwise the future is doomed. Thank you. Sorry, everybody. (applause)

Peter Zumthor:

I agree with you. I think everybody in here, I think, agrees with you. It seems we have become more and more, in modern society, more and more difficult to make beautiful or even dignified houses. Simple houses which offer a certain dignity. This has become difficult, okay? And this is not the architects. The architects, I think most of them are still trained to be artistic geniuses. But when they come out of the university, they come into the field, where architecture happens, as you said, into the world of business and economy. There you have to perform as an architect and that’s not easy, you know. Somebody says this is too expensive, and you say but this is more beautiful. Then this person will say, “Yeah, beauty, this is something subjective.” That’s it. So it has become more difficult. More difficult. And this would be another long discussion. Why has it become more difficult? I have some ideas, but I think, I cannot wait so long to have my drink. (laughter)

This may be worthy of a longer discussion. What can we do? Not so easy. We cannot just say the capitalist- These evil guys, get them out then everything becomes better. We know it’s not like that. Russia has not been better. Eastern Germany was not nice architecture. Anyway, big discussion, yeah. That’s the next one you can organise! (points to BR)

Bijoy Ramachandran:

In Switzerland!

Peter Zumthor:

Okay. You mean there are enough banks to help us there? Okay. This is the question which is in the space always, nowadays, you know? We don’t have our building traditions and so on. The king sometimes also had good taste. I mean, he tortured other people but he had good taste. No, let’s not go there; let’s not go there.

Bijoy Ramachandran:

Thank you, Peter. Thank you so much for this wonderful opportunity! (applause)

Peter Zumthor:

Thank you.

Jonas Brunschwig:

Peter, I can’t offer you an Embassy, but, I think we can do something better! We can help you launch a start-up in India! (laughter) Working with the finest craftsmen and women of the country, to build something of cultural and social relevance.

Peter Zumthor:

Thank you. I’ll take your word. I needed to be 80 years of age to make a start-up. Okay! (laughter)

Jonas Brunschwig:

One more round of applause, also for Bijoy, who has been wonderful.

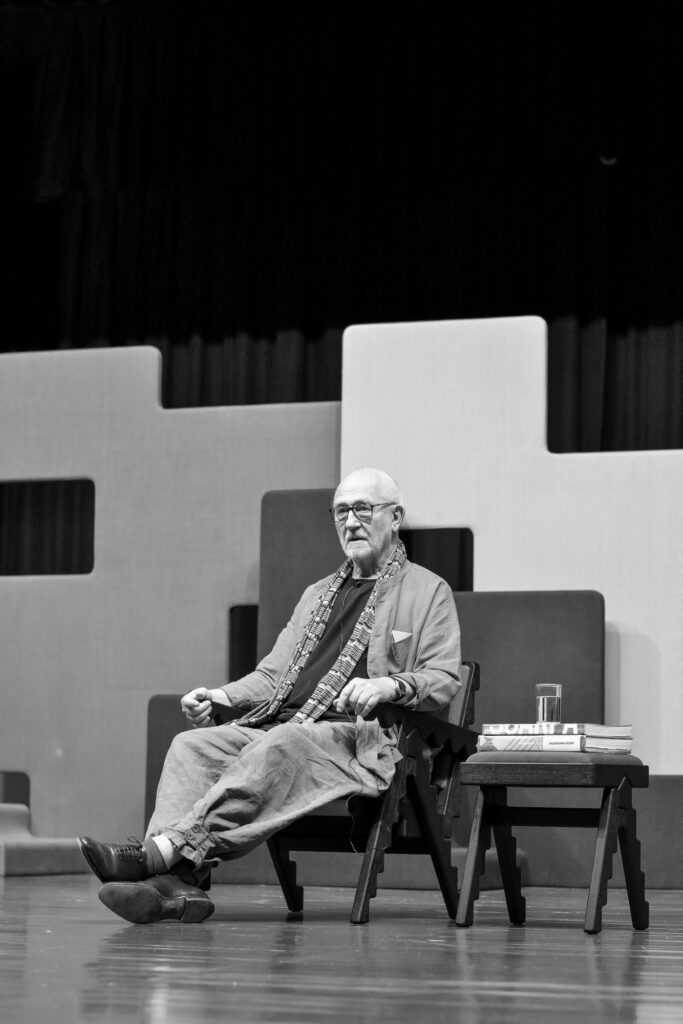

Peter Zumthor

Trained as a cabinet maker at the shop of his father Oscar Zumthor, and as designer and architect at the Kunstgewerbeschule Basel, Vorkurs and Fachklasse, as well as at the Pratt Institute, New York, Peter Zumthor was born in 1943 in Basel. He was employed as a building and planning consultant with the Department for the Preservation of Monuments, Canton of Graubünden, Switzerland. In 1978, he established his own architectural practice in Haldenstein, Switzerland. He was also a visiting professor at the Southern California Institute of Architecture, SCI-ARC, Los Angeles; at the Polytechnic Institute Munich; and at the Graduate School of Design, GSD, Harvard University. He was also a professor at the Academy of Architecture and the University of Lugano, Mendrisio.

Bijoy Ramachandran

Bijoy Ramachandran is an architect and urban designer based in Bengaluru. He is currently a partner at Hundredhands, a studio he founded in 2003 with Sunitha Kondur. Bijoy has a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from BMS College of Architecture and a Master’s degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, USA. He has also attended the Glenn Murcutt Masterclass. Bijoy is currently the Design Chair in the Department of Architecture, BMS College of Architecture, Bengaluru and serves on the Board of Reviewers of SEED, Kochi and the Board of Studies of the Balwant Sheth School of Architecture, Mumbai. Apart from architecture, he has also made two films on the Indian architect B.V. Doshi, both directed by Premjit Ramachandran. These films have been screened nationally and internationally.

Credits:

Jonas Brunschwig, Saraja Cornelia Gantner and team (Swissnex)

Ruturaj Parikh & team (Matter)

Parkishith Kalkai, Lavannya K., Ankitha P., Aishwarya Sridharan, and Swarnavalli N. (Hundredhands)

R. Kiran Kumar (WCFA)

Kukke Subramanya (Kukke Architects & WCFA)

A. Srivathsan (CEPT)

Transcribed by Aishwarya Sridharan